The Hostel in the Forest

Computing Across America, Chapter 15

by Steven K. Roberts

Brunswick, Georgia

December 1, 1983

A guest sticks a nail in the wall even if he stays but one night.

— Polish proverb

I did not expect to find magic in Brunswick, Georgia. I wouldn’t have been surprised by love, lavish southern hospitality, or even a pocket of decadent beach culture, but magic? In Brunswick? Nah.

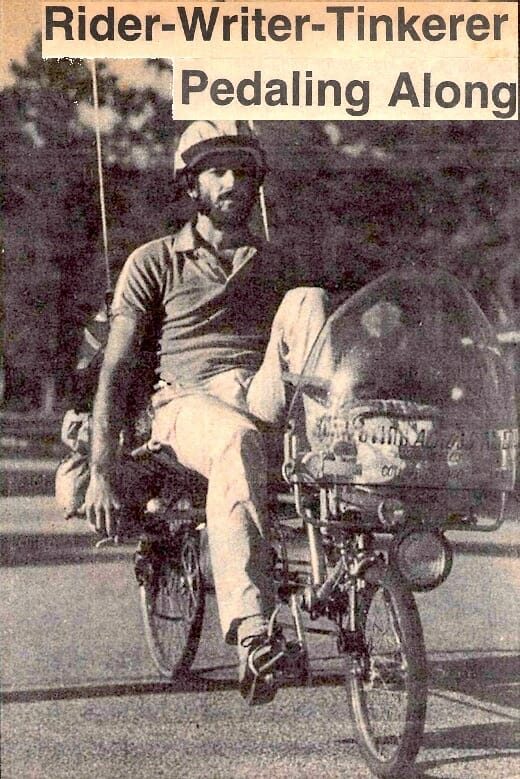

The 94-mile day from Savannah began with cries of “Good luck, Steve!” from passing cars. The Evening Press had done a story on me, and such exposure has effects both local and global. This one was picked up by Associated Press and later led to a magazine assignment. But a more immediate effect occurred out in the boonies, somewhere between Midway and Retreat. Sailing along in a tailwind with a hearty breakfast stokin’ in my gut, I didn’t notice the small-town speed trap.

Normally, of course, radar cops are of no concern. I have exceeded speed limits here and there, but most encounters with The Law have more to do with riding too slow where I shouldn’t than riding too fast where I should. So I breezed through the little shanty town without a thought for anything but the simple backwoods beauty of the day and the Sunshine State waiting a mere hundred miles down the road.

But then I heard a squeal of tires as the police car came tearing out of its hiding place — followed by the rising wail of a siren. Eh? He couldn’t be after me, surely, but there was nobody else around… I slowed from old automotive habit and felt the uneasiness in my stomach. He passed and pointed at me with a gesture to pull over.

I sat by the side of the road, nervous but bemused, recalling the southern cop stories I had heard — reports of people locked up for no reason, harassed, given burr haircuts, even tortured.

He walked toward me, studying me inscrutably through silvered sunglasses. He stopped with his hands on his hips and looked me over, one finger tapping unconsciously on the butt of his service revolver. “Good morning,” I said.

“Maaan…” he said in the kind of lazy, vaguely stoned voice you might expect of a jazz singer, “You be cruisin’, aintcha?”

I grinned at him. “Why yes… as a matter of fact, I am. I just rode from Ohio.”

“Yeah! Lemme have your autograph!”

“Well, as long as it’s not on the bottom of a ticket,” I quipped, and we both laughed. I signed a business card for him while he told me about seeing the article in the Savannah paper.

“I knowed you be comin’ down through heah if you be goin’ to Brunswick,” he said smugly. “I been keepin’ my eye out fo’ you all moanin’. Maaan… That is some kinda bike. Laid back! Hey — you wait right heah.”

He walked to his car and returned a moment later with a Kodak Disc camera — then snapped a couple of pictures, gave me an enthusiastic handshake, and sent me on my way.

Ah, hostels. They lie beyond the glitter of Hiltons, the multicolored neon of Holiday Inns, and the faded signs of rural motels. They appear in odd places, like Red Lodge, Turtle Lake, Ohiopyle, and Jack’s Reef. They take many forms, from musty suburban basements to exquisitely fashioned domes nestled deep in the Georgia woods.

As I wander America in search of tailwinds and modular phone jacks, I occasionally find these havens of the true traveler, tucked safely away from airports and interstates. No little strips of paper labeled “Sanitized For Your Protection” will be found here. Nor will machine-generated wake-up calls, plastic key fobs that you can drop in any mailbox, or tacky postcards with aerial views of a motel. Hostels have character, and each one is different.

The organization behind all this is Hosteling International USA (formerly AYH), which licenses these low-budget establishments and publishes a directory. Spending the night at a hostel can cost as little as two dollars a night, more commonly around four or five. But far from degenerating into cheap flophouses, they have become the preferred overnight stops of a unique breed of tourists. For this we can thank the “houseparents,” almost always seasoned world travelers themselves.

After a long ride through the wooded lowlands west of Brunswick, I turned onto the winding sand road that led to the famed Hostel in the Forest, appreciating my sealed-beam halogen headlight as I picked my way around puddles and rocks in the close blackness of the woods. Frogs peeped and croaked in the night, joining a few birds and the inevitable cluttering insects in a random chorus. The term “middle of nowhere” crossed my mind at least once.

And then I saw it, glowing softly through the trees. Two domes, interconnected by a rough-hewn, indirectly lit deck — and a treehouse, set off by itself in the woods. This is a hostel? I was accustomed to spare bedrooms and basements. I stared at the small cluster of buildings and feared that perhaps I had taken a wrong turn, that this was not a hostel at all but the residence of a now-wealthy carryover from the earth-conscious counterculture of the sixties. There was a grace, a balance about the place — not the functional “pack-em-in” character of public accommodations, but an organic feeling as if it had grown slowly from the woods around it.

A screen door slammed, and a voice called out above the frogs and crickets. “Hello?” it called in a German accent. “You are looking for the hostel, yes?”

“Yes, I am,” I said to the shadow in the dome’s doorway. “I take it this is it?”

“Oh yes, this is the hostel. On that bicycle you have come from Ohio? Sean said you had telephoned.”

The speaker turned out to be Thomas, a classical-music buff and teacher who travels the United States on the proceeds of an occasional profitable car deal. “In my garage now stands a Mercedes,” he explained in careful English. “It must change its owner next year.” A single import nets him six to seven thousand dollars — enough to support months of hosteling in this endless land.

He helped me wrestle the bike into the vacant central area of the sleeping dome. This was Sunday night and the weekend crowd of about fifteen had dwindled to three German Thomases, a fellow named George, and Sean, the Australian manager. I walked around on the Grand Tour and knew from the spirit exuded by the very walls that I would be staying a few days.

This place was a significant discovery for me. Perhaps it was the twin domes, one a community building and the other for sleeping; perhaps it was the treehouse, a lofty bedroom that sways slightly in the breeze and treats the early riser to an unparalleled forest sunrise. Or maybe it was the quiet, the clear sky, the misty pond, or the cocky rooster Leroy and his subordinate chickens. It was all this, I think, but it was mostly the people — people on journeys instead of trips.

What I found here was a unique community of travelers — a community that survives intact despite the constant turnover of individuals. The clientele is energetic, as varied as the far-flung lands of its origins. Here may be found a lone Japanese cyclist, a New York couple hitchhiking to New Orleans, and a startling pair of Swedish ladies learning English by plunging headlong into a three-month American adventure. Every week the faces change, but the hostel remains, its character deepened by those who have passed through.

The beauty lies not in luxury — you make your own bed, tolerate whatever temperature the night offers, and help with the morning chores. But a night here is a night in a community, a place that lays a gentle hand on your shoulder and bids you stay and relax. For four days I did just that, sleeping high in the trees and feeling the touch of morning sun. It was my first real taste of the traveling culture — a vaporous community that condenses here and there to share stories and camaraderie. Bonds form quickly and easily; deep friendships span the globe. It’s a town without a place, a people without a land: the sense of home is inside each individual, unrelated to real estate. Home is where you unpack for a while and share time with friends.

Home. That was something I had hoped to find by looking all over the United States, yet it was already there, tucked safely inside me all along. Home would surface whenever appropriate — when special places or magical people would take me into their arms and hold the lure of the endless road at bay.

I wrote this in their huge Guest Book and found it 4 years later:

To the Hostel in the Forest

(To Tom, Sean, and all travelers who give life to this place…)

Pedaling the planet, living on the “Winnebiko,” my 3-bedroom ranch in suburbia drifts hazily into memory. And with it (I thought) fades the notion of “home”—at least until journey’s end, whatever THAT is.

But no! Home materializes in special places, places like this where the fire is not a fire but a hearth, where people who yesterday had never met are today a family. It’s an intriguing notion, this idea of a rapid-turnover home—for it suggest the presence of magic. It can’t be expressed as the simple synthesis of gentle wilderness, supremely appropriate domes, starlight, and chickens. Even the rare spark of Tom Dennard, though obviously the critical catalyst, cannot account fully for this ambience. It IS all of this, but one thing more: the countless echoes of the people who have built upon this foundation with their very presence, forming a living monument to travel, sharing, humanity, peace, and yes, the pure wonder of living. Perhaps this explains it.

Then again, perhaps not. Maybe it’s just magic. But whatever it is, it feels good, and I tap away freely on the bicycle-borne solar-powered word processor with nary a thought for the madness of the outside world. This is the kind of home that can’t be bought. To all who have touched this place, I give my love; to all who ever will, I join with the others in a warm embrace of welcome.

Of this, are legends born.

by Steve Roberts 12/1/83

You must be logged in to post a comment.