Into the Real Mountains

Computing Across America, chapter 38

by Steven K. Roberts

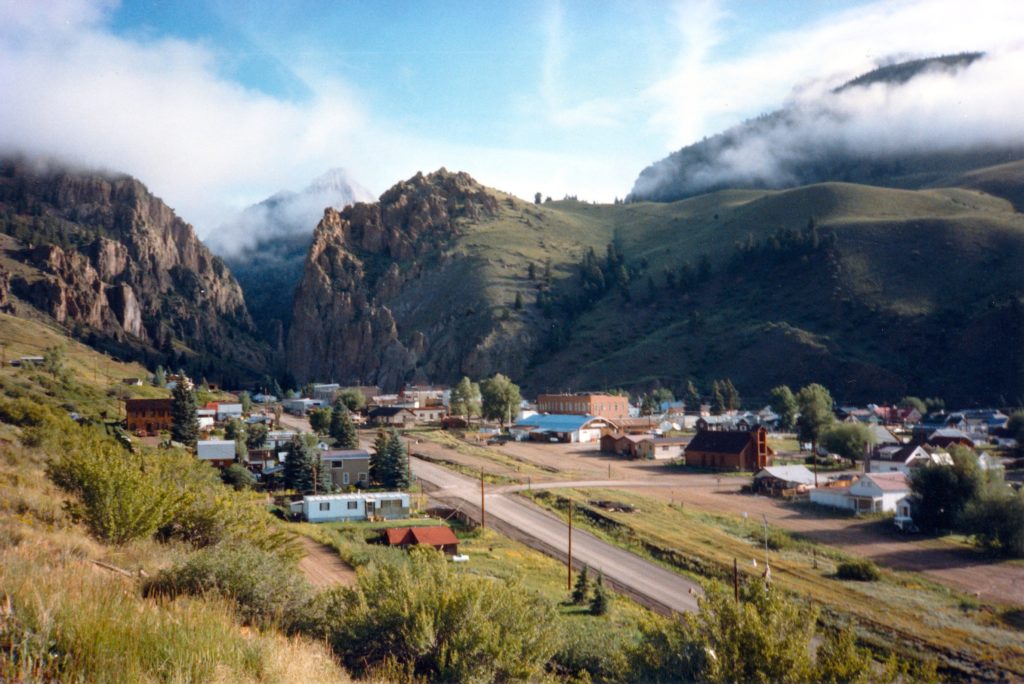

Creede, Colorado

August 18, 1984

I’ve always got a home in Colorado, no matter where I am or what changes I go through. If passing time leaves me troubled, wond’ring where to go, I know I’ve got a friend in Colorado.

Nancy Johnson, Mellow Lady LP

With crisp metallic freewheel-clicks, the loony excursion module rolled out of its final Santa Fe hangar to stand gleaming in the morning sun.

The solar-powered instrumentation package beeped softly as I scanned its internal data and reset the daily mileage to zero. A low-pressure cell had just passed, so I recalibrated the altimeter to show exactly 7,000 feet. It was 68° and 8:58 a.m.

I performed a comprehensive pre-flight check, for it had been almost three weeks since last I had flown the open roads. The photovoltaics were putting out 320 milliamps. The crackle of the CB radio was strong; Free Flight was poised in the cassette deck. The security system sensed even the softest tapping on the frame, lights and horn checked OK, and the water bottles were full.

Derailleur limits—check. Tire pressure—check. Brake pads—check. Cables, fasteners, connectors—check. Knees—check.

Ready.

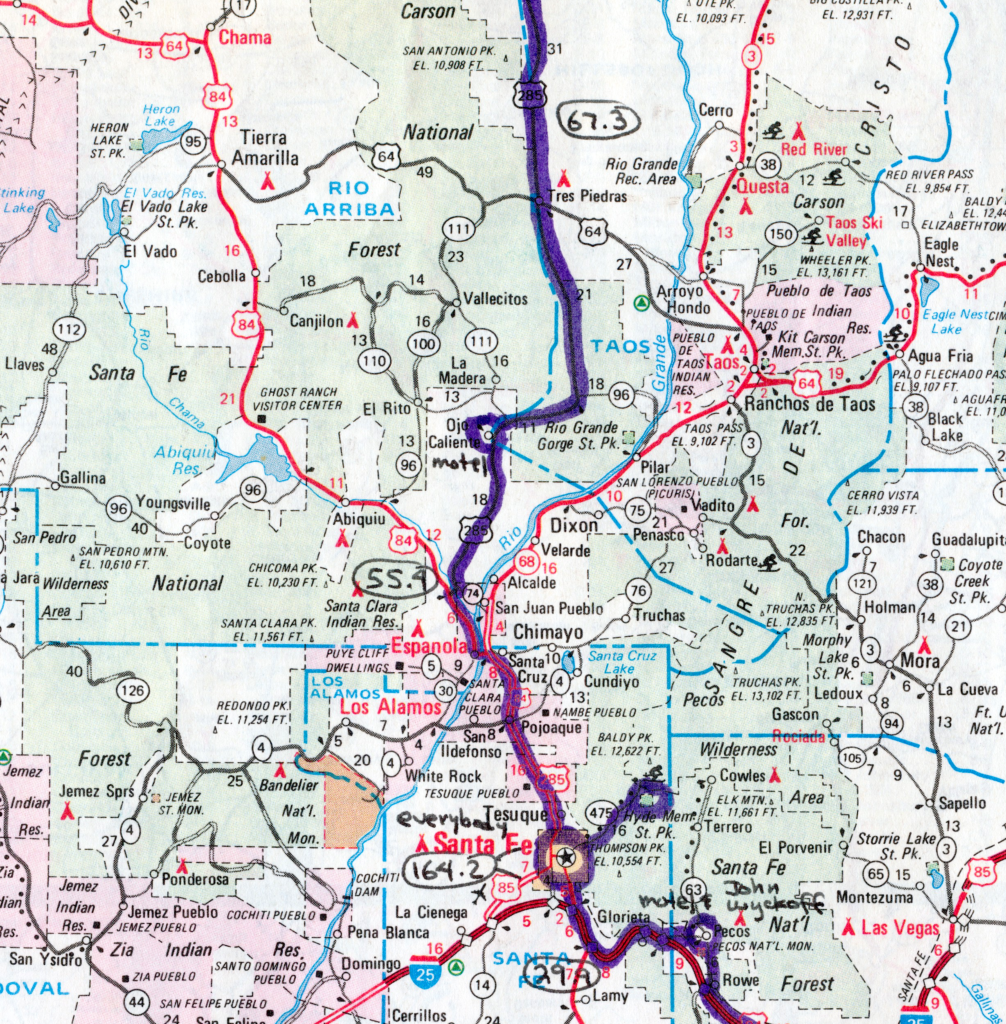

The Winnebiko had grown considerably, now pushing two hundred pounds and worth over $11,000. I rolled through town making my last round of visits, stopping at Chez Pancho for breakfast and at a gas station pay phone for the day’s mail. And with locusts singing electronically in the trees I left Santa Fe on a compass heading of 350°.

I climbed to 7,200 feet, then dropped in less than an hour to 5,800. I passed nervously through Española, a place, like Texas A&M, that has spawned its own breed of specialized jokes.

And after 55.4 unremittingly beautiful miles, I found myself in Ojo Caliente, back up at 6,300 feet.

Ojo. Oho.

I had already visited Ten Thousand Waves, a graceful Japanese hot tub and massage establishment in the Sangre de Christo mountains northeast of Santa Fe, but that could hardly have prepared me for the famed mineral baths of Ojo Caliente. These waters have been taken as a cure by New Mexico locals since 1860, and a sort of crude resort has been built around them — populated by an odd breed of tourist. This isn’t the gawking snapshot crowd but the old, quiet, native, and aware.

“Do you want arsenic or iron?”

“Uh, what’s the difference?”

The young shirtless attendant glistened in the hundred-plus degree heat of the bath building. He gestured at a row of streaked tubs separated by curtains. “Those are the arsenic baths, to cure your cuts and bruises.” He pointed toward a door in the back of the sweltering room. “Back there is the iron bath for muscles, arthritis, and the insides.”

“I’ll take the iron.”

He handed me a towel and told me to shower first.

Naked, I walked into the iron room, my breath catching in the hot blast of humid air. The walls were streaked with mineral deposits; a huge slimy green rock in the far corner was trickled with steaming rivulets. A corrugated fiberglass ceiling admitted a dim hint of daytime through dirty skylights, and six men were speaking Spanish, laughing, and lounging easily in the oppressive heat. Already I was thirsty and dripping with sweat.

I slowly immersed myself into the murky burning depths, trying to ignore the reddish scum of the surface and the fuzzy gravel beneath. The sunburn of my upper back began screaming agony, and the men chuckled as I fought my way inch by inch into the water.

“Soon you will not mind the heat,” one of them said in a heavy Spanish accent. “I have come here for many years.”

“Why?” I asked through my teeth.

He chuckled and patted the water as if it were the head of a good boy. “Because I go to many doctors. Arthritis. They take my money and do no good. Here? I find the relief. Iron water is the only thing know how to ease the pain.”

I looked above the slimy green rock (the magic rock, according to a fellow I met the next day) and saw a sign: PLEASE REPORT ANY SPITTING OR NOSE-BLOWING IN POOL.

When I could stand it no longer, I struggled weakly to my feet, feeling like poor Pieterzoon boiled to death in Shogun. I fought gravity up the steps and into the main room, where the attendant offered me a heavy wool blanket. “Will you be taking a sweat?” he asked. The idea seemed absurd — I was sweating profusely and dripping with the iron smell of the bath. But the main room was filled with tables, each bearing a miserable man sweating in a tight woolen cocoon. The guy was serious.

“No thanks,” I panted, my head spinning. All I wanted was cool air and maybe a beer or six.

The next morning I went for a walk in the wild rugged lands west of Ojo. Fresh in my memory was the magical masseuse, a woman who could have stepped out of a Castaneda book. Under full moon and meteor shower she had chatted matter-of-factly about spaceships, beings, spirits, “power places,” my healing hands, God, palmistry, Tarot cards, I Ching, and auras. She was forty, pretty, and part wild woman with long gray hair — and she fit the scene perfectly.

Tingling from massage and dressed in light shorts, I set out into the mountains alone, carrying an alto recorder. Higher and higher I went, past cliffs of sustained echoes, through trackless lands of sparse evergreen and the skeletons of trees long dead. Glittering surprises were scattered on the ground, and every peak was covered by a cosmic dump-truck load of rock ranging from motes to boulders. Perched atop one, I could see tomorrow’s road snaking up a distant ridge and disappearing into the haze — and beyond that, Taos.

Skitterings and echoing bird cries. Hot sun on relaxed muscles and sunburned shoulders. Sparkling crystals, yellow lichens, white clouds drifting across tan peaks with the blue sky setting both apart in exaggerated contrast. Nothing was disturbed; again I felt that sense of forever, of timelessness.

Afternoon. I was now at “Lake Ojo,” as they called it, a pebble-beached artifact left in the bulldozed wake of some human intervention. There were four of us, splashing in the sun, clambering about, talking, touching in the water, strangely intimate.

I went climbing again, probing the contrasts of this eccentric land, starting up a prehistoric waterway of rounded stones. Moments later I stumbled through a sloping expanse of sharp red rocks, then across a three-acre flat plain smooth enough for a tent city. I came to the edge and dropped through dense bushes to a sandy creekbed, then climbed up the other side, an almost vertical deep maroon rock face. I was living in a 3-D slide show gone berserk, the scene abruptly changing with every blink. From toehold to toehold I stepped flylike, risking my life in sensory delight, angling across a cliff face to the distant objective of yet another mountaintop.

Midway I heard a soft cry, and looked over my shoulder to see two of my friends making love across the chasm, she dancing astride him as he reclined in tan-muscled bliss on a smooth rock.

I waved and they laughed bright in the sunshine, their free rhythm unbroken. My presence was not an intrusion. The sight was no less natural than the soaring hawk above them or the ancient rock below. I watched with gentle <pangs> for a moment and then resumed the skyward climb.

The next day, 8,400 feet. He appeared as people often do, pulling off the road in a dirty white pickup and stepping out to wait for me. Fresh from a fine tamale lunch in Tres Piedras and energized by a day of music and stunning scenery, I pulled alongside with a pleasant hello. I welcomed the break. We were in the middle of nowhere on Route 285, about fifteen miles from the Colorado line, and the rounded bulk of San Antonio Peak loomed ahead and to the left.

Rank drunk’s breath washed over me. Oops. Danger lurked in his eyes; he was plastered but by no means weakened.

“What’s this?” he slurred.

I told him.

“Are you famous?”

“Yes,” I said, hoping to imply that messing with me could have serious repercussions.

“Big fucking deal.”

“Well, I’m not that famous.” I grinned at him, carefully watching his eyes.

“You’re sweating.” His breath was potent, the sour result of an all-day whiskey binge, no toothbrush, spicy food, and vomit. He stepped closer.

“It’s a hot day. Well, I better go …”

He slapped me on my bare chest with a strong hand and then held it there, sliding it back and forth in the slick of perspiration. “Uh, hey,” I began.

“You’re shweating! You have to rest.”

“Actually, I’m doing fine. Uh, look, I need to make it to Alamosa tonight. I better get going.”

He stepped back. “Yeah. You better go. I’ll keep an eye on you.” He was staring at me, staring at me, sliding fingers against his palm dripping with my sweat.

“Really, that’s not necessary. I’ve come a long way by myself.”

“Yeah? I can drive anywhere I fucking like.”

“Well sure, OK… Uh, take care… good meeting you.” I pushed off with a wave.

Less than a minute later he stopped in front of me again. I rode past with another wave. In my mirror I watched him spin out with a cloud of brown dust, screeching onto the pavement with the rising roar of a floored accelerator and sloppy dry-geared shifts. Behind me he slowed, following loudly for half a mile. I motioned for him to pass.

He pulled alongside and held up a can of Hormel chili, offering it to me with exaggerated gestures. I patted my stomach and shook my head no. He raced ahead and slid to a stop in the dirt. I rode past with an unsmiling nod. This went on, mile after mile; occasionally he would drive out of sight only to reappear on the shoulder over a little hill, waiting for me. I finally stopped to talk again.

“Why?” I asked in frustration.

“You don’ like me?” he slurred aggressively.

“That has nothing to do with it. I’m just trying to ride and think about my book.”

“Are you famous?”

“Working on it. I want to be alone.”

“That’s a ridiculous bike.”

“Well, it’s different, that’s for sure.”

“It’s fuckin’ ridiculous!!” He stepped toward me and laughed, not in control of himself at all. I kept an eye on his fists and my left foot pedal-poised for the sprint. I felt beside the seat for the dagger and quietly released the leather catch.

“Hey,” I said with a flash of inspiration. “Maybe we can have dinner later. Where do you live?”

“Antonito.”

“What’s your name? I’m Steve.” I handed him a business card. “Maybe if I don’t make it to Alamosa, I can give you a call.”

He grinned. “Yeah. You can stay with me…” He told me his name and number, which I made a show of writing down (along with his Colorado license number).

I spoke with finality, the deal concluded. “OK. I’ll get in touch. Thanks for the offer.” I shook his hand, very businesslike, then pushed off. He passed with a honk and was at last gone.

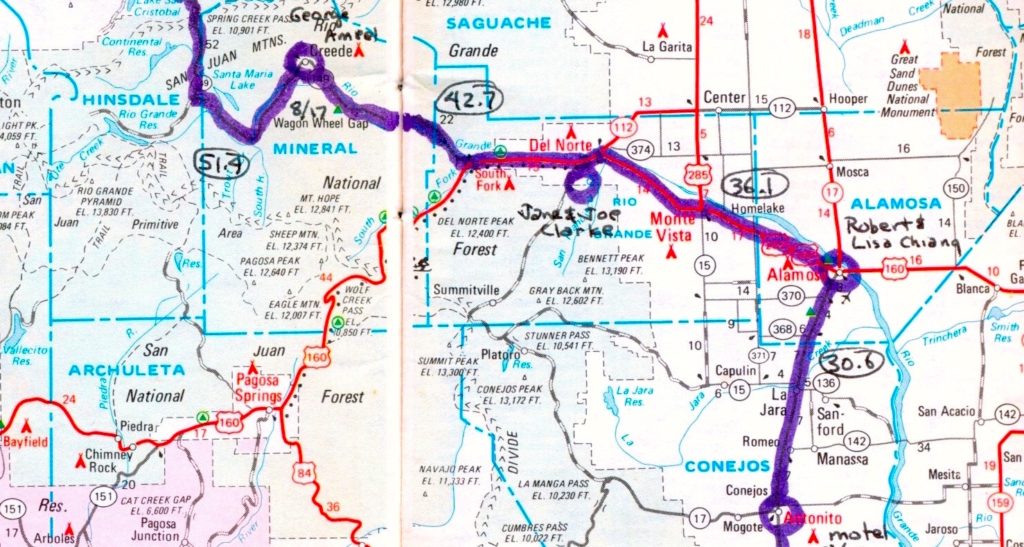

Colorado! Not since Florida had a state line so excited me. My thoughts soared with alpine images, even though the land was flat but for San Antonio Peak rising like a smooth green boil to the southwest. Colorado. Songs wafted through me; memories of photos and postcards overlaid themselves on the highway ahead. Colorado!

I stopped in Antonito, not to look up my drunk buddy but to stay in a motel. No doubt I missed a memorable adventure, but ya gotta draw the line somewhere.

Instead I met the Knickerbikers — the precise opposite of the macho cyclists. There were eighteen of them, rolling through the motel parking lot with smiles of easy camaraderie, a San Diego touring club on a two-week lazy loop out of Santa Fe. They were as casual as the others had been intense, so mellow that they made me look fanatic. We spent a relaxed hour in bike talk and exchange of addresses.

But our paths were merely crossing, for they were westbound to Chama the next morning on the Cumbres & Toltec narrow-gauge railway. I strolled to the station to watch them go — their colorful bicycles crammed in a freight car of this historic tourist train as it worked up steam for its daily run along mid-1800’s track. The old black engine was covered with entubated steaming modules; engineers in blue coveralls scurried about with oilcans. The Knickerbikers stood around, taking pictures of each other and triggering once again that wistful feeling that comes from watching friendships and families go on without me.

Hot steam poured onto the track and the cacophony of hissing and thumping rose to a peak. Cyclists piled into the “Capulin” car and the flywheels began chunking, smoke pouring black and gray from the stack, the whistle echoing off buildings behind me.

The Knickerbikers. The memory of the drunk. The lonesome train doppler-shifting its way westward into mountains. A new state ahead. No matter how often it happens, I can never quite harden myself to the stab of loneliness that comes from on-the-road good-byes.

I rode north through the San Luis Valley, across rich farm and ranch land that was once, long ago, a giant lake. Somewhere below was a layer of impermeable clay, making the whole area into a shallow aquifer — a source of political turmoil in the simmering drama of water rights.

Seems everybody’s concerned about water around here. In Alamosa, I stayed with Robert and Lisa Chiang, family of a dear friend from the library world. He’s an engineer working on a massive project to repay nearly a million acre-feet of water owed to Texas and New Mexico (that’s an acre of water 189 miles deep). Sounds loony as hell, actually, but they’re digging a hundred and fifty large-capacity wells in the giant sump that is this valley, collecting the water into convergence channels, then dumping it into the Rio Grande for the long trip south.

Repercussions range far and wide. Farmers are forced to curtail long-standing water usage habits. A family of “phreatophyte” plants depends on the status quo, and they will die when the water drops below their taproots. (“That’s OK,” say supporters. “Those aren’t native grasses anyway.”)

All across southern Colorado I met people involved in water issues — farmers talk about plant transpiration; attorneys talk about water-rights lawsuits; engineers talk about flowmeters and monitoring systems. This precious liquid is not taken for granted in the west, except by the lawn-sprinkling, unthinking rich.

But on a more personal level, it was the repeated glimpses of myself as a lone nomad that started having an impact. There had been little wistfulness in the south, in Texas. I had my moments, but always kept one eager eye on the road; I loved Austin and Santa Fe, but there was no sense of longing, no deep ache to remain. I lived with mad intensity, loving the road every bit as much as the layovers.

Colorado was different. The further I went, the slower I went. For three months, I averaged exactly ten miles a day, sniffing warm on the trail of hearth and community. It seemed that the higher and more remote the land, the closer were the people…

And even the dogs.

In Del Norte, I developed a hugging friendship with Sally during an evening of wine, chanterelles, and tectonic burgers. Conversation was of water, the beauty of sunset on wildflower-speckled fields, satellite TV, travel, and family. We began flirting early in the evening, and by bedtime things had grown serious.

But morning came, as it always does, and she watched sadly as I packed. “I’m doing it again,” I thought guiltily to myself, trying not to let her draw me into those liquid brown eyes. The road, the road…

The packing was complete. I took her in my arms. “Sally, I have to go now,” I whispered, as she pressed her big black muzzle against my cheek, held my hand, and leaned trembling into me. “I know I wasn’t completely honest with you at the start of our relationship, but I’m a trav’lin boy… I gotta be headin’ west.”

She whimpered and shook, fighting to contain the tide of emotion rising within her.

I drew back and gazed into her eyes, my hands lost in the soft fur under her collar. She parted thin black lips and bathed me with her tongue; I winced, but accepted the kiss. Her owner watched, smiling, understanding, saying nothing.

I was only sixty-six miles into Colorado, but I knew I would always have a home here. I snapped on my helmet and rode into the mountains.

You must be logged in to post a comment.