A Timeless Anniversary

Computing Across America, chapter 43

by Steven K. Roberts

Telluride, Colorado

September 28, 1984

You don’t need big words; you need big eyes…

Judith of Telluride

It was a time of reflection and change. I stopped in Telluride as a punch-drunk quarterback might stumble to the sidelines — watching dazed from the bench as the fray continues. The journey’s first anniversary was three days away.

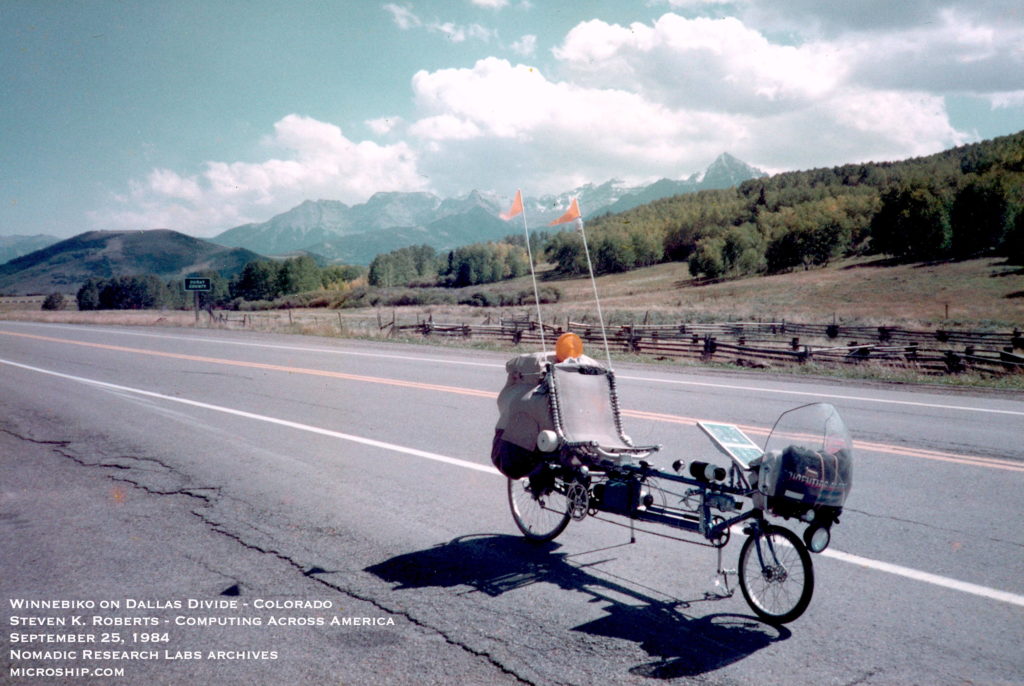

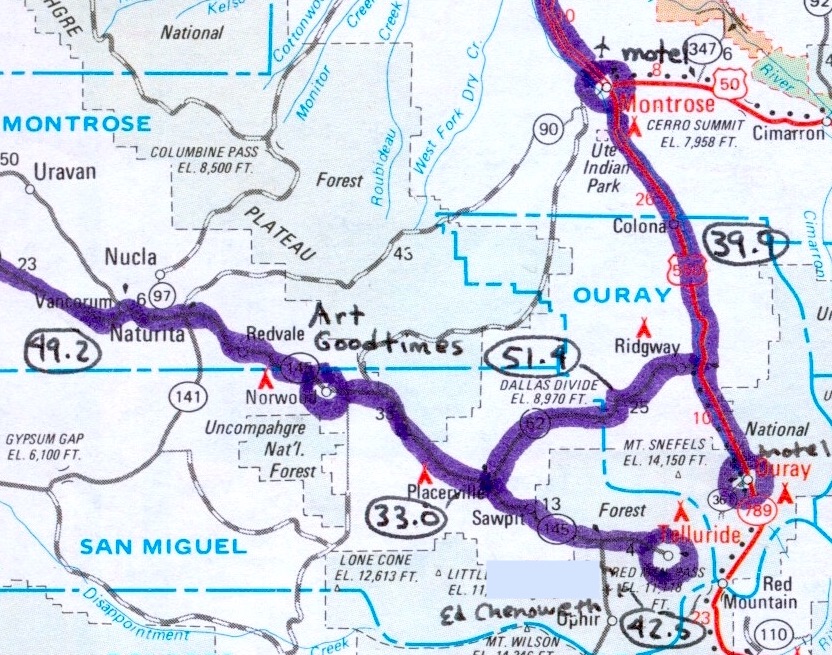

It was the exhaustion that did it. Despite a pace so leisurely that I had averaged only 20.19 miles per day since my departure from Columbus, I was tired, burned out, hollow. Enroute to Telluride I crunched my knee, fought headwinds across endless emptiness, and donned my rainsuit in drizzle only to remove it moments later in sun. I was almost hit by a car near Ridgeway, and my enthusiasm was rapidly boiling off into the vacuum of loneliness.

Sore knee. Sore brain. Sore heart.

In Ouray, I slept in a motel and breakfasted at the Copper Still: yawning through a nothing omelette of raw onions and pale nacho sauce while being watched by a parade of gawkers and flies. The town was beautiful… but sometimes being on the road is a pain. The relationship between audience and show is too shallow.

My bike opens many doors, but they usually turn out to be closets.

Hey, but it was September 25. Happy birthday to me. Weak, I aimed myself at Telluride — no particular reason, no particular plans. I heard it was nice. I wanted to rest, to escape questions for awhile, maybe even find a place to stay. I wanted to get snowed in; I wanted to lie in front of a fireplace and wash in a shower so familiar that I could set the temperature by the position of the knobs. The miles behind me were blurred and meaningless — I had to look at the map to remember the previous two days.

Dallas Divide. One last pass. It was a respectable climb — into a headwind. I was now back in the real mountains and tried to appreciate the beauty unfolding like new love around me, but I was too preoccupied with misery. I plodded my machine higher and higher, sick of the same old tapes, watching the little electronic numbers on the Cat-Eye increment with the slow passage of time.

Passes usually reward effort with bliss, but coming down I complained all the way, coasting into the wind at 20 mph and pissed because I couldn’t go 40. Yeah, it was time to stop alright. In Placerville, I turned east to Telluride — a little seventeen-mile run that paralleled a river and looked flat on the map. But it was headwind again. I fought along, yelling curses at my invisible assailant, a monster determined to blow me back to the bottom of some valley from which I could never emerge.

(I wonder where I would end up if I made a practice of always riding downwind, no matter where it took me? The book of such a journey would become an optimist manifesto: Grinning Across America.)

Then the climb started. Another whole pass, not on the map, a thing called Keystone of some 9,000 feet. The dazzling golden aspens and deep valley to my right were of little delight against the sense of reaching physical and emotional limits. The sight of tiny cars picking their way along the mountainside above wasn’t just humbling, it was devastating.

Why on earth am I doing this?

And so I came to Telluride. First impressions: Lots of construction. Not as laid back as the Butte nor as slick as Aspen. Rednecks and gentlefolk coexisting in mutual acceptance. Smiles from strangers frequent; people easy to meet. After a few on-the-street chats I stopped at the Floradora for dinner.

“Mah lawng hair don’t hide mah red neck,” sang a tall tattoed blonde guy. He and another construction worker joined me, yielding the first of many orthogonal views of this town.

“I’m gonna do a backpacker story for Geographic some day,” one told me, the dust of the day’s drywall covering him like a layer of impossible dreams. “They eat that stuff up, man.”

Cruise mode. Darkness falling, exhaustion like a mugger weakening me. I felt like a bum, hustling a place to sleep. People were friendly but closed, and I sensed a common thread — all over town there was a willingness to chat but no offer of hospitality. Odd…

In front of the Floradora I went through the show-and-tell with a couple of guys, reduced to the level of dropping little hints. No luck. They bid me goodnight and strolled down the street. I sighed and refastened my helmet.

But a tall, thin, longhaired rock musician had been listening from the doorway, and he stepped toward me. “Need a place to stay?”

“Ah, yes, matter of fact I do.”

“Man, I can’t believe those guys didn’t offer. What an opportunity! You’re more than welcome to stay at my place.”

In Ed’s warm, tattered little house with piano, recording studio, and oil-drum-turned-woodstove I began my five-week stay in Telluride.

One year on the road, one year on a bicycle. A year homeless, a year of uncertainty, a year of learning. I lay alone in the living room, snug in a layer of North Face goose down, a cat purring softly on my belly. I stroked her absently, remembering my cat, Monsieur Le Roi du Foret, “M” for short, killed by a car a few days before my departure. He had darted beneath the wheels as if he had known it was over — as if he had realized in feline despair that his world was evaporating and saw no alternative but to end it.

I remember the shock of death, the slowly glazing eyes, my own tears. I pulled Ed’s cat up to my face and breathed into her fur, warm and alive. Her purrs made micropuffs in the cold morning air.

One year. In a little western-Colorado town, I arose and lit the wood stove. My host was on a gig in Utah and I puttered around the house alone, lazy, still exhausted. As always, the list of things to do haunted me, but the PR hustle seemed futile, the USA Today column intimidating, this book project overwhelming.

A walk. Yes, a walk. The sun was breaking over mountains covered in fresh snow, the ghostly houses on the hillside just visible through morning mist in quaint Victorian charm. At 8,745 feet, we were in the clouds, and they cruised slowly around town, stopping to recline in the folds of hills like the lazy spirits of friendly dragons.

I joined them, strolling the streets with the morning throng. Faces were rosy; the down vests and Patagonia jackets lending a cozy touch to a place hazy with the smell of woodstoves. On a mountain to the south I could see the ski runs, marked by plumes of smoke as the seasonal clearing progressed. There were big investment dollars up there, fueling a classic controversy between developers and residents.

A year. I sat on the railing in front of Baked in Telluride, breathing the fragrant steam from a styrofoam coffeecup sticky in my donut hand. Reverie was irresistible. It had been a year of brief affairs, of sweet ephemera flaring in erotic delight and joining the other fond memories of my nomadic life. A year of adventures, surprises and discoveries, new friends physical and electronic, exhaustion and exhilaration, media attention, endless explanation, good food and bad, moments of pure terror, and a sort of underlying madness holding it all together like the paper of this book.

7,370 miles — between two and three million pedal cranks, depending on the amount of coasting.

Not a bad tally for my thirty-first year, but the attempt to wax rhapsodic fell flat somehow. This was no longer a curiosity — I did all my gee-whizzing in the first few months of the journey and now just accepted it as the norm. Of course I live on a bicycle; yeah, yeah, this is a portable computer — it’s my link with the universe. How can anybody live without one? How can anybody ride a regular bike? What, you’ve been in the same place for eight years?

The travel itself had become a backdrop for something else — the road was my equivalent of living room walls.

A year. I sat and watched Telluride happen as it daily does: people checking the “free box” for the latest treasures, people chatting, biking, itching for ski season, and exclaiming at the blaze of autumn aspens. It’s a rougher place than Crested Butte, and some of the faces are hardened by attitudes that mark them as transient labor. But the sense of “home” is unmistakable, the allure obvious in every upward glance at the horizon.

I drained the coffee and grinned suddenly. I was getting paid for this, eh? Alright then, time to get to work.

I packed the yellow daypack. Basic essentials only: computer, water bottle, camera, GORP, jacket, towel. I set out on foot into the mountains, accompanied by somebody’s dog… walking along Bear Creek and looking down on Telluride through the sparse yellow filter of young aspens. The scene danced with bright detail, alive in every pixel like a Richard Dadd painting.

One year. I walked along the dirt road higher and deeper into the mountains, sensing the calm but somehow intent on something — a rumored waterfall, a mine, a place to work, a clearing, the end of the road. I was already “there,” of course, but I strode on deliberately as if habitually enroute.

Suddenly I stopped to look around.

I blinked and sat down on a profoundly uncomfortable rock.

Incredible.

The canyon was in layers, like some kind of cosmic torte, the range of textures dizzying, the beauty painful. I took off the pack. Aspens fell away down the sunny valley, great splashes of gold that appeared to glow from within — alive with a shimmering radiance that belied their slow slide into winter dormancy.

The colors overwhelmed; they moved me. I sat surrounded by pure grandeur on a very, very large scale. Directly across the creek was a vertical slope of pines, interspersed by yellow-green-brown shrubbery. As I looked higher they gave way gradually to rock, in layers of delicious dessert-colors that defied any sane attempt at description. Higher still were the rugged peaks themselves, snow in every crevice, sparkles in every shadowy pocket.

A snow tunnel blazed white against surroundings of everything but white, expelling from its black core a glittering rivulet that danced like an animated thread to the stream rushing below.

Hands shaking, I pulled out the computer and opened a file, then sat helpless at the keyboard with the machine resting on my lap like an executive jet that had just made an emergency landing in New Guinea. It seemed absurd. How could I marshal powers of description when comprehension itself was overwhelmed?

So I pulled out the camera and then looked at it, embarrassed. A camera. Right. Even though this was some of the most concentrated beauty of the entire journey, I couldn’t bring myself to wrap a little frame around it and write “Southwest Colorado” on the back.

It’s quite possible to caricature beauty, of course, and there are photographers, artists, writers and musicians who do an impressive job of plucking people from their environs and dropping them into the middle of fantasy, but still — there’s nothing like relaxing and letting perceptions have their way. There is nothing like wonder.

I put away the hardware, for it had begun to seem a bit presumptuous. I sat, wandered, sat, climbed, and sat some more. But mostly I just looked.

My brain couldn’t even hold it all.

Silent, humbled and thirsty, I staggered into the Last Dollar Saloon and began with a Coors. The place was cacophonous with voices elevated above rock music, accompanied by the standard bar obbligato of clinks, laughs, billiards, and door slams. The air was hazy with smoke; through it I watched tight denim-clad bottoms, rough construction workers (a T-shirt: “It takes STUDS to build houses”), and small groups gathered around the mug-and-bottle litter of small tables. Six o’clock.

Tourists passed the windows and peered in nervously, stepping around mountain bikes and a shaggy white dog. The animal looked up each time the door opened, wagged his tail briefly, then resumed the vigil. I knew the feeling: I was waiting for Glo to arrive from Crested Butte.

The ceiling fan turned slowly. Stone fireplace, antlers over the mantle. Buck knives in leather belt-cases. A Coors dartboard. Budweiser lamps and the usual behind-the-bar motif. A blue bug-killer and a yellowed, embossed-tin ceiling.

I switched to Anchor Porter (the Coors was for thirst; this was for taste) and sat alone in the corner, sipping slowly, recalling in the flavor my brief childhood stab at horehound drops. I had hidden the bag in my bedroom, only to discover in dismay that it was quite unlike candy. But I was so committed to the clandestine act that I ate them all anyway, each one a little penance for my illicit behavior. This thick beer had the flavor of things forbidden, dark and potent — I sipped slowly through the foam and grew as hazy as the air around me.

Ah, Glo. Hugs. Sushi of fresh salmon in the home of a new Telluride friend. Sashimi, rice, and saké, too much saké. A year! A celebratory soap opera, a triangle of lust. Jim jeeped over the mountains from Lake City to lie on the floor and watch bemused. More saké, a fog of memory, pink pajamas, cotton, warm. Thoughts of Ohio spawning like the sushi salmon once had, but washing down a river of saké in confusion. I live here. No, I live on a bicycle. What? The room swirled.

And then a head-spinning careen off to uneasy queasy sleep, Pete Sinfield music whirling with my dizzy awareness into a sick abyss…

Sun. Squint. A Tylenol day. Glo and I motored along, climbing Lizard Head Pass, disentangling our memories of the night with the hungover clarity of retrospect. My head, my head, but God, the aspens! The road made great sweeping curves through the mountains, the surrounding peaks liberally scattered with snow from vast virgin drifts to powder-mottled scree slopes. The trees filtered the sunlight into all conceivable blends of yellow and green, setting whole fields afire with their brilliance.

The contrasts in texture were many and deep.

Near Trout Lake we began climbing the gravel switchbacks, parking at last near a gate marked PRIVATE PROPERTY to walk softly through the ancient community of deep woods. This was unexpected: grandfather trees, somber beauty and sylvan silence, shiver-chilly in the shade and burning cold in the sun. Trees in eternal repose showed all signs of dissolution — from vague irregularities in the vegetation of the forest floor to the freshly felled, as if only napping.

Up, up, up, and suddenly I was winded. The hangover, the exhaustion, the thin air… my steps grew leaden and I fell behind, at last dropping to the ground in a patch of sunlight to doze.

I heard her call from high above, concerned. My eyes flicked open and in my face was the ecological microcosm known as “under a log” — mosses, grasses, and powdery bluish tubules of lichen rising like miniature science- fiction houseplants. I gazed upon the past and future of all that surrounded me, keenly aware of the cycles of growth and decay, life and death.

I was just passing through.

Oddly, the network reinforced that feeling. A life online is a life outside the strictures of physics — at least the conventional physics that make a country seem big. The network is a village shaped like a map of the world, a place populated by specters and ghosts, travelers in time and space. The physical reality of nodes and satellites is a forgotten substrate, a thing no more in our consciousness than the earth’s mantle.

I live there as much as I live here. Since “here” keeps changing, “there” has become home.

Geography falls apart online. It’s an odd contrast: I am living two dramatically different lives. One is visceral, sweaty, attuned to every hill and headwind. The other is ethereal, intellectual, an electronic interlocking of imagination and communication. I am at once a being of cloud and soil, satellite and bicycle; I can drop a thought from the sky onto Baton Rouge while patting a white samoyed named Fluffer in a snowed-in Telluride house trailer. No problem.

And speaking of the sky…

I took to it when I accepted a speaking engagement at a North Carolina computer show — an act absurd, given the fact that the point of a “talk” is to impart information. Information weighs nothing and moves at the speed of light. It seemed a curious way to deliver words, but I put my whole body on an airplane and flew east.

The flight was confusing, oddly serene. I glided with only a hint of turbulence over passes that had been full afternoon’s projects on the bike. I gazed down on mysteries, the Rockies enchanting at every level of magnification from fractal patterns of jagged peaks to the surprisingly combed appearance of forested snowy slopes. Rivers glittering through the snow looked like microtomed and magnified sections of something biological; whole basins lay undisturbed by ancient upheavals while corniced ridges told of nearby violence.

And I could sense in the air around me the presence of my network friends, dancing in playful alacrity like gods — somewhere, nowhere, everywhere at once.

Downtown Charlotte was a shock after Telluride. What wasn’t sleek and new was seedy; flashy glass showpieces of urban architecture sprouted from the squalor like new trees from the compost of the past. Quiet old neighborhoods lay in the interstices of franchise strips and bus lines. It was hot and muggy. But the people were friendly, service was gracious, and the time away from my Colorado home was surprisingly undisruptive.

Only the information to my senses had changed, you see. Life on the network continued as before.

I finished my last speech and returned to my room in the Radisson, drained and lusting for a drink.

I reached for the phone… but the network life is an addicting one. I’m always certain that there’s something in my electronic mailbox, that a message is waiting in one of the Special Interest Groups, or that something’s hopping on CB. I couldn’t resist. The room service call could wait.

I signed on.

And, naturally, got drawn in. Two hours later, I was still at it, chatting with MoonBeam, Stoneface, Purple Flasher, Philthy Phred, Tumbleweed, and c h a r l e s. Periodically, I would bitch to the cosmos about my lack of a drink: since I was tying up the phone with the computer I couldn’t call room service.

Stoneface chuckled and said: “You’re busy here, Wordy — I’ll take care of it. What do you want?”

“A Manhattan.”

“Be right back… He winked out, then picked up his telephone in Washington to call my hotel in Charlotte.

A few minutes later he reappeared online. “Your schlocky hotel doesn’t serve room-service cocktails! Can I get you wine or beer?”

“Sure, how about a couple of Dos Equis?”

“OK… be right back…” Again he disappeared, and ten minutes later there was a knock on my door.

Excusing myself from the conversation online, I admitted the pompous waiter, who stepped across the room with two beers in a silver ice bucket. He set his tray on the table, then immediately dropped the butler act. “Wow! What kind of computer is that?“

I started to answer, but he bent to read the screen. At that precise moment, Stoneface reappeared: “You should be receiving two Mexican beers any minute now.”

The waiter drew back in shock and alarm. “How’d it know that? Man, what’s going on here?”

I grinned at him. “Well, these things have come a long way, you know. That message came from all the way from Washington.”

He eyed the machine with deep suspicion. “Yeah, but… Man, I don’t know… Washington? Shit, man!” He backed slowly away from the table, deeply troubled, keeping his eyes on the HP as if it stood for “Hi-tech Python.”

“Man,Washington…”

Then I got my wish. Back in Telluride, the land was blanketed in snow, the makeshift desk at which I wrote the Introduction now but a white bump on a white knoll somewhere up in the mountains. I holed up in the Floradora for an afternoon, writing, the computer ill-lit before me as I grew well-lit through the consumption of coffee and Gran Marnier.

Outside blew fat snowflakes, gathered en masse by a huge aspen-colored bulldozer under the gentle guidance of a dark-haired beauty. The streets were brighter by far than the sky, and the town had the feel of a Christmas living room in old New England. Conversation swirled as people chatted of skiing, the latest politics, KOTO radio and the weekend’s parties.

The guy from the Introduction saw me and shook his head with a knowing smirk. “I told ya ya’d get snowed in, man.”

I just smiled and moved in with Judith.

I carried armloads of wood and kept the stove going.

I learned the positions of the shower knobs.

And with this lady exactly eleven years my senior — this sensual, intelligent blend of playfulness and maturity — I finally rested.

You must be logged in to post a comment.