Computer Whiz on a Bike

Hi-tech nomad interfaces job and journey

Early in the adventure, it was a delight to have the story picked up by this magazine much-loved in the community of touring cyclists. Doors were opening all over, and this was particularly helpful since a huge part of this kind of travel is hospitality. I remember getting invitations from fellow cycling geeks who were fascinated by the intersection between travel and computers…

The piece also included a reprint of my little story about the convict incident in Maryland. The interview took place in January, 1984.

by Karen Missavage

Bicycle USA

July, 1984

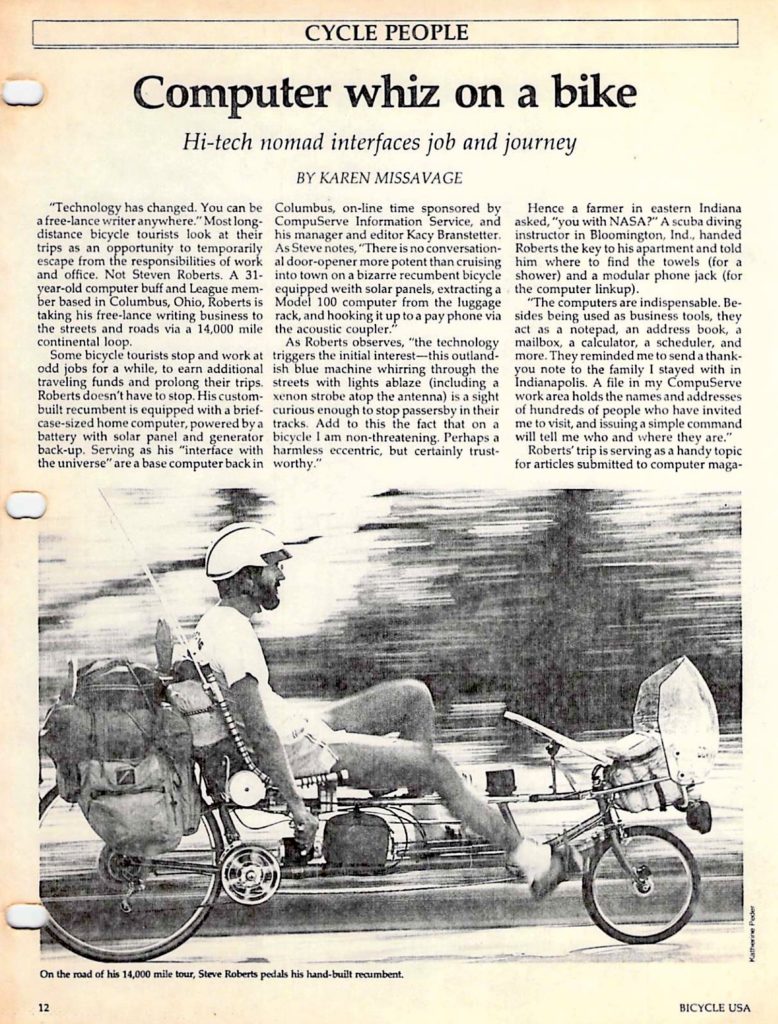

photo by Katherine Peden

“Technology has changed. You can be a free-lance writer anywhere.” Most long distance bicycle tourists look at their trips as an opportunity to temporarily escape from the responsibilities of work and office. Not Steven Roberts. A 31-year-old computer buff and League member based in Columbus, Ohio, Roberts is taking his free-lance writing business to the streets and roads via a 14,000 mile continental loop.

Some bicycle tourists stop and work at odd jobs for a while, to earn additional traveling funds and prolong their trips. Roberts doesn’t have to stop. His custom-built recumbent is equipped with a briefcase-sized home computer, powered by a battery with solar panel and generator back-up. Serving as his “interface with the universe” are a base computer back in Columbus, on-line time sponsored by CompuServe Information Service, and his manager and editor Kacy Branstetter. As Steve notes, “There is no conversational door-opener more potent than cruising into town on a bizarre recumbent bicycle equipped with solar panels, extracting a Model 100 computer from the luggage rack, and hooking it up to a pay phone via the acoustic coupler.”

As Roberts observes, “the technology triggers the initial interest — this outlandish blue machine whirring through the streets with lights ablaze (including a xenon strobe atop the antenna) is a sight curious enough to stop passersby in their tracks. Add to this the fact that on a bicycle I am non-threatening. Perhaps a harmless eccentric, but certainly trustworthy.”

Hence a farmer in eastern Indiana asked, “you with NASA?” A scuba diving instructor in Bloomington, Ind., handed Roberts the key to his apartment and told him where to find the towels (for a shower) and a modular phone jack (for the computer linkup).

“The computers are indispensable. Besides being used as business tools, they act as a notepad, an address book, a mailbox, a calculator, a scheduler, and more. They reminded me to send a thank-you note to the family I stayed with in Indianapolis. A file in my CompuServe work area holds the names and addresses of hundreds of people who have invited me to visit, and issuing a simple command will tell me who and where they are.”

Roberts’ trip is serving as a handy topic for articles submitted to computer magazines, and he is planning to write a book about his adventures. “But the real fascination with this escapade stems not so much from the magic of the technology; instead, it is the fact that someone has actually woven all this into his lifestyle. My ‘Winnebiko’ is not a trade show exhibit or a deliberate attempt to celebrate future technology; it is a functional office-on-a-bicycle, and it works. The computer isn’t just for games; it helps me make a living. The solar panels aren’t just something from a junior science magazine; they are practical tools for day-to-day existence. The camping gear isn’t just for outings; it’s for survival.”

Roberts finished high school at 16, built his own computer at 20, and was a corporate consultant at 21. Apparently this whiz-kid routine had its drudgery. “I have one central conflict that has plagued me all my life, and that’s freedom versus security. This whole trip seems like the optimum tradeoff between the two.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.