Roamin’ Free, but Plugged Into the Job – USA Today

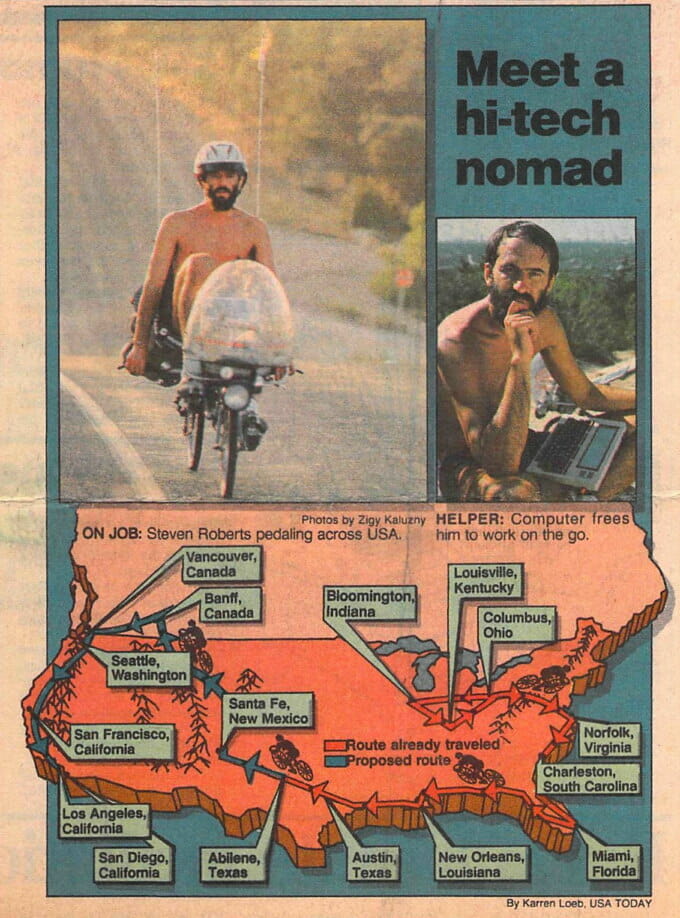

During the primitive beginning of my paleo-technomadic bicycle travels, the media was yet unfamiliar with the implications of the technology that was making it possible… even though vibrant communities were developing in various pre-Internet online services like CompuServe. After a small article about my trip appeared in USA Today (May 1, 1984), I got a contract with them to do a regular column from the road… and this cover story in the Money section was the first in the series.

by Steven K. Roberts

USA Today

July 5, 1984

Biker’s work and play is just a phone call away — via computer

Free-lance writer Steven Roberts, 31, is traveling the USA with a personal computer while writing his fourth book, Computing Across America, to be published in 1985 by Simon & Schuster. This is the first in a series of accounts of his travels that will appear in USA TODAY.

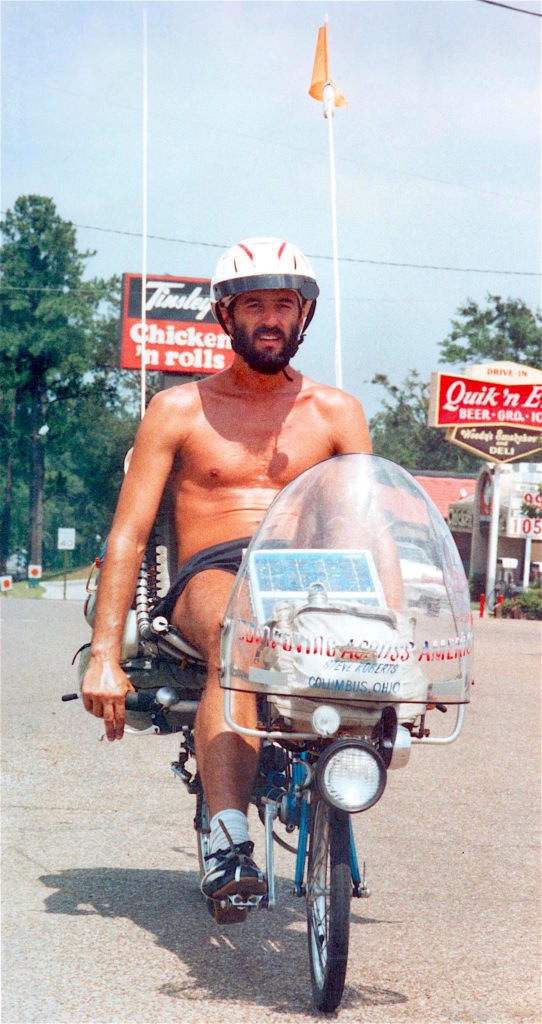

Last September, I sold my Ohio home and moved to a bicycle. For almost nine months I have been living (and making a living) on the road, with more than 5,700 miles behind me and at least twice that many to go.

This isn’t one of those midlife career changes, nor is it a madcap escapist odyssey. It is an adventure, of course, but it’s also a full-time profession, profitable and self-sustaining. I have become a high-tech nomad — a mobile free-lance writer of the information age.

Such a lifestyle would not be possible without the support of technology. On the bike with me is a four-pound portable Radio Shack Model 100 computer, and in a Columbus, Ohio, office is a computer system under control of my assistant. Our means of communication is CompuServe, a nationwide computer network through which I can conduct not only business correspondence but much of my personal correspondence as well.

Computers and telecommunication networks may seem odd things to associate with long-distance bicycle touring. The bike itself is a low-slung, 8-foot-long model equipped with a lawn chair-like seat, solar panels, security system, communications gear, dictation equipment and more, suggesting a severe case of gadget-mania. But these are the very elements that have come together to make a nomadic business possible. From any telephone in the country, in fact, I can:

- Interact electronically with hundreds of thousands of network subscribers — writers, students, doctors, farmers, politicians, engineers, pilots, movie moguls, friends.

- Maintain the illusion of stability by handling my finances, negotiating contracts and performing writing and consulting jobs — all through regular communications with my fixed office in Ohio.

- Gain instant access to computer databases containing information ranging from business statistics to medical literature, from current periodicals to Who’s Who, from patent files to the combined Yellow Pages of the entire USA.

- Use the computer to shop for a new sleeping bag, check stock quotations and read the latest world news.

- Ask advice about the diseases of goats, the quirks of various computers, or the fine points of copyright law — from online special interest groups of experts and hobbyists.

- Publish an ongoing account of my travels and receive electronic feedback in the form of suggestions, offers of accommodations, or just plain encouragement.

At any pay phone, I have access to more information than can be found in any single library in the world. And I can do business as effectively as if I were still back in my office.

On a wet morning in East Texas, for example, I took one look at the dark sky that was delivering a much-needed downpour to the drought-wracked soybean fields.

There would be no cycling that day.

I rolled under the canopy of a gas station, bought some coffee, then hunkered down on the pavement beside a pay phone, my computer case open in front of me.

I attached a pair of rubber cups — acoustic couplers — to the handset, dialed CompuServe, and within moments, I was online.

After giving my user identification number and password, the system delivered the news that I had eight letters in my electronic mailbox.

It proceeded to transfer them into the memory of my portable computer while I sipped coffee, chatted with curious bystanders, and tried to keep a wet and exuberant Labrador retriever at arm’s length.

Four were fan mail on recent articles and a couple were personal — a flirtatious message from a friend in Florida and the latest news on a California friend’s book project.

Next, I logged into the CB Simulator, a kind of international electronic pub that is the prime gathering spot for CompuServe users.

A few friends were there — “Farquar,” “Sylphide,” “Conan the Librarian” — as well as a number of unfamiliar users. “Wordy!” came the enthusiastic greeting from Somewhere Out There, “Where U B??? How’s the trip going?”

I summarized my recent travels, then spent a few minutes in private conversation with a lady who offered me a place to stay in Tucson, Ariz., as the Texas rain continued to fall.

Anxious to get to the day’s work, I waved an electronic goodbye and moved to a different part of the system — the file area where I communicate daily with my Ohio-based assistant, Kacy.

I left a message for her, then electronically transmitted — “uploaded” — a short piece I had written the night before.

After a quick check of the week’s finances — a rundown of the latest bills and bank and credit card balances — I signed off and sauntered into the station for more coffee.

I settled down at a sheltered picnic table and plugged the computer into the bicycle’s solar power system to write an article about the National Weather Service for Online Today magazine — covering the week’s expenses in four or five hours.

This was just one of the temporary offices that have sprung up along my route. Oily with suntan lotion, I wrote a Popular Science article on a Key West beach.

I performed a consulting job from a tent on the banks of the Potomac.

I have plugged into the network from phones everywhere, prompting one small-town Ohio farmer to ask if I was with NASA and one Florida tourist to call urgently to her husband: “Honey, come quick — here’s a real show!”

From a business standpoint, the computer is highly liberating. There is no longer any need for me to sit in one place, surrounded by file cabinets, word processor, photocopier and so on.

I have broken the chains that once bound me to my desk — and I see more and more people doing the same thing. Retirees in motor homes, sales people on the road, consultants visiting clients, vacationers and the work-at-home crowd all are enjoying more personal freedom through telecommunications.

My social life has reaped dividends, too: Most of CompuServe’s 130,000 subscribers have heard of me by now, and I find in my electronic mailbox at least two invitations a day (“If you ever come to…”)

The lesson in all this is simple. While the liberating effects of personal computers have been breathlessly touted for years, it’s only recently that the machines have evolved to the point where they can be used by just about anyone.

Computers are no longer just for experts and tinkerers — they are truly “information appliances.”

Data bases are no longer just for librarians and researchers — they are public resources. Electronic mail is no longer just for businesses — it’s for anyone who has tired of the U.S. mail service.

Best of all, these things now are widely available and affordable — whether you’re at home, at work or pedaling the planet on a bicycle.