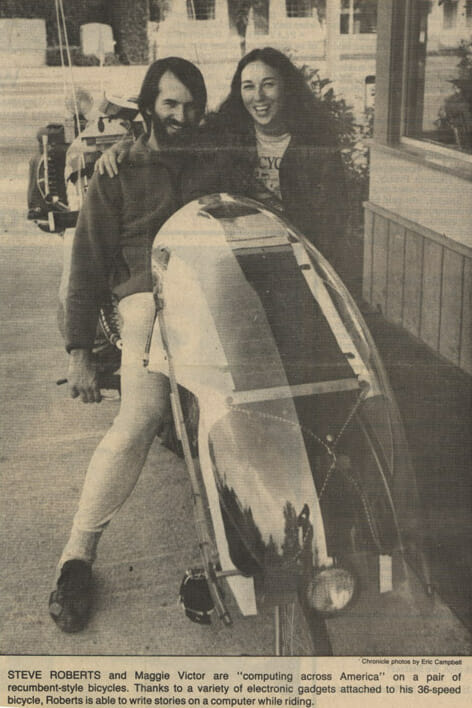

Flying on the Coast

by Steven K. Roberts

Lakeside, Oregon

November 12, 1986

It had to happen eventually. Things have been easy too long; riding south in the Willamette Valley, even when wet, was flat and easy. But from Eugene, every road led skyward — east into the Cascades, south into the Siskiyous, or west into the Coast Range.

Naturally we opted for the Pacific coast, that 2,000-mile cycling bonanza that attracts travelers from the world over. Good shoulders to fly on, cheap camping, friendly hostels, bicycle-aware drivers, a mobile community of cyclists, classic scenery — all this and more defined the Pacific coast route as the way to continue south. But first… we had to get there.

“You’ll be needing these,” said Laura, handing us two dozen homemade chocolate chip cookies, still warm. Outside, the drizzle was starting — though we managed to convince ourselves that the occasional patch of less-gray sky meant sunshine ahead.

Eugene had been a delight, yet another of those potential homes characterized by intelligent people, surprising resources, and quick new friendships that seemed already timeless. Laura and Jim were kindred spirits: veterans of long-distance cycle touring, bright and playful, happily living freelance lives asynchronous with the business world. Staring out at the rain amidst the laughter of my new friends, I was in no mood to hurry.

But southbound we must be, for it is November and this is Oregon. We took a last gulp of coffee and hit the road.

It took but a moment to sense the difference. This was not to be a lazy ride, like most of the ones since Seattle. My altimeter advanced slowly as I sweated in the polypropylene cocoon, rain pattering Gore-tex, wind whipping flags — occasional misty vistas on the switchbacks recalling other mountain moments, other rides, other epochs. 1200 feet: not much, really, but there would be four such climbs in the 96 miles to the coast — 96 miles with no services, no water, and only primitive camping. I rationed myself a small sip and pressed on, sharing radio reassurances with Maggie, pointing out the sights, topping the first hill easily enough and coasting into the Coast Range—further from people and food and network nodes… and everything else that comforts the wanderer.

Onward. Into the folds of hills, a labyrinth of valleys, a wonderland of woodland. We would round bends and find the devastation of a fresh clear-cut, suffer through it for a mile or so, then cross a BLM boundary and find ourselves once again among 5-century-old firs. Clear-cutting makes sense, they say: the theory is to harvest a forest, replant with efficient new hybrids, then tear it all down again in 30 years or so. NEW FOREST PLANTED SPRING 1986 proclaimed an International Paper Company sign… neglecting to note that the old forest, grand and diverse, was destroyed in the fall of 1985. Only the remnants of a slash-burn, punctuated by black stumps and orange ribbons, remain as a cynical monument to what once was a place of beauty.

But there’s beauty around here too, lots of it, whole valleys shrouded in mist and echoing with the muted calls of birds. Trees peek through clouds in disembodied mystery, roads twist like rogue capillaries among disorienting hills, deer flash through clearings, thick moss coats riverside trees like green day-glo flocking, leaves drift across the rainy road and land among their fellows in heavy silence. Fishermen stand knee-deep in rapids, hunting salmon; odd botanical curiosities never seen in the east draw the eye with their lush eccentricity.

Delighting in all this, we failed to notice the early dusk.

Camp, primitive style. There was evidence of a previous fire, only that — no showers or picnic tables or campground stores. No other campers, either, nor any nearby settlements. There was, however, plenty of waterlogged mossy firewood… as well as rain, cold, sore throat and fever. Not good timing.

Maggie set to work on dinner, one of those camp glopolas that would be ho-hum in suburbia but seems magnificent in the wilderness. I shoveled it in, seeking warmth as well as nutrition, feeding my face with one hand and the tentative fire with the other. Soggy sticks hissed and smoked; Lexan spoons clinked stainless pots; wet clothing steamed; the swollen river rushed in the background. I shivered, snuffled, huddled to flames, sipped hot cider, and tried to ignore the fever symptoms… for we were in that vague region lying between recreational camping and survival. When I dove into the tent and clung to my lady for warmth, I had a whole new reason to appreciate NOT traveling alone.

And it was a long night — 14 hours of darkness and rain, confused dreams and pain; then came a gray dawn of biting cold and heavy condensation. This is the true test of gear, and the deficiencies quickly became obvious. The Kelty tent, chosen for its size and not its quality, soaked through and dripped. The waterlogged $110 Gore-tex rainsuit never dried out (On the second day, I found a plastic laundry bag with holes for head and arms to be more comforting). My new $25 neoprene gloves “for all wet-weather cycling” needed to be wrung out every few minutes, and a pair of special gaiters made for cycling not only didn’t fit, but fell apart and soaked my shoes as I rode. How is it that gear designed for heavy weather fails under stress, while “delicate equipment” like the HP computer and Yaesu radio press on unaffected, even when it’s so humid that they have to be wiped dry every few minutes?

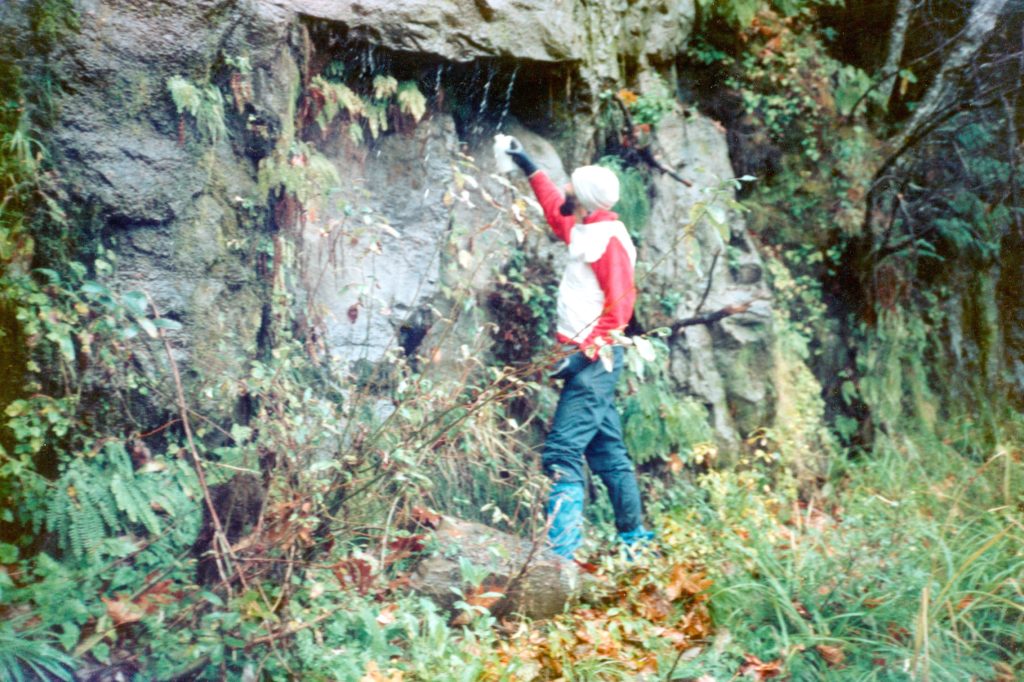

Day 2. One big climb, sweating away the last of our water with 56 miles to go. The mud puddle tasted pretty good, and the runoff down that mossy cliff was so delicious that we filled all our bottles and pretended we’d never heard of Giardia. We ate the last cookies while gazing out over miles of misty wilderness, then flew, freezing, down a thousand feet and pedaled until dark along the sinuous Smith River valley, back and forth, our view slowly broadening until the bright sky and blazing sunset bespoke Big Water — the ocean — the Pacific at last. Weak and wheezing, I managed the last few miles into Reedsport and settled into the Western Hills Motel… surrounded by soggy high-tech fabrics and the roar of Highway 101.

And so begins a new phase. Now, two days later, I write in the guest room of our new hosts, new friends again. The cycle repeats with all variables changed; the lifestyle sampler has turned up yet another treat. This time: atypical retirees (neither snowbirds nor sedentary) building a sleek amphibious airplane and living for the joy of flying. Howard is recovering from the brief setback of triple bypass surgery last month (you can’t tell); Barbara does the epoxy and fiberglass work on the plane and is a lively, thoughtful hostess. Their friend Eric whisked us around Tenmile Lake at sunset this evening, speeding across the rippled reflections of mother-of-pearl sky colors and autumn shoreline, the wind in our hair, broad grins frozen on faces recently locked in groaning granny gear grimaces. I’m fantasizing about my third journey already — in a computerized seaplane. And we’re living yet another in an infinite succession of glimpses into lifestyles ranging from the bizarre to the sublime.

There are so many ways to live…

…and I want them all. Why commit yourself to the cherries jubilee when you can wander freely in the kitchen?

You must be logged in to post a comment.