West Texas in July?

Computing Across America, chapter 35

by Steven K. Roberts

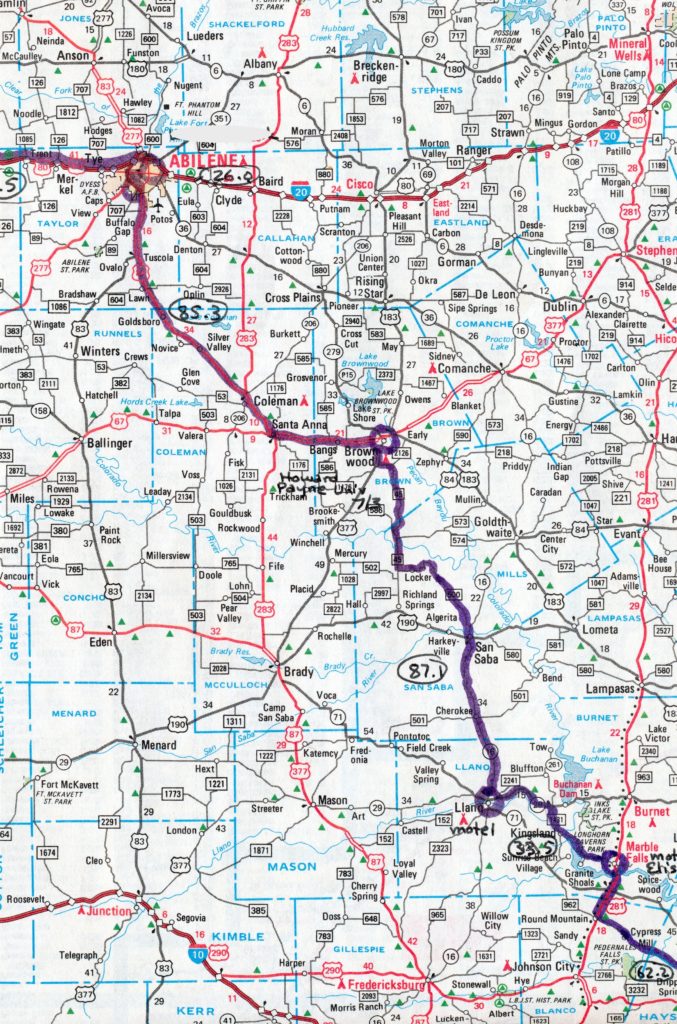

Lubbock, Texas

July 11, 1984

You’re crazy . . . It’s uphill all the damn way! Oh sure, you’ll go downhill sometimes, but even when you do, you’re gaining elevation.

—Advice about West Texas from a fellow in East Texas

She woke beside me and stretched, her hair the precise color of fire ants seething in the morning sun. “I had a dream about us,” she said sleepily.

I spoke in her general direction, careful to avoid catching her in a wave of morning breath (our relationship was yet young). “Hey, so did I!”

“I dreamed we were making love and people kept interrupting to ask about the bikes.” The fire ants invaded en masse and swarmed across my chest.

Well, I dreamed I was massaging you with Phil Wood bearing grease. That’s de rigueur for high-tech cyclists, you know.” I grinned at the ceiling. This was the day of our departure together for Texas hill country.

Stacey and her bike had flown from Boston to accompany me on the two-week ride to Santa Fe, a hot, gradually uphill trek of some nine hundred miles. She had read of my adventure while I was still in Florida, and this cyclo-tryst was the culmination of months of letters, fantasies, and planning. Her bike was a recumbent as well, a commercial high-handlebar model known as the Tour Easy, and we had just spent four days fine-tuning our machines and cruising Austin. “Ah, another one!” cried a guy at Mad Dog & Beans one day, then noticed the steering. “Oh, but this one’s normal.” I teased her about that as the days in Austin passed.

She was impatient to hit the road and I was dragging my feet. Hell, I liked Austin. “You can have women fly in from all over the world, just to not travel with you,” she suggested one evening with a trace of annoyance. OK. Let’s do it.

We rode out of town on familiar paths, my bike loaded for the first time in weeks. We looked like a new-age motorcycle gang, and everybody did the shuffle-turn as we passed — a characteristic sound that means they have shuffled to a stop and turned to watch. (When I hear it now, I wave without bothering to look.) Ahh, moving on. I had forgotten how good it felt. Through the rolling roads of Zilker Park we went, then into the hills.

But there was trouble ahead: we were of vastly different speeds. Twenty-eight miles into the day, Stacey far astern, I perched along the rocky roadside to nurse my second water bottle. Sharp cedar droppings prickled my ass through black nylon shorts; sweat trickled my chest. We were nearing the Pedernales River, and the land was much harsher than the rolling woods and cool rivers of Austin. Tiny towns. Scrubby cedar on dry hills. Few cars. Oppressive mid-90’s heat, better described as “furnace” than “sunny day.”

We had already fallen into a dangerous pattern. I would lose her in my rearview mirror and find a place to wait. By the time she had caught up, I was rested and ready to move on. This was annoying to both of us, and the warm smiles of our four-night stand had already turned to grimaces.

The bike appeared, its rider flushed and “not feeling, as they say, a hundred percent.” Uh-oh. It occurred to me that I had been doing this for quite a while — gradually becoming acclimated to the heat and stress, developing a sense of pacing that let me pedal for hours without fatigue. I had never thought of myself as athletic, but maybe I was. Stacey, on the other hand, had flown down here from cool Boston springtime and was accustomed to the breezy rides that connect New England towns.

So now it was noon on our first day, and we were already changing our opinions about this joint trans-Texas trek. Her skin had become the color of her hair; her hair had become a confused tangle. I watched in concern as she lay exhausted in thin rocky shade, halfheartedly nibbling at a sandwich, not noticing the prickly cedar. I wasn’t being very supportive. The thought of nine hundred miles… could be grim.

But a treat was in store only a few miles down the road. HAMILTON’S POOL said the sign, and I flashed back to a night in an Austin bar when someone had told me of this place. “Go down that little road just about till ya think I’s lyin’ to ya… then go three more miles. Don’t leave hill country without checkin’ it out, man.”

So we turned onto a dusty gravel drive, passed by carloads of shirtless rowdies and the occasional family. There was no evidence of water, but we paid our bill and found our way through a full parking lot and past the restrooms. Still no pool.

But then we came to a precipice and unconsciously grabbed each other’s arms, looking down onto lush trees and a sparkle of water. Distorted boom-box music and laughter echoed out of a huge hole in the ground, with splashes and the clink of bottles conjuring beach images. There were even whiffs of suntan oil. We followed steps into the earth and found ourselves in a cool, breezy, verdant oasis — a natural pool at least a hundred feet below mean ground level.

We stood on a pebble beach strewn with coolers of beer and about two hundred sunbathing bodies. Women rafted bikini-clad in the clear water, dogs sniffed about on missions of urgent canine intrigue. The whole place was half-covered by an inverted rock semi-dome decorated with mossy stalactites — dripping cavelike and bathing us in the cold wet night air of Earth itself. It set up a breezy turbulence as it poured into the hot shock of burning Texas sunshine.

High above us, hundreds of birds darted around inside the giant bowl, visiting each other’s mud apartments like a whole population of Jehovah’s Witnesses frantically seeking a single unsaved fugitive. Above this flying frenzy, backlit along the rim in broiling sun, a few guys peered down in buzzed machismo and dared each other to jump. Someone shouted up from the water: “Come on, Roy! Jump, man!” The rafts backed off in a semicircle, and Roy took himself a deep breath and a big swallow of beer. Hell, ain’t no turnin’ back now.

And as the girls squealed, he jumped — striking the water with a resounding clap-boom that startled the proselytizing ornithopters and set off a human chorus of whoops and cheers. The stunt scored so many points that his long flight was immediately followed by three or four vain attempts at one-upmanship.

Stacey and I relaxed together in this geo-cultural non sequitur, realizing that our shared adventure was ending. By nightfall at a Marble Falls motel it had been verbalized — she would head back to Austin, re-box her bike, and fly to cooler lands for some less stressful touring. I would press on through the hills and the dust, the mesas and the mountains.

Fire ants stood at parade rest on the pillow and blue eyes gazed sadly across the zone between us. The ménage à trois hadn’t worked. That Other Woman can be a jealous bitch sometimes.

It was noon, east of Llano, hard-core hill country behind me. The land was scrub, rocky, hot, open, vast; the temperature was 94°. To my left were the endless parallel threads of the Southern Pacific railway and the mostly dry Llano River. I pulled into a little roadside picnic area, whizzed vitamin-yellow through chain-link fence, and sat munching GORP… good ol’ raisins and peanuts.

I felt energetic, mobile, and free.

A maroon pickup truck pulled in beside me, and an old man with a hearing aid got out. I heard desperate, tired meows.

“You got a cat in your engine,” I told him, remembering a secretary of long ago. (“Oh, is it dead?” she had cried in response to the same statement, shrinking from the frightened mews of the kitten who would soon become Cybercat, trapped under the hood of her old black Chevy.)

“What’s that?” he asked, turning up the hearing aid. “Ya got a cat in your engine,” I said again, pointing.

“Ain’t got no cat. Must be on your rig somewhere.”

I walked over and tapped the hot hood. “Sounds like he’s in here.”

The man ignored me and opened the passenger door, poured thermos coffee into a styrofoam cup, and began eating a sandwich. The desperate cries continued.

“There’s a cat in your engine compartment,” I said again.

“What’s that?”

“Could you open your hood, please?”

“What the hell for?” He was getting annoyed at me.

“There’s a cat in there.”

“What cat?”

“The one in your engine!”

“I ain’t got no God-damned cat, I tell ya!” But he opened the hood, and against the firewall crouched a sweating, terrified, very pregnant brown and black tabby. She panted heavily and shrank from my hand as I reached for her.

“Well I’ll be damned,” the man said. “Wonder it ain’t dead.”

I carried the cat to the picnic table and tried to make her accept some water. She squirmed in panic, scratching me. I finally squirted the bottle down her throat and attempted to calm her down.

“Where’d you come from?” I asked the man.

“Midland. It’s a wonder it ain’t dead. Hot in there. Had one once got into the fan — godawfullest racket.”

“Midland! That’s a coupla hundred miles!”

“More than that. It’ll die, of course. Just glad it weren’t in my pickup.”

The piteous creature, crying and shedding profusely, broke from my grasp and ran across the highway in a wobbling, gravid gait. She crossed a barbed-wire fence and began trotting west, back to Midland. I watched in silence until she was out of sight.

“It won’t last long out there,” the man said. “No water. Coyotes. Say, that’s quite a rig you got there…”

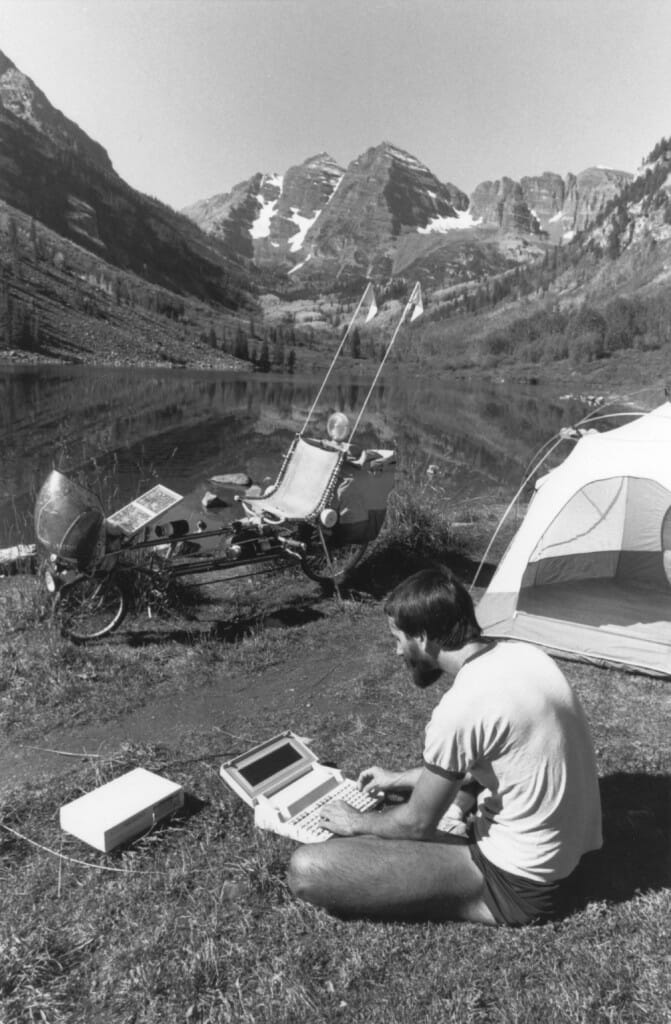

In the Dairy Queen of Llano, Texas, I flirted with Hewlett-Packard via pay phone while my “belt buster” sizzled, appeared in the serving window, and slowly cooled. The little Radio Shack Model 100 computer had been seeming less and less adequate of late — using it for any kind of significant writing project was like trying to run a company from a spindly Queen Anne candlestand. No file drawers, no workspace, no corners into which I could shove random clutter. Doing a feature-length article required getting rid of the mail, and I dreaded the very thought of using it to do this book.

Popular Computing had recently featured the new Hewlett-Packard Model 110 Portable, an exquisite machine with flip-up display, lots of memory, and battery-powered file storage. I wanted one in a big way. I lusted after one. I whimpered at the thought of honest-to-God word processing, of carrying my archives on micro-disk. I had dreams about the lovely thing; I rode along in the heat, fantasizing about a bicycle-borne computer more capable than my Ohio-based system. But they cost $3,000, plus accessories.

<pang>

A little publicity can go a long way, however, and it was an enthusiastic Hewlett-Packard that I found via that Dairy Queen pay phone. “How about a swap?” I asked. “Lots of media exposure in exchange for a Portable?” The music in the background was country and western; the lunchtime chatter was about the upcoming Fourth of July celebration. A tall, stubbled Texan in cowboy hat, leather boots, and denim shirt open to hairy navel stepped out of his gun-rack-equipped pickup and sauntered in. An old man picked his teeth while another cheeked up a plug of Red Man. I was standing in the self-proclaimed white-tailed deer hunting capital of the world.

And on the other end of the telephone line was Silicon Valley personified, fairly crackling with high-tech energy. We fell in love. By the time I had forced down the cold belt buster and called them back, we had a deal: my new computer would meet me in Santa Fe.

Hot damn!

Riding West Texas was a trip back in time, a crossing and recrossing of cultural boundaries, a new insight into the term horizon. I pedaled north from Llano, past an airport with four private planes and a landing strip like a rancher’s driveway, into lands vast, rolling and endless. From the tops of hills I looked out over ranchland, jutting rock formations, cactus, close- cropped grass, cedar, and yellow flowers. This is big country, and brutally hot, but the humidity was low and my skin was cool to the touch. I had a tailwind, and with morning energy I climbed hills in a tall gear just for the stretch.

In Cherokee, a tiny town with a pure Americana post office and a store featuring an Independence-day special on snuff, I stood at an ancient pay phone and edited a USA Today article.

In San Saba, I sat in Circle D’s and waited for food. I had enough time to write another whole story. In a world where the pace is slow, even life on a bicycle seems manic and hurried.

In the middle of nowhere on Route 500, I found a bike shop. No town, no neighborhood, just a bike shop. Desperate for something cool, I pulled in, met the owner, and swilled a quart of co-op water. The thermometer had passed a hundred degrees by now and the old man watched with concern as I returned shirtless to the road.

Indeed, the heat was beginning to take its toll — by the mid-afternoon home stretch to Brownwood I was fading fast. The tailwind turned into a curse, as the mass of hot air moving along with me prevented normal cooling. The water in my black-velcro bottles seemed to scald. Everything, everywhere, was hot. Hot. HOT. The asphalt was a molten slick that sucked at my tires; I left grooves on the road and picked up rocks that stayed with me for a while <tink-tink-tink> before becoming thrown or trapped in the sludge of my fork crowns.

Suddenly: Psshhhhhhh!

Shit.

The heat and stress had blown off the rear valve stem. Dizzy and weak, I rolled the bike into the shadeless ditch and replaced the tube — a miserable experience that involved unpacking and fighting caked sticky asphalt while burning my bare legs on the parched ground. There seemed to be no relief in this hostile land.

I was out of water with ten miles to go. My heart fluttered. My tongue was a numb-tingling dying thing, dry and alien in my mouth.

Then Brownwood at last. I met two Baptist girls in a Datsun pickup and joined them at Pizza Hut for a quart of Coke and two quarts of water. By nightfall I was installed in a guest room at Howard Payne University, playing Uno and Rage with a clean-cut Bible-belt college crowd.

But that could hardly have prepared me for Abilene.

I arrived on the Fourth of July (after passing with appropriate chuckles through the “bang-up good little town” of Bangs), and immediately dropped by a celebration in a local churchyard. Lemonade. Dunking booth. Hot dog stands. Backward softball throw. Sing-alongs. Tug of war. Three-legged race. Egg toss. Square dancing, brass band, and rousing speeches about reaffirming our creed and being thankful for liberty.

This is the capital of Americana, wholesome and friendly, patriotic and religious. I did an interview with KTAB television, perhaps giving ’em a somewhat different view of just what it was they were celebrating on this Independence Day.

I made my way over to Abilene Christian University, the largest of the city’s three religious colleges. No shorts above the knee are allowed on campus. Couples may be no closer than six inches. No mixed swimming. No dancing or drinking. Mandatory daily chapel; mandatory nightly sign-in at 11:30 (and you must wear shoes while doing so). No dorm visitation. No miniskirts. No earrings on men. No visits to Abilene discos. No, no, no, NO. Until recently, the only dating allowed was to the auditorium to hear the Dean’s wife play the piano.

I floated around an apartment pool and asked a student why on earth he, like 4,669 other people from thirty-five countries, had come here.

“Academic excellence,” he said.

“Aren’t there other places to get that?”

“Not like here. This has the best pre-med program in the state—we have an eighty percent acceptance rate.” He beamed proudly.

“But how can you stand the social restrictions?”

“You get used to it.”

“Was this your first choice of college?”

“It was the most liberal of the alternatives my parents offered me.”

Aha.

I hung around Abilene long enough to sense the restrained intensity of a religious community. Natural urges held in check lead to strange behavioral changes — from a passion for learning to a passion for God to a passion for the animals. I took one female student for a lap ride, and even apart from the fear of disciplinary action she was nervous. It wasn’t that she thought I was after her (I was very careful); it was fear of her own reaction. When I pulled her close to improve balance and give my legs room to move, she whimpered with something bordering on terror and thereafter had trouble meeting my gaze. I saw the guilt, as obvious in her pretty brown eyes as in those of a housebroken dog that couldn’t wait any longer.

All that love and fellowship without natural release: we’re creating a subculture of human time bombs.

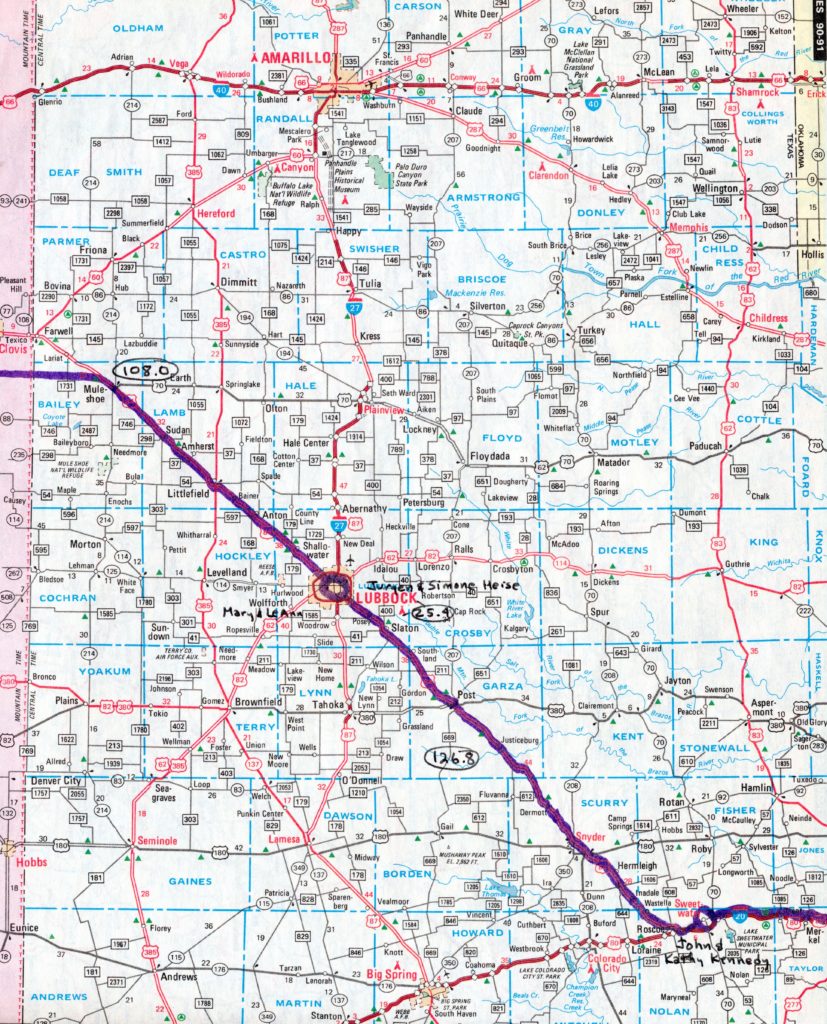

I continued west from God’s country with Lubbock the objective. The land was now just big — big, dry, and dusty. The feeling of drought was underscored by a woman lazily casting a fishing pole in the baked gravel lot of a used tire business, dreaming of water.

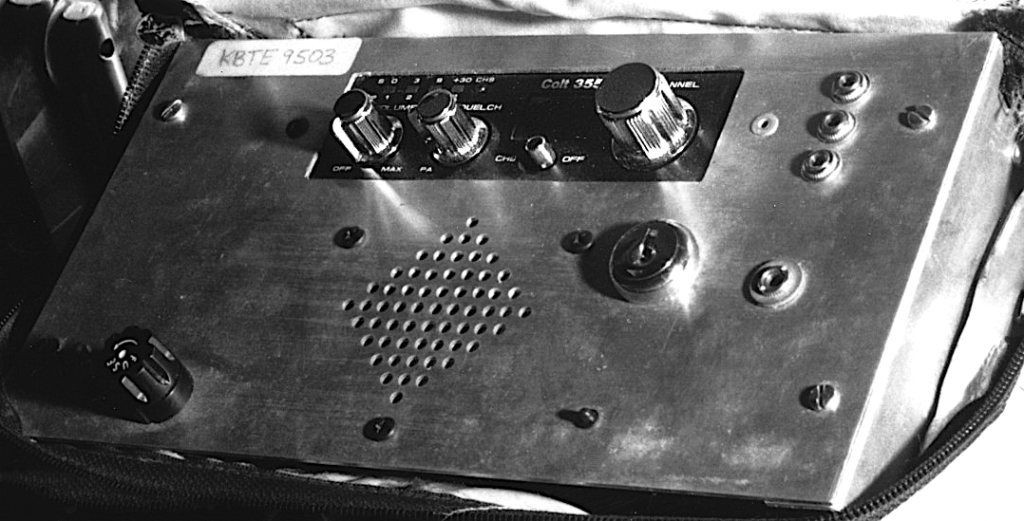

I rode I-20 near Roscoe, about to turn northwest onto the arrow-straight US84 for my last two hundred miles of Texas. The CB was on — useful along truck routes.

“Hey, lay an eyeball on this crazy guy over here on the service road.”

“I see him. What the hell kinda rig is that?”

“I don’t know — some kinda laid-back bicycle. How’d ya like to cross the country on that?”

“Too much work for me. I’ll stick with this here air-conditioned 18-wheeler.”

“Yeah, fo’ on that. I don’t know where he comin’ from, but the dude must have some kinda leg muscles.”

“Got some kinda head muscles too, riding a bicycle in this heat.”

I said nothing; I just rode along grinning at the conversation. It was typical. Suddenly there was a new voice. “Hey, I don’t believe this! That’s the guy ridin’ around the country with a computer! I just seen him on TV back up the road. Biker, you got your ears on?”

I fumbled for the microphone. “You got the bicycle here.”

“Hey there, rider! Where you headed today?”

“Lubbock.”

“Lubbock! Hell, that’s two hours by truck, ol’ buddy, and it’s uphill all the way. You must be goin’ to the Olympics.”

Someone else broke in. “Lubbock? On that? I tell ya, it ain’t gonna get any cooler out here today.”

“So I hear.”

“Shit, dude, you’re crazy. That’s workin’ your feet off to give your butt a ride, ain’t it? How you power that radio, anyway?”

“Break.” Another new voice. I pedaled along, microphone in hand, as the truckers roared by.

“Go, breaker.”

“Rider, if you want a Coke, you’ll find me up here in a white pickup, 10-4?”

“Hey, I appreciate that! Where you at?”

“Up here by Roscoe. If you’re goin’ to Lubbock, you’ll come right past me.” Sure enough, I saw a white Ford pickup pull off the road about a mile ahead. We kept up a banter until I was on his back door, as they say in the idiom… then the whole family hopped out and handed me a cold drink. Ahhh.

Good old Texan friendliness. It occurred to me that nobody had thrown anything at me since south Florida, and Indiana still held the national record for unwarranted abuse.

And after a new one-day record of 126.8 miles, I was in Lubbock.

Lubbock is the home of Texas Tech, and it’s a flat city of simple layout, a place sunny 265 days a year. There’s an active bike club, but I quickly sensed that they weren’t my type. I met them for a group ride and they were aloof, macho, fast, and competitive. I ambled back as they raced away.

The town was an odd mix: people opened up easily but said little. (“Uh, doesn’t that little front wheel slow you down?”) The TV station called me Steve Carlton throughout the broadcast, lingering on the little Push odometer as the voice-over discussed the computer. In this context, my hosts shone like gems, liberal and colorful.

Jürgen and Simone had been among the people who had offered me a place to stay on my first pass through town. They had ridden a tandem bicycle from Anchorage, Alaska, to the tip of the Baja, and proved to be interesting hosts.

We ate one night at The Great Wall, going in search of their famed Mongolian Barbeque. “It’s nice,” Simone had said, “It’s like being a million miles away from here.”

“Interesting definition of ‘nice’.”

“Hm. Doesn’t say much for Lubbock, does it?”

The restaurant was anything but West Texas. We filled bowls with raw veggies, beef, chicken, turkey, and pork, then ladled on sugar water, garlic water, ginger water, soy, and hot sauce. This we handed through a window, where a guy from Taiwan deftly cooked it all on a shallow four-foot wok, adding sesame oil, wine, water, and other seasonings. No limit. Exquisite tastes. Plum wine and candlelit conversation.

This graceful dinner was in sharp contrast with our later visit to a redneck dive full of leathered bikers and ragged characters of all descriptions. I felt conspicuously clean-cut in my bicycle-shop T-shirt and nylon shorts. The beer was cheap, the music loud; I was seriously worried when Jurgen took too long to return from the men’s room.

But the culmination of the Lubbock stay was the start of another ménage à trois with the Other Woman — this time with a good-looking man instead. Let’s see how she likes that… if she’s like human lovers I have known, that will make all the difference in the world.

We joked about this, Jürgen and I, as we set out. We talked about ménage à trois, ménage à quatre, and other variations, then I added, “Well, there’s always good old ménage à un.

We began grunting in unison: “Un, un, un!”

You must be logged in to post a comment.