Dataspace – The Essence of Disconnection

by Steven K. Roberts

Computer Currents

written June 4, 1987

published July 14, 1987

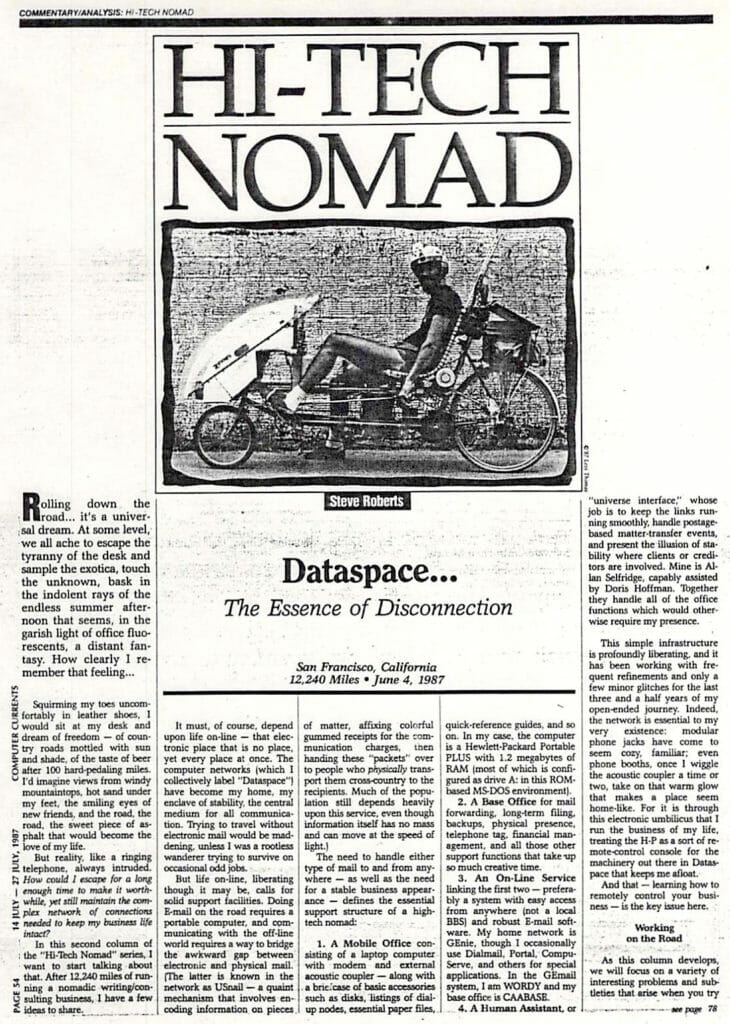

Rolling down the road… it’s a universal dream. At some level, we all ache to escape the tyranny of the desk and sample the exotica, touch the unknown, bask in the indolent rays of the endless summer afternoon that seems, in the garish light of office fluorescents, a distant fantasy. How clearly I remember that feeling…

Squirming my toes uncomfortably in leather shoes, I would sit at my desk and dream of freedom — of country roads mottled with sun and shade, of the taste of beer after 100 hard-pedaling miles. I’d imagine views from windy mountaintops, hot sand under my feet, the smiling eyes of new friends, and the road, the road, the sweet piece of asphalt that would become the love of my life.

But reality, like a ringing telephone, always intruded. How could I escape for a long enough time to make it worthwhile, yet still maintain the complex network of connections needed to keep my business life intact?

In this second column of the “Hi-Tech Nomad” series, I want to start talking about that. After 12,240 miles of running a nomadic writing/consulting business, I have a few ideas to share.

It must, of course, depend upon life on-line — that electronic place that is no place, yet everyplace at once. The computer networks (which I collectively label “Dataspace”) have become my home, my enclave of stability, the central medium for all communication. Trying to travel without electronic mail would be maddening, unless I was a rootless wanderer trying to survive on occasional odd jobs.

But life on-line, liberating though it may be, calls for solid support facilities. Doing E-mail on the road requires a portable computer, and communicating with the off-line world requires a way to bridge the awkward gap between electronic and physical mail. (The latter is known in the network as USnail — a quaint mechanism that involves encoding information on pieces of matter, affixing colorful gummed receipts for the communication charges, then handing these “packets” over to people who physically transport them cross-country to the recipients. Much of the population still depends heavily upon this service, even though information itself has no mass and can move at the speed of light.)

The need to handle either type of mail to and from anywhere — as well as the need for a stable business appearance — defines the essential support structure of a high-tech nomad:

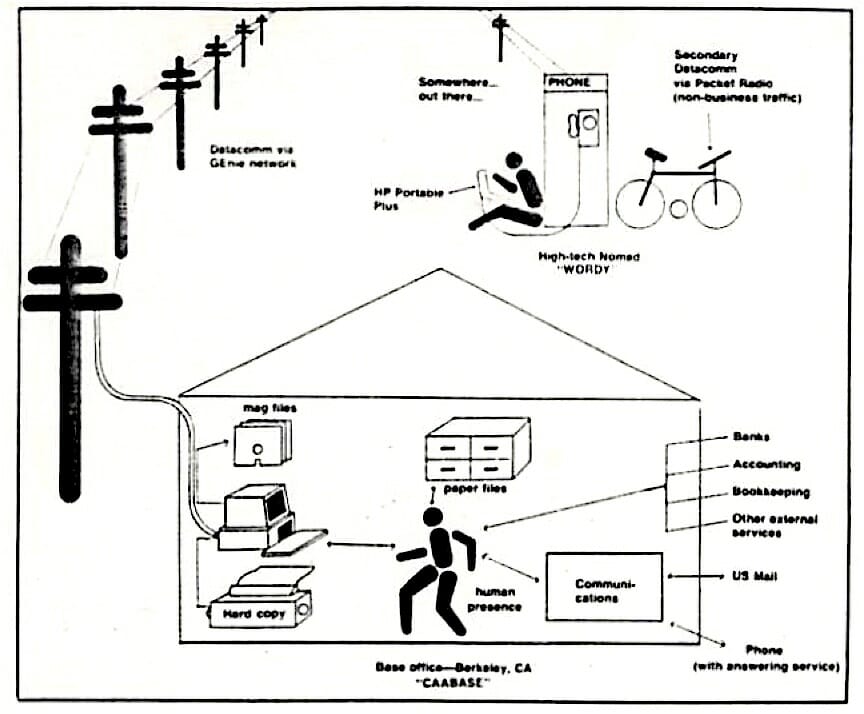

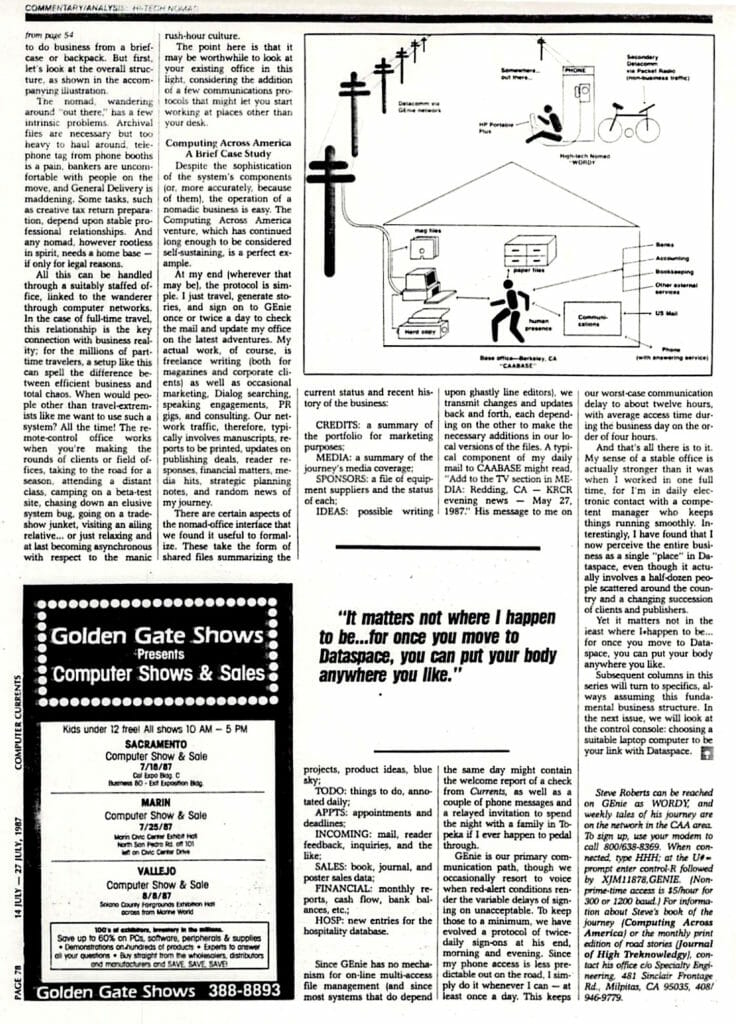

- A Mobile Office consisting of a laptop computer with modem and external acoustic coupler — along with a briefcase of basic accessories such as disks, listings of dial-up nodes,essential paper files, quick-reference guides, and so on. In my case, the computer is a Hewlett-Packard Portable PLUS with 1.2 megabytes of RAM (most of which is configured as drive A: in this ROM-based MS-DOS environment).

- A Base Office for mail forwarding, long-term filing, backups, physical presence, telephone tag, financial management, and all those other support functions that take-up so much creative time.

- An On-line Service linking the first two — preferably a system with easy access from anywhere (not a local BBS) and robust E-mail software. My borne network is GEnie, though I occasionally use Dialmail, Portal, CompuServe, and others for special applications. In the GEmail system, I am WORDY and my base office is CAABASE.

- A Human Assistant or “universe interface,” whose job is to keep the links running smoothly, handle postage-based matter-transfer events, and present the illusion of stability where clients or creditors are involved. Mine handles all of the office functions which would otherwise require my presence.

This simple infrastructure is profoundly liberating, and it has been working with frequent refinements and only a few minor glitches for the last three and a half years of my open-ended journey. Indeed, the network is essential to my very existence: modular phone jacks have come to seem cozy, familiar; even phone booths, once I wiggle the acoustic coupler a time or two, take on that warm glow that makes a place seem home-like. For it is through this electronic umbilicus that I run the business of my life, treating the H-P as a sort of remote-control console for the machinery out there in Dataspace that keeps me afloat.

And that — learning how to remotely control your business — is the key issue here.

Working on the Road

As this column develops, we will focus on a variety of interesting problems and subtleties that arise when you try to do business from a briefcase or backpack. But first, let’s look at the overall structure, as shown in the accompanying illustration.

The nomad, wandering around out there.” has a few intrinsic problems. Archival files are necessary but too heavy to haul around, telephone tag from phone booths is a pain, bankers are uncomfortable with people on the move, and General Delivery is maddening. Some tasks, such as creative tax return preparation, depend upon stable professional relationships. And any nomad, however rootless in spirit, needs a home base — if only for legal reasons.

All this can be handled through a suitably staffed office, linked to the wanderer through computer networks. In the case of full-time travel, this relationship is the key connection with business reality; for the millions of part-time travelers, a setup like this can spell the difference between efficient business and total chaos. When would people other than travel-extremists like me want to use such a system? All the time! The remote-control office works when you’re making the rounds of clients or field offices, taking to the road for a season, attending a distant class, camping on a beta-test site, chasing down an elusive system bug, going on a trade-show junket, visiting an ailing relative… or just relaxing and at last becoming asynchronous with respect to the manic rush-hour culture.

The point here is that it may be worthwhile to look at your existing office in this light, considering the addition of a few communications protocols that might let you start working at places other than your desk.

Computing Across America — A Brief Case Study

Despite the sophistication of the system’s components (or, more accurately, because of them), the operation of a nomadic business is easy. The Computing Across America venture, which has continued long enough to be considered self-sustaining, is a perfect example.

At my end (wherever that may be), the protocol is simple. I just travel, generate stories, and sign on to GEnie once or twice a day to check the mail and update my office on the latest adventures. My actual work, of course, is freelance writing (both for magazines and corporate clients) as well as occasional marketing, Dialog searching, speaking engagements, PR gigs, and consulting. Our network traffic, therefore, typically involves manuscripts, reports to be printed, updates on publishing deals, reader responses, financial matters, media hits, strategic planning notes, and random news of my journey.

There are certain aspects of the nomad-office interface that we found it useful to formalize. These take the form of shared files summarizing the current status and recent history of the business:

- CREDITS: a summary of the portfolio for marketing purpose;

- MEDIA: a summary of the journey’s media coverage;

- SPONSORS: a file of equipment suppliers and the status of each;

- IDEAS: possible writing projects, product ideas, blue sky;

- TODO: things to do, annotated daily;

- APPTS: appointments and deadlines;

- INCOMING: mail, reader feedback, inquiries, and the like;

- SALES: book, journal, and poster sales data:

- FINANCIAL: monthly reports, cash flow, bank balances, etc.;

- HOSP: new entries for the hospitality database.

Since GEnie has no mechanism for on-line multi-access file management (and since most systems that do depend upon ghastly line editors), we transmit changes and updates back and forth, each depending on the other to make the necessary additions in our local versions of the files. A typical component of my daily mail to CAABASE might read. “Add to the TV section in MEDIA: Redding. CA – KRCR evening news — May 27, 1987.” His message to me on the same day might contain the welcome report of a check from Currents, as well as a couple of phone messages and a relayed invitation to spend the night with a family in Topeka if I ever happen to pedal through.

GEnie is our primary communication path, though we occasionally resort to voice when red-alert conditions render the variable delays of signing on unacceptable. To keep those to a minimum, we have evolved a protocol of twice-daily sign-ons at his end, morning and evening. Since my phone access is less predictable out on the road, I simply do it whenever I can — at least once a day. This keeps our worst-case communication delay to about twelve hours, with average access time during the business day on the order of four hours.

And that’s all there is to it. My sense of a stable office is actually stronger than it was when I worked in one full time, for I’m in daily electronic contact with a competent manager who keeps things running smoothly. Interestingly, I have found that I now perceive the entire business as a single “place” in Dataspace, even though it actually involves a half-dozen people scattered around the country and a changing succession of clients and publishers.

Yet it matters not in the least where I happen to be… for once you move to Dataspace, you can put your body anywhere you like.

Subsequent columns in this series will turn to specifics, always assuming this fundamental business structure. In the next issue, we will look at the control console: choosing a suitable laptop computer to be your link with Dataspace.

Other articles in this series are also available here in the archive.

You must be logged in to post a comment.