Fulmar X-19 Delivery

Nomadness Report, Issue #25

by Steven K. Roberts

July 16, 1994

San Diego, California

“Water corrodes; salt water corrodes absolutely.”

— James R Louttit, The New Skipper’s Bowditch

Hi. Remember me? It’s been almost 8 months since a Nomadness Report. While some might construe this as a lack of activity, it’s anything but: since the last posting, I’ve driven to Seattle to pick up the boat, sailed in the Gulf Islands of Canada (and elsewhere enroute south), seen extensive development in over a dozen student projects, and worked with a dedicated team to haul the boat up the side of the building and into the lab. The Microship is here. At last.

Fulmar X-19 Delivery

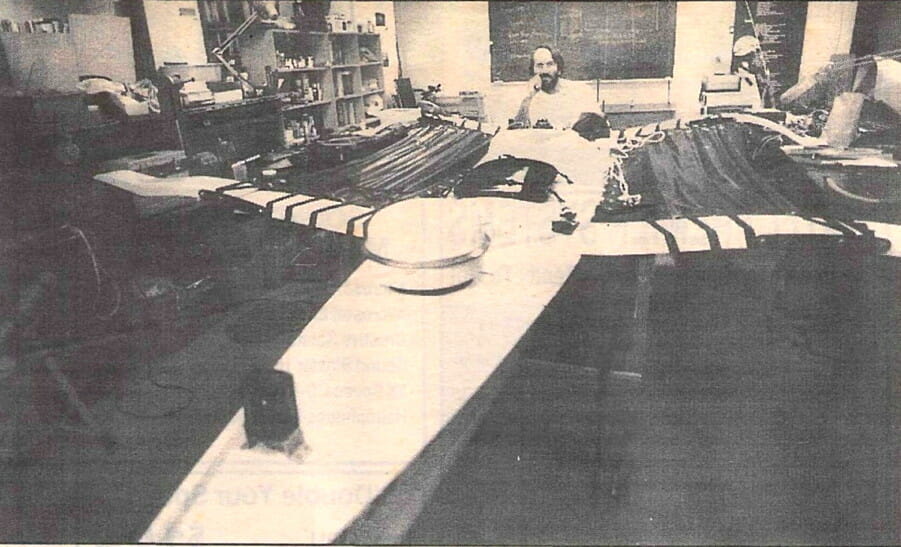

Yes, the Microship is here… and it’s not going anywhere for a while. The adventure of moving it into the building is not one I’ll want to frequently repeat. It had the character of a commando raid with mountain-climbing overtones — Seth and Samer shouldering massive davits and 420′ coils of rope, climbing in the dusk to the 4th floor followed by Jeremy with a block & tackle extension weight and me traipsing along with the video camera. It was insane: clamping the davits to the 4th-floor balcony to form a sort of crane, fighting in the gathering gloom with tangled, twisted lines while gazing down at the Microship-to-be, incongruous behind my parking-ticketed truck in the glare of sodium-vapor lights. And then at last, nearing midnight, fueled by nervous excitement, hauling on the lines, 5-part purchase partly offset by 60′ of chafe, inching my blanket-shrouded boat skyward like a marine mammal out if her element, slowly nearing the 3rd-floor. One big heave, over the railing and practically crushing the kayak cart made by Gregg Zahn in Los Osos, at last squeaking through my lab door and <grunt> onto a hastily fabricated workstand.

Here is a 9-minute video of the adventure, including some shots around the lab over the following week or so:

Fulmar-19 arrives at UCSD Microship Lab – 1994 from Steven K Roberts

(Thanks to Seth Ceteras, Ken King, Bob Behnke, Jeremy Heath, Samer Dehaini, Dan Yang, Len Wanger, and Jason Corley for helping turn the lab into the shiplab it was meant to be!)

And so it’s here at last, and the project seems much more real. The idea of zipping out for daysails on pretty Saturdays, however, is wayyy on the back burner… unless we can move to a ground-floor lab…

The nice thing about this is that the project is no longer abstract. No need to sketch vague boatlike oblongs in my notebook… I just go sit in the cockpit and think about packaging. Everything has scale and context. And everything is too big and heavy… the lessons learned from BEHEMOTH are being taken seriously. We’re going to swiss-cheese everything (except the hull).

The adventure of getting the boat here goes much further back than that exciting Friday evening of learning the horrors of unconstrained 3-strand nylon line. I fired up the diesel and drove to Seattle, yawning interminably up I-5, picking up a Shoreland’r trailer from an outfit called Trailer World that had no idea where to send me for trailer wiring. Feeling on the eve of a new epoch, I rumbled into Fulmar’s tiny lot near Shilshole Marina in Ballard.

Within a day, John Sinclair and Richard McKay had my new boat (hull #9) tested, configured, and mounted on the trailer… and almost timidly I set off into rush-hour traffic, acutely conscious of the small fortune exposed on my rear. I took the Kingston Ferry and camped in heavy rain in Port Angeles, then for the horrendous fare of $85 (they do love trailers; the truck alone would have been $29), ferried over to Canada.

For the next three days I hung around Victoria, sailing and exploring. The Cowichan Bay Maritime Festival was the site of the annual pedal-powered boat gathering, and I had a chance to mess about on the water with about 8 other craft — some amazingly swift. I’m convinced this is a whole new genre of human-powered boats… you can pedal twice as fast as you can paddle, and your hands are free for other things:

In 2020, Bob Stuart helped reconstruct my video of this event, and writes: “The opening shot is Greg Holloway, with my 1st “Kawak Drive Unit” in a Valhalla surf ski. The big yellow cat breaks down to airline luggage sizes, and belongs to the Vogels, Jeanette and Werner. The white canoe has Bob Simons, pedaling a model T bevel gear onto a slanted prop shaft with no packing, just a tube above water line.” I think the paddle-wheeler is Mike Lampi, from Seattle.

I set out the next day with Bob Stuart, builder of a commercial pedal-drive unit that can be retrofitted to canoes and kayaks (Kawak Drive, later named the Spinfin). We launched in Victoria and sailed east to beach on Chatham Island, then meandered around the small archipelago of which it is a part — slipping over shallows where big boats can’t go, flying when the breeze kicked up, pedaling in the calms. The Fulmar is an amazingly agile little boat. We decided to swing around to south side of the city, and on a whim headed out into the Strait of Juan de Fuca to loop around Trial Island before heading back. During a long eastward reach we fell into conversation, navigating casually by watching Mount Baker to the east, dead ahead.

“Hey, I thought we were past the island,” I said, looking suddenly portward. Indeed, though we had been sailing east, we seemed to be moving west, and the island we had been skirting was rather surprisingly distant. I recalled hearing about 6-knot currents in the Strait, and we were at the time of maximum ebb. I trimmed the sail and willed the boat forward, then extended the auxiliary drive and began pedaling. A vague unease crept over me… a few hours of this and we’d be bobbing in the Pacific Ocean after dark. To gauge progress, I pulled out the GPS and took a fix, then displayed speed. Heading: 0. Speed: 0.0 knots. Hmmm. We were sailing — and pedaling vigorously — just to stay in one spot.

Of course, the solution was obvious: I turned north and ferry-glided across the current to Victoria, forgetting the plan to make a big loop around the island. The wind was faster through the channel, and the current slower — a long series of intense tacks and some hard pedaling got us around the point and homeward. An interesting lesson…

The third day of Canadian sailing was quite the opposite… dead calm. This time with Matthew Smith of Current Designs on board, I pedaled under bare poles from Sidney to James Island… and he pedaled back. Still idyllic: there’s nothing like whispering to a stop on the sandy shores of an uninhabited island to raise one’s boat to the level of magic carpet.

Every day a different sort of treat… or challenge… or adventure. I’m starting to like this.

Back in the USA, a day in Humboldt Bay presented a whole different flavor. 25 knot winds, gusting above 30. Distracted by a few onlookers, I launched from a lee shore in a narrow channel, intending to pedal out and then unfurl the sail in one smooth dramatic move. But <blush> I forgot to bend on the mainsheet and had left the sail furled backwards after a demo in H-P’s parking lot. This began an amusing (for them) spectacle of pedaling to windward, scrambling forward to work on the sail, jumping back into the cockpit to pedal to windward again before being dashed on the rocks, clambering forward again… finally, after four cycles of this, getting it together and unfurling only to have the sail snap into a tight, wind-whipped belly and ZOOM… flutter… ZOOM… luff… as I passed rows of docked boats in the harbor. The crazy wind finally stabilized as I rounded Indian Island, and I got a good taste of the Fulmar’s performance in intense conditions: FAST. 12 knots plus. I wanted to circumnavigate the island, but the bay turned to mudflats and the sight of breaking waves was not inviting… so I made a pair of 80% circumnavigations instead.

Finally, San Pablo Bay and Petaluma River. Another calm day… lazing about on the tramps, waving at motoring sailboats, pedaling occasionally. Grandiose plans to cross SF Bay to meet Paul Kamen at the Berkeley Yacht Harbor were dashed by the twin snags of his being out of town and the lack of wind, so I turned back, finally enjoying rising wind as I neared the mouth of the river. It KEPT rising, from dead ahead. Soon I was tacking back and forth upriver, the surface wildly choppy, apparent boatspeed amplified by the movement of nearby riverbanks. Suddenly… the mast leaned oddly to port… I sheeted out quickly… and it toppled into the water.

While this did unmistakably improve the view, the unexpected dismasting was a bit of a shock. Fortunately, I was parked only a couple of miles downriver — an easy bit of pedaling — so the situation was not as serious as it would have been during the planned Monterey Bay crossing later in the week. Still, it was distressing, and deserved a bit of research.

It turned out that I was using an experimental ultra-thin carbon-fiber mast — the first ever tried on a Fulmar. The subcontractor was an old hand at carbon but new to masts, and used a straight-gauge 3-ply layup over the full length, not thickening gradually from head to base. The replacement, now complete, is 3 layers at the tip and 7 at the base… so we shouldn’t see a repeat performance. I’m rather glad it happened, actually… the only way to understand the limits of a material is to see it fail. I’m just glad I wasn’t halfway to Catalina Island in a gale…

The rest of the adventure was like any road trip — a couple of flat trailer tires, an accident on 680 at 60 mph (some guy did a double lane change in front of me to make the 24 exit), awesome views along the coast, a few motels, interesting friends, lots of boring Central Valley, and, of course, brake failure on the LA freeways at night (vacuum pump). We wouldn’t want things to go TOO smoothly, now, would we?

Current Project Status

Having the ship perched incongruously in the middle of my lab, hull nestled in formfitted cushions and akas sprawled over carpeted longerons, changes everything. Forget all my previous specification documents. The control network has dropped from 16 distributed nodes to less than half that, only two of them physically remote from the central equipment bay (power manager and video turret). The console has shrunk from a nav station worthy of a megayacht to a rather modest, paged affair — an outer panel carrying essential GUI, depth, time, hub, power, and nav screens… folding down to expose a keyboard and the Mac screen. We’re even repackaging working circuit boards to increase density and reduce demands on scarce real estate. Part of the trick is increased reliance upon multitasking in the FORTH environment, the rest is careful elimination of redundancy wherever it rears its seductive head.

There’s a long way to go, but I’m targeting June, 1995 for initial launch. Between now and then, I’ll be continuing to work with UCSD engineering students (18 last quarter) as well as numerous volunteers and sponsors, trying somehow to bring this complex system online. A shakedown of sorts is planned for September — a 10-day unsupported cruise from Seattle to Port Townsend for the Sea Kayak Symposium, then through the Gulf Islands and the San Juans. This should be a good reality-check for camping and basic survival issues, whereupon boat surgery will begin in earnest as we build the pressurized equipment enclosures, folding solar arrays (Solarex unbacked modules laminated onto 2″ carbon-skinned polypropylene honeycomb), thruster/generator system, antenna platforms, integrated nav/charting/database software, graphic front end remotable via 9600-baud packet link to the manpack, custom seat, water processing system, and so on.

The weight budget for all this is extremely constrained — at the absolute maximum, I have room for about 450 pounds of stuff in addition to my body. Even at that, the boat is likely to become sluggish and hard to haul out, so we need to shave every ounce. This, as I discovered during the BEHEMOTH epoch, is easier said than done… but the motivation is stronger now that I think about a distressing characteristic of water that I’ve noticed: it collects in low places. Everyplace else is uphill.

If the last thing you saw about the Microship was Issue #24 of this series, then you can see how much has changed. At that time, it was to be 30′ long, weigh a couple of tons, carry a copilot, support under-deck sleeping, deploy kayak amas as playboats, and enter road mode on a whim. Now it’s 19′ long, weighs 260 pounds empty, will be a solo craft, supports sleeping in a tent over the solar panels, and folds simply for trailering. The kayaks would have offered excellent flexibility, but various marine architects convinced me that they are exactly the wrong hydrodynamic form for service as trimaran amas. (Hey, interested in a Current Designs Libra double for about half price?) Now that the Microship is a one-person craft, anyone joining me on the water will have to bring their own boat to the party.

Speaking of which, you may know about the technomadic flotilla concept — there’s a small listserv on the microship website for people who are contemplating traveling together in a fleet of human/solar/sail powered networked boats. I have a recent posting about this on the server, but basically I’ve decided that the stresses and complexities of trying to manage a large number of people in boats of varying capabilities would be daunting, and that I should instead travel light but form a “Virtual Technomadic Flotilla.” This is easy, by comparison: it basically means an Internet-based community of people who are fully nomadic, sharing in the production of a magazine and other projects, optionally using the same home-base support facilities. If you are interested in this, send me your ideas and ask me to add you to the flotilla mailing list.

Enough for now. If you want technical details and have Net access, the Web server has the full library of Microship Status Reports and much more besides. I’ll try to be better at keeping up with this series (Yeah, I know, I’ve said that before…), and please let me know if you’d like to get involved in the project. At the moment, I need antenna, analog, and software designers; a local welder versed in light tubular structures; a fabrics guru; a good local glass/epoxy/carbon-fiber artist; a photographer and videographer; a nomadic working partner; and probably a lot of other skills I haven’t thought about yet. It’s a big, complex project, and I’m not a particularly good manager, but we’re making progress in spite of ourselves!

Cheers from the Microship lab, and thanks for your support…

You must be logged in to post a comment.