Bicycle-Mobile R&D Lab

One of the most challenging parts of packing the Winnebiko II (and later BEHEMOTH) for open-ended travel was dealing with the need for tools… not just the usual little bag of bike tools like spoke wrench and crank-puller, but all the stuff needed to continue development of the electronic systems which, by definition, are never “finished.” This short article in the 73 Magazine series is a quick tour through my solutions at the time, with a couple of photos added 29 years later.

I have many a fond memory of building and debugging in campgrounds and hostels… good times!

Practical Points for Inhibited Experimenters

by Steven K. Roberts

73 Magazine

June, 1988

It can happen anywhere, and usually does. I wake in camp, breathe the vapors of morning inside a billowing nylon cocoon, rustle a warm hand from the depths of my sleeping bag to touch KA8ZYW, and lie there thinking intently. “Hmmmm, if I let the new TNC handle speech control in parallel with the BCP, then I can sign on via packet from the HP and carry on a synthesized conversation with people around the bike… monitoring their audio on 49 MHz. Gee…”

Maggie’s hair cascades across my neck. “You were talking in your sleep again,” she murmurs. “Is a speech-control bus some thing the government uses to arrest boring politicians?”

Those are the first clues. Over flawless campground coffee, I stretch, sketch, and mumble, scan my listings and schematics, regale the morning-sweet YL with complex tales of logic and technomagic. The maps are forgotten and there’s no rush to pack… for it’s a tinkering day!

Well, so now what? There’s no room on a bicycle for diagnostic tools, documentation library, R & D inventory, prototyping board, and drafting equipment — or is there?

One of the things I’ve learned from this whole traveling circuits of mine is that no complex system is ever finished. And while reliability has been generally excellent, I find a lot of reasons to crawl under the hood and do some engineering. As such. I’ve had to put together a passable mobile R & D lab… and in this, the fifth column of the series, I’d like to take the reader on a quick tour.

The First Issue: Documentation

If I had to work on the Winnebiko from memory, nothing would ever get done for fear of screwing it up beyond recognition. A project in progress becomes etched so deeply in the brain that the builder is sure he always remember exactly how it works. A few grim all-nighters of staring glumly at undocumented creations, however, dispelled that fallacious notion from my head. I now carry three forms of documentation on the bike:

- A clamp-style binder, stuffed with about ¼” of schematics, listings, operation notes, wiring specs, idea sketches, and so on. This is the irreplaceable document that completely defines the custom parts of the electronics package, and I periodically photocopy the whole mess and mail it back to my office as a backup.

- An “aquarium of microfiche” containing highly reduced copies of key IC data books, software and hardware manuals, reference guides, and so on. A 20X Keyan reader gives easy access to what would otherwise amount to 15-20 pounds of books. I have also added Buckmaster’s microfiched amateur radio call directory, a number of maps, and other convenient reference material.

- A subdirectory of disk files on the HP laptop, defining operating procedures, the functions of all controls, and other variable information. This includes the Bicycle Control Processor’s source code listings and — equally important — a sprawling file of comments and narrative explanations associated with each of the 15 major revision levels. This has proved invaluable time and again, as I wade hesitantly into an obscure backwater of this real-time program and wonder what madness possessed me back when I wrote it.

Adding new documentation is something that should happen at the time of any change to the system, of course, so my “R & D pack” also contains a small case with basic drawing tools and templates.

Tiny Test Bench

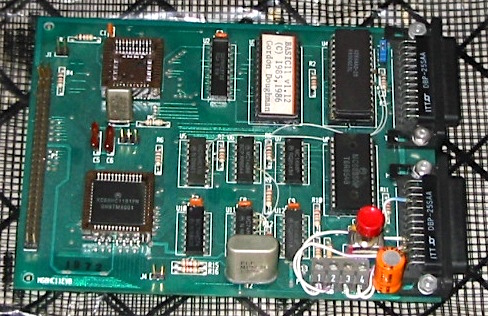

With space at a premium, I had to forego a few basic essentials. I carry no oscilloscope, function generator, spectrum analyzer, hammer, or milling machine. But I do have a logic probe, digital multimeter, SWR bridge, prototyping board, software development system, bench supply, built-in current monitor, “Quick-Connect” wiring tool, butane soldering iron, and extensive toolkit.

It’s amazing how much can be done with a few basic lightweight tools when the constraints of a nomadic lifestyle demand it. My software contains a library of test loops that exercise all I/O logic in a way that makes it amenable to debugging with a logic probe and development system. Internal jacks offer convenient supply voltages for prototyping, and a ledge inside the console even carries a permanent parts tray and soldering-iron stand. The point of all this, of course, is to make development work as painless as possible… even if it happens in a campground.

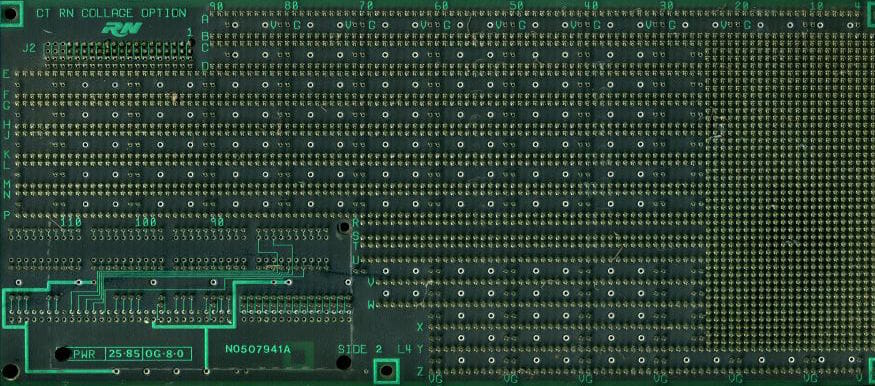

Easy prototyping depends upon a convenient packaging method, and I use the Robinson-Nugent Quick-Connect boards exclusively. They’re faster than wire-wrap, lower profile, and more rugged (a major issue on a bicycle). The boards arc hinged in my installation, so modifications can be made without having to unplug any connectors or dangle live hardware from a cable harness.

One more thing. Despite convenient on board equipment, there are still occasional projects that require more in the way of support facilities than I can carry. I keep a list of such “long-range TO-DO’s” on disk, and scan it whenever I find myself visiting some one who owns a well-equipped lab. “Ahhhh… I see you have a spectrum analyzer. You know, I have some birdies that have been giving me trouble… got a near-field probe for that thing?”

The Junk Box

As we all know, no lab is complete — or even possible — without a well-equipped junk box of tinkering stock. It’s just not possible to experiment effectively if the only access to components is a shopping list (hamfests and surplus stores notwithstanding).

I carry about six pounds of parts, as well as a bag of fundamental essentials such as Ty- raps, wire, heat-shrink, and the like. There is a sheet of antistatic foam with a hundred or so 74HC glue parts, along with a collection of particularly interesting devices I just gotta have. (You know how it is: “Well, someday I’ll find a neat use for a high-speed array processor on my bike… sure, I’ll take it.”) There are a few dozen individual Zip-Loc bags, dedicated to such things as R’s, C’s, D’s, Q’s, connectors, switches, ferrites, packaging parts, mechanical hardware, spade lugs, and so on—with, amazingly, enough depth and variety to support a typical day of tearing into the system with new ideas in mind.

Keep On Tinkerin’

The bottom line, of course, is that no-one need be prevented from experimenting by the constraints of a nomadic, cramped, or socially hampered lifestyle. I have an old friend who lost the spark of tekwizardry when he got married and settled down. The books in the living room were unrelated to geek passions, the dog was a designer model far beyond their budget, and all that electronics junk just HAD TO GO! But a single desk can hold enough to keep the creative spark alive — enough to keep the nose wrinkling with the acrid smell of solder… the eyes gleaming in the light of dancing phosphor… the ears perking to the distant call of an unmet friend as yet another idea survives the smoke test and reinforces the reason for being.

Creativity can thrive anywhere — let it!

You must be logged in to post a comment.