Electronic monitors helping breed the cream of the crop

My mission as a USA Today columnist during the Computing Across America adventure was to report on interesting ways that people were using computers… and this one was more of a departure than usual from my technomadic and networking focus. I also wrote about computerized cows in a short Online Today article in early 1986.

by Steven K. Roberts

USA Today

November 15, 1984

YADKINVILLE, N.C. — Small farms, like the cream-topped bottles once left on back porches by milkmen making pre-dawn rounds, are slowly disappearing.

Now the early morning airwaves are abuzz with coded signals transmitted from cows frolicking in the pasture. They are unwitting accomplices in the increasing mechanization of the barnyard.

To a dairy farmer, a cow’s estrus cycle — the period she is in heat — is related directly to the bottom line. A farmer can lose more than $600 per cow per year by not keeping the animals optimally bred.

But since cows sometimes are in heat for only a few hours in the middle of the night, some farmers have had to hire “heatwatchers” so that artificial insemination can proceed without delay.

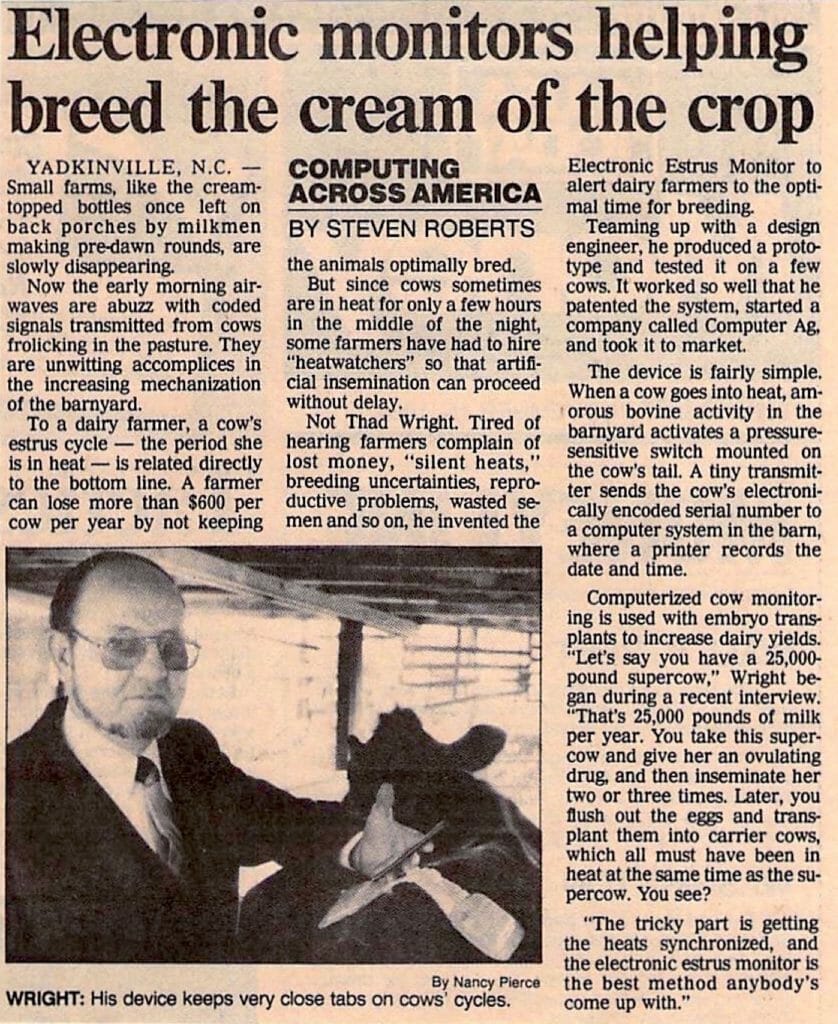

Not Thad Wright. Tired of hearing farmers complain of lost money, “silent heats,” breeding uncertainties, reproductive problems, wasted semen and so on, he invented the Electronic Estrus Monitor to alert dairy farmers to the optimal time for breeding.

Teaming up with a design engineer, he produced a prototype and tested it on a few cows. It worked so well that he patented the system, started a company called Computer Ag, and took it to market.

The device is fairly simple. When a cow goes into heat, amorous bovine activity in the barnyard activates a pressure-sensitive switch mounted on the cow’s tail. A tiny transmitter sends the cow’s electronically encoded serial number to a computer system in the barn, where a printer records the date and time.

Computerized cow monitoring is used with embryo transplants to increase dairy yields. “Let’s say you have a 25,000-pound supercow,” Wright began during a recent interview. “That’s 25,000 pounds of milk per year. You take this supercow and give her an ovulating drug, and then inseminate her two or three times. Later, you flush out the eggs and transplant them into carrier cows, which all must have been in heat at the same time as the supercow. You see?

“The tricky part is getting the heats synchronized, and the electronic estrus monitor is the best method anybody’s come up with.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.