Tech-Nomading from Shore to Ship – Make: Magazine

This is one of my all-time favorite bits of media coverage, and not just because I love Make: magazine (both print and blog). The author of this piece, Howard Wen, really nailed the essence of my technomadic projects… including the wince-inducing irony of their tendency to explode fractally into a level of complexity greater than that which inspired their launch. He pulled no punches about any of that, yet the article feels warm and thoughtful.

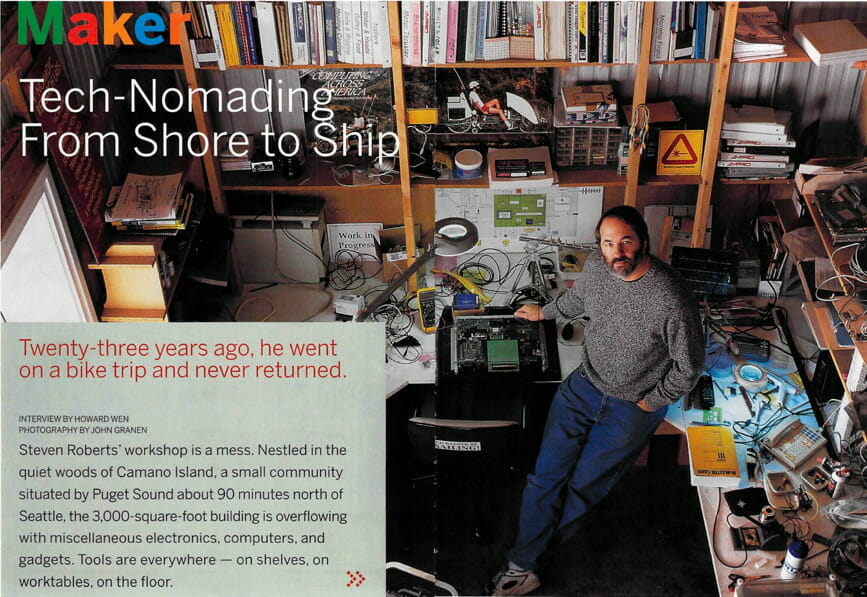

In addition to quality writing, the photos are first-rate as well; John Granen is one of those photographers who taught me technique in the process of shooting an assignment. Getting good lighting in my lab is no mean feat, and he nailed it. The combination of publisher, writer, and photographer really hit a sweet spot…

Interview by Howard Wen

Make: Vol 06 – May 8, 2006

Photography by John Granen

Steven Roberts’ workshop is a mess. Nestled in the quiet woods of Camano Island, a small community situated by Puget Sound about 90 minutes north of Seattle, the 3,000-square-foot building is overflowing with miscellaneous electronics, computers, and gadgets. Tools are everywhere — on shelves, on worktables, on the floor.

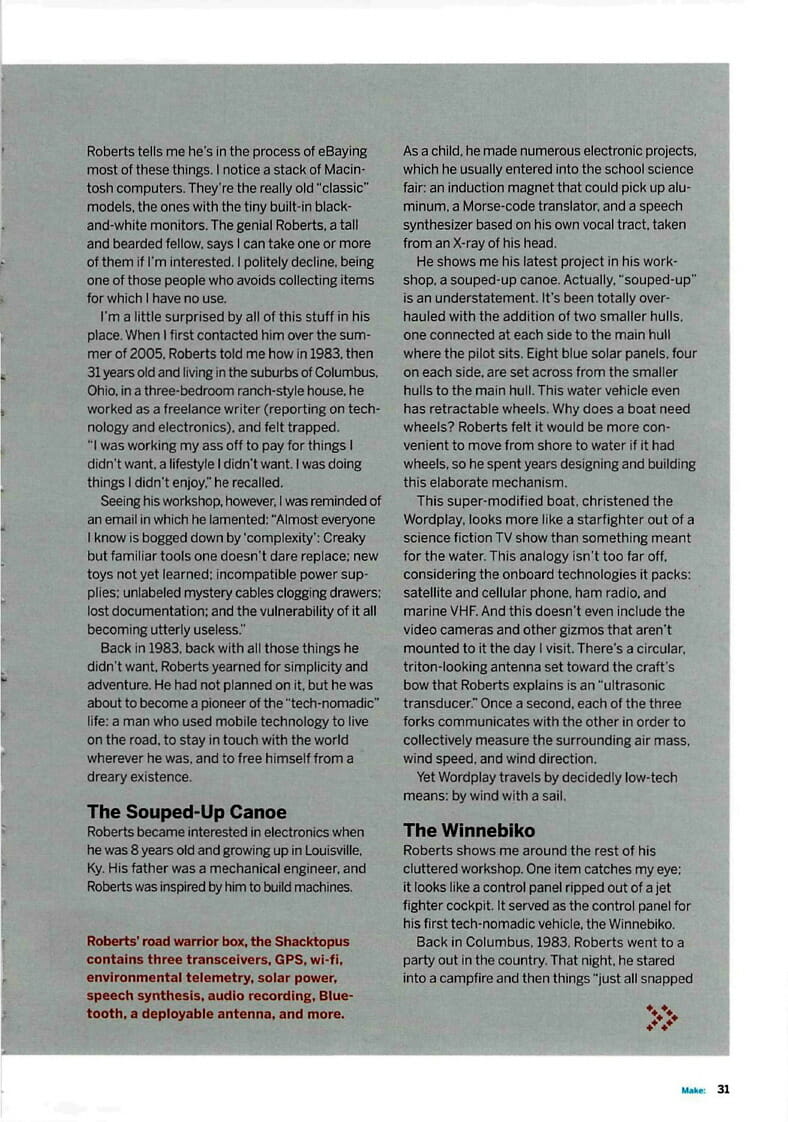

Roberts tells me he’s in the process of eBaying most of these things. I notice a stack of Macintosh computers. They’re the really old “classic” models, the ones with the tiny built-in black-and-white monitors. The genial Roberts, a tall and bearded fellow, says I can take one or more of them if I’m interested. I politely decline, being one of those people who avoids collecting items for which I have no use.

I’m a little surprised by all of this stuff in his place. When I first contacted him over the summer of 2005. Roberts told me how in 1983, then 31 years old and living in the suburbs of Columbus, Ohio, in a three-bedroom ranch-style house, he worked as a freelance writer (reporting on technology and electronics), and felt trapped. “I was working my ass off to pay for things I didn’t want, a lifestyle I didn’t want. I was doing things I didn’t enjoy.” he recalled.

Seeing his workshop, however, I was reminded of an email in which he lamented: “Almost everyone I know is bogged down by ‘complexity’: Creaky but familiar tools one doesn’t dare replace; new toys not yet learned: incompatible power supplies: unlabeled mystery cables clogging drawers: lost documentation; and the vulnerability of it all becoming utterly useless.”

Back in 1983, back with all those things he didn’t want, Roberts yearned for simplicity and adventure. He had not planned on it, but he was about to become a pioneer of the “tech-nomadic” life: a man who used mobile technology to live on the road, to stay in touch with the world wherever he was, and to free himself from a dreary existence.

The Souped-Up Canoe

Roberts became interested in electronics when he was 8 years old and growing up in Louisville, Ky. His father was a mechanical engineer, and Roberts was inspired by him to build machines. As a child, he made numerous electronic projects, which he usually entered into the school science fair: an induction magnet that could pick up aluminum, a Morse-code translator, and a speech synthesizer based on his own vocal tract, taken from an X-ray of his head.

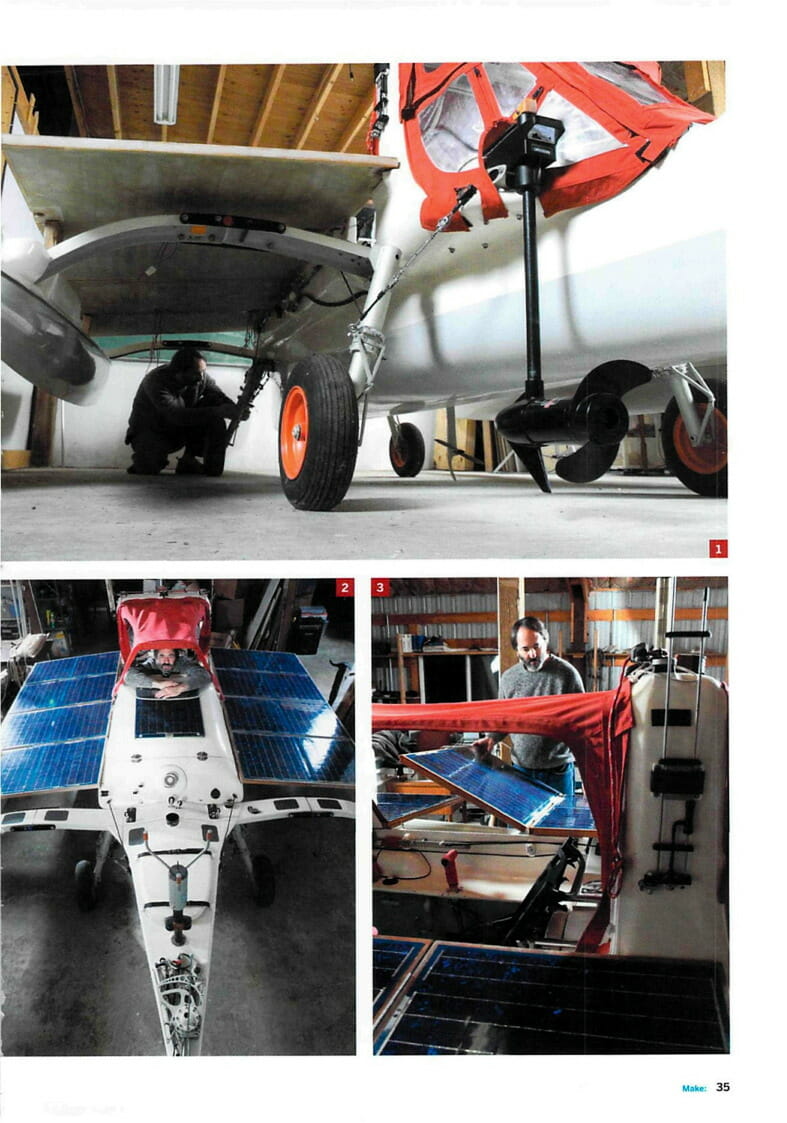

He shows me his latest project in his workshop, a souped-up canoe. Actually, “souped-up” is an understatement. It’s been totally overhauled with the addition of two smaller hulls, one connected at each side to the main hull where the pilot sits. Eight blue solar panels, four on each side, are set across from the smaller hulls to the main hull. This water vehicle even has retractable wheels. Why does a boat need wheels? Roberts felt it would be more convenient to move from shore to water if it had wheels, so he spent years designing and building this elaborate mechanism. [note: credit is due here to Bob Stuart, who did most of the landing gear design.]

This super-modified boat, christened the Wordplay, looks more like a starfighter out of a science fiction TV show than something meant for the water. This analogy isn’t too far off, considering the onboard technologies it packs: satellite and cellular phone, ham radio, and marine VHF. And this doesn’t even include the video cameras and other gizmos that aren’t mounted to it the day I visit. There’s a circular, triton-looking antenna set toward the craft’s bow that Roberts explains is an “ultrasonic transducer.” Once a second, each of the three forks communicates with the other in order to collectively measure the surrounding air mass, wind speed, and wind direction.

Yet Wordplay travels by decidedly low-tech means: by wind with a sail.

The Winnebiko

Roberts shows me around the rest of his cluttered workshop. One item catches my eye; it looks like a control panel ripped out of a jet fighter cockpit. It served as the control panel for his first tech-nomadic vehicle, the Winnebiko.

Back in Columbus, 1983. Roberts went to a party out in the country. That night, he stared into a campfire and then things “just all snapped into place”: why not combine the things he was most passionate about — computers, writing, travel, bicycles, and romance — into a new life?

He ordered a custom-built recumbent (a type of sit-down bicycle), then grafted on a RadioShack TRS-80 Model 100 laptop, a Hewlett-Packard HP-110 portable computer [the HP was added a year later], CB radio, and a 5-watt solar panel to power these gadgets. He named the resulting vehicle the Winnebiko.

Starting from Columbus, Roberts biked 10,000 miles, passing through small towns along the southern East Coast, through Florida, the South, Texas, and the Southwest, and ending in Silicon Valley in California about 18 months later. Throughout this trip, he continued to earn a living by writing articles on his laptop. He also wrote about his journey, which eventually caught the notice of people in the media, who wondered about this man bicycling across America on a “computerized bike.”

As fulfilling as this really long bike ride had been, he found it frustrating that he could not write while riding at the same time. “I had all this mobility, but I was just watching the words flow away, knowing by night, when I was camping or whatever, I would not capture these thoughts,” he says.

Roberts upgraded the Winnebiko for an encore trip in 1986. The Winnebiko II added packet radio for email access, a security system with motion detection and voice synthesis, and a new, more sophisticated control panel. To enable himself to write as he pedaled, he hacked apart the keyboard of the TRS-80 Model 100, and rewired the keys to the bike’s handle controls. [actually, this was a chord keyboard with a 68HC11 controller that emulated the Model 100 keyboard]

His second bike tour ran from Seattle, along the West Coast, and across the country to the East Coast. He was accompanied by his girlfriend at the time, Maggie Victor, who rode her own recumbent. Together, they traveled 6,000 miles.

Behold the BEHEMOTH

The attention Roberts got from the media led to interest from corporate sponsors. From 1988 to 1992, he threw more things onto the Winnebiko II. A lot of things. Much like a succeeding version of a Microsoft application, the bike quickly became bogged with too many features, to the point of absurdity and uselessness. So many components were put on it that a trailer had to be designed to hold them, and for the bike to tow.

Renamed BEHEMOTH (Big Electronic Human-Energized Machine… Only Too Heavy), it was assembled in Silicon Valley by a team of volunteers assisting Roberts. It had almost every piece of mobile and computer technology at the time: a hacked Macintosh and other computer systems, tons of radio communications devices, GPS navigation, even a radiation monitor.

“I got so distracted by the tech stuff,” Roberts admits. “I’d be reading a trade journal and go, ‘Ooh, ooh, I could use that!’ and then I would schmooze and get it.”

The media and public were enchanted with his journeys, and wowed by the technology-laden, though impractical, bike. Roberts was interviewed by many reporters and appeared on TV talk shows. But as public interest in his project was reaching its peak, the tech-nomadic biker’s passion for his original dream was dying. Ironically, to make public appearances and do speaking gigs, he traveled the country in a diesel truck that carried the BEHEMOTH in its trailer.

The Laboratory on an Island

Using the money he earned from his speaking tour for the BEHEMOTH, Roberts bought property on Camano Island, choosing the region for its variety of surrounding waterways. He put up the 3,000-squarefoot workshop to facilitate the research, construction, and testing of small watercraft that would utilize tech-nomadic technologies. He brought over the volunteer-community ethic of BEHEMOTH by inviting engineers and other specialists to take part.

The “Microship Project” began with the idea of outfitting a basic kayak with communications devices, but evolved into a pair of specially modified boats, Songline and Wordplay. These water vehicles expanded upon the embedded systems technologies that Roberts and his BEHEMOTH team developed, and which allowed the pilot to control almost every aspect of the craft through a Palm-OS PDA. [Note: the Microship project used a wireless Apple Newton for front-end control over a network of FORTH boards; migration to Palm OS did not happen until the Shacktopus project.]

In his workshop, Roberts shows me the inside of a thick plastic project box that’s sitting at one end of a worktable. It looks large enough to hold several hundred sheets of 8.5×11 paper. This is the power supply he designed for the Wordplay [correction: the power control system was designed and built by Tim Nolan]. It uses seven microprocessors to regulate and distribute 600 watts. While the boat’s solar panels alone can provide 5 knots to move the craft, this power unit was also designed to enable the pilot to divert all power to the thrust for emergencies (like quickly veering away from another boat).

Roberts took the Wordplay on a 132-mile ride through Puget Sound in September 2001. Though he still considers it to be in development, the Microship Project has gone through extended inactive periods over the years, as personal priorities for him shifted.

“When I started this ten years ago, I was perfectly pleased with the idea of taking out on a canoe-sized hull, spending two years sleeping in the bilge — it’s the size of a coffin. Now I’m 52, and I’m like, ‘I don’t want to be that uncomfortable for that long!'” he says, chuckling.

Project Shacktopus

Along with a weakening tolerance for physical discomfort, Roberts has been wondering lately if maybe he has spent too much time over the past 20 years designing machines and not enough of it going out on actual adventures. He calls this consequence the “BEHEMOTH effect.”

Thus, last year he decided to create an all-in-one mobile communications pack, which he named the Shacktopus. He plans to make it the size of a notebook computer, or small enough to fit into a messenger bag. It’s the first project of his that he hopes to turn into a commercial product.

“Unlike the other systems [Winnebiko, et al.]. which were really lifestyle choices, this is much more ‘grab and go.'” he says. “With Shacktopus, I’m avoiding any more multi-year projects that tie me to a specific bike or boat.”

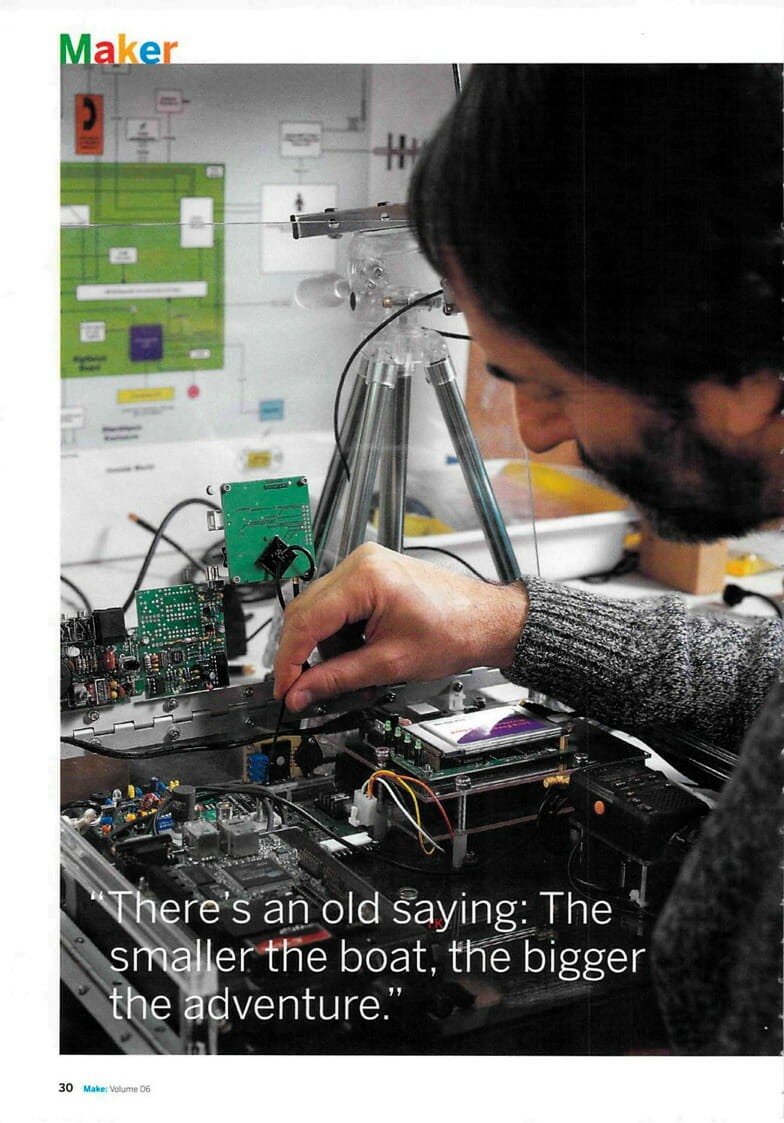

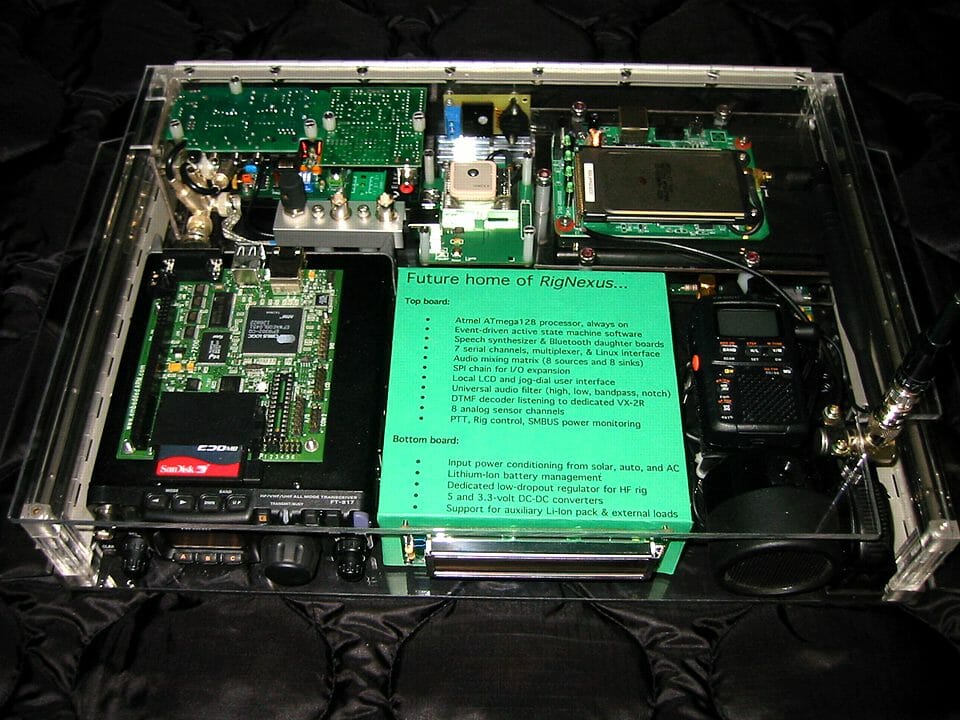

He shows me the prototype for the Shacktopus, sitting on the same worktable where he has the power supply box for the Wordplay. The Shacktopus is essentially a clear plastic project box with a medley of off-the-shelf communication and other computer components inside, bashed and interfaced together through a unified control system designed by Roberts. There’s an HF/VHF/UHF transceiver: a GPS system; environmental telemetry; internet access with wi-fi bridging; a lithium-ion battery power system that can be charged by a solar panel, automobile cigarette lighter, or AC outlet; speech synthesis; audio recording; Bluetooth interfacing to a notebook computer or PDA; and a deployable antenna array from HF to 2.4GHz.

For something that’s supposed to help simplify Roberts’ life, to free him from dealing with such technically complicated projects as the Microships, this early version of the Shacktopus itself already looks to be… complex.

While it stems from the restlessness that has been growing within its creator over the past few years, the Shacktopus also seems to represent the same conundrum. Roberts came to the woods of Camano Island with what sounded like a simple enough plan: build a boat and move on to the next big adventure. This didn’t happen fast enough. Apparently, it takes a long time to build a boat, at least the way Roberts likes to build one, thanks to fancy things like retractable wheels. Things became complicated.

“I want to get moving again, and I see Shacktopus as the way of making that happen — kind of short-cutting that whole process.” he says, perhaps hopefully. “I’m looking for a big boat that I can live on and do some world traveling.”

The Allure of Human Power

When I started talking to Roberts for this story last summer, I immediately noted that his technomadic vehicles — the bikes and the boats — shared the distinction of being small vehicles that relied mainly on people power. I wondered what the appeal in that was for him.

“I like the human scale of it. I find that when you cruise on a motorcycle or car, you’re really anonymous. You’re just somebody passing through on the freeway. Whereas, when I was on a bicycle. I was completely non-threatening,” he said to me back then. “Back in the early 80s when I was [biking through] small towns in the South, people would take me home. They weren’t worried about me. Also, it’s a lot more satisfying. Kayaking to an island is more exciting. There’s an old saying: the smaller the boat, the bigger the adventure.”

Afterwards, I mused for several months: what could be the thematic connection of a human-powered vehicle, or wind- and solar-powered one (as in the case of the Microships), to mobile communications technology? What was the appeal of the two brought together?

When I meet the tech-nomadic pioneer in person on a sunny afternoon in February 2006, I ask him about this. Beyond the fact that the two subjects have always interested him personally, he cannot come up with some profound, satisfying explanation for it all.

I climb aboard the Wordplay — or climb into it, to be more precise. At 5’8″, I’m much shorter and thinner than Roberts, so the inside doesn’t feel “coffin-like” to me at all. There’s a lot of leg-room. I fiddle with some of the levers and try to relax myself into the hard seat. I look ahead, out the canopy. A compass is affixed to the top of the dashboard, and beyond that I see a large marker board with technical-looking diagrams drawn on it, hanging from the wall in front of the Wordplay. If I were on Puget Sound, my view instead would be of the water rippling out beyond and into a backdrop of the mountain ranges of northwestern Washington, I imagine. But it also feels like I’m in a starfighter.

It then gradually dawns on me: there’s a unique feeling about being inside such a small craft that relies upon your own physical skills and wits to control. It becomes like an extension of your own skin, your own body. It becomes personal.

Maybe that’s the connection: mobile communications, and vehicles like Roberts’ bikes and this boat, both evoke a personal, emotional bond between themselves and the user. The more physically invested the rider is in the direct powering of the vehicle, the more personal the journey becomes.

“My goal is not to spend my life in the lab building electronics,” Roberts says. “I got this beautiful place in the woods. It looks like it ought to be paradise, but I’m just itchin’ to get moving again.”

The last time he felt that itch, he was living in a three-bedroom, ranch-style house somewhere in the suburbs of Columbus. There was no eBay, so he was stuck with a bunch of unwanted stuff that he couldn’t easily get rid of.

But one day, he left it all behind — there were still dirty dishes in the kitchen sink — and didn’t even bother to lock the front door of his house. He just pedaled away on an odd-looking bike that he had slapped computers and mobile communications gadgets onto. “It was like I reached around the back of my head and hit the reset button,” he says of that day when his journey began.

The Shacktopus system that was discussed in this article got a sweet accolade in 2015, when I gave a talk at Google. As I spoke of this backpack-scale system with its sensors and communications paths, showing the block diagram below, someone in the audience called out… “hey, that was the first smart phone!”

[…] Steve Roberts was also an early hardware hacking pioneer, writing his first self-published book, Computing Across America (in the late ’80s) literally from the seat of his tricked-out, gadget-laden, internet-connected bike. This new, deceptively slim volume contains 25 years of Roberts’ trade secrets on how to capitalize, publicize, and find support for your own “gonzo engineering” projects. It’s meta-hack project wisdom from the original high-tech nomad (see MAKE, Volume 06, page 28, “Tech-nomading from Shore to Ship”). […]