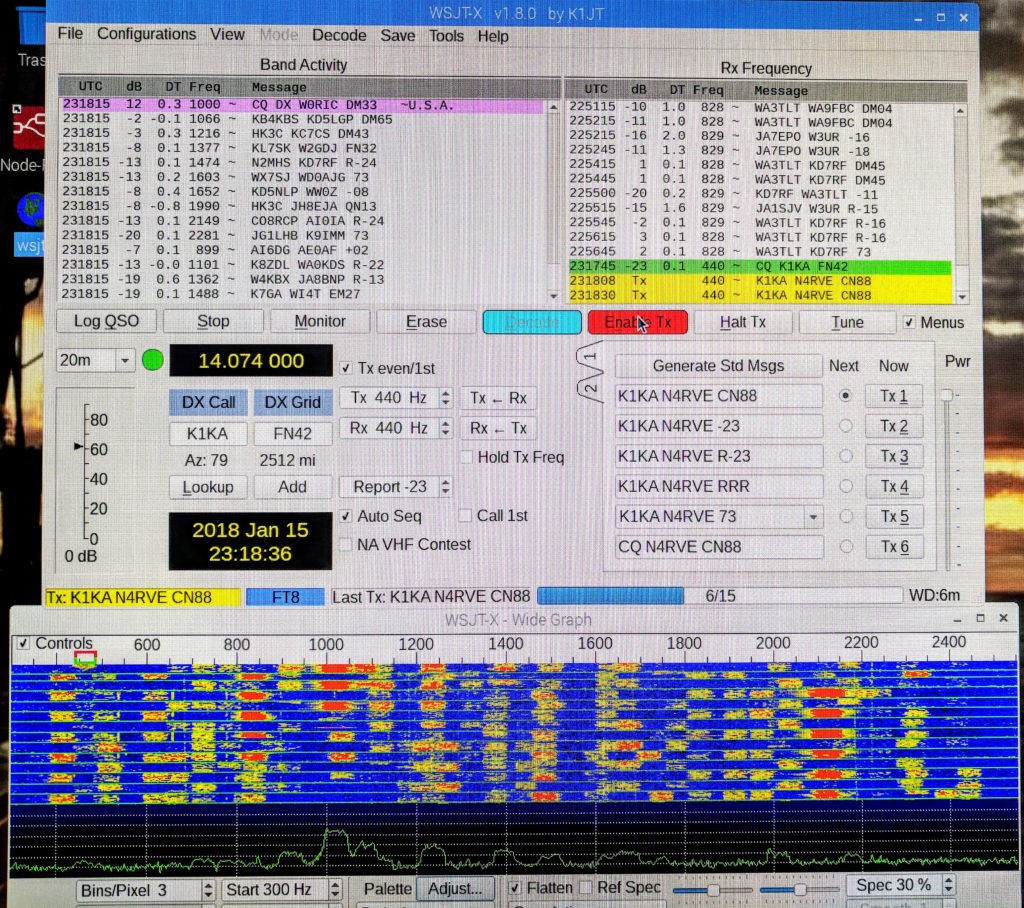

I’ve recently been enjoying immersion in a sort of ham radio for introverts… a new digital mode called FT8 that allows weak-signal communication on all the HF bands from 160 to 6 meters via tiny 50Hz-wide signals exchanged by time-synchronized computers running WSJT-X. A complete exchange takes a minute and a half, with the connected machines (Raspberry Pi in my case) handling decoding and encoding, controlling the radio, logging, and presenting the user interface shown in the screen photo above. It’s magical and geeky stuff, although not at all like traditional amateur radio; we don’t chat as such, but use automated tools to exchange signal reports and grid squares that define our location down to 1° latitude by 2° longitude (roughly 70×100 miles in the US). Although impersonal, this is weirdly satisfying for reasons that are hard to articulate. Perhaps this is because the mode is obviously FM (Effin’ Magic), using forward error correction and processing gain so substantial that in many cases, an exchange is not even audible when you crank up the old-fashioned volume control to hear tiny whistles down in the noise… with 20-30 at a time taking place on a single USB frequency.

People collect states, countries, and grid squares… and exchange mostly electronic QSLs. Here are the stateside connections I’ve made in the past three weeks of casual FT8 tinkering from the boat (plus a few elsewhere, including Japan). My location is in the upper left corner, in grid square CN88:

A particularly enchanting thing about this is that there is also a website called PSK Reporter that collects data from thousands of stations (including mine), and displays real-time activity on a world map. I can send a CQ and see exactly where in the world my signal is being heard. This provides a window into propagation conditions that would have been unimaginable to hams of yesteryear… you can watch gray line effects, correlate observed skip distance with propagation and space weather reports, and get immediate feedback on local tweaks to your transmit power or antenna configuration.

Firing up the Station

As an obsessive gizmologist with interests ranging from amateur satellites and 3D printing to submarines and virtual reality, I have a problem: I am annoyingly finite. Every new toy that catches my fancy gets meticulously researched, usually leading to acquisition of whatever solution seems to be the best within constraints of space and cost. Often, I manage to physically integrate the new gadget into the starship… but, too often, it then sits unused as I am drawn into a new quest by the pheromonal allure of another novel technology.

This happened with the ham radio gear aboard Datawake, which includes the highly capable Icom IC-7300 along with a few other rigs lovingly packaged into console zone Delta… not to mention two antennas that have been cluttering the pilothouse console for about a year, accessories gathering dust, SDR devices awaiting interfacing, and even a few software licenses paid for and not yet downloaded. I’m spread thin, with way too many projects, and that bothers me.

Occasionally, something will spark a sudden burst of enthusiasm, and in this case it was my friend Paul, WB6CXC, who had been playing with FT8 for a few weeks. He showed up on the boat one day, armed with a Raspberry Pi pre-configured with WSJT-X. We dropped it onto the ship’s LAN (for network time services as well as general connectivity), ran USB to the Icom rig, borrowed console hardware from the PC over on the media desk, and tweaked the 7300 settings with help from a few YouTube videos.

The only HF antenna I had topside at the time was the 23-foot vertical owned by the Icom M802 marine SSB rig, so we used that to configure the tuner to the 30 meter FT8 frequency (10.136), dragged the coax across to the other rig, and gave it a try.

And whaddya know! Danged if the thing didn’t immediately start decoding, showing the occasional CQ drifting by, though my antenna system was not behaving and we didn’t get to break in the new log with any contacts. He left the little box with me as a Christmas present, then headed home so we could try a short range QSO. And indeed… a few minutes later, we managed one each on 30 and 40 meters. That immediately launched me on a quest for my first contact “in the wild,” and before long I worked WC6YJ in Los Gatos.

All this was motivating, and it was time for a proper skyhook. My Shakespeare 393 vertical antenna is a typical 23-foot marine stick but is saddled with a terrible counterpoise, kluged to the rail with inadequate copper; even mated to the AT-140 tuner that was a hot performer on the steel-hulled Nomadness a few years ago, it has not been much fun. I’ve been meaning to get a dipole up anyway, so this was a good excuse. I gathered the thicket of Diamond HFV5 resonators gathering dust in the pilothouse, then stood around on the upper deck for a while trying to find a way to mount the gangly contraption that would not involve ladders, bungees, duct tape, molded fiberglass parts, custom machining, shipping delays, or things I would keep putting off until the passion fades. Hmm… there’s a hunk of rail on the stern right here, only about 3 feet off the deck, but easy. Why not? It should be enough for a test. I dug around in the bin of Nautical Tinkertoys and found enough parts to mate the dipole assembly to the stanchion:

That’ll do for the moment, though the stubby flange mount is only held into the tee with a single Allen screw and it would definitely not survive rollicking seas. But there is something in the twisted psychology of ham antennas… get that thing up today so we can get on the air! I flopped a too-long hank of RG-58 down to the rig in the console, snaking it through a cracked-open window and across the desk instead of properly shortening, re-terminating, and tucking it low and away from computers (see where this is going?), then assembled the multi-band dipole that my friend Laurie of the San Juan Island Library aptly called Scarecrow with Jazz Hands. Here’s the stern half:

I fired up the rig, tried transmitting, and YOW! Some serious SWR, on the order of ∞:1. Could it really be that awful? I played with it for a while anyway, and not surprisingly started having computer problems… Mac trackpad flaky, Zebra postage printer locking up, waterfall on the Pi freezing and needing reboots. I looked at the VSWR curves in the HFV5 antenna documentation (PDF link), and used my CAA-500 antenna analyzer to confirm the extremely narrow tuning, about 10 kHz wide. This thing is sharp, requiring careful .6-inch lengthening of the tip rods to move the minimum SWR point down to 14.074 from somewhere just above the upper 20-meter band edge where it didn’t belong anyway.

With that, performance astounded me. I made contacts one after the other, across the US, Hawaii, Alaska, Cuba, and Japan. I mostly hung out on 20 meters, but occasionally moved to 40, and started to find my way around the standards and protocols of this mode. There are some issues… etiquette, emerging standards for dealing with DX pileups by working split, questions about what constitutes completion of a QSO before an eQSL is issued… but being non-competitive and just into it for geek lulz, I was competing only with myself, chasing grid squares and states. I suppose I will link my automatically generated log to one of the online services like LOTW (Logbook of the World) just to confirm contacts; even though I’m not chasing wallpaper, other people are and might like my island QTH even though the square is not rare.

The technology is fascinating and astoundingly sensitive, though of course it suffers when abused; naturally some folks use Big Guns to crush the competition while chasing DX. But for the most part, it is very well behaved, with only the occasional hidden-transmitter problem causing overlaps or other glitches in what is basically a self-organizing waterfall of signals. This is the magic of this mode; what you see in the image below is a single receive frequency, with each column of blobs representing a simultaneous exchange (or series of CQ calls) taking place at a spot in the audio passband… each requiring about 50Hz of bandwidth as shown in the scale at the top. The thin horizontal lines represent 15-second intervals, and all FT8 stations are tightly synchronized to network time servers. The software analyzes teensy little tones that warble back and forth by 6.25 Hz, with each transmission being 75 bits plus a 12-bit CRC code for forward error correction. Signals can be decoded down to about -20dB, and exchanges are automated (but require manual initiation to keep stations from turning into automated QSO robots). Along the bottom, you can see a sort of scope trace that shows the strongest signals, but it is not uncommon to decode stuff that you absolutely cannot hear even if you crank up the volume.

As with many such things, a certain amount of good behavior is necessary… dumping out a kilowatt would ruin things for everybody, and some folks take liberties with the standard messages beyond adding a target state or DX to a CQ. I saw one today; I had a challenging QSO going and someone else started calling CQ on top of us; my counterpart briefly edited his custom message to say QRM PLS MOVE! We did complete the exchange, so it must have worked.

The other day there was a guy in southern California on the low end of the audio spectrum, blasting out a very hot signal (or at least getting awesome propagation)… and at the same time I saw this up at the high end of the waterfall:

This mystified me, so I did a quick QSY from FT8 to FB (the helpful FT8 Facebook group), posted the photo above, and had the answer within minutes… those are harmonics from an over-driven signal at the low end (this was at 3X his audio frequency). Almost immediately, he moved to the top of the audio passband, so I had to wonder if he was monitoring social media on the side… <grin>

There is a lot of documentation out there, so I won’t go into any more tech detail… but suffice it to say that it is kind of magical, albeit impersonal. I call it “ham radio for introverts,” and while I do miss the occasional friendly chat (and will get back to that, now that the dipole is finally up) I do find it satisfying to bang out a few contacts over coffee without having to feign cleverness.

At the beginning I mentioned PSK Reporter, which allows something that would have mystified hams back in the Olden Days: real-time display of propagation. Here is a screen capture that shows my activity earlier this afternoon on 20 meters, with my signals skipping off the ionosphere and essentially creating no ground wave (I’m in the upper-left corner at the small yellow push-pin, and the time flags are actual reception reports):

Using this tool, I’ve learned more about the nature of the various bands in the past three weeks than I ever did from articles on propagation theory. You can even see the gray-line effect, pulling back and looking at the whole world, with reports scattered along the path of the boundary between day and night (great time to work Asia, when our evening is their morning).

Station Hardware

It’s nice to have a few more elements of the Datawake console doing useful things, so I thought I’d show you the key components that have made the above possible. First, of course, there is a radio… the IC-7300 with color screen in the lower-left corner of zone Delta:

Audio routing gear is to the right and includes the W2IHY iBox, but that is not needed for this application. The rig is being completely controlled by a Raspberry Pi running the WSJT-X software:

The connections, from lower-left to upper-right, are:

- 5 Volt micro-USB power

- HDMI output to monitor

- Ethernet to ship LAN

- USB keyboard and wireless mouse receiver

- USB cable to IC-7300 transceiver

Desk clutter and tangles of wire drive me crazy, and this project was exactly the inspiration I needed to do something that has been on the list for a year: add a monitor on an arm at the end of the console, with a switching system to allow it to be passed around among the various small computers that need a basic hardware user interface. I did this with a Kinivo 5-port HDMI switch, with a couple of extra ports added via an older 3-port unit from the same company. These are attached to the underside of the desk, along with a pushbutton that cycles a 4-port USB peripheral sharing switch that moves a cluster of devices (keyboard, mouse, thumb drive, etc) among four different computers.

The arrangement is a little fiddly, of course… modal states can lead to confusion, especially with 7 monitors via cascaded switches and 4 USB clients with LED indicators hidden around the end of the console, but at least it’s now possible to get a native display on a new Pi that is not yet running VNC or web clients via the LAN. This also provides a console for the Intel NUC that owns the various other communication tools (software-defined radios, Uniden scanner, Rigol test instruments, radio interfaces, legacy packet, PACTOR email, other 7300 applications, and so on).

The business end of all this saves me from having to keep “borrowing” the screen and input devices from the Holodeck. The monitor arm is part of the “Amazon Basics” product line, but is actually made by Ergotron… and it is wonderful. When not in use, the Asus 21.5″ monitor tucks around the left end of the console, out of the way; when active, it can be optimally positioned above the desk anywhere around the two left-most cabinets (Alpha and Beta). Here, you can see it running FT8 with the little HDMI switchers visible under the edge of the desk:

The current video “channels” (four of which also get keyboard/mouse, thumb drive, and spare) are:

- Raspberry Pi for FT8

- Raspberry Pi for ship data collection (Node-RED)

- Raspberry Pi for audio streaming in and out of MOTU environment

- Intel NUC for comm and test equipment applications

- Analog-HDMI converter for general video display use, routed through Extron 8×8 switcher

- Secondary Roku/Chromecast/Whatever for video streaming (primary is in forward cabin)

- Spare

Of course, once the Pi projects are integrated, they can move to web interfaces; this is what I do with the other two aboard (Octopi for 3D printing with the LulzBot Mini, and PiAware for the ADS-B feeder). But this setup allows tinkering with native out-of-the-box tools, and is not dependent on a working network.

When it’s time to put the toys away and clean up, the monitor simply swings around and snuggles against the end of the console (where it will be retained by a foam pad and bungee loop before we do anything rowdy):

If you want to see the context of all this geekery in the boat lab, there is a detailed post about the console… including photos of the ham radio installation. It’s not finished yet; lots of cabling remains to be done, not to mention some essential fixturing before I cast off dock lines and stop being a maritime immobile station, but the overall system has become a solid suite of tools.

That all sounds great, but the truth is that computers, audio gear, and radios actually hate each other. There are more and more ferrites getting slapped on cables to reduce interference, and there is at least one kluge that is a work-around for what happens when a radio transmitter gets too close to KRK studio monitors… a remote-controlled power strip to shut them off when playing radio, lest they emit a loud 60 Hz hum. Packing all this into close proximity has its challenges, and another quirk is the amount of RF interference emitted by the the Philips Hue light strips that I otherwise adore. Look what happens on the waterfall of the IC-7300 when I turn them off… that bright mass of noise disappeared the moment they went dark:

When doing FT8, this sudden quiet translates into a dramatic increase in the number of active signals on the WSJT-X waterfall. I said “computer, turn off laboratory” about a minute before taking this photo:

Nothing electronic is ever as smooth and turnkey as we’d like… and thinking about this phenomenon, I could name a few other work-arounds that are necessary to adapt to quirks in the system, inevitable as we get to know the machines. Life on the bleeding edge, and all that. But the best part, and the point of this whole rambling post, is that there is Deep Pleasure in bringing gizmology online, using tools that have been lying fallow, conjuring blinkies, and seeing ever more antennas grandly raking the skies over Friday Harbor, out here in the wilds of grid CN88. See you on the air!

73 de N4RVE