Education and Technomadics

This relic from the archives is from a time when life on the Internet involved longer attention spans than the social media of 30 years later. On the Technomads listserv, like many others, there were long-running discussions comprised of well-written impassioned commentary by net denizens, and some message threads were like interactive many-to-many magazines.

The piece below is a post I wrote about education. I had returned from the BEHEMOTH jaunt, and was back in the Bikelab at Sun Microsystems, working on the mobile lab.

post to technomads listserv

by Steven K. Roberts

February 15, 1992

Well, well. It’s amazing how a few casual comments can spark such vocal, impassioned, and literate responses! I am now fully convinced that some digesting of this list is justified, with compressed threads posted as articles on the FTP server and in the Nomadness journal (I’ll contact the contributors for permission first, of course).

Anyway, there have been so many well-spoken opinions on this education issue, and it is so germane to the technomadic essence (gak, more jargon…), that instead of quoting and commenting on your various observations I’ll just hold forth for a bit…

First of all, I must say that one of the greatest pleasures of travel is the discovery that there are outposts of brilliance even in the most pathetic of backwaters. Gaussian distributions occur globally, and asymptotes are found in places far from the obvious high-tech or academic subcultures. So anything negative I say about schooling should be taken in its larger perspective — there are people who will excel and invent no matter WHAT their formal educational background… because they know how to either bend it to their own ends, as Brian pointed out, because they can mobilize to address pressing needs, like the Lubbock projects Bob described, or because they can take matters into their own hands, driven by their own desires to learn whatever is required to move into new territory.

Passion and curiosity are better motivators than fear of tests!

I acknowledge the powerful accumulations of resources known as universities, and the dedication and skill of many educators — some of whom, like this list’s Ed Carryer at Stanford, are sensitive to the realities of industry and haven’t faded into rarified academic irrelevance. I also realize that this is a subject that stirs powerful reactionary emotions, some well-reasoned, others rooted in the emotionalism of the alma mater (especially, I just realized, here on the Internet with its strong university population). I have been accused of throwing rocks at the system — hell, I dropped out as a freshman to become an ungineer and independent scholar, so my motives are suspect, right?

To minimize flamage and keep discussion focused, I have tried to distill my comments about the education system Into a few specifics:

1. Existing educational methods are generally motivatlon-insensitive, with the student’s innate desire to learn neutralized in the classroom atmosphere. Fear of failure replaces curiosity. Students discover in the first or second grade that they don’t learn in order to satisfy their questions about the world; they do it to satisfy other people.

2. Typical schools ignore the fundamental mechanism of learning — association. Instead of establishing global contexts and then filling in details, most systems teach unrelated “subjects” and attempt to instill the vague faith that they will all fit together someday. (Quickie self-test: Shelley. Whitman. Wordsworth. Do you smile with memories of insightful poetry, or wince at the memory of high school English and its dreaded paraphrasing, themes, and tests? Insights trapped in the grim straitjacket of “school subject”)

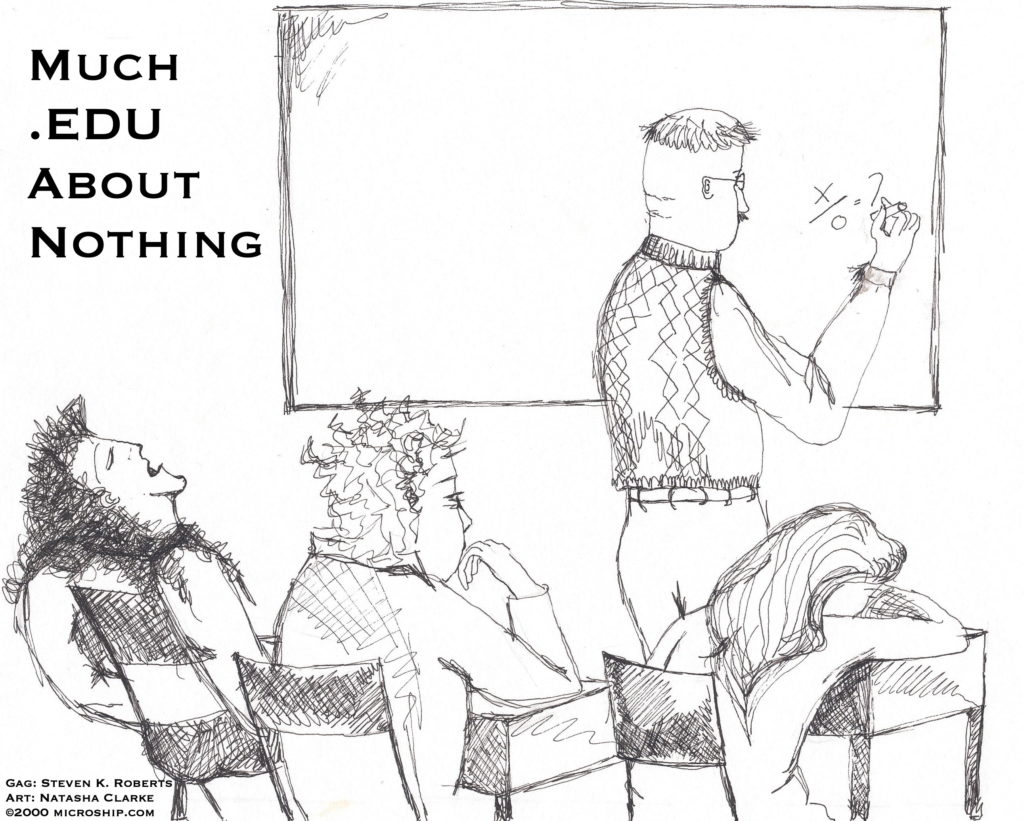

3. Learning is too often a passive affair, typified by the lecture process. This is an efficient method of transferring information from the teacher’s notebook to the student’s notebook without touching either brain in between.

4. Students are rarely able to control pacing. Wrists are slapped for reading ahead, yet children are punished for dozing off in the unstimulatlng torpor of the non-interactive classroom. One study has shown an average of about one minute’s worth of one-to-one student-teacher interaction during a 6-hour school day.

5. Academia has a well-deserved reputation for incestuousness— it is a closed society infrequently updated by real-world information. (Please bear in mind that here on the Internet we are living exceptions— don’t take this personally; look around.) The notion of “global perspective” is often discussed as an abstraction but seldom realized. At a 1982 Stanford conference on “Global Perspectives in Education,” I could find no teachers who had ever considered shortwave radio as an educational tool. I was invited to address a university computer science class about life online and they had scripted a complete simulated “chat” session, which was then executed between two terminals! No spontaneity… no attempt to actually use the information or connect to the world.

5. The learning process is subject to the wit, whim, and skill of individual teachers, who like everyone else cover a vast statistical spectrum. At a Catholic school in Columbus, eighth-graders were asked to draw their conception of God. A friend’s daughter thought hard about this and turned in a blank sheet of paper. She received an F.

6. Testing, even of the standardized sort, is culturally biased and admits no alternative views of the world. I once took a test with a “picture question” in which I was asked to associate images. The first picture was a paint sprayer; the remaining four were a screwdriver, welding torch, pliers, and paint brush. Which is most closely associated with the first? I say the torch, which also accelerates something through a nozzle. The correct answer, however, is the brush.

8. Funding is a function of local demographics. Florida is fading as an educational force — the fast-growing retiree population votes down school levies that divert funds from other programs.

9. The “right-answer” syndrome, already discussed in this thread, is growing rapidly. It makes teaching easy, a sort of crank-turning affair with student performance easily measured. The results are dismal: no imagination, no research beyond doing a text-string grep through the book.

School is not a place of intellectual resources for the curious and alive — it’s a place to forget about your interests and strive to meet a standard. (Isn’t that very notion offensive?) Here we have millions of intelligent little information sponges, entering first grade only to be squeezed dry over a decade or so and molded Into shapes that make good administrative sense. Passions yield to percentiles. Growth is measured in grades. Wit and intuition, those non-numeric attributes of a healthy mind, end up being of little consequence in a system that recognizes only scores.

From all this, you learn that it is more successful to work for approval than to pursue your dreams. You discover that an A is better than an insight. That a promotion is better than an invention. That a stable bottom line is better than risk. And that it’s dangerous to ignore the expectations of people who measure you against what you SHOULD be and punish accordingly.

Whatever the broader problems, societal norms, and expectations, the reality is an educational system that attempts to deal with a highly diverse spread of junior intellects by punishing anything more than one standard deviation away from meanness. It’s convenient and easy to measure, but look at the results! Outside these hallowed networks and high-tech enclaves blanketed In stimulating vapors of silicon (and even within them, alas), we see overspecialization to the point of suicidal tunnel-vision, performance anxiety driven by the dreaded employee evaluation (just like tests…), and discomfort with Heavy Learning Curves. Fear of Failure replaces Joy of Invention. Even corporations take tests in the form of quarterly reports, and managers have no time to consider 5-year plans when things have to look good for the stockholders at next month’s board meeting.

I honestly don’t know whether these educational ills are a product of society, or the reverse. But the cycle must be broken. I urge the following…

1. Identify your passions and integrate them into your work, to the point that excellence is a daily, personal, honest objective. You are more important than your boss’ opinion of you. Grow!

2. Do anything possible to rediscover the joy of learning. Read. Consider time to be well-spent if you learn something, even If the “results” are dismal. Share insights and discoveries with friends and family.

3. Publish. You will not only enjoy spectacular personal and professional benefits, but you will also share your intelligence and knowledge with others.

4. Get to know some kids, beginning with your own. Treat them as intelligent contemporaries, respect their interests, and constantly tease them with intriguing information. They’re naturally curious, and even if this has been suppressed by school, it can be revived. Hobbies that involve the mind must replace the numbing influences of television and Nintendo. Get your kid a Mac and a modem. Turn ’em on to ham radio. Volunteer to talk about whatever you know well— like networking— at local schools.

5. Fight for change in whatever way is effective for you.

6. If you run a company, integrate imagination and generalism into your hiring standards. Crank turners are often necessary, but whole companies built from them will crank themselves straight to oblivion. Create a demand for people who think and invent, no matter what their academic credentials. A degree indicates perseverance and skill in taking tests (or at least the ability to fake it). It is not necessarily correlated with problem-solving ability, invention, wit, insight, awareness, intellectual alacrity, or the context-switching ability indicated by humor.

7. Play. Measure success as the ratio of all you put out to all you get back, not by your financial bottom line. Minimize emphasis on social indicators of success, and throw resources at things that make you grow beyond your present limits. Then propagate this attitude around your organization, throughout your family, and among your friends. It works… slowly, but it works.

Thanks to all who have commented on this subject, which may at first glance appear to diverge pretty far from technomadics. But I believe that the very essence of all this is the blending of diverse skills and technologies to awaken new possibilities for ourselves and society in general, and deeply interwoven with all that is the way we learn.

Time to fix it, eh?

Cheers from the Bikelab,

Steve Roberts