Word Counting Utility for Writers – Byte

I’ve had a rule since I started being a geek freelance writer in the early 1970s: everything is copy! In other words, build no contraption or tool (or even client project) without mining it for at least one magazine article. This of course helped feed my addiction to gizmology, and from the perspective of 2023, looking back at my life, it also forced me to document far more than I ever would have considered. Indeed, the stuff that I didn’t publish is effectively forgotten… even in cases where I still have old listings or schematics.

This is an easy one – a little Z80 assembly language tool to help with the writing business itself. It’s pointless now, of course, since the info comes free in any text editor, but back then it was pretty cool. The story was a minor piece in this issue of Byte, which carries cover artwork by Robert Tinney.

by Steven K. Roberts

Byte

June, 1982

A microcomputer fully configured for use as a word processor is a valuable and addicting asset to a writer, as anyone who has spent more than a few minutes grappling with a typewriter can well imagine. I doubt that I would be trying to make a living in this volatile word business if my trusty word-processing computer system, BEHEMOTH, weren’t here to deal with the brutal realities of somehow getting text from my head to paper.

But writing, it turns out, also involves a variety of data-shuffling tasks that are not directly involved with text editing and formatting. And then there’s that fairly trivial but age-old problem of counting the number of words in a manuscript. Yes, you can multiply some average word count per page by the number of pages in the manuscript, but that’s inelegant and fails to accommodate stylistic variations that can have significant effects on the length of the average word.

The word count of a manuscript, by the way, is more than an idle bit of trivia born of a love affair with information. Primarily, it is a key specification in article assignments, since the amount of space available to an editor of a publication is predetermined. (Opening the reference book Writer’s Market 1981 at random, I note that Bird Watcher’s Digest accepts nonfiction articles in the 600 to 3000 word range and fillers of 50 to 225 words.) Second, word count is a part of most book contracts, a fact that is giving me little rest these days (180,000 words, it turns out, is a lot). And finally, observing the amount written each day in some sort of dispassionate and objective fashion can provide useful feedback concerning a writer’s output.

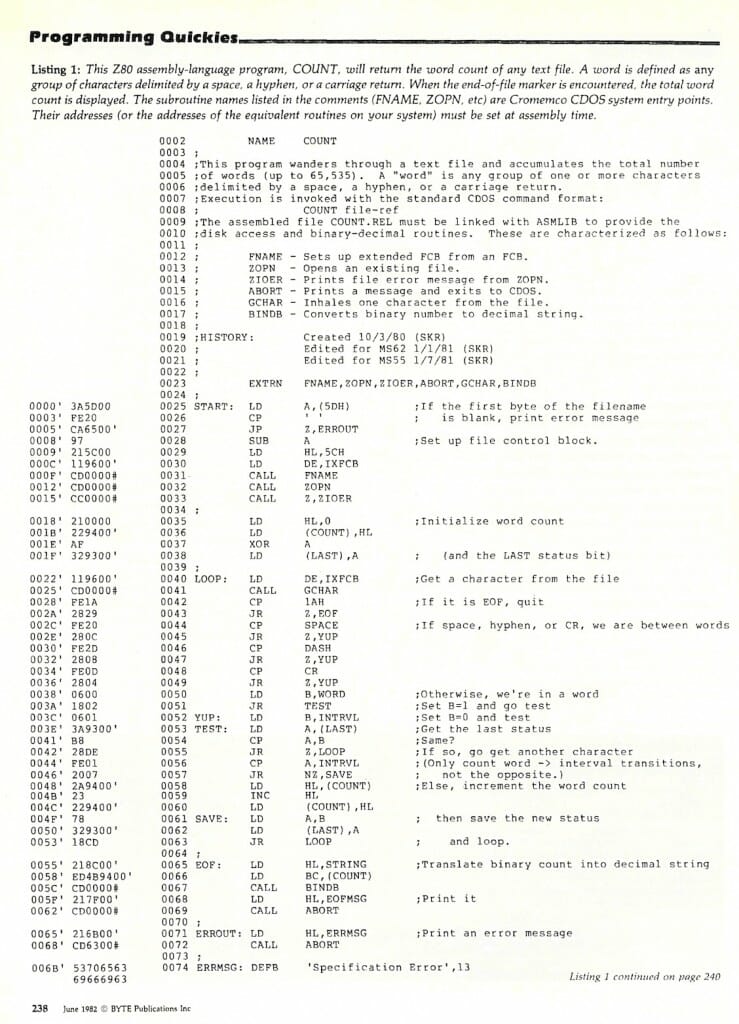

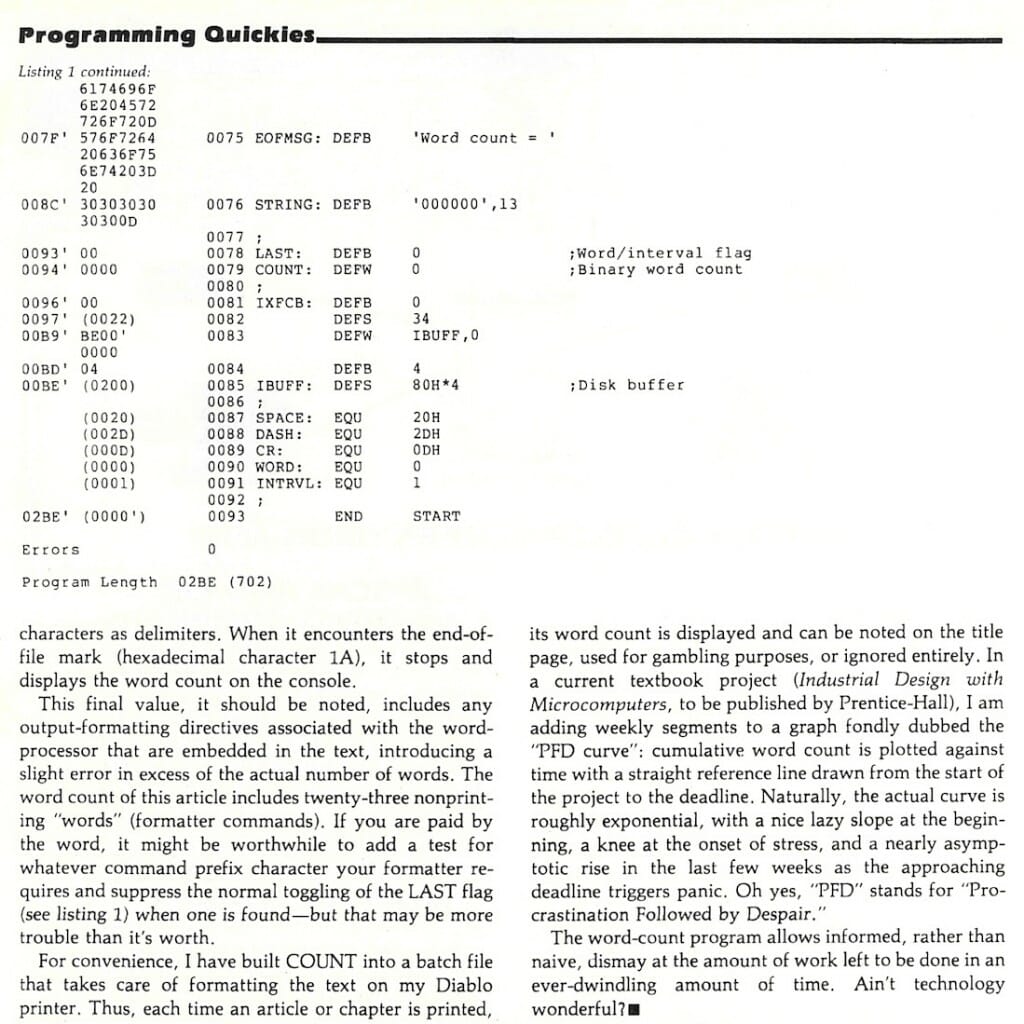

If all that text is in the form of disk files, it becomes quite easy to let the computer do the counting, and the Z80 assembly-language program COUNT (see listing 1) accompanying this 781-word [Before editing….Ed.] article does just that. Designed to be run under the Cromemco CDOS operating system, it can easily be adapted to CP/M-based systems, while the concept behind it can be applied to other personal computers.

Use of this utility program is straightforward. To count the words in this article, the program is invoked with the command line: COUNT C:WORDCNT.M62.

The text file is called WORDCNT.M62 (the manuscript serial number is 62) and happens to be on floppy disk drive C at the moment. The COUNT program just reads the entire article and accumulates the total number of words, using the space, hyphen, and carriage-return characters as delimiters. When it encounters the end-of-file mark (hexadecimal character 1A), it stops and displays the word count on the console.

This final value, it should be noted, includes any output-formatting directives associated with the word processor that are embedded in the text, introducing a slight error in excess of the actual number of words. The word count of this article includes twenty-three nonprinting “words” (formatter commands). If you are paid by the word, it might be worthwhile to add a test for whatever command prefix character your formatter requires and suppress the normal toggling of the LAST flag (see listing 1) when one is found—but that may be more trouble than it’s worth.

For convenience, I have built COUNT into a batch file that takes care of formatting the text on my Diablo printer. Thus, each time an article or chapter is printed, its word count is displayed and can be noted on the title page, used for gambling purposes, or ignored entirely. In a current textbook project (Industrial Design with Microcomputers, to be published by Prentice-Hall), I am adding weekly segments to a graph fondly dubbed the PFD curve: cumulative word count is plotted against time with a straight reference line drawn from the start of the project to the deadline. Naturally, the actual curve is roughly exponential, with a nice lazy slope at the beginning, a knee at the onset of stress, and a nearly asymptotic rise in the last few weeks as the approaching deadline triggers panic. Oh yes, “PFD” stands for “Procrastination Followed by Despair.”

The word-count program allows informed, rather than naive, dismay at the amount of work left to be done in an ever-dwindling amount of time. Ain’t technology wonderful?