1909 Great Loop Adventure – 1 – Retrospect

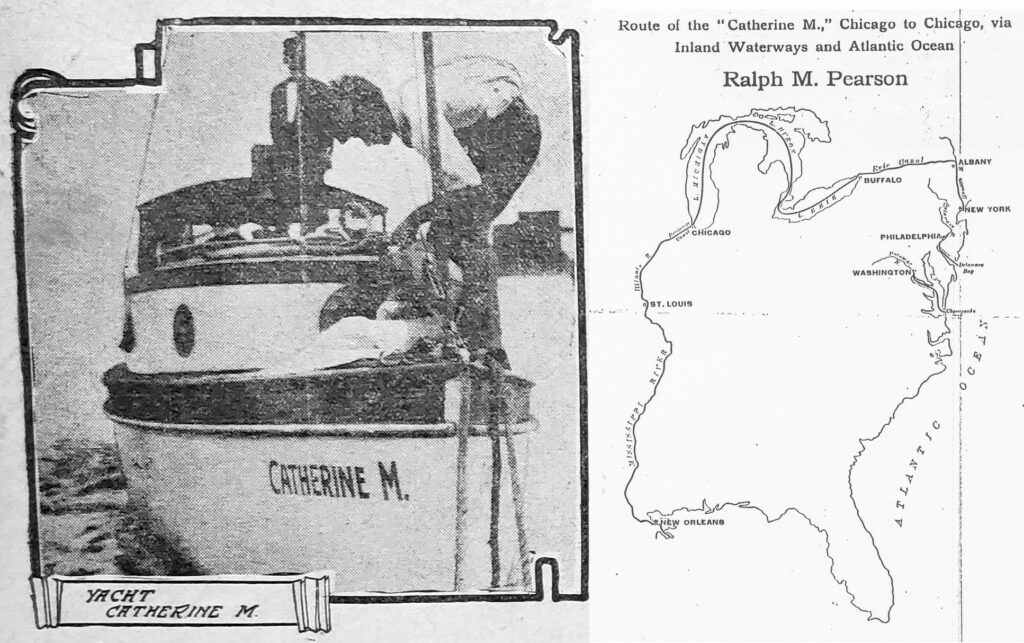

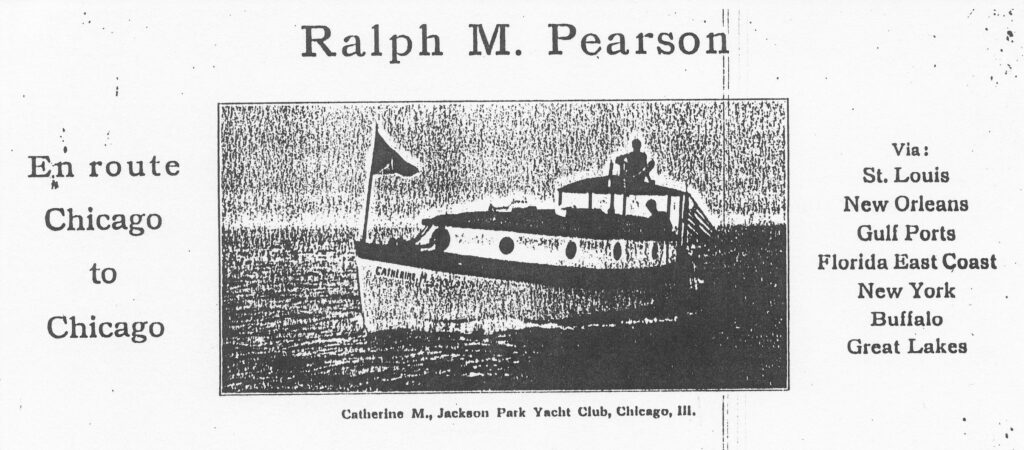

This marvelous text is by Ralph Pearson, my biological grandfather, who embarked from Chicago on an epic Great Loop voyage on May 3, 1909. There is a newspaper article from a couple of weeks later that gives a bit of an overview, but his unpublished book about the adventure begins here:

Retrospect

by Ralph M. Pearson

May 3, 1909

I lean back in my chair. The work on my study table is forgotten as I fall to dreaming again of that never to be forgotten six months afloat. Moving pictures of scenes, places, and action focus themselves on the screen of my memory, flicker a moment, and then are crowded into oblivion again by the press of those succeeding. The warm cozy room fades. The light at my elbow changes to a binnacle. I am at the wheel again in the midst of the wild black turmoil of the storm. Involuntarily I steady myself against the violent rolling of the boat. The wind shrieks through the rigging and tears at the cockpit curtains; the maddened seas leap out of the blackness ahead and smash cruelly at the laboring ship. Huge wings of phosphorescent spray drive aft like a thousand hailstones, and I gasp for breath as I duck into it. The light of the binnacle glistens from dripping oilskins, and faintly shows the straining curtains against the black terror of the night outside.

The picture fades and I see the pale blue waters of the Atlantic Ocean gently lapping the stones at my feet, while the bright, hot sun of the tropics bathes a coral island in its midday heat. Fred, with the pike pole, is hooking huge green coconuts from a palm-tree overhead, and as they drop I am gathering them into piles to carry back to the boat where Mother is waiting for the first taste of the fresh milk. I see him chop the first one clear in two with the ship’s hatchet, and I hear him swear impatiently because the milk runs out.

The coral island changes to a wide sweep of salt marsh with the low red mud banks of a narrow Georgia creek still wet from the falling tide, and the marsh grass waving in the breeze. The boat is monotonously creeping along (northward now), when suddenly the stern wave begins piling up behind, showing shallow water, and before I can throw the reverse lever she is scraping bottom and is stuck. I can see it all as plain as though it were still happening before my eyes–the quick throw of the stern line, the propeller, full speed reverse, churning the muddy water into foam, the back breaking push on the pike pole, till at last she gives and is free again.

A jump of a thousand miles and we are passing under a railroad bridge out from the mouth of a river into a large spreading bay with the roll of the ocean coming in from the east. There is a grey misty half rain in the air, and the clouds overhead are low and threatening. Powerful tugs, like bull-dogs with big white bones in their teeth, hurry past us. To starboard a steamer, red grey in the fog, is slowing, against the tide, picking her way among the shipping out to sea. Deep throated whistles boom port and starboard to each other and to the shriller whistles of the many tugs. Into the smoke and mist to the westward we are gazing intently, waiting for some expected shape to form itself into reality. At last we can make it out. Yes there it is, stronger and clearer, the sight that we have looked forward to for months, wondering if we would live to see it, the sight that has cheered countless thousands of Americans, the Statue of Liberty.

The tumbling rock walls of the Hudson pass rapidly in review and change to the green rolling hills and the straight level banks of the Erie. Now we are tied to a coal dock in Buffalo waiting for better weather to try the lakes. Now we are pitching and pounding over the treacherous seas of Lake Erie forty miles from shore, and again the cold sweat starts out all over me as I remember the discovery of the leak and the water all over the cabin floor, and the spray flying from the engine flywheel. Again I am bailing for our lives and wondering whether I can make a raft when the worst happens, or whether we will have to go down into the cold water with the ship.

I see friendly life savers making us welcome at their lonely station, the children bringing fresh milk and new picked garden stuff for presents. Again the black clouds are banking up ahead, and the freshening wind is throwing the spray higher and higher, as we run, like a frightened rabbit, for the lee of that low green island off the port bow. And as we gain its shelter, I am again picking my way inshore over a boulder-strewed bottom till we gently rub the beach and wade ashore to explore the wonders of a deserted island.

Now the red tower of a light-house, with its winking light partly dimmed by approaching dawn, is dropping astern and again I am tense and alert as the thick fog blanket rolls around us blotting out the light and the distant shore line to the north. I am shutting the cabin doors and hatch to subdue the noise of the engine, and, trusting to compass and chart, I am steering into nothing, listening intently for the warning signal of some steamer which imagination constantly pictures looming out of the fog to run us down.

Now follow the long, grinding all-day runs over gently heaving, sunlit seas, past strange shore lines and islands, each headland, each point, each harbor foretold by the chart in front of me, and eagerly watched for and recognized, till at last, with a tumult of emotion, we see the dear old Chicago Light grow from nothing into reality, and, rounding the breakwater at the river’s mouth, we are “HOME.”

The unusual is interesting. I have been home from our trip six months and the wonder of it has not worn off nor the memory dimmed. I had not supposed it would be of particular interest to others, but I find that the same love of the outdoors and of boats and of water which impelled me to make this trip, also impels many of my friends to dream of it and to wish that they could take it too. And many to whom it seems most alluring, are the ones who do not own a boat and who have had no experience on the water. So if I can dream and ramble again over those six thousand miles of changing scenery, and paint with clumsy words some of the pictures which change a map from a sheet of flat paper to a living scene, a printed coast line to a long stretch of foaming beach broken here by the battered hulk of a four-master thrown half way out of the water by the sullen power of those long green rollers, then I may be able to feed their imagination to a point where they too can see something of these pictures and gain a pleasure therefrom which they would otherwise miss. Then again, someone is now planning this trip, and some else may feel the pull of it and decide to try it. These might gain something from the experiences of another that would save them trouble or disaster by a more intelligent preparation. It cannot be denied that there are many perils and dangers which must be foreseen and provided against, and that they have a way of presenting themselves in a most sudden and unexpected manner, so that one must do the right thing instantly and surely or pay the forfeit. And as Nature plays no favorites and gives no quarter, the forfeit may be death. There comes the sudden cry, “Rocks dead ahead!” Hard-a-starboard! The order has flashed from mind to hands; the wheel is hard over; you now see that if you had turned to port you would have crashed into a mass of them. You made the right move and your boat is still under and the waters make no outcry, they only wait.

Your engine suddenly stops as you are passing out of harbor on the weather side of a long breakwater with a stiff sea driving inshore. You try frantically to start it. No use. The boat is driving straight for the pier, rolling helplessly. You shout to a fisherman on the pier to catch your line. Your anchor line is coiled perfectly on the forward deck. Hanging to the forestay with one hand, you coil the line in the other. When the right instant comes, you put every ounce of your strength in the throw. For a nerve-wracking instant the line uncoils itself across that dread chasm of hungry waters, then–falls true. Willing hands grab the line and pull you down the pier to safety. You have won again. No time nor quarter for mistakes. If the line had not been properly coiled you would have lost, for it would not have paid out for a long throw. And so it goes.

We had prepared the Catherine M. for her trip as thoroughly as we knew how. Most important were the reserve parts. Two independent gasoline tanks were connected separately to the engine, one holding seventy gallons and placed under the forward deck, and one holding sixty gallons placed under the cockpit floor. There were three different electric systems, cockpit control of engine and reverse, electric and oil lamps in binnacle and engine room, two anchor lines both coiled on deck ready for instant use, a small sail for emergencies, two fresh water tanks, one small portable one to stand over the sink, the other holding thirty gallons for a reserve supply when at sea. To the efficiency and readiness of several of these reserves, we, without question, owe the fact that we are today among the living.

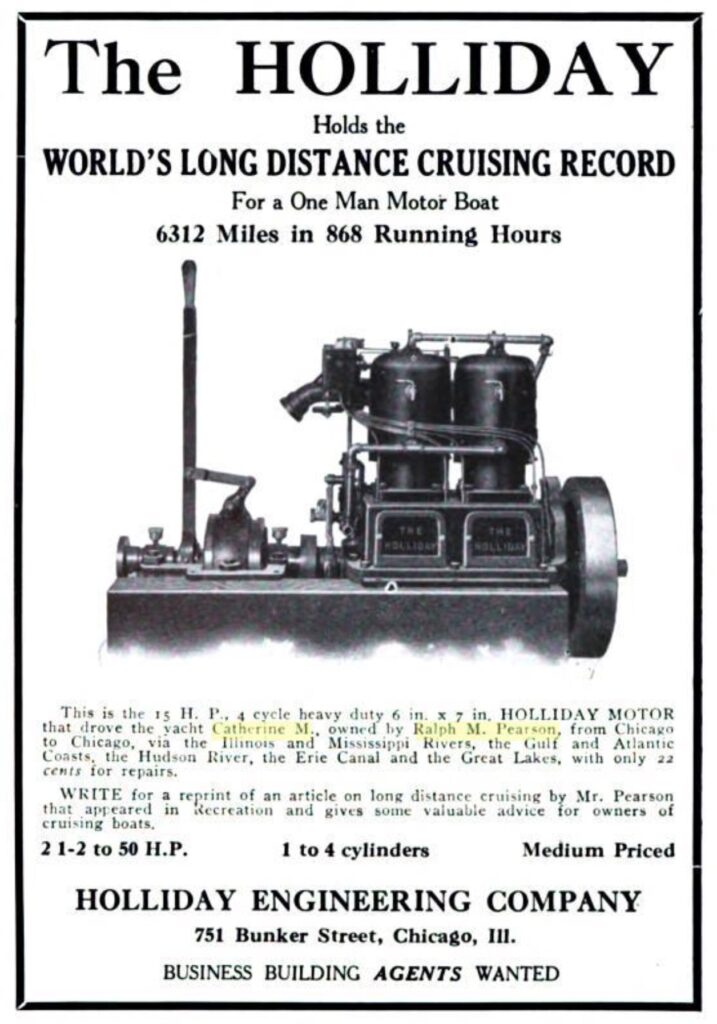

The boat was thirty-five feet over all, eight feet beam, three feet draft. She was the trunk cabin type with self bailing cockpit enclosed with curtains on three sides but open forward. There were two bunks in her thirteen foot cabin forward and one in her seven foot engine room. Separating cabin and engine room was a clothes closet to port and a toilet room to starboard. The galley, on the starboard side of the engine room, included a small sink with hand pump connected outboard, a dish locker and a one burner gasoline stove (which was much too small). The engine was a 15 h.p. four cycle, heavy duty Holliday, tuned up and in perfect order for its long grind. Shaft and wheel were of bronze for salt water, but the rudder and all fastenings were of galvanized iron which three months of salt water had not damaged. She carried a detachable signal mast forward and flew the burgee of the Jackson Park Yacht Club from her starboard yard arm.

For personal preparation I had taken a course in navigation with the late Lt. Wilson of the U.S. Hydrographic Office in Chicago which if I had had three years of experience instead of one, would have entitled me to pilots’ papers for lake Michigan. I had learned how to plot a course, correct compass for deviation and variation, adjust compass by swinging ship.

I knew all pilot rules, fog signals, buoys, etc., knew something of azimuths and observations,, could take compass bearings of distant objects, etc. While this was only a beginning in this most fascinating subject, it was enough to give me a certain confidence in my ability to meet the emergencies as they should arise.

I started the trip with a tender, but lost it ten minutes later in getting out of my home harbor at Jackson Park. An ugly and unexpected cross sea snapped the painter like a piece of thread and the tender went ashore and I, taking the lesson to heart, went on without. We made the entire trip without one. This was undoubtedly a dangerous risk to take but even if we had obtained another small boat there were at least four times when we would have lost it.

The crew consisted of my mother and myself as first mate and captain (I was captain, that is, technically and in matters nautical) and of Fred Gurley (appropriately named as I found later), a hunky looking young physical culture student whom I had picked up at the last minute for general handy man.

I had worked hard for this trip and made sacrifices to bring it about, but I felt that I had earned it fairly and that it would be worth all it cost. Mother had worked hard all her life and I felt that she had earned it fairly too, but it took a deal of persuading to get her to see it that way. She had finally consented however and to this day she won’t admit that she is sorry, even if she did have some experiences that were not exactly gentle. In the worst of our storms and buffetings, when she knew that the danger was greatest, not one word of fright or complaint did she utter. Even during the big storm on the Gulf, when she had to stay in the cabin most of the night, and listen to the seas smashing over the boat, she was calm and brave and her implicit trust in me stiffened me up when I was good and frightened down inside. She did not get sea-sick once and although our boat was too small for real comfort, she enjoyed the good things and forgot the bad, like a true philosopher.

The third day of May 1909 found us tied to the dock just west of the Wells Street bridge taking on supplies and baggage. It was the day of the start and late in the afternoon. I paused a moment in the mad rush of final preparation. What was this thing that was happening to me? Was I dreaming? In front of me was the river, silent, powerful. Troubled a moment by the wash of a passing tug, it was quiet again and it flowed steadily past me on its long journey to the sea. To the sea! Ah! Seventeen hundred miles to the south! And I was about to join it on that journey. No, I was not dreaming. It was all true. What had been the dream of the years was actually taking place. It seemed impossible, wild, but it was not. Here was the boat at my feet; here was a bag of potatoes waiting to be stowed on board; here was a bushel of walnuts, here a can of olive oil; there in the cockpit were piled boxes of dates and prunes, pails of butter and eggs, packages of wheat, flour, nuts, and supplies without end; there on deck was a coil of new one-inch anchor line thirty-five fathoms long and a new twelve-foot ash pike pole. No it was all real all right. Below in the cabin I could hear Mother moving about trying to bring order out of chaos as was her habit, and down the steps from the bridge came Fred, the crew, with a bag of onions on his back. The last of the “left to the last minute, sure to be forgotten things” had been remembered. All was ready for the start. All the details of the business left behind had been attended to. All the equipment for a six-months cruise was aboard. There were a hundred and thirty gallons of gasoline in the tanks, an amount sufficient for five hundred miles at the least.

Friends had come to say goodbye and had gone back about their business. I looked up at the clock in the Northwestern tower. It was five minutes after six. It was late for a start, but start I must if it was only to run one mile, so I threw aboard the last of the luggage, called Fred to cast off bow and stern lines, threw in the switch, primed and started the engine, then taking the wheel, I threw in the reverse and, with the helm hard to starboard, slowly backed out into the river, swung to the setting sun, and, passing the fire boat Illinois close to port, turned down the south branch and was off.

You must be logged in to post a comment.