Nomad for the 90s

This piece in the Santa Cruz Sentinel was published during the intense BEHEMOTH epoch, while I was still in the lab at Sun Microsystems.

Anywhere can be home in the age of instant communications

by Peggy R. Townsend

Santa Cruz Sentinel

February 15, 1992

Steven Roberts’ bike stands In a windowless gray office in the bowels of a sprawling office building in Palo Alto.

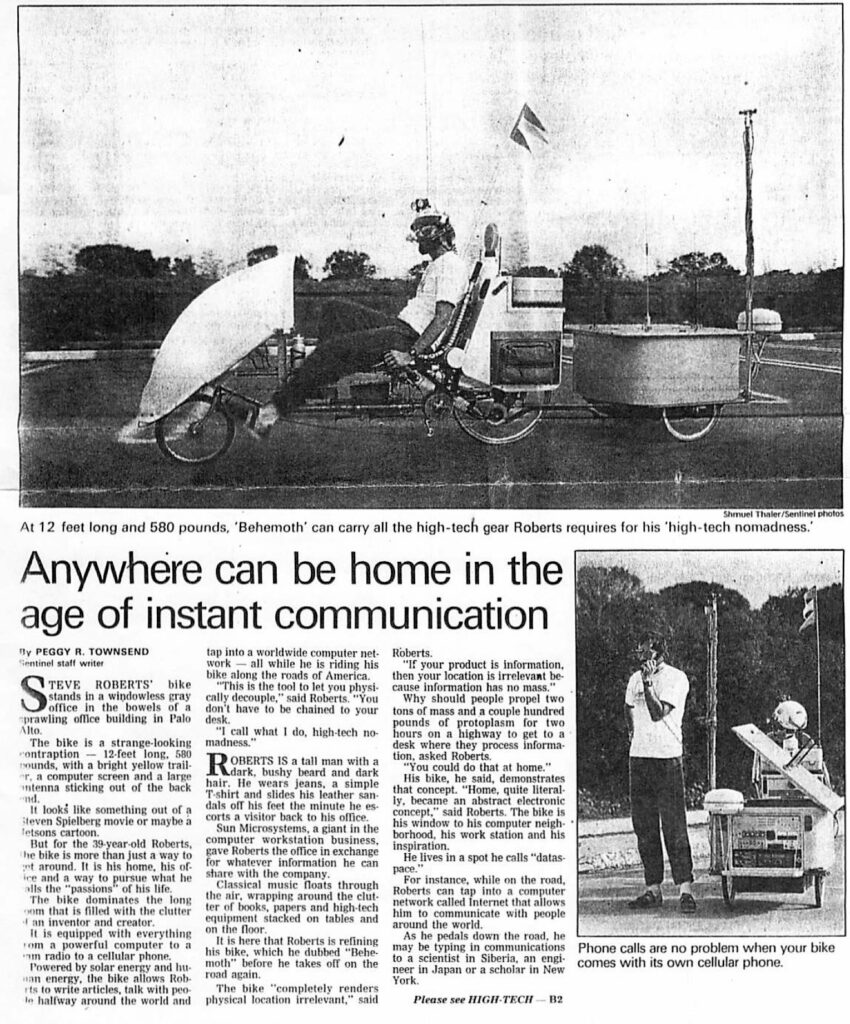

The bike is a strange-looking contraptlon — 12 feet long, 580 pounds, with a bright yellow trailer, a computer screen and a ham antenna sticking out of the back end.

It looks like something out of a Steven Spielberg movie or maybe a Jetsons cartoon.

But for the 39-year-old Roberts, the bike is more than just a way to get around. It is his home, his office, and a way to pursue what he calls the “passions” of his life.

The bike dominates the long room that is filled with the clutter of an inventor and creator.

It is equipped with everything from n powerful computer to a ham radio to a cellular phone. Powered by solar energy and human energy, the bike allows Roberts to write articles, talk with people halfway around the world, and tap into a worldwide computer network — all while he is riding his bike along the roads of America.

“This is the tool to let you physically decouple.” said Roberts. “You don’t have to be chained to your desk.

“I call what I do, high-tech nomadness.”

Roberts is a tall man with a dark, bushy beard and dark hair. He wears jeans, a simple T-shirt, and slides his leather sandals off his feet the minute he escorts a visitor back to his office.

Sun Microsystems, a giant in the computer workstation business, gave Roberts the office in exchange for whatever information he can share with the company.

Classical music floats through the air, wrapping around the clutter of books, papers and high-tech equipment stacked on tables and on the floor.

It is here that Roberts is refining his bike, which he dubbed “BEHEMOTH,” before he takes off on the road again.

The bike “completely renders physical location irrelevant,” said Roberts.

“If your product is information, then your location is irrelevant because information has no mass.”

Why should people propel two tons of mass and a couple hundred pounds of protoplasm for two hours on a highway to get to a desk where they process information?” asked Roberts.

“You could do that at home.”

His bike, he said, demonstrates that concept. “Home, quite literally, became an abstract electronic concept,” said Roberts.” The bike is his window to his computer neighborhood, his workstation and his inspiration.

He lives in a spot he calls “dataspace.”

For instance, while on the road, Roberts can tap into a computer network called Internet that allows him to communicate with people around the world.

As he pedals down the road, he may be typing in communications to a scientist in Siberia, an engineer in Japan or a scholar in New York.

“I have fewer distractions and much more energy,” said Roberts of his work on the road.

And as for the danger of riding and typing information on a computer?

“You can walk and talk at the same time, can’t you?” Roberts asks a visitor rhetorically.

Roberts has been working on the bike for about three years, some of that time while living in a home on Glen Haven Road in Soquel.

The bike is fitted with a helmet that includes a powerful CD system so Roberts can listen to music, sensors that act as a “mouse” for the computer screens in front of him, and a microphone so he can use his ham radio or cellular phone as he rides.

It also has a heads-up display built by Reflection Technology that puts the illusion of a floating computer screen in front of him, so no matter where he looks the “screen” is in view.

Roberts “types” information on to the computer using buttons positioned on the handlebars of his recumbent bicycle. The inspiration for the binary system came as Roberts played his flute one day.

The bike is worth about $1.2 million, said Roberts.

You could say Roberts’ dream began to take shape as a young boy, growing up in Louisville, Ky.

Even as a boy of 8,” my passions were holing myself up in my basement lab and building stuff,” said Roberts.

The son of an artist and adopted by a design engineer, Roberts’ answers to most things were technological in nature, even then, said Roberts. When he thought his parents were talking about him, for instance, he wired the house so he could hear what they were saying and when he got beat up by a couple of bullies at age 12, he retaliated by building a device that administered a shock through two streams of water from squirt guns.

He loved science fairs and things that involved projects, but the boy didn’t like school. “I got the suspicion in grade school, and had it confirmed in college, that in school you didn’t learn to satisfy your curiosity, but you learned to satisfy others.”

Roberts dropped out of college after one year and began to teach himself. He taught himself so well that he was able to write and publish a graduate level textbook on computers and get consulting jobs.

But in 1983, he suddenly realized he hated his life. He had a house in the suburbs, a wife and a job.

“I was working harder and harder trying to pay for things I didn’t want anymore,” said Roberts.

“I was 30 or 31 and all the passion had gone out of my life.”

So Roberts sat down and made a list of things he loved to do — travel, biking, adventure, computer networks, writing — and launched his first project.

His marriage ended, he sold his house and built his first communication bike, called “Winnebiko,” and set off on a 10,000-mile journey across the country, showing that one could work on the road.

Although the bike was primitive compared to his bicycle now (it was equipped with a little Radio Shack Model 100 computer) it brought him in touch with his life and the people of America.

For Roberts the bike “represented the outrageous notion that very soon now, it might not matter where your body happens to be… as long as you maintain a presence in the networks.”

Roberts wrote a book, but outgrew his Winnebiko and began work on his new machine. “BEHEMOTH the megacycle” was born — a bike with state of the art technology, refined and repackaged into the computer-commuter bike.

He became a nomad for the ’90s. Along the way, Roberts has had to deal with the mundane: like how to power 580 pounds up a hill (he designed a system of 105 gears) or how to stop the same 580 pounds from getting up to warp speed on a downhill (three brakes).

He also designed a six-level security system to prevent the bike from being stolen.

One level senses anyone within 10 feet of the bike, another senses if someone touches the bike, and still another tells if anyone is opening an access panel. The bike sends Roberts a signal and then issues a warning using a speech synthesizer — which works just about everywhere but in Silicon Valley where “it is simply regarded as amusing,” said Roberts.

If that doesn’t work, Roberts also can set off an ear-shattering auto burglar alarm.

But if someone gets on the bike and tries to ride it away without first signing on with the proper access code, “all hell breaks loose,” said Roberts.

The bike, which is linked to a satellite 21,000 miles in the air, immediately dials 911 and delivers a call for help. “Hello police, l am a bicycle. I am being stolen. My current latitude is…” says the bike using the satellite to give its exact location.

For Roberts, the bike is about more than technology though. It is a way to break out of the norm, out of the “numbing” aspects of modern-day life and live for his passions.

“That is one of my major themes — living for passion,” said Roberts, settling into a maroon office chair in the middle of his office lab. “The most delicious freedom comes from living beyond the norm.”

“There is no such thing as a passion dilettante,” he said, quoting from an article he wrote.

Roberts hopes someday to form a nomadic community of people, working, writing, entertaining and traveling — all linked by a computer network.

And then, when he’s 65?

He wants to be “someplace beautiful and happy.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.