The Towpath

Computing Across America, Chapter 11

by Steven K. Roberts

November 6, 1983

Grub first, then ethics.

— Bertolt Brecht

I paused after the long climb on Maryland’s US40 to gaze at the sign and ponder the feelings a driver might experience when deciding whether to “ditch” his truck off the side of a mountain:

ALL TRUCKS STOP

STEEP DOWNGRADE NEXT 9 MILES

THROUGH HEAVILY CONGESTED AREA.

DESCEND IN LOWER GEAR UNTIL NOTIFIED.

IF BRAKES FAIL, DITCH TRUCK IMMEDIATELY.

PROCEED WITH CARE

I gave a light push and coasted on.

At Frostburg College, my dining-hall routine netted an evening of computer-talk and dorm life — the experience as identical to the other colleges as it was different. Staying at a succession of campuses is like listening to Pictures at an Exhibition performed by The Philadelphia Orchestra; Emerson, Lake, and Palmer; and Isao Tomita.

Morning: bright cold sunshine, glittering on the frosty campus. The fall colors were gone on these higher elevations, the trees bare in mid-October. Students enroute to early class puffed along in little huddles, books gripped slippery under nylon parka sleeves.

Over breakfast, my host asked about my route for the day.

“It looks like my only real choice is to stay on US40,” I told him with a shrug of resignation. “I’m not too thrilled about it, but the only alternatives involve worse stuff down in West Virginia.”

“Why — what’s wrong with the towpath?”

“The what?”

“The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal towpath — hell, it’ll take you all the way into the middle of D.C. without climbing a single hill!”

This didn’t seem possible. “A path? Like a hiking trail? Nah, this isn’t much of an off-road bike.”

“I don’t know, man. A lot of people do it on ten-speeds. They call it a hiker-biker trail, or something like that. Check it out — it starts in Cumberland and runs along the Potomac all the way.”

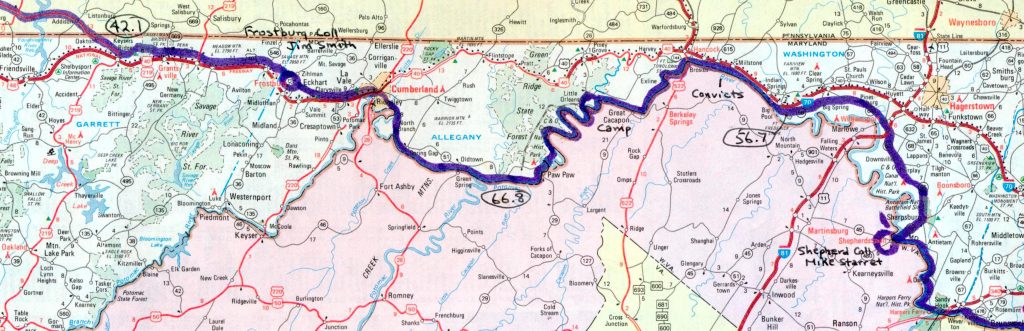

Within the hour, I had ridden gravity the rest of the way to Cumberland, asked around a bit, and wheeled the bike between the posts of a “car filter” to begin riding this historic route — a deep dip into American history. Way back in grade school I heard about this canal — but like everything else it had seemed irrelevant and impossibly remote.

Opened in 1850 after decades of grueling construction and cost overruns, this 184-mile thoroughfare was a key commerce route before being obsoleted by newer freight-handling methods. Until its closure in the 1920’s, it carried coal and other cargo between Cumberland and Washington D.C., making and destroying fortunes in the process. The canal is a masterpiece of hydrological engineering, and elegant lift locks, gates, tunnels, and waste weirs still stand in testimony to the ingenuity of the designers and the sweat of the laborers.

The gravel towpath alongside the canal was for the mules, which pulled the barges through this ruggedly beautiful country. But the canal shut down in 1924 and has since become a national park with campsites offering toilets, drinking water, and firewood.

I removed my helmet and rode into the woods with the rare sense of relaxation that comes from no traffic, no concrete, no neon, and no signs but for little wooden mile markers beside the leaf-strewn path. The going was smooth in most places, though occasional hidden tree roots tossed me off the ground to fall with a fishtailing jolt back into whispering leaves.

I maintained a stable 13 mph through all this, delighting in the sun-mottled fall colors: after the barren branches of Frostburg, I seemed to be turning back the seasonal clock. The Potomac sparkled through the trees to my right, and I was often startled by flashing white tails as deer took flight through the woods. Such sweet relief from the noise and exhaust of the highway — I savored the wind in my hair, the smells of the forest, and the tangible sense of history permeating the place.

After a few hours of this cycling dream, I rode through a 3,000-foot tunnel as spooky as it was picturesque, recalling tales of the feuds and brutal labor that had been involved in its construction. Knocking five miles off the route dictated by the serpentine Potomac, this hole through Paw-Paw hill had become the most legendary feature of the canal. In close blackness pierced only by my headlight and a distant dot of afternoon sun, I saw rope burns on the railing, weep holes on the walls; I strained to hear the echoes of turn-of-the-century mule-drawn barges. Abstract textbook history was taking on dimension.

This was all very stirring, but it was time to seek a place to sleep. I stopped at one of the well-maintained camping areas lying along this cycle-touring bonanza and found that a pedaling couple had already arrived.

I joined them and pitched my tent, creating a high-tech campsite that contrasted visibly with their economy shelter and heavy bikes. We pooled our resources toward the creation of dinner, firing up identical Swedish firebombs to yield a feast of chicken casserole, corn, and more. Then, feeling the ghosts of long-dead barge captains swirling through silent midnight air, I zipped myself in.

I awoke in the mist of morning, the river an unseen whispering presence. Trees floated in the ghostly blanket of fog, and even my own sounds were hushed by the heavy air. Not wanting to wake my neighbors in their barely visible sagging tent, I decided to skip breakfast and hit the trail.

But everything in my life, it seems, now had zippers on it. The complete touring system included roughly ninety-two feet of the stuff, and as I broke camp their sounds knifed cleanly through the soup: sleeping bag zipper, tent door, tent fly, packs, briefcase, jacket. Everything sent out little zizzing signals that slowly penetrated the brain of the snoring camper a few feet away. I heard a stir.

And then a zipper.

I looked over as a shaggy head emerged from the tent and peered about in squinting confusion. “What’s going on out here, man, it sounds like a troop o’ Boy Scouts takin’ a leak!”

On the move. I bid my friends farewell and set out, hungry but energized by the brisk morning. Through heavy forest and open fields, over surprise bridges and deeper into the mountains I went. I saw not a soul, and passed by Hancock enjoying the ride far too much to stop for breakfast. I munched a granola bar and moved on, catching glimpses of I-70 running parallel with the canal between Hancock and Big Pool. There was almost a sense of cheating, so easy was this languid passage through the country I had feared. With every glance at the superhighway through a clearing, I was reminded that all the world is not as idyllic as this quiet path.

I was glad to be where I was.

Suddenly I saw it: the remains of a recent accident. It had been a bad one — a twisted 18-wheeler lay broken in the ditch, its cargo a splat on the hillside. Police lights flashed. The wreckage chilled me, for nobody could easily survive such a disaster: nearby there had been agony or even death, casting a morbid pall over a day of such gentle calm that it could have materialized from a Bambi film.

I stopped, half-curious, half-depressed. I was just taking a swig from my water bottle and reaching for the camera when I heard a rustle in the leaves behind me.

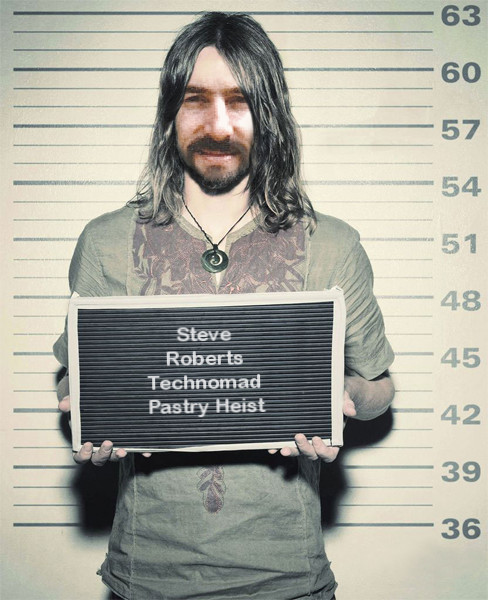

“What the hell’s this?” asked a deep black voice before I could finish turning around. Five men emerged from the forest — five big men, tough-looking and clearly no strangers to violence. Four were black, the fifth a burly redhead. One was clad in black shirt, black pants, and black skullcap, with only a gold tooth to reflect the soft woodland sunlight. The man who had spoken was a giant, matching my six-foot-four height but possessing half again the mass — all muscle.

I grinned uneasily. “Uh… Hi… This is a bicycle. I’m riding across the United States, and it’s kinda like a race, so I gotta go now…”

Gold Tooth interrupted me, his voice an odd mix of curiosity and low menace. “You got a gun on that thing, man?”

“Uh, well, I thought about it, but decided it would just get me in trouble.”

“I heard that,” a third replied. “You don’ wanna be messin’ with no fuckin’ gun, man. Them muthafuckahs get you fifteen years in Maryland, man. Fifteen fuckin’ yeahs.” He grinned savagely and jabbed himself in the chest with a calloused thumb. “Just ask me!“

In the ensuing moment of silence, a bird called out brightly — a high, free sound — a cheerful tweet hidden somewhere in the brilliant autumn foliage.

Of course I had to ask. “So, ah, where you guys from, anyway?”

The redhead guffawed. “Hell, we’re convicts, man, from the Maryland Correctional Institute up at Hagerstown.”

“I see. You escaping, or what?”

He grinned and started to reply, but the giant laid a strong hand on my shoulder and interrupted. “I think we oughta fix our travelin’ man up here, don’t you?”

There were murmurs of assent, and — unable to effectively protest — I set off with them into the woods, glancing back nervously at my exotic bike suddenly all alone on that oh-so-scenic C&O Canal towpath.

We headed toward the highway, then through the trees I saw a yellow truck with an official seal on the door. A lean cop with a shotgun half-dozed on the hood, and some other convicts moved about casually.

“So, uh, you guys a work-release crew?” I asked tentatively.

“You got it, my man. We here to clean up that semi what roll down the hill over there.” We were still walking, not toward the prison truck but into the woods, away from the others and further from the somehow-reassuring cop.

We came to a clearing, safely out of sight of the road. No trucking company officials or police would find us here, and the giant glanced quickly around before leading me to a lumpy mound concealed in the bushes. It was about three feet tall and covered with a musty canvas tarp, and the six of us stood around it for a moment in silence. Another bird tweeted.

In a voice low and conspiratorial, the giant identified the contraband. “Our stash, man,” he said, “the truck was full of this shit.” My eyes widened as he bent to pull back the musty canvas. Now what was I getting into? Would I be living with these guys soon?

With a flourish he whipped the tarp aside. There, right there on the ground before me, close enough to touch, was a huge mound of Sara Lee pastries. There must have been two or three hundred boxes — a sweet-tooth’s dream, a pastry fantasy. A Sara Lee truck? On a day without breakfast? I shook my head and salivated.

The giant bent to pick up a box, then shoved it into my hands. “Have some walnut cake, my man,” he said in a powerful voice. “This shit’s excellent.”

Gold Tooth stepped forward. “Oh man, you don’ wanna be messin’ with no goddamn walnut cake. You want cheese danish, man, cheese danish — that’s where it’s at.” Another box plopped onto the first.

The redhead handed me another. “Hey, you want some of these apple things, buddy?”

And so the pile in my arms grew — as I stood in the Maryland woods with prison inmates who began arguing over the relative merits of various pastries. “How can you eat that shit?” said one to another. “Check these out, man, there ain’t even no compar’son.” The food had thawed since the wreck, and beads of moisture covered the supermarket-bright boxes in my arms. A brown maple leaf clung to a package of pecan coffee cake.

Trying to contain a crazy laugh that was fighting to escape, I said, “Wait a minute, I’m on a bicycle! I can’t carry all this!”

“Let’s go,” said the giant.

So back we went to the towpath — back to the bike standing untouched at the center of a small circle of convicts. They laughed at our approach. “Hey, the dude got him a stash o’ Sara Lee, man! Yeah, check it out! Mo’fo’ be ridin’ two thousan’ miles on that!” They plucked the pile of boxes out of my arms and squeezed them under bungee cords, behind the seat, between the packs, everywhere.

I started struggling with a box of apple danish, at last securing it under a bungee cord. The giant grabbed the walnut cake. “Gimme that!” He stuffed it between the fairing and the electronics package on the front of the machine. “Don’t worry, it’ll stay.”

We said our goodbyes, with elaborate three-stage handshakes all around. I was slapped on the back, given the thumbs-up sign, and wished luck. And as I rolled along the towpath once again, festooned with pastries, I looked for all the world like a bizarre commercial for Sara Lee.

“I’ve already met a lot of strange people on this trip,” I mused, munching cheese danish through a sunny clearing. “But so far, the convicts take the cake.”

Back in 1983, someone gave me a Towpath guide (Hahn) that now appears to be out of print, but this one is well-liked (clicking the cover image takes you to the book’s page on Amazon):

By the way, I pitched this tale to the Sara Lee corporation way back when, thinking it would make an awesome commercial. “Nobody doesn’t like Sara Lee!” They enjoyed it, but were a little wary, I think…

The full text of Computing Across America begins here.

[…] Travel back in time, across (part of) the USA, without leaving your chair: Nomadic Research Labs […]