Electronic Cottage on Wheels – Whole Earth Review

This has always been one of my favorite articles… it was an honor to publish in Whole Earth Review, produced by those brilliant folks in Sausalito who have brought us Whole Earth Catalogs and other treasures since 1968. The magazine ran from 1985-2002, and every issue was packed with ideas for self-sufficiency, new tools, and insights into looming changes that were yet but a glimmer on the mainstream horizon… always relaxed and fun to read, yet seriously thought-provoking. It is easy to fall into rhapsody when talking about this publishing entity, so having the opportunity to present my technomadic adventures in its pages was extremely gratifying. That bike photo was taken on Bainbridge Island while I was still building the console, and it didn’t even have the waterproofing side-panels yet. There is a lot more tech detail on that system elsewhere in this collection.

Electronic Cottage on Wheels

by Steven K. Roberts

Whole Earth Review

Spring, 1987

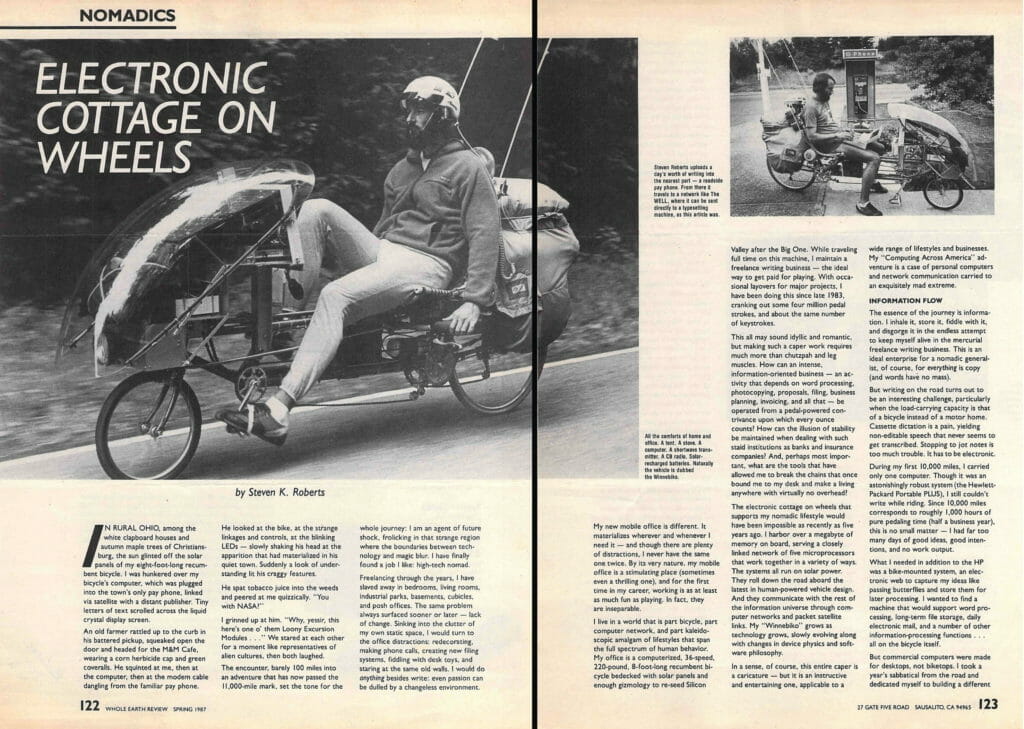

In rural Ohio, among the white clapboard houses and autumn maple trees of Christiansburg, the sun glinted off the solar panels of my eight-foot-long recumbent bicycle. I was hunkered over my bicycle’s computer, which was plugged into the town’s only pay phone, linked via satellite with a distant publisher. Tiny letters of text scrolled across the liquid crystal display screen.

An old farmer rattled up to the curb in his battered pickup, squeaked open the door and headed for the M&M Cafe, wearing a corn herbicide cap and green coveralls. He squinted at me, then at the computer, then at the modem cable dangling from the familiar pay phone.

He looked at the bike, at the strange linkages and controls, at the blinking LEDs — slowly shaking his head at the apparition that had materialized in his quiet town. Suddenly a look of understanding lit his craggy features.

He spat tobacco juice into the weeds and peered at me quizzically. “You with NASA?”

I grinned up at him. “Why, yessir, this here’s one o’ them Loony Excursion Modules…” We stared at each other for a moment like representatives of alien cultures, then both laughed.

The encounter, barely 100 miles into an adventure that has now passed the 11,000-mile mark, set the tone for the whole journey: I am an agent of future shock, frolicking in that strange region where the boundaries between technology and magic blur. I have finally found a job I like: high-tech nomad.

Freelancing through the years, I have slaved away in bedrooms, living rooms, industrial parks, basements, cubicles, and posh offices. The same problem always surfaced sooner or later — lack of change. Sinking into the clutter of my own static space, I would turn to the office distractions: redecorating, making phone calls, creating new filing systems, fiddling with desk toys, and staring at the same old walls. I would do anything besides write: even passion can be dulled by a changeless environment.

My new mobile office is different. It materializes wherever and whenever I need it — and though there are plenty of distractions, I never have the same one twice. By its very nature, my mobile office is a stimulating place (sometimes even a thrilling one), and for the first time in my career, working is as at least as much fun as playing. In fact, they

are inseparable.

I live in a world that is part bicycle, part computer network, and part kaleidoscopic amalgam of lifestyles that span the full spectrum of human behavior. My office is a computerized, 36-speed, 220-pound, 8-foot-long recumbent bicycle bedecked with solar panels and enough gizmology to re-seed Silicon Valley after the Big One. While traveling full time on this machine, I maintain a freelance writing business — the ideal way to get paid for playing. With occasional layovers for major projects, I have been doing this since late 1983, cranking out some four million pedal strokes, and about the same number of keystrokes.

This all may sound idyllic and romantic, but making such a caper work requires much more than chutzpah and leg muscles. How can an intense, information-oriented business — an activity that depends on word processing, photocopying, proposals, filing, business planning, invoicing, and all that — be operated from a pedal-powered contrivance upon which every ounce counts? How can the illusion of stability be maintained when dealing with such staid institutions as banks and insurance companies? And, perhaps most important, what are the tools that have allowed me to break the chains that once bound me to my desk and make a living anywhere with virtually no overhead?

The electronic cottage on wheels that supports my nomadic lifestyle would have been impossible as recently as five years ago. I harbor over a megabyte of memory on board, serving a closely linked network of five microprocessors that work together in a variety of ways. The systems all run on solar power. They roll down the road aboard the latest in human-powered vehicle design. And they communicate with the rest of the information universe through computer networks and packet satellite links. My “Winnebiko” grows as technology grows, slowly evolving along with changes in device physics and soft- ware philosophy.

In a sense, of course, this entire caper is a caricature — but it is an instructive and entertaining one, applicable to a wide range of lifestyles and businesses. My “Computing Across America” adventure is a case of personal computers and network communication carried to an exquisitely mad extreme.

INFORMATION FLOW

The essence of the journey is information. I inhale it, store it, fiddle with it, and disgorge it in the endless attempt to keep myself alive in the mercurial freelance writing business. This is an ideal enterprise for a nomadic generalist of course, for everything is copy (and words have no mass).

But writing on the road turns out to be an interesting challenge, particularly when the load-carrying capacity is that of a bicycle instead of a motor home. Cassette dictation is a pain, yielding non-editable speech that never seems to get transcribed. Stopping to jot notes is too much trouble. It has to be electronic.

During my first 10,000 miles, I carried only one computer. Though it was an astonishingly robust system (the Hewlett-Packard Portable), I still couldn’t write while riding. Since 10,000 miles corresponds to roughly 1,000 hours of pure pedaling time (half a business year), this is no small matter — I had far too many days of good ideas, good intentions, and no work output.

What I needed in addition to the HP was a bike-mounted system, an electronic web to capture my ideas like passing butterflies and store them for later processing. I wanted to find a machine that would support word processing, long-term file storage, daily electronic mail, and a number of other information-processing functions… all on the bicycle itself.

But commercial computers were made for desktops, not biketops. I took a year’s sabbatical from the road and dedicated myself to building a different system. The original intention — being able to type while riding — quickly evolved into a complete bicycle control and communications system — not only turning the Winnebiko into a mobile office but also starting so many on-the-street conversations that anonymity has become impossible. (That’s half the fun, of course, given the research potential of social contacts.)

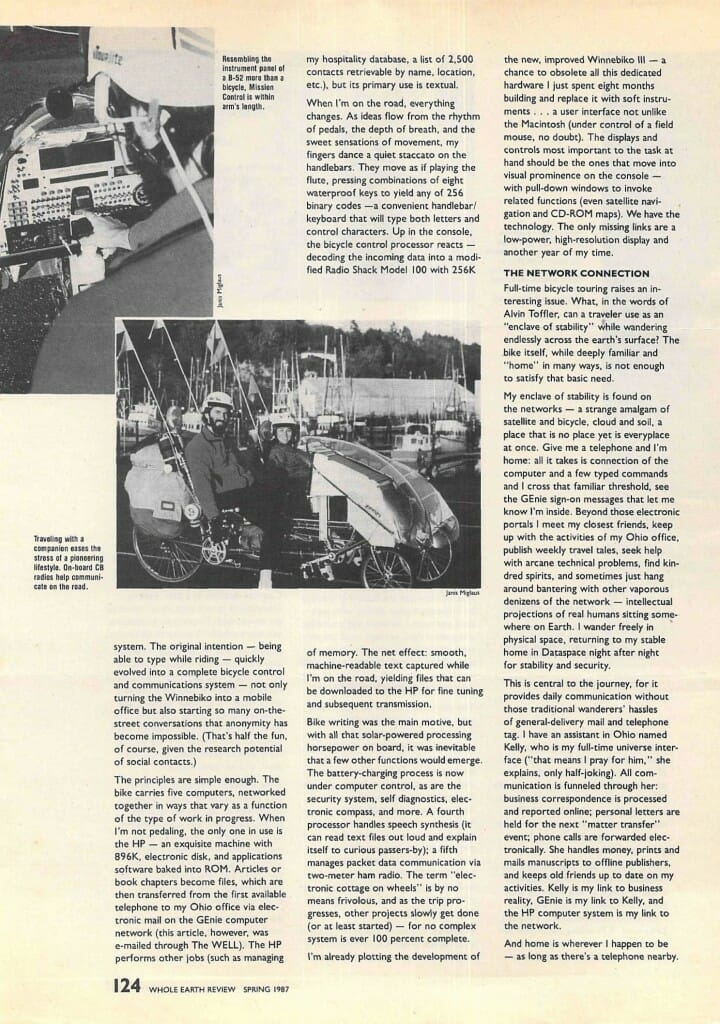

The principles are simple enough. The bike carries five computers, networked together in ways that vary as a function of the type of work in progress. When I’m not pedaling, the only one in use is the Portable PLUS — an exquisite machine with 896K, electronic disk, and applications software baked into ROM. Articles or book chapters become files, which are then transferred from the first available telephone to my Ohio office via electronic mail on the GEnie computer network (this article, however, was e-mailed through The WELL). The HP performs other jobs (such as managing my hospitality database, a list of 2,500 contacts retrievable by name, location, etc.), but its primary use is textual.

When I’m on the road, everything changes. As ideas flow from the rhythm of pedals, the depth of breath, and the sweet sensations of movement, my fingers dance a quiet staccato on the handlebars. They move as if playing the flute, pressing combinations of eight waterproof keys to yield any of 256 binary codes — a convenient handlebar/keyboard that will type both letters and control characters. Up in the console, the bicycle control processor reacts — decoding the incoming data into a modified Radio Shack Model 100 with 256K of memory. The net effect: smooth, machine-readable text captured while I’m on the road, yielding files that can be downloaded to the HP for fine tuning and subsequent transmission.

Bike writing was the main motive, but with all that solar-powered processing horsepower on board, it was inevitable that a few other functions would emerge. The battery-charging process is now under computer control, as are the security system, self diagnostics, electronic compass, and more. A fourth processor handles speech synthesis (it can read text files out loud and explain itself to curious passers-by); a fifth manages packet data communication via two-meter ham radio. The term “electronic cottage on wheels” is by no means frivolous, and as the trip progresses, other projects slowly get done (or at least started) — for no complex system is ever 100 percent complete.

I’m already plotting the development of the new, improved Winnebiko III — a chance to obsolete all this dedicated hardware I just spent eight months building and replace it with soft instruments… a user interface not unlike the Macintosh (under control of a field mouse, no doubt). The displays and controls most important to the task at hand should be the ones that move into visual prominence on the console — with pull-down windows to invoke related functions (even satellite navigation and CD-ROM maps). We have the technology. The only missing links are a low-power, high-resolution display and another year of my time.

THE NETWORK CONNECTION

Full-time bicycle touring raises an interesting issue. What, in the words of Alvin Toffler, can a traveler use as an “enclave of stability” while wandering endlessly across the earth’s surface? The bike itself, while deeply familiar and “home” in many ways, is not enough to satisfy that basic need.

My enclave of stability is found on the networks — a strange amalgam of satellite and bicycle, cloud and soil, a place that is no place yet is everyplace at once. Give me a telephone and I’m home: all it takes is connection of the computer and a few typed commands and I cross that familiar threshold, see the GEnie sign-on messages that let me know I’m inside. Beyond those electronic portals I meet my closest friends, keep up with the activities of my Ohio office, publish weekly travel tales, seek help with arcane technical problems, find kindred spirits, and sometimes just hang around bantering with other vaporous denizens of the network — intellectual projections of real humans sitting somewhere on Earth. I wander freely in physical space, returning to my stable home in Dataspace night after night for stability and security.

This is central to the journey, for it provides daily communication without those traditional wanderers’ hassles of general-delivery mail and telephone tag. I have an assistant in Ohio named Kelly, who is my full-time universe interface (“that means I pray for him,” she explains, only half-joking). All communication is funneled through her: business correspondence is processed and reported online; personal letters are held for the next “matter transfer” event; phone calls are forwarded electronically. She handles money, prints and mails manuscripts to offline publishers, and keeps old friends up to date on my activities. Kelly is my link to business reality, GEnie is my link to Kelly, and the HP computer system is my link to the network.

And home is wherever I happen to be — as long as there’s a telephone nearby.

BIKE ELECTRONICS

The computers are just part of the Winnebiko system, though their direct influence extends into every corner and their complexity has required an on-board microfiche documentation library. Of nearly equal value, from the lifestyle standpoint, is the communications gear.

My mobile ham radio station (call sign N4RVE) is a multimode two-meter transceiver made by Yaesu. In addition to handling packet data satellite communication (see WER #50, p. 47) with the aid of a Pac-Comm terminal node controller, it allows me to stay in regular voice contact with my traveling companion, Maggie (KA8ZYW). (Sharing a bicycle tour without some form of communication is frustrating, as anyone who as ever squinted into the mirror for minutes at a time well knows.) With a boom microphone built into my Bell helmet and a push-to-talk switch on the handlebars, Maggie is never far away (effective bike-to-bike simplex radio range is about two miles).

Of course, having two-meter FM capability on the bike also connects me to a vast network of ham radio operators. I store the local repeater frequencies in the radio’s memory as I approach an area, and periodically identify myself as an incoming bicycle mobile. Range in this case is upwards of 25 miles, since repeaters are generally in high-profile locations. This has led to a number of interesting encounters, and the autopatch systems often let me make telephone calls to non-hams directly from the bike.

A CB radio is also on board, culturally useless by comparison, but still valuable enough to justify its weight. I can talk to truckers, hail a passing motor home for water (this saved my life in central Utah), and shake my head at the idiomatic yammerings of the residual good-buddy subculture that hung on after the death of the great CB boom.

System security is as important an issue as survival when living on a machine that looks like a rogue NASA creation of incalculable value. But it’s not that people try to steal it — most are intimidated by the technology — it’s just that some let their curiosity extend to flipping switches and occasionally even climbing onto the seat and bending the kickstand. To alert me to such rude behavior, I added a paging security system with vibration sensors; when armed by a front-panel keyswitch, detected motion causes it to transmit a tone-encoded four-watt signal that triggers my pocket beeper up to three miles away.

Other radio-related devices include a Sony digital shortwave for international broadcast reception, a Sony Watchman micro-TV, and an FM stereo. Naturally, there is also an audio cassette deck, and a compact disc player is planned for under-dash installation soon. With this load, it sometimes takes a lot more than the usual granny gears to climb a mountain.

Then there is the matter of power. All the equipment described so far, plus behind-the-scenes control circuitry, requires electricity — in six different voltages. A pair of 10-watt Solarex photovoltaic panels serves as the primary source, providing about 1.3 amps to the 12-volt SAFT Ni-Cad batteries under ideal conditions. The charging process can be digitally monitored from the front panel, and the bicycle control processor intervenes if its calculations suggest that the batteries are in danger of overcharging. When too many cloudy days occur back-to-back, a power supply with line cord allows refueling from house current.

Generating the other voltages is a complex issue, but suffice it to say that new “switching power supply” devices have made high-efficiency voltage regulation relatively easy. The subsidiary supplies are switched in and out of standby mode as needed, and their outputs are available on the front panel to power tent lights, small radios, and similar accessories.

Other front-panel instrumentation includes the obligatory Cat-Eye solar bicycle computer to display speed, distance, cadence, and so on. This is flanked by an altimeter, a two-line LCD for the Etak electronic compass and other sensors, time and temperature display, and assorted status indicators.

THE BIKE ITSELF

Everything described so far has to be light, protected from vibration, kept dry even in the nastiest weather, and easy to repair on the road. Those requirements are added to an already stringent set of demands on the bicycle, for the total system (including my body) weighs 400 pounds. It must be pedaled up steep grades yet stop quickly; it must not oscillate under any conditions; it must withstand the ongoing abuses of weather and grime and shock and salt and overlooked maintenance.

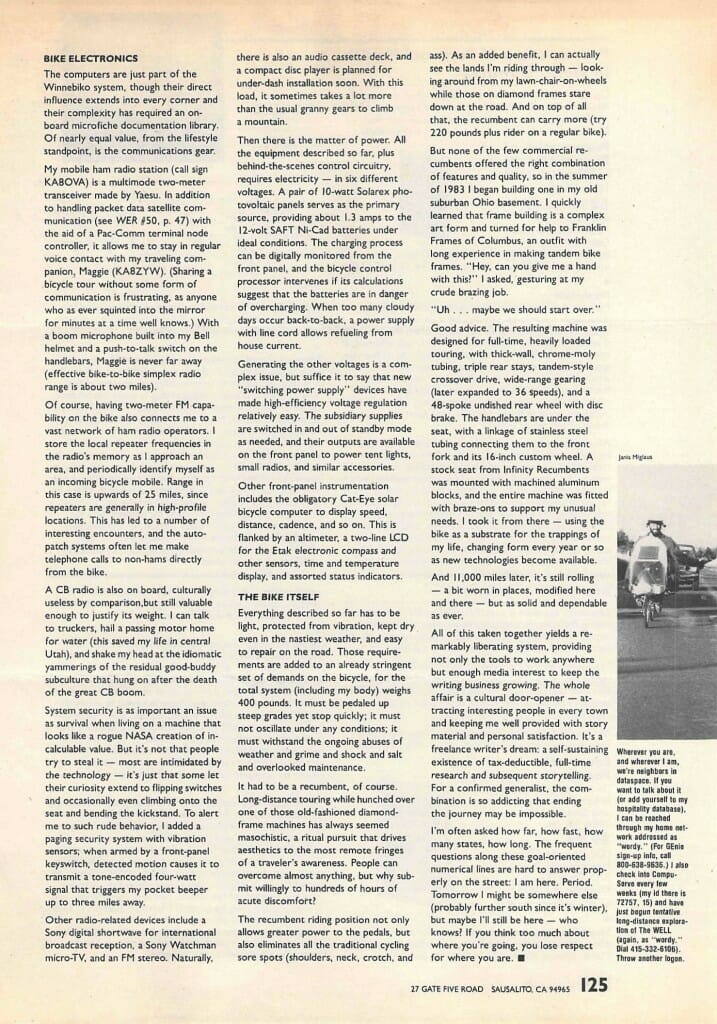

It had to be a recumbent, of course. Long-distance touring while hunched over one of those old-fashioned diamond-frame machines has always seemed masochistic, a ritual pursuit that drives aesthetics to the most remote fringes of a traveler’s awareness. People can overcome almost anything, but why submit willingly to hundreds of hours of acute discomfort?

The recumbent riding position not only allows greater power to the pedals, but also eliminates all the traditional cycling sore spots (shoulders, neck, crotch, and ass). As an added benefit, I can actually see the lands I’m riding through — looking around from my lawn-chair-on-wheels while those on diamond frames stare down at the road. And on top of all that, the recumbent can carry more (try 220 pounds plus rider on a regular bike).

But none of the few commercial recumbents offered the right combination of features and quality, so in the summer of 1983 I began building one in my old suburban Ohio basement. I quickly learned that frame building is a complex art form and turned for help to Franklin Frames of Columbus, an outfit with long experience in making tandem bike frames. “Hey, can you give me a hand with this?” I asked, gesturing at my crude brazing job.

“Uh . . . maybe we should start over.”

Good advice. The resulting machine was designed for full-time, heavily loaded touring, with thick-wall, chrome-moly tubing, triple rear stays, tandem-style crossover drive, wide-range gearing (later expanded to 36 speeds), and a 48-spoke undished rear wheel with disc brake. The handlebars are under the seat, with a linkage of stainless steel tubing connecting them to the front fork and its 16-inch custom wheel. A stock seat from Infinity Recumbents was mounted with machined aluminum blocks, and the entire machine was fitted with braze-ons to support my unusual needs. I took it from there — using the bike as a substrate for the trappings of my life, changing form every year or so as new technologies become available.

And 11,000 miles later, it’s still rolling — a bit worn in places, modified here and there — but as solid and dependable as ever.

All of this taken together yields a remarkably liberating system, providing not only the tools to work anywhere but enough media interest to keep the writing business growing. The whole affair is a cultural door-opener — attracting interesting people in every town and keeping me well provided with story material and personal satisfaction. It’s a freelance writer’s dream: a self-sustaining existence of tax-deductible, full-time research and subsequent storytelling.

For a confirmed generalist, the combination is so addicting that ending the journey may be impossible.

I’m often asked how far, how fast, how many states, how long. The frequent questions along these goal-oriented numerical lines are hard to answer properly on the street: I am here. Period. Tomorrow I might be somewhere else (probably further south since it’s winter), but maybe I’ll still be here — who knows? If you think too much about where you’re going, you lose respect for where you are.

You must be logged in to post a comment.