Plunging into New Mexico

Computing Across America, chapter 36

by Steven K. Roberts

Villanueva, New Mexico

July 15, 1984

Wilderness. The word itself is music.

Edward Abbey, Desert Solitaire

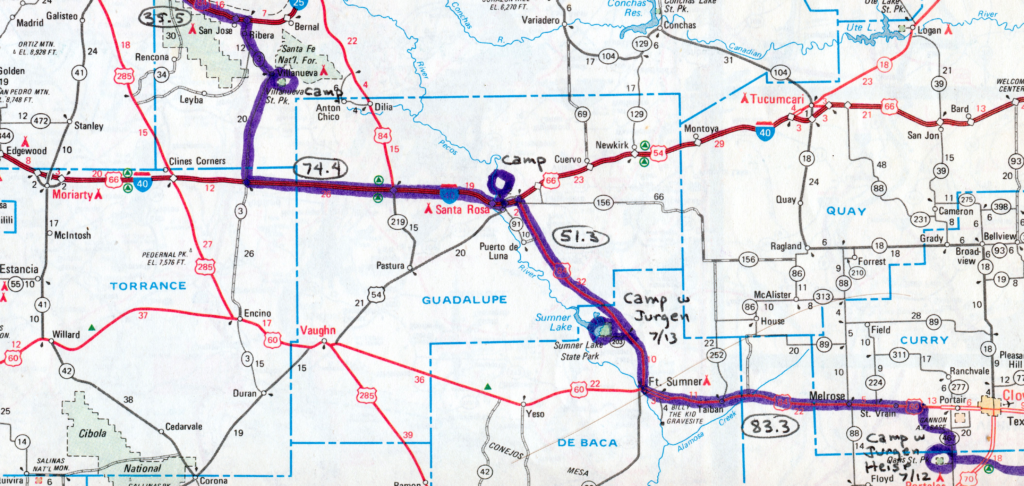

We did a little dance, the three of us, a sort of farewell boogie to Texas. I had just passed the 6,000-mile mark, and Jürgen and I were getting along beautifully — different enough to be interesting and similar enough to be compatible.

Yes, now there were three of us: Jürgen, the Other Woman, and I. She liked this liberal, bearded German with the ready wit and hearty laugh, and she was much more cooperative than she had been with Stacey. Little dust devils skittered across arid cotton fields plucked by Chinese migrant workers. A robust K-Bob’s lunch refueled us in Littlefield; an onion fallen from a produce truck appeared as the Road’s contribution to dinner.

But the real pas de trois began near Muleshoe. The third party was now a black, lightning-ridden thunderstorm to the west, a crazed and dangerous interloper on a day of blue sky and puffy clouds. It stayed with us on an obvious collision course, growing closer and larger as we burned up the tailwind miles.

In Muleshoe we stopped for snacks at a grocery, and the edge of the storm brushed the town — peeking in windows, looking for us. We hid under the awning and trickled sticky plum juice into our beards, watching the attacker roil in dark confusion. It seemed unsure, irked at our disappearance. We weren’t playing fair, lurking like this. Alright, you bastard…

We waited for an opening, then hopped on our bikes and sprinted north as Muleshoe caught the full brunt of the storm’s wrath. “There you are, you wimps!” it cried, as furious on our asses it came, chasing us northwest, gaining slowly. It bore down like a tireless battleship overtaking a pair of kayaks, firing its Big Guns with bright flashes and boneshaking explosions.

“Over here!” Jürgen cried, his voice urgent but small in the thunder. A farm road veered to the west — toward blue sunny sky and the distant puffy brown wake of a tractor. With the battleship only a few hundred feet astern, we turned, hustling furiously, hell-bent on staying dry. In less than a minute the intersection behind us was lost in a gray mass of rain, as flashing cannon highlighted the STOP sign and picked off an occasional four-wheeler.

And then it was sunny. Heh. Within the hour, hot and sweating, we crossed the border into New Mexico.

You know, there’s something about state lines. You might think of them as meaningless political boundaries, but they often seem to demarcate physical regions as well. Immediately the terrain changed, the crops changed, everything changed. Gentle rolling farms nurtured corn and alfalfa with huge rainbow-generating “siderolls” — rolling irrigation systems as wide as whole fields. Beside the road grew clusters of fluffy green tufts and other alien things. All this intensified the sense of really getting far away from Ohio.

As sunset began we pitched our tents on a remote hilltop, distant radio towers flashing red above the horizon, the air clear and filled with the lonely sounds of croaking nighthawks and wind-rattled leaves. We camped in high desert between the orange sky-glows of two cities — Portales to the south and the larger Clovis to the north. And as mosquitos feasted on our ankles, we conjured a deeply satisfying dinner of found onion, canned chicken, pumpernickel, herring, cereal, and tabasco sauce in various combinations — all washed down with screwdrivers of vodka and Tang. Hey: after 108 miles, anything tastes good.

It had been a perfect day.

The next one sucked eggs.

It began with a shortcut. Clovis Air Force Base was closed to passing cyclists, and on local advice we started down a dirt road. “Oh, just ahead there a ways you can turn on up to the highway — it’ll save ya a few miles.”

With F-111s zooming overhead we hit the dirt, Jürgen losing me in the dust of his lightly loaded twelve-speed. My machine weighed 115 pounds more than his, and I bogged down, loose soil sucking at my wheels and drawing me into the earth. Pedaling was impossible. With a curse I slowed to a stop and sat fuming, watching as my friend puffed easily across a vast valley without me and then settled down, a distant relaxed speck, to wait.

So that’s what it feels like. Sorry, Stacey.

A monster recumbent with under-seat steering is not an easy thing to push. Bent over with one hand on the seatback and the other on the handlebar, I began wrestling the machine through soft dirt. The miles ahead seemed absurd. Why I didn’t turn back, I don’t know — I should have returned to the pavement and waited for Jürgen to come looking for me. But I was stubborn and/or stupid, so I continued throwing good sweat after bad until the thought of turning back was at least as overwhelming as the thought of going on.

When I finally caught up with Jürgen out in the middle of some farm, he pondered the problem and suggested a set of reins. My back was aching from the bent-over pushing position, so with his help I rigged a rope loosely from one handgrip to the other and resumed the battle from behind, steering with my little fingers. He disappeared again, and for the next two hours I sweated profusely, practicing my cursing skills and filling my shoes with gritty New Mexico dirt.

Nice shortcut… we could have hit that highway more quickly via Texas. I was too exhausted to appreciate the first glimpse of mountains, a ridge lying dark on the southwest horizon like a line of brewing thunderstorms. The beauty was slowly growing; drama starting to touch the land after the emptiness of the last few days. But I was in no mood to notice — and for the first time I regretted the weight of my machine.

Onward. We flew energetically west, smooth pavement a sensual treat after the morning’s ordeal. I stopped to take a roadside leak in a dry ravine and looked down, startled, as a grating sinister hiss crackled the dry New Mexico air. I was soaking a rattlesnake.

With a yelp I leapt straight back as the serpent, pissed both off and on, coiled for the strike. My graceful yellow arc of a moment before had become a wild spray, and even as I touched down from the brief flight I was running backwards — immediately encountering the guardrail and pitching over into a dribbling heap.

No… this isn’t Ohio. Look before you leak!

We raced downhill into a huge misty valley, our destination only minutes away. This was the end of our ride together, and Simone was to meet us for a night of camping at Ft. Sumner Lake State Park.

Gravel roads, steep hills. Campers, fires, fishermen, grills. We zigzagged the lakeside campground seeking his lady, and as I started up a short intense grade I flubbed a shift.

Now, I had flubbed my share of shifts before, but never under full power. I tried to slam the chain down to the little granny gear, that 21-inch stump-puller that lets me climb anything, but I was cranking with eyeball- straining effort at the same time. The bike stopped abruptly with the middle chainring folded in half.

No… oh, no… It was dark, and at least a hundred miles to the nearest bike shop. I was now in possession of a heavy high-tech bike with a severely injured TA triple crankset. I stared morosely at the thing as Simone drove up, assessed the situation, and handed me an emergency beer. Not optimistic, I disassembled the gears, carefully spreading out the twenty spacers and fasteners on a picnic table. The folded aluminum chainring seemed hopeless, but with earnest bendings, stompings, and rock-bangings I managed to sort of flatten it.

The bike’s weight might have been a curse earlier in the day, but I was suddenly glad I had all those fancy crank-pullers and metric wrenches.

Alone again, forty miles into a downwind day of progressively more impressive views. The land had changed from half-vast to vast, and I was so busy marveling that I almost passed the disabled car with Ohio plates.

“Hey, Ohio!” I called, braking abruptly beside the steaming hulk. “Need help?”

The driver, a vacationing policeman from Mantua, looked at me without enthusiasm. Of what use was a guy on a bicycle? He shrugged and told me that his radiator had boiled dry.

“Wanna use my CB?” I asked, offering him the microphone.

“Well, I’ll be…” He grabbed the mike and went into CB lingo. “Breaker 19. How ’bout that northbound Big Mac. You got a copy on this broke down Ohio four-wheeler?”

“Yeah, four-wheeler, what’s the problem?”

“I need some water bad.”

“I ain’t got no water on here. Why don’t you holler down to the truck stop in Santa Rosa — they got their ears on.”

This he did, my solar-powered radio covering the seven-mile line-of sight distance with ease.

I continued north toward Interstate 40, and reached to kill the crackling noise of the CB. Trucker chatter was irrelevant out here in open country, but my hand froze on the switch. What?

A heated racial battle was going on between a black guy in a white Buick and a white redneck in a black truck. All the classic cliches flew back and forth, all the hateful slurs, all the references to watermelons (“ghetto steak”), Jesse Jackson, welfare, and Cadillacs. The hostility escalated rapidly, with more than one invitation to stop and “talk about it.”

“If yore boy Jackson gets elected, he’ll paint the Statue of Liberty black ‘cept for the palms, and call it Aunt Jemima. He’ll put all the nigras to work and put the whites on welfare, an’ he’ll move the White House to Birmingham. ‘Cept it’ll be the Nigra House.”

“Go spit on yo’ white ho’ mama’s nose, muhfuggah.”

“You wanna say that to my face, boy?”

“I’d be happy to say it to your pig-face, assho’.”

Et cetera. It was funny for a few seconds, then made me feel sick — these guys were dead serious. They didn’t even know each other, but they wanted to hurt each other anyway.

As the battle faded into the static where it belonged, the latest news began to spread: the county mountie done a flip-flop at the two-seventy-six and is now rollin’ eastbound. Yes, even as you read this, such radio-borne conversation penetrates your walls and permeates your body, right in there with random propaganda and a golden oldie or two.

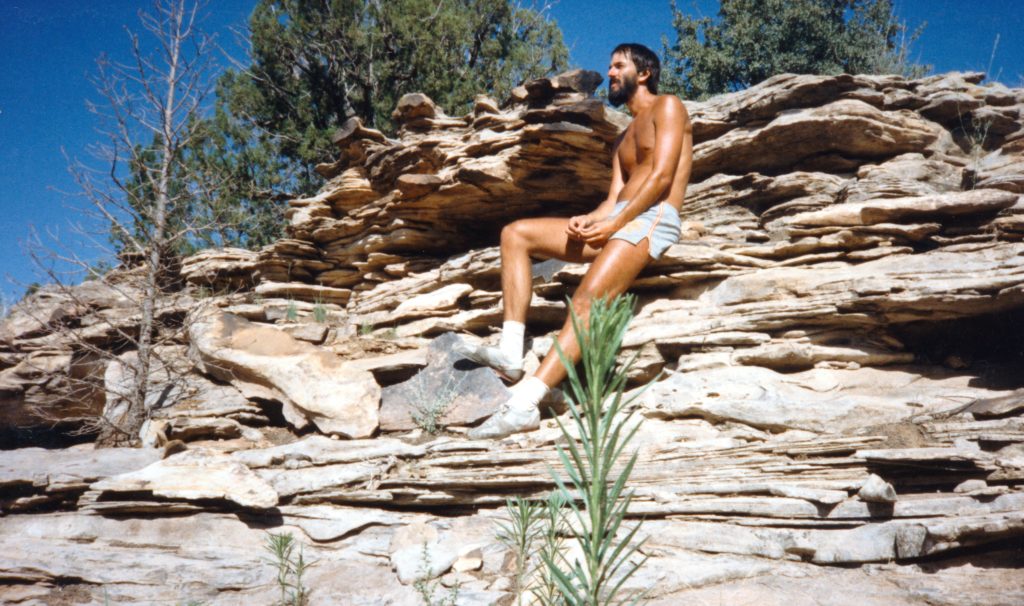

Santa Rosa, New Mexico. It could have been the set of a wild west movie. I pitched camp near a dry creek bed, surrounded by cactus, sun-bleached driftwood, and white rock layered hard and flaky like a giant stale baklava. In mid-July sun my skin had become brown and sweat-glistened — on impulse I made certain of my solitude and then disrobed to creep nude through the wilderness, sneaking up on rabbits, touching cacti in wonder, and pondering the unity of things.

Yeah, something in my vision changed abruptly in the wilds of eastern New Mexico. I sensed, walking naked in that endless land, an order—a balance. The fancy bike and computer were incidental; they had gotten me there, but they were not the journey. That’s an easy thing to forget in the glow of public attention, the constant questions about steering linkages and solar panels. I walked softly and felt the rock hot beneath my feet, the sun burning into me, the eyes of a rabbit looking back in recognition… and I realized I was part of it all — a native, a human animal.

I stretched out on a rock, kissed lightly by the breeze. Gravity was part of it too, this force I was spending more and more of my time fighting. I relaxed and let it pull on me; feeling it in my tongue, my gut, my muscles. Silence. A bird. Somewhere the delicate gurgling of water beneath rock. My breath. All part of the same system, the same planet. My cousin the rabbit watched, nibbling automatically, sensing no threat.

We high-tech humans have a critical job before us — a rethinking of our place in the order of things. We have come to see ourselves as different from all the rest; we think of ourselves as the players, producers, stagehands, audience, and even reviewers in some kind of huge passive theater. That “all the world’s a stage” metaphor can be taken too literally: we’re all in this together — you, me, the rabbit, the rattler, the cactus, the black guy in the Buick, the storm in Muleshoe, the Corynebacterium tenuis in your armpit, and the two Hispanics who tried to sell me dope in that Santa Rosa campground. (Yeah, and the Russkies too.) One planet, one system, one whole. That’s easy to forget when the universe appears to be a thing of human creation, a multichannel abstraction delivered via cable to a glowing box in the living room.

Try walking naked in the wilderness sometime. Do it alone and without thoughts of sex. You get a lot of interesting answers without having to ask any questions.

That night at the campground I met a New York couple. Hurry, hurry, go, go, go — sorry, can’t stay to watch the sunrise, jump out of the tent and break camp, awchrist I can’t find the fucking map, jog to the shower, hustle, hustle, leave the goddamn beer bottles, somebody’ll pick ’em up, sorry Steve, gotta run, nice meeting you, off to Phoenix.

Phew.

What was that all about?

“This is our vacation,” explained the engineering manager over his shoulder as his wife smoked and fidgeted in the car. “We don’t have time to relax.”

Morning, breakfast at a Santa Rosa restaurant. I ate while watching the show around the bike, feeling again like a curiosity. Four men leaned against cars in the parking lot, pointing at various parts of my strange machine with their feet and talking in Spanish.

Then an old cacafuego showed up as I was preparing to leave — the kind of guy who asks questions carefully calculated to make bystanders think that he not only knows everything about it, but designed it as well.

“I know it’s a crossover drive!” he said, irritated that I would presume him ignorant of such an obvious fact. “Ya gotta watch out for this thing here.”

“That’s my shifter.”

“I know. I used to build these things. You’re using — ah yes, those.”

“Eighteen speed.”

“That’s right. You need it on this kinda rig. Which make of plate ya got here?”

“That’s a solar panel.”

“Yeah. For the motor.”

Ah, got him! “No motor,” I said with a note of triumph and a glance around at the audience. “It’s all pedal power.”

He laughed derisively, an old pro at this game. “No motor! Well you better put one on if you’re headin’ west! I still got some lyin’ around the shop …”

But it didn’t take long for that feeling of oneness with the people and the land to come flooding back, striking me with a poignant sense of a culture fading.

It was a tiny road, an escape from the trucking roar and Smokey-the-Bearanoia of Interstate 40. Hot asphalt again grooving under me, sticky pebbles tinking against dusty stays. Sweaty, tired, counting the miles, dreaming of beer. This was Route 3 to Villanueva, northbound, and I was moving closer to my new computer with every stroke of the pedals.

To the west a pair of thunderstorms dumped rain; to the north, the sky was dark and pierced by lightning. They closed in as I growled up fierce grades in my ultra-granny gear.

Then it hit. I stopped on a high ridge and did the crude plastic routine, tucking garbage bags under bungee cords and covering the small packs with baggies and shower caps. I slipped sweaty into my rainsuit and flew downhill, the drops stinging, the street steaming, the incredulous drivers passing with Spanish exclamations unheard.

I rounded a bend and flew <Jesu!> down the most dramatic hill I had seen yet — a valley to the right bounded in craggy reddish rock, wet green and hazily pastoral in the middle. The road clung winding to the high-cut mountain face, plunging into this fold in the southern Sangre de Christo, forcing me to apply brakes wide-eyed to avert disaster on the slippery surface. I sailed at 34 mph into a ramshackle adobe town from deep in the past, and stopped to ponder my next move.

Everybody in Villanueva waved and smiled. An old man clasped my shoulder and said earnestly, “God be with you, my friend.” I saw no Anglos. Through town, people staring, I found my way to the state park — a place where youth and families cruise and picnic. Lightning struck once, so close that my xenon strobe fired.

“Haaay, that’s a bad bike, mon. How fast you go on that?” Three young men approached, boom box in hand severely distorting something in the disco genre. I answered their questions and accepted a beer.

“You wanna smoke a joint, mon?”

¿Por que no? Introductions all around, fumbling cultural-pride handshakes (standard “brother,” regular, and hooked fingers), hissing sips of marijuana smoke. Spanish banter among themselves, eyes darting at a passing cop with the joint and brew held low. It’s odd to be a minority, at least for most of us, and I was acutely aware of my difference — the sense of vulnerability amplified by smoke and the swirl of voices straight from a Cheech & Chong album.

“Hay, mon, don’t forget our names for the book.” I turned on the tape recorder and one guy got paranoid. “Uh, I’m Pat, and that’s Johnny, and over there is Lee.” He looked at the microphone nervously. Their real names were Hispanic.

Buzzed and tired in the growing dusk, I switched into recumbent BMX mode and scrambled up a rocky dirt road to a covered picnic table — pitching camp on a concrete pad under a corrugated roof. The land around me was a study in shades of black, from the sky with intermittent stars and fast-moving gray clouds to the impenetrable tree-lined murk of the Pecos valley floor. I kept getting a sense of west.

It was a long night. The wind was furious on that slope of rock and scrub: the unstaked tent lifted, fluttered, sought to fly off the ridge. On ant-infested concrete wet with midnight rain, I woke and savored the wildness. There were not only bumps in this night, but also crashes, whirrs, knocks, crunches, booms, flashes, skitterings, and whooshes. Once a voice spoke close and furtive; later a single harsh bark, only inches from the tent, shocked my heart.

And in the welcome daylight I met Delfinio Torrez.

I stopped in town to buy food and fetch EMAIL via the primitive pay phone, and there he was, unassuming, kind, seeming a part of the earth like the adobe houses rising from the dirt of their own foundations. He spoke quietly of his town, its history, their church — taking me across the street to visit Our Lady of Guadalupe.

“We must be reverent,” he said gently, and I left my pint of milk outside. He dipped his fingers in holy water and crossed himself, then we slowly walked around the chapel, the spiritual center of town.

The room, filled with simple pews, was lined with tapestries or colcha, one 265 feet long and winding around the walls and up to the balcony like a mountain road. Framed over its whole length in dried cactus, it told a pictorial history of Villanueva, the ancient Indians, the Spaniards, the park, the church — this was the legacy of a people who see themselves as a people. One life-size tapestry of Our Lady of Guadalupe had taken over five hundred hours to create.

We climbed into his pickup truck and toured the land, meeting an eighty-four-year-old man building a new house. The dirt excavated from the foundation is mixed with straw and sun-dried into eight- to ten-inch adobe blocks, which are then piled precisely into walls. Still standing are homes hundreds of years old, and occasional hybrids of adobe and trailer lend a touch of modern tackiness to a place conscious of its heritage.

“Was this originally an Indian town?” I asked Delfinio, turning on my tape recorder.

“Well, there was Pueblo Indians here before the Spaniards. And then the Spaniards came and integrated with the Indians, and that’s how we got our culture. A little mixture of French, and so forth. Now, being that we’re isolated, we didn’t get into the melting pot as fast as back east.”

“It certainly has a whole different identity.”

“Yeah, and we try to conserve all these things, but with every generation we lose a little bit.”

“How much do you think that has to do with television, and the general American image? Young people must see all that and get restless, thinking, Wow, man, what am I doing here?” I was thinking of the trio I had met the evening before — more reminiscent of inner city than a deep-rooted agrarian culture.

Delfinio rubbed a hand through his black hair and looked at me sadly, his face crinkled by five decades of New Mexico sun. “Well… yes… it started real bad in World War II. The kids got drafted and went away… and they seen the outside.” He spoke this last word with a touch of mystery. “OK? And they seen there was easier ways to make a living, and they start putting emphasis on education, and the first thing you know — there wasn’t this roots. It started breaking up. They were simple people, and yet very content — and then they decided that money would make them happier. You lost this contentment; you went to this idea like ‘the Joneses’ and ‘dog eat dog’ and transportation and television… and the moral part of the thing got away from them, you know? In the long run, what do you got? The more you have, the more you want.”

I looked around at the town, at the peaceful faces, the smiles. By American economic standards this was poverty — but by spiritual standards it was wealth. Yet it was a fragile, anachronistic wealth, with TV antennas, Honda three-wheelers, and dissatisfied youth marking the death throes of an era.

But that need not be tragic. The magic lives on; I see it in eyes everywhere. People have been seduced away from the simple life as long as there have been new toys and greed. This is a component of change, and some folks never will appreciate the simple pleasures, the illuminations of the mind — the true components of success.

And so towns slowly die of attrition; cultures grow obsolete and fade. But towns are also born, and new cultures grow from the rich compost of the past. Even as Pat, Johnny, and Lee are turning their backs defiantly on the heritage of Villanueva, others are opening their eyes in recognition of human potential. From them arise new communities energized by urban dropouts, new age thinkers, and refugees of suburbia.

It’s just taking too damn long.

You must be logged in to post a comment.