The Price of Adventure

Computing Across America, chapter 45

by Steven K. Roberts

St. George, Utah

November 10, 1984

We have to endure the discordance between imagination and fact. It is better to say, “I am suffering,” than to say, “This landscape is ugly.”

Simone Weil

I finally found the true meaning of desolation.

Early in the journey, I naively thought it referred to the coastal plains of the eastern United States — those endless miles of marsh populated by stick-legged birds and slithering reptiles. I later revised my definition to include the vast dusty stretches of west Texas. Still other pockets of desolation have appeared here and there in my travels — some of them cultural, others internal.

But between Colorado and California, desolation is the rule rather than the exception. That challenged the very motives behind the trip (and made the exceptions seem sweet indeed).

The first clue appeared a few miles west of Green River, Utah, in the form of an understated sign on the interstate:

NO SERVICES

AVAILABLE ON 1-70

NEXT 100 MILES

I stopped to ponder the implications of this, with particular attention to my sixty-ounce water supply. Hmm…

That’s 1.2 tablespoons per mile.

I took a tiny sip and pressed on. Something would turn up. Something always does.

But the first thing that turned up was the road. I began a long climb, mile after mile on an endless highway of semis and campers, sweating in my bunting through cold air crackling with CB chatter. The morning had started at twenty-two degrees, and I hoped I would find a place to sleep before it got back down there. There was a strange fatigue gripping me.

Up. Up. No big deal, really — grades on interstates are never very intense, but they’re quite capable of going on forever. When I finally crested the San Rafael Swell in the early afternoon I was only about thirty- five miles along… and already out of water.

“Ah, breaker there, westbound motorhome,” I said into the microphone.

“This is that bicycle you just passed. Gotchyer earzon?”

“Ten-four, bicycle. You sure picked yourself a lonely piece of highway to ride.”

“Yeah, I get that impression. How’s it look from here to Salina — does it flatten out any?”

“Well now, you’ll be up and down for a good ways, then you have one big climb to eight thousand or so. But the last twenty-five miles is all downhill.” I glanced at my digital clock. Almost 2:30. “Looks like I’ve got a night ride coming up, eh?”

“Ten-four on that. I sure wouldn’t do it. Hey, do you need anything?”

“Well, as a matter of fact, I’m out of water.”

Far ahead, on a long sweeping leftward curve, the brake lights of the motorhome immediately flashed red. We continued chatting as I approached, and by the time I panted to a stop behind them we had swapped the essential details of our travels — they were a retired couple from Salt Lake City taking their plush new Coachmen rig on a shakedown cruise.

Water: one of those things you don’t appreciate until you lack it. I knocked back a jugful and refilled the bottles, then packed their gifts of sandwiches, pickles and fruit onto the bike. The kindness of the Tuckers nourished me for days in this desolate land.

Onward. Up and down, rugged, empty, huge, brown, sage, desert, a vast nothingness highlighted by crazy rock and deep valley. Any one of these countless hills would be legendary in Ohio. It went on, hour after hour, and I now understood the comment of the old Memphis women in Grand Junction.

But this wildness would probably have enchanted me had it not been for something that wasn’t Utah’s fault at all: the depressing recognition of an illness beginning — fever, weakness, a hint of congestion. Oh no, not now. Please…

At dusk I started the climb — an eighteen-mile uphill in subfreezing wind. I tried to ignore my throat, each swallow a little more painful than the last. Sore and out of shape from the long Telluride layover, my joints feeling the fever, I pumped grimly, numbly. My clothing was sweat-soaked, the water supply failing again. I wanted a stillsuit, for I was squandering my most precious commodity in the form of sweat.

Granny gear, darkness, the mile markers passing at the rate of one every twenty minutes. I had plenty of time to watch each approach and ponder it — sometimes I’d see the little green glint in the far-off light of a passing truck and count the pedal strokes, slowly, slowly. I shined my flashlight at the altimeter, trying to celebrate every increment on the dial but chilled by the realization that there was a long, long way to go.

Passing truckers on the CB were concerned enough to abandon their usual bemused reaction to my presence. “If you can make it to the eighty-yard line, rider, you’re home free — it’s downhill from there on into Salina.” I pushed ahead, almost delirious from exhaustion.

There I go, doing it again. Have I no sense? I pulled off at a ranch exit, determined to camp. I was so weak I almost fell over, bike and all; trying to stand hurt so much that I lay down immediately on the cold concrete to rest.

Twenty-six degrees and dropping. My intestines seemed ready to explode; my breath burned hot on my hand. Whimpers. So alone… so terribly alone. I should be in bed, chicken soup, Sylphide, music, mother putting Vicks on my chest, thermometer under the tongue three minutes, Steve? Steve? Can you hear me? Should I call the doctor?

I turned my head to the side, red ear scraping icy gravel. The yellow blinker was still on. I tried to lift an arm to the switch, leaden, numb fingers. It failed, fell into the spokes, lay there cold, little whimpers, distant truck noises. Oh no… not diarrhea… not that too! I staggered to my feet and hung my ass over an ice-cold galvanized guardrail, balls stuck to freezing steel, no paper, the bike absurd and ridiculous out here in the middle of fucking nowhere, Utah. Great. Just great.

Now what? Camp with no water? I shivered, deep shivers from way down inside. Clothes damp, frost touching things around me, little sparkles of moonlight on the sparse grass, the soiled guardrail. I staggered around lost. Camp? Camp? I tried to imagine pitching the tent… maybe if I just take a quick nap…

I collapsed and curled into a fetal position, sharp gravel under my head. No. I’ll die. I stood again and fumbled through the packs for more layers, more shirts, anything. All of it, dirty stuff too. Boots, gloves, balaclava, bundled bulky like a kid sledding.

Onward. Just a few more miles. A few more hours.

Moon misty in an advancing front. Temperature near 20°, fevered breath hot in the silk, sphincter gripping, gasping coughs. Every mile marker a small victory, a moment of reassurance. Countless confused calculations in my head, anything to distract me from the pain. I can’t feel my burning cold feet…

Mile 80.5 at last! I had reached the summit, 8,000 feet from the morning’s 4,000. I dismounted and stood unsteadily in the empty night, flashers reflecting eerily from roadside snow. It would take nearly an hour now to coast the last twenty-five miles to Salina — a seeming dream after the day-long struggle, but wind-chill… the equivalent temperature would average 18 below zero, whistling through sweat-soaked clothing to my damp feverish flesh.

Cold, cold, cold, snow on the banks, tires rushing, trucks changing lanes, ears popping. Deep chill, violent shivers, insane grins, teeth frozen, all lost in the blast of wind. Headlight off to save the battery. If I’m going to kill myself, it might as well be with dramatic intensity. A deer bounded away as I flashed past; another, gruesomely mangled and bloody wet in the road, nearly felled me. I slid with a shout through the fresh carnage of a world-class road-kill, certain that my own body would be next.

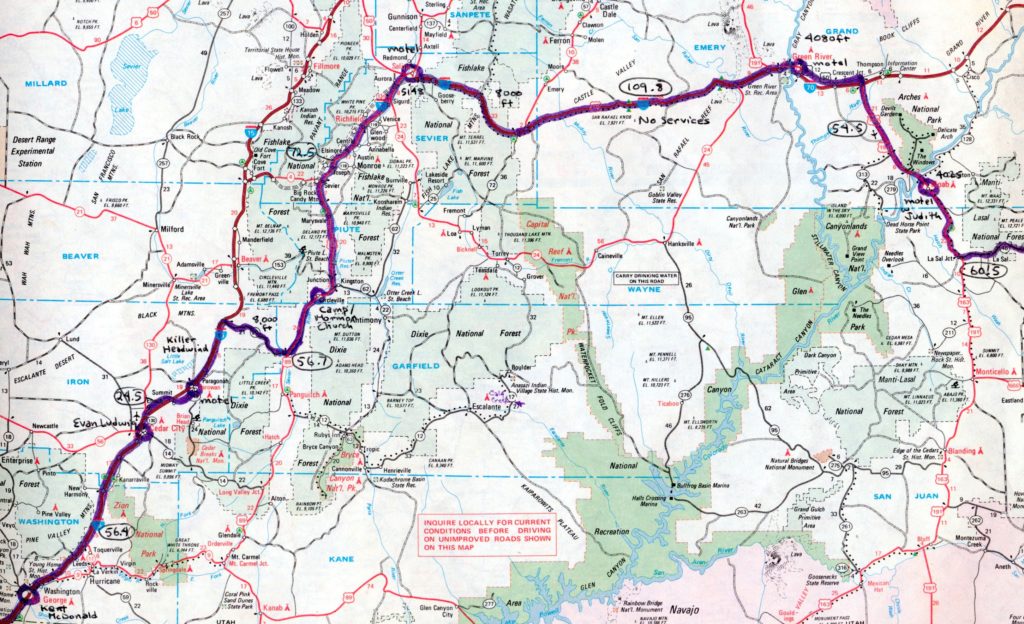

Lights! Salina — Goddamn, I did it! 109.9 miles. I rolled into the Safari Motel at 9:45 and stumbled victorious into the lobby, blinking at the warmth and light of civilization, smiling at the dour old guy at the desk as if he were a long-lost friend.

He looked at me with hostility and said I couldn’t take “that thing” into the room.

I rolled down the street to the Best Western and collapsed. Thinking that matters could get no worse, I switched on the TV.

Reagan won the election. I ran to the bathroom.

Sicker, I pressed on. I had six days to make it to Las Vegas for the COMDEX computer show, but I figured the worst was over.

Wrong.

I headed south from Salina, the land nondescript at first, then beautiful in places. But the wind was from dead ahead and the people were cold and distant, slightly curious but remote. Not hostile, not welcoming. Not anything — just dull. I rode on, passing now and then through a town, looking for a motel, finding at last the only one for thirty miles in Circleville.

No vacancy.

I was out of tissues, a soggy knot of them fused cold in my pocket. Dizzy from fever and exhaustion, I found a cafe and settled into a hamburger, hoping the bike would spark interest. Rarely does it fail to draw a crowd. But people looked, shook their heads, and passed on; the men in the cafe asked a few perfunctory questions and went back to their coffee. I probed what I could find of the town and found no warmth. Some people were superficially friendly, some were macho-tough-remote, all were unsympathetic. Even the women. Mormons, eh?

Grumbling and cursing Utah, I pitched camp in the lee of the church, dropping sore and empty to lie puddled in mucus, noisily breathing orange clouds in the tent-filtered glow of sodium-vapor streetlights. I sought solace in West-coast AM radio stations (Wow… California…) and finally managed to doze, lying in sweaty clothes inside my inadequate 20° down sleeping bag.

Uh-oh.

I woke, held my breath, blood cold, fear gripping me. A motorcycle idled only feet away, its headlight vibrating on the tent. My nose was filled with concrete and I tried not to swallow; stealthily, I grabbed the flare gun and unzipped the door an inch. I peered out.

The biker sat regarding me through the inscrutable shield of his faceplate. He switched off the engine and sat a moment, then removed the helmet and dismounted. I relaxed slightly.

“Hello?” I called, in a voice friendly but very much unlike mine. I tried again to sniff.

“Hello?” he replied. He was the Merrill, the church custodian, a kind old man who watched with concern as I talked and coughed and snuffled. I did the basic show-and-tell; he told me of Mormonism. “Do you believe in the Scriptures?” he asked.

“Oh yes,” I rep-lied, sensing the gradual opening of a Circleville door. My moustache was frozen from the uncontrollable nose, and he smiled, shaking his head.

“I might be sticking my neck out here, but don’t you think you’d be more comfortable inside?”

I wanted to kiss his hands. “Ohhh, yes…” He helped me break camp and carry things, explaining the church all the while, urging silence (a Relief Society meeting was going on in another part of the building). And suddenly I was surrounded by folding chairs and green carpet, armed with a whole roll of toilet paper, dulled by the hum of fluorescent lights.

I stayed quiet and concealed until midnight — until I could be sure the last of the Relief Society members had left. Didn’t want to be caught trespassing by folks who dedicate themselves to providing assistance to those in need. Actually, this is a respected part of Mormon society, helping people cope with everything from childbirth to natural disasters, sending food, money, and help wherever needed. Perhaps they would have leapt at the chance to rescue a fevered traveler on their doorstep… but as an outsider, I had been advised to take no chances.

Sleep was a disaster, but at least I could be sure the worst was over.

Wrong again. I continued south, my Mormon friend bidding me Godspeed in a voice full of genuine concern. The headwind was worse, my illness was worse, and new snow lay on the mountains.

This day had three phases, each more brutal than the last. Under a sky the color of cold-rolled steel I fought my way south to the 89-20 intersection, anticipating another climb to 8,000 feet. At a food, rock, gas, and antique shop I stopped to drink soda and ask advice, and the old couple flatly told me that I would be crazy to cross the mountains. The man pointed out the window at the road west, a winding black thread disappearing up the wall into dark storm clouds. Eastbound autos had their lights and wipers on.

Phase two. West. A 1,500-foot climb into the wind, blowing snow, dark sky, incredulous drivers. The summit… rugged vast beauty I could almost appreciate. The descent… into hard blustery wind that demanded careful control and created a whole new problem: With a congested head, the rapid 3,000-foot drop turned my eardrums into aneroid barometers, a pair of daggers inexorably pressing into my brain, their points nearing, nearing…

Phase three. South again, Interstate 15. It was only sixteen more-or-less level miles to Parowan, but it took almost three hours of battling into a gale so bad that a barn blew over in Paragonah as I passed. The frustration and anger finally reached a peak; the relentless abuse of three days was too much. With nowhere to stop and no option but to press on into stinging salt storms and cold black skies, my rage emerged. “Fuck Utah!” I cried over and over, giving the finger to the hostile land, the wind, the sky, the road, the mountains, all of it, every acre of it. The eccentric beauty of Arches seemed impossibly remote, not the Utah I had spent three days battling.

But then another Best Western motel. Ah… the lady knew me from TV, fired up the Jacuzzi, sent me to the Swiss Village restaurant for an excellent German dinner, and smiled.

And this time, the worst really was over. I slept hard.

Breakfast. There was a sign on the counter in Parowan’s Pit Stop restaurant: “We will not be responsible for injury to any child that is not kept in their chairs at the tables.” Chuckling at the language, I took a picture — whereupon I was sternly informed that the owner does not allow picture-taking. Utah is so strange.

On to Cedar City. After three and a half congested days in grim desolation, the sight of twenty-three grinning people standing immobile in a computer-store parking lot was odd enough to justify a stop. They were in an area bounded by colored flags, just standing there, resting their hands on Apple //C boxes.

“Uh, hello?” I called, pulling alongside the strange spectacle. Was this a meeting of a computer club? Nothing would surprise me in Utah.

They smiled and asked about the bike, but nobody moved. Though their hands seemed glued to the computer boxes, they didn’t seem to mind. I could detect no demographic clues — ages ranged from about twelve to at least thirty-five. Something seemed vaguely festive about it all, and I heard one lady say she had reserved a babysitter for three days.

The crowd laughed at my confusion, and someone finally explained that it was a contest hosted by Personal Business Computers: the person who could stand there the longest without letting go of a computer box would win an Apple. It was noon on Friday — they had just started. Hence the smiles.

I later learned that the winners endured subfreezing sleepless nights and exhaustion for sixty-three hours. The company called a merciful halt and gave away two computers at 3 a.m. on Monday. I tried to imagine the bitter struggle between these two women, both die-hard computerphiles, glaring at each other in the frozen dark as the contest turned ugly, lusting past their misery for that wonderful little machine.

Somehow, it sounded familiar. Utah was a land of difficult marathons.

I stayed in Cedar City with the owner of the Swiss Village restaurant, got a free haircut from the Hair Lab, jammed flute and guitar with the stylist, made jazz tapes, and wrote a USA Today story about computerized cows. A notable improvement. Fifty-six mostly downhill miles landed me in St. George, where I hoped to meet the helicopter-towing lady with whom I had breakfasted six months earlier in Ponchatoula, Louisiana.

But it was her friend, Dr. Kent McDonald, who took me in and added human warmth to my memories of Utah. His family was close, cultured — with two wonderful little girls, a laserdisc stereo system, a Tour Easy recumbent like Stacey’s, and a cello on which he played the delicious Zoltán Kodály sonata in B minor. The Color Country Wheelmen threw a pot-luck dinner for me, and it finally began to seem a different Utah, a hospitable one, even a friendly one. The elevation was 2,760 feet, the lowest I had been since Texas, and green suburban lawns were edged with flowers and shrubs.

Kent rode south with me through the Virgin River Gorge of northwest Arizona, then I continued alone to a zoo within a zoo, a place of high-tech glitter amidst madness, something so much unlike the surrounding lands that it now seems as much a dream as the magical Arches interlude.

You must be logged in to post a comment.