Aspen

Computing Across America, chapter 42

by Steven K. Roberts

Aspen, Colorado

September 16, 1984

(photo above by Jeffrey Aaronson, Aspen, September 1984)

My day was exciting too. I didn’t ride down any mountains, but I took Leah to the Beechwold Library and we got the baby carriage up to almost 5 mph on the sidewalk! Of course, there was a tailwind…

Kacy Branstetter

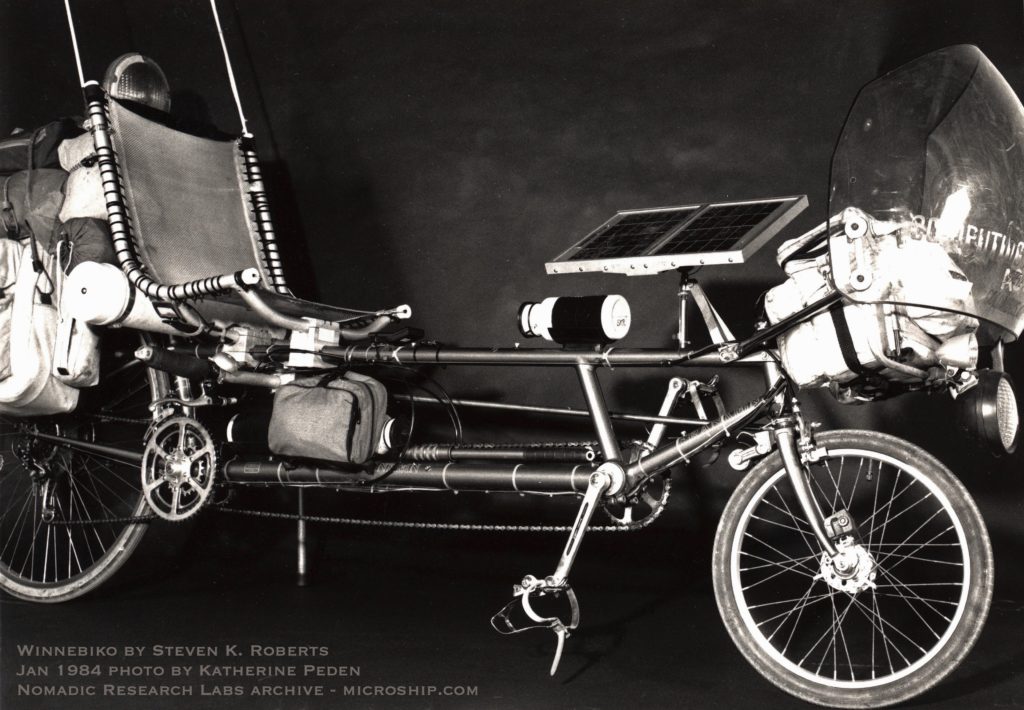

I stared at my machine, at the parts scattered around it, at the chain dangling loose where the rear wheel should have been. The Winnebiko was in pieces, hanging at an odd angle from a repair stand.

“Is there hope, doc?”

Steve Wolfe looked up from the workbench in Carbondale’s Life Cycles, his greasy hands smudging the rim of my ill wheel. “Well, the bearings have popped loose from the shell, but I don’t think it’s fatal. Red Loctite’ll fix it. Your brakes are a mess, though. You came down McClure in the dark on this?”

“Yeah, piece of cake,” I joked, almost startled by the brief panic-memory of the bouncing two-wheel drift around that tight switchback, the crunch of broken asphalt beneath my loose rear wheel, the sense of being half-airborne on a skittish machine with nothing but two little patches of rubber to keep me on the road. “Well, there were a couple of tense moments, maybe.” I described the experience.

“I’m not really sure why I didn’t lose it,” I concluded, “but after sliding around that curve, everything became eerie and surreal — as if I had died and moved on to some kind of cyclists’ heaven. I had about twenty more miles of easy downhill, and a misty full moon rose over that ridge across the Crystal River. I thought about stopping in Redstone, but I didn’t want to shatter the mood. I was almost sorry when I hit Carbondale.”

He peered at me with a grin. “Ah, if you keep talking like that I’ll sell this shop tomorrow and join you.”

Actually, Steve was already a veteran of long-distance cycling — he had spent two years riding around the world with his wife of the day. With mathematics degrees from MIT and the University of Chicago, five years of teaching experience, and a stable Maryland home, he suddenly thought, “Hey, if other people can do it, so can I. The only hard part is the first step.”

So off they went, through Europe, Greece, the Middle East, India, Burma, Thailand, Malaysia, Australia, Tahiti, and finally America. I was enchanted, quizzing him about the language barrier (not serious), the impact on their marriage (the only trouble was in Egypt), and how they handled unknowns far greater than those I was facing.

“So much of the world seems dangerous,” I said, sensing that I sounded as provincial to him as most people sound to me. But I went on anyway: “I mean, cycling the Middle East? India? Burma? Asia?”

“We were warned constantly,” he replied, “always about the next place down the road. In Java, they told us we would be eaten by tigers — the people there were horrified at the thought of our cycling into the jungle without rifles.”

“Sounds familiar.”

“I’m sure it does. I asked a guy how many people got eaten that year. ‘Oh, ten or twelve at least,’ he said. Then I asked him how many people lived around there and he told me two or three million. Odds like that don’t sound too bad.”

I laughed. “That’s a perfect parallel to conversations I’ve had all over the country. Hell, there’s probably somebody who thinks Carbondale is dangerous.”

“It is,” he joked, eyes wide. “Don’t go out after dark!”

“You know, one of the nicest things I’ve discovered about traveling is that knowledge replaces fear.”

“Now all you have to do is extend that to the rest of your life.”

I spent three days in Carbondale, panicking about article deadlines and trying to get some work done. I drank goat’s milk, did an interview, and even got a haircut, of all things — for ahead lay Aspen. Ya don’t go to Aspen looking like a bum.

If Crested Butte can be said to be a cozy old couch, then Aspen must be one of those living rooms with clear plastic covers on the expensive furniture, a drop cloth on the white carpet, and a dust cover on the lampshade. It’s beautiful, and they want to keep it that way.

If you ain’t rich, go away.

Actually, such a sentiment is never openly expressed, but it shows up in countless ways. The women (always a favorite subject of mine, if you haven’t noticed) don’t have the muscled hairy legs of Crested Beauties — they have pantyhose, displayed to full advantage under short or slit skirts. They don’t glow with animal grace, but they radiate the carefully polished sexuality that befits an on-the-make town. And they don’t own mountain bikes, they own boutiques.

It’s a much harder society to penetrate.

I met a traveler on the mall, an outdoor place of cobblestones and trees, tourists and strollers, shops and fountains. We chatted of the cycle-touring life, and then a woman walked by in the breeze, the slit in her creamy silk skirt flashing high-class thigh, the perfection of her features a fashion-plate fantasy. She was unbelievable, so sexy that I felt deep pain in my chest. Conversation stumbled to a halt, and I smiled when her eyes scanned me.

No reaction.

I almost commented, but he spoke first. “You know, Steve, every time I come here I get offended. I love it in one way — the girl-watching is incredible and this mall is what God would do if He had the money. But if you smile at a girl, she looks right through you.”

“I noticed. They seem jaded. They look at my bike, but never into my eyes. This is like a marriage of Crested Butte and New York City.”

“Welcome to the land of Big Money.”

Indeed. In a town where women are routinely offered Dom Perignon, nose candy, and Learjet flights to Paris, on-the-street friendliness is a rare phenomenon. I kept recalling a Brautigan poem called “Quail,” a snippet about the caged birds next door and the singing that was the melodic delight of their mornings. “But at night they drive our God-damn cat Jake crazy. They run around the cage like pinballs as he stands out there, smelling their asses through the wire.”

Aspen fulfilled the predictions of all who spoke of it, both positively and negatively. It’s crawling with the stars and the wealthy, skiers and ruggers, tourists and transients. My bike was a foolproof drawing card in a place like this, and I was so flooded with questions that I began to ponder a plastic laminated question-and-answer sheet that I could affix to the fairing.

Breakfast: an outdoor cafe on the mall. Across the way, the sights and sounds of a leotard-clad exercise class poured from an open second-story

window. A crowd of visiting ruggers in matching green jerseys rumbled hairily by. Joggers bounced in designer jogwear. And the motley tourists strolled rubbernecking, gawking, snapping snapshots and interrupting me at my table again and again…

“Is that comfortable? How do you balance it? Is it better than a regular bike? With those solar panels, you still have to pedal as much? Hey, are you the guy who was in the paper? Can it go up hills? Uh, mind my asking how much a rig like that costs? How fast does it go? Do you type while you’re riding? What are the solar panels for, if they don’t run the wheels? Why is the front wheel small? Does that little windshield help? Do you ride on the highways? Isn’t it uncomfortable, having your hands down like that? How far are you going? How many people ride that? Where did you buy it? Does that need a license? Where do you sit? Do you ride at night? What’s the computer for, figuring your distance? Do you camp out mostly? What’s this? What’s that?”

ARGH!!! LEAVE ME ALONE!

Rolling again. A house on Main Street has its own observatory. John Denver’s home on a hillside west of town is a local landmark. Music festival concerts are sixty dollars a seat. The best-known bike shop is an elitist and snobbish place, so I buy inferior shoes elsewhere to avoid dealing with them. Installing a fuel-bottle cage on the sidewalk draws a crowd of over twenty people.

Aspen is a place of spectacular beauty, with obvious allure and lots of exceptional people, but it made me homesick for Crested Butte.

Exceptional people, oh yes. They’re here, alright. Despite the pretention, Aspen is high-energy, crazy, and fun. And very expensive.

I visited a restaurant called “Gordon & Grimsley’s,” which was then in its third month of purveying what it calls “high-altitude cuisine.” It is a place of light but tasteful decoration and relaxed service, a place classy and expensive but decidedly less affected than the other multi-starred restaurants in town. G&G’s had already become a regular haunt of Hunter Thompson (somersaults on the floor), Jimmy Buffet (regular lunches), Judy Collins (thirteen nights in a row), John and Annie Denver (separate tables), Jack Nicholson, Jill St. John and others.

But what really sets it apart is not the client list but the owners’ obsession with quality: from daily shipments of fresh international esoterica to the impassioned delicacy of Gordon’s cooking, every diner is treated to an experience of sensory delight (without the stuffiness found in most beaneries of the rich). The menu changes daily, composed on the word-processor each afternoon to reflect the availability of ingredients. The computer also manages the timing of each meal, handles the wine list, and performs traditional restaurant computer tasks.

“It’s not high-tech to the point of robbing the place of personality,” Gordon said in obvious understatement. “I can beg, borrow, and steal from all cultures — I work with the finest ingredients in the world. It just wouldn’t be fun for me to be involved with those other types of foods.” His conversation reflects a deep passion for his work; his hands move animatedly as he describes flavors bordering on the magical.

For Gordon, this is play — a daily adventure in cooking. There is no freezer on the premises except a small one for sorbets, and the resulting variety keeps both the chef and the customers interested. That evening’s salad was based on exotic baby lettuces, topped with shitake, morelles, and local chanterelles sauteed in walnut oil and champagne vinegar, then sprinkled with roasted pine nuts. The Ahi-carpaccio was made with bluefin tuna pounded thin and cooked with olive oil, aged parmesan, and truffles. One of the desserts was the “Heath bar,” a flour-less white chocolate and praline cake topped with raspberries picked the day before in Chile.

Gordon & Grimsley’s was a treat, a reassurance, a glimpse past the thick shell that isolates the Aspen community from Aspen transients. I sensed the playground, the kind of culture that can afford quality. Few cities of this size would support a restaurant that insists on the best of everything.

But to a significant percentage of Aspen’s population, money is no object. That’s bound to have some interesting effects.

Aspen is a place of events — from music and film festivals to bicycle races to the tennis open.

And then there’s rugby. A ruggerfest was in progress: violent men with the demeanor of warriors were breaking each other’s bones in a game incomprehensible while fans, teammates, and photographers cheered them on. I watched in amazement, struggling to figure out the rules, jumping back in real alarm when a mass of growling manflesh roiled over the sidelines in hot pursuit of the leather ball.

Beside me was a tall beauty in her early twenties: blonde, upturned nose, wide mouth, yummy, denim miniskirt. I smiled.

She smiled back.

I did a double-take. “You… you don’t live here!” I stuttered.

“How did you know that?”

“You looked into my eyes and smiled.”

She smiled again. Ahhh.

We made friends quickly — she had come for the day from Boulder to watch those wonderful big brutes battle it out. I proposed a lap ride. Flustered, embarrassed, and blushing, she climbed sweetly aboard, the crowd slowly turning its attention away from the match, cameras snapping, the green sweater soft in my face, my hand pulling her close, warm fragrance rising around me, her voice soft in my ear, the pedal motion smoothly bouncing, bouncing…

People stumbled, walked into cars, and dropped things. Nobody watched the rugby match anymore; some of the ruggers even stood gaping at us as the battle raged on behind them as coaches shouted curses.

So there, Aspen.

And then she had to return to Boulder almost immediately to make it to work on time.

We met on the mall. Ellen was in her late thirties, bright, quick-witted, single, living with her teenage daughter, and fairly hopping with energy. “Oh, I was hoping I’d get a chance to talk to you! Do you need a place to stay?”

Yes, yes, yes, oh yes.

She was the perfect hostess. Her conversation sizzled, ranging from film to computers. She set up a desk for me and cooked dinner. And as a “welcome to my home” gift, she called in a professional masseuse who treated me to an hour of shiatzu and deep massage, skilled hands gliding fragrant in almond oil, seeking and relieving my tensions with exquisite finesse.

Ahhh. A home in Aspen at last. That night after a photo session I flew in the dark down Independence Pass with good brakes and secure wheel bearings, cruising through the sparkling glitter of nighttime Aspen. In the once-elegant Hotel Jerome I shared mutual enchantment with an entrepreneurial spark-mate; on the brightly lit streets I chatted with the stars of the city’s night life, just twinkling on at nine o’clock.

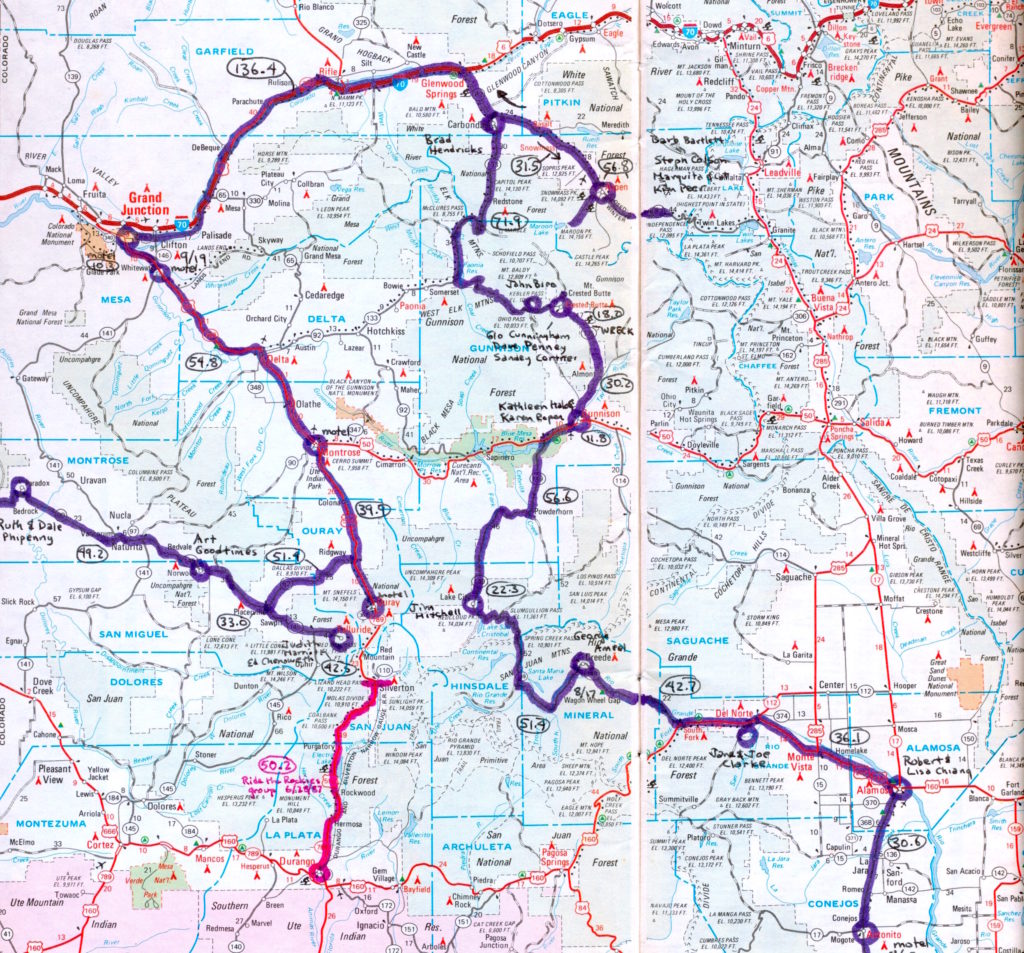

And then it was time. Strangely energized, I arose pre-dawn and left Aspen, downwind and downhill. It was the longest day of the trip: I rode through Silt, Antlers, Rifle, and Parachute to find myself in Grand Junction after 136.4 miles.

Evening. I stopped at a gas station and bought a city map. As I puzzled over it, three old women from Memphis pulled up in a lime-green Cadillac.

“Where am I?” I asked, pointing at the map and gesturing around.

One bustled over to the car, rummaged around in the clutter of the front seat, and returned proudly with a map of the United States. “You’re in Grand Junction, Colorado!” she exclaimed, pointing to a dot with a gaudily painted claw.

“Don’t go to Utah,” another said. “We went there and turned around. There’s nothing there at all.”

“Now we’re going east,” added the third from somewhere inside a perfumed haze of cigarette smoke.

Morning. The headwind was murderous, and it was suddenly a whole different Colorado. Dry, rocky scrub. Stocky little cedars scattered at odd intervals across empty miles. Mesas layered from deep red to sandy brown. And the wind, a brutal enemy, slamming me full in the face after a hundred-mile running start.

I made it ten miles by noon and stopped when I saw the Lazy S Arrow Motel in Whitewater. The next town was thirty-one miles further into the wind.

I entered the round homebuilt two-story log building to find seventy-year-old Dick Sherwood. His front teeth were all gold, and we swapped business cards as he explained the weather.

His card said LOVEABLE RATES. “What do you charge for a room?” I asked.

“Oh, we don’t. You just look it over and pay what you think it’s worth.” Sure enough, he showed me a room and said he would provide a table for me to work on. Back in the office he asked, “Well, what do you want to give for it?”

I hemmed and hawed and finally gave him $15 plus tax. “What do you average?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Most people are honest, you know — what they pay depends on what they’re used to. If they’ve been staying at Holiday Inns, they pay one thing — if they’re used to Motel 6, they pay something else. If a guy’s really down on his luck, well, that’s OK too.” He quoted something from the Bible and went on: “I’m just doing a public service. My only real expense is the maids. I couldn’t make up a bed if my life depended on it.”

I moved in and fell heavily asleep for three hours, waking to an angry sky, lightning, and still more wind. Twinkies and a microwave burrito comprised dinner, and within the hour my insides were rumbling and complaining like the thunder that shook the mesa.

Sick. Big time. During a break in peristalsis I attached headphones to my brain and staggered weakly into the night. Grover Washington’s Winelight filled my head; the sky danced with lighting that cast cloud and desert alike into sharp relief. The soft fuzzy mass of a peach, picked that day on Orchard Mesa, was wet in one hand. With the other I began urinating, the sound a crackle on the rocky earth.

Suddenly a massive white dog exploded in violent barking, straining at a heavy chain, his slavering fangs only inches from my leg. The sound was terrifying; the animal flickering ghostly in the lightning and tinged with cyclic pink by the neon MOTEL sign flashing on the highway. I interrupted the flow with heart-pounding panic and leapt back, retreating from the bare circle of dirt around the doghouse.

The sax played on. Friends seemed far, far away. Suburbia was starting to sound a lot like heaven.

You must be logged in to post a comment.