Junkyards and Tollbridges

by Steven K. Roberts

Reston, Virginia

13,962 miles

October 2, 1987

Yes, we’re still alive. Through the frenzy of the last three weeks, I have opened a half-dozen mini-files, each an aborted attempt at writing this update. Since the Easton story I have lived a year’s worth of adventure and change, with the notion of “catching up” now as futile as it is flawed. I am a victim of the travel writer’s curse: detailed textures, wonderful and irreproducible, are daily obscured like old paintings back in the epoch of expensive canvas. There’s only so much short-term memory in this aging brain…

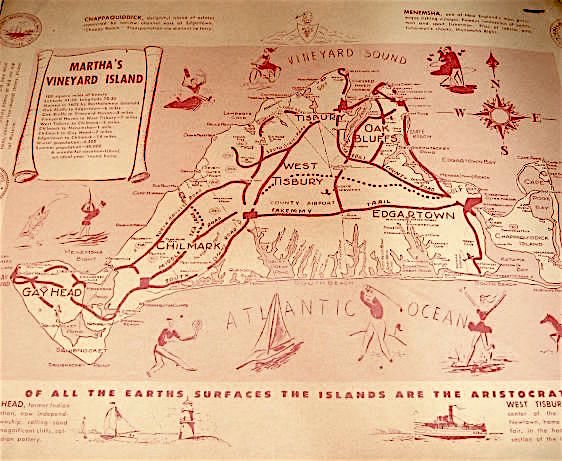

I’m sitting in Wood’s Hole, Massachusetts, waiting for the ferry to Martha’s Vineyard. To my right on this old wooden bench, a giddy couple sings Simon & Garfunkel songs a cappella; to my left, an old woman with brittle straw hair exudes a perfume funk so potent that I can taste the stuff on my tongue. This is quite out of context with the rest of the journey: our bikes are tarped over for a week, packless, somewhere in the suburbs of DC. And as if all this were not alien enough, I’m engaged this week in the attempt to settle a problem with a piece of real estate — for some fellow has seen fit to build a junkyard on top of what was to be my ultimate economic fallback position. Thinking ahead, you see, my mother bought a parcel of Vineyard land back in 1934… for $45. Though my property taxes are now about four times that every year, the idyllic retreat in the woods seems to be buried under old cars. The good news is that nothing lasts forever and land around here is expensive; the bad is that there’s not a huge market for land with a 360-degree junkyard view, even if it IS on Mahtha’s Vin-yahd. So now I’m on a working vacation from a life of frenzy, a mini-sabbatical of real-estate sleuthing in the middle of writing deadlines. “Just up here checking on my property,” I mumble, trying to sound wealthy but wincing at the reality.

No, the real madness of this phase is connected with Washington, DC — with new clients, new radio equipment, new friends, terrifying traffic, the worst roads I have ever had the misfortune of pedaling, and the usual succession of unpredictable events ranging from network magic to friendly millionaires. But first things first.

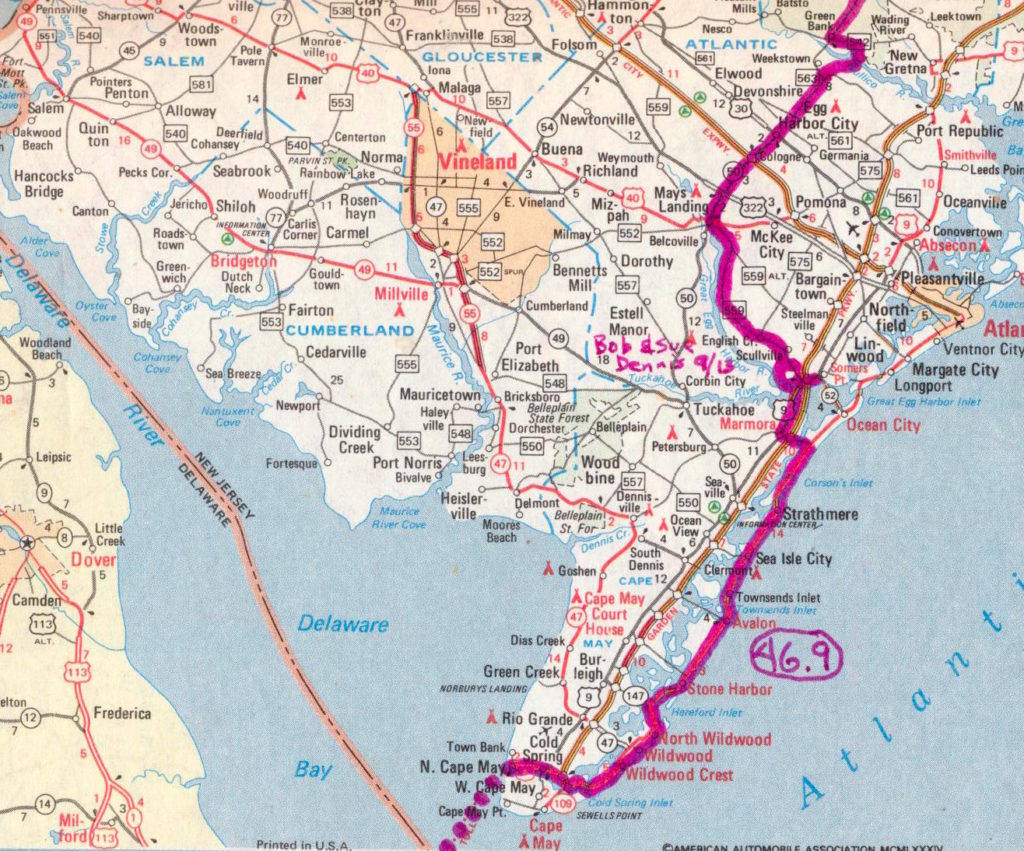

“Forty cents each,” said the uniformed toll collector, trying not to be too obvious about gawking at my bike. He leaned from his booth high atop the Great Egg Harbor Bay bridge and extended a weathered palm.

“But that’s the same as for cars!”

“Same for everybody.”

“You mean, if she and I were riding with four other people in a 6,000-pound Cadillac, we’d pay forty cents, but if we were pedaling a coupla 22-pound racing bicycles we’d pay twice as much?”

“I don’t make the rules. Hurry up, there’s people behind ya.”

With a grumble, I handed over my money, realizing that five such bridges would have to be crossed en route down the South Jersey shore. The purpose of the toll was unclear: the roads were cracked and rutted, the shoulders a ragged disaster of glass and potholes, the off-season culture torpid and senile. Four dollars admission for this — plus twelve more for the ferry that would carry us at last out of the mess and into placid Delaware?

As the Strathmere bridge approached, I called Maggie on the radio. “Pull up beside me and take my right hand. Our bikes just became an 8-wheeled human-powered vehicle.” Smoothly, we blended into a single 890-pound assemblage of faded ripstop and non-sequitur technology, 304 spokes flashing under a pair of sweat-glistened pilots linked fleshwise. Startled, the toll-taker took our tokens and watched us roll away. It’s a two-for-one special!

Townsends Inlet was a piece of cake, the old guy smiling and wishing us good day as he took our forty cents. But then came Hereford, the link between Stone Harbor and Wildwood.

“HEY!” cried the uniformed representative of New Jersey. “That’s forty cents each!”

“We’re one!” I cried as we rolled away, watching in the mirror as he ran a few ineffectual steps in our direction and shouted to his co-workers. Accelerating down the hill, I exulted in having pulled the Great Tollbridge Caper until it suddenly struck me that we could easily be outrun by motorized cops.

Into the mess of Wildwood we went, paranoid, thinking of police harassment, fines, and jail. In my head, I wrote the newspaper story: “High-tech nomads defraud Jersey Toll Authority,” complete with an interview in which I held forth on the subject of cyclists’ rights and deftly demonstrated the absurdity of their laws. But few in this crotchety community would rally to our aid… we’d languish in some Wildwood holding pen until the humiliating court appearance…

Through all this, I zigzagged down back streets and alleys, acutely conscious of being the most visually distinctive thing in this town of plastic palms and carbon-copy motels. The Winnebiko, I’m afraid, ain’t much of a getaway car:

“What was the suspect driving?”

“Wellsir, it was like nothing I’ve ever seen — he was on this giant blue computerized lawn chair with one o’ them highway flashers on the back, pullin’ a bright yellow trailer with orange flags on it. He was goin’ about ten miles an hour… down that way…”

I sprinted behind food marts and ignored tubby poolside interrogators, crept through intersections and probed every side street for police cruisers. “Clear,” I would whisper to Maggie electronically, compounding my sins by using ham radio to facilitate The Escape. When we arrived at the next tollbridge, we found traffic stopped and the span raised… thoroughly convinced that this was a roadblock in our honor.

Ah, paranoia. I haven’t felt that way since, oh, somewhere back in the early 70’s when everybody who was cool was also guilty. Sort of nostalgic, now that I think about it… but by the time we were safely on the ferry and cruising Delaware waters, I was chuckling inwardly at my fantasies and looking ahead to a new life, free from government persecution in America’s first state (and my 26th).

Lewes, Delaware. The differences were immediately obvious — this town was quiet, historic, and low-key about its tourist trade. “First town, first state,” strangers on the street would say, taking the time to point out significant gravestones in the cemetery and tell stories of the shipwreck that helped populate it. There’s always a distinctive flavor to a place that recognizes and preserves its own past (along with an ever-present danger of ignoring the future).

Except for the open rainy expanses of the Pine Barrens, New Jersey had been difficult on all levels. Traffic, of course, was everywhere insane — the overpopulation of the East very much in evidence. In Pendleton, a rough Army Base border town, I came upon a fight between drivers: women screaming, cops sprinting onto the scene with billy clubs at the ready, macho jerks shouting curses and brandishing tattooed fists.

Pressing on into the periphery of the Philly-Trenton megalopolis, we witnessed a sort of mega-suburbia, with everybody nice, so terribly nice — but constantly in a rush. I think of all that general affluence and puzzle over isolation from the land, wasteful lawn sprinklers in the rain, and the complex layers of appropriateness that mask deep undercurrents of resentment and repressed anger. It’s not an uncommon syndrome, but it seems more widespread near big cities… especially eastern ones where crowding is a reality and real-estate economics force epic commuting marathons.

While in that area, we visited Medford — home of my mini-publisher, Learned Information. (At last, on the eve of Computing Across America publication, we have a written contract; and yes, the book is really about to come out after all these years of frustration, New York publishing giants, and unkept promises.)

But such things seem vague, almost a fiction. The road, while an endless source of experience, obscures its own past. New Jersey is as abstract as Ohio, for we’ve since floated the Delaware Bay and pedaled the gentle Delmarva, portaged the Chesapeake Bay Bridge with GEnie friend Russ Patterson and tangled with DC traffic. We spent a delightful evening in the residual literary vapors of the Sophie Kerr house — a B&B in Denton, Maryland. We’ve dealt with noisy infestations of children, relaxed in the home of a friendly millionaire, eaten blue rock crab, and bounced along the worst city streets I’ve ever felt.

Yes, it’s been a busy time. I’ve interviewed with National Geographic and done a bike demo at their building, grinned through a cover-story photo session with USA Today, met a passel of congressmen, set up a Voice of America interview, displayed the bike at the Smithsonian, acquired a new online-searching client, bent an unbendable 48-spoke undished wheel on brutal DC streets, probed the limits of the packet universe with simultaneous connects from my bike to all corners of the US, designed an enclosure for my new HF ham radio station, edited 50 chapters of CAA page proofs, visited old friends, and written a new version of bicycle control system software that chats via touch-tone remote control with passers-by. Meanwhile, two magazines and three clients are all on my case for being late with projects… while I sit here smelling Eau Contraire perfume and waiting for a ferry to Martha’s Vineyard.

Ah, the lazy life of a nomad… when somebody on the street says “gee, must be nice to just take it easy and travel all the time…” I have a small red flash of quiet rage.

The International Human-Powered Vehicle Association championships that attracted us to DC in the first place have come and gone, making a quiet ripple in the local media. There’s an art to PR in the Big City — in this time of no football, these eccentric and visually-intriguing human-powered events could have occupied whole pages of the Post and even a few moments on the six o’clock superficialities. But the competitions took place without fanfare on the Smithsonian Mall, in Anacostia Park, at the University of Maryland — scattered so widely over this megalopolis that they seemed lost in the noise. Despite the delightful creativity and brilliance of the participants, this seemed a gathering of a subculture, a reminder of academia. But, the IHPVA does not belong on the fringe… which is where it might appear to those who aren’t directly involved.

(In this time of quiet transportation crisis, as we pay an overpriced Navy to protect our interests in the Persian Gulf so we can continue to squander petroleum, it makes sense to consider alternatives. But the public, for the most part, is bored with the energy issue, ignorant about solar power, addicted to yupmobiles, too lazy to pedal to work, and too proud to carpool or rub elbows with the riffraff on public transportation. As such, we zoom headlong into a really major crisis, while groups like the IHPVA earnestly present intelligently scaled and well-researched alternatives to many of our transportation needs — fighting an uphill battle trying to get heard. <sigh> It’s an old story.)

To participate in the IHPVA events, we had to ride into town from the Maryland suburbs. Thinking to simplify this, I borrowed an impressive-looking DC bicycle map — delighted to find a network of bike routes.

But after about 150 miles of wandering this mad place, I can say without hesitation that DC is the most difficult riding of my 14,000 miles on the road. There are a lot of bicycle activists here, pushing vocally for commute paths and other improved routes, but the reality has fallen far short of the ideal. The roads are brutal, ragged, wheel-eating things; the paths, where they occur, seem designed only for mountain bikes (except for the smooth and relaxing W&OD path, once a railroad line, running from DC to Leesburg). Three times, we were dead-ended by a bike route that looked fine on the map but led only to an obstacle — a rutted gravel hill, a set of steps, a too-narrow bridge. Even a cross-town ride of only fifteen miles left us with clenched teeth and grimaces hardened by a moment-to-moment struggle for survival.

Culturally, DC was not at all what we expected. It has a reputation as a racial war zone, a place of danger and terror outside the sanitized, tourist-oriented microworld of capital attractions. Nervously, we penetrated neighborhoods that make most white middle-class tourists lock their doors and accelerate through yellow lights, avoiding eye contact with the residents as we rushed to our destination.

But the black neighborhoods were far more friendly than the economically equivalent white ones, with no shortage of smiles, thumbs-up, grins, and encouraging shouts. After I relaxed, I found myself stopping to chat and hand out flyers, intrigued by the cultural differences between children. The black kids, wide-eyed and excited, abandon their play and run toward us yelling: “Take me a ride! Take me a ride!” The white kids either stand gaping, laugh derisively, or ask the absurd question, “how much did that cost?”

But all that notwithstanding, the streets were garbage: violent bike-rattling surfaces glittering with glass and buckled by decades of freeze-thaw cycles. Repair of roads is not high on the priority list of DC government… and you know where that leaves the bike paths: dead last.

En route to visit our wealthy friend in the wooded neighborhoods north of Silver Spring, for example, we found the Northwest Branch bike path. For 3 or 4 miles we rode along a creek, sniffing occasional sewage but otherwise grateful for the relief. Then it ended.

Now, according to the DC bicycle map (an oversized confusing document printed on paper that falls apart upon being handled for a day), the route was to connect with a subdivision street just inside the Beltway. It did, in a sense — via a half-mile of steep, deeply-rutted gravel drive, passable only to jeeps, hikers, and mountain bikes. Grumbling, we turned back two miles and took the previous exit, which dumped us into the middle of a major intersection between 4-lane highways, complete with square curbs and more glass than we had seen yet. Plodding along in the rain on a narrow walk between a concrete wall and the roar of traffic, I got a flat tire — which I fixed in the parking lot of a housing project while watched by sullen, suspicious teenagers for whom English was a second language. This was a dramatic prelude to three comfortable days of deep affluence in a wooded neighborhood of movers and shakers, a place where the dog cost more than my first car.

After all this, the thought of pedaling Out West seems a fantasy. Are there really quiet, smooth roads and beautiful views somewhere, places vast and humbling, silent and calming, far from the tangle of angry traffic?

And… is there really dollar-a-night camping on the west coast? I’m sitting now in the tent (it’s raining, naturally), in the Martha’s Vineyard Family Campground. For five of us, the bill was $40. To camp for one night! (Plus 25 cents per shower, a misguided attempt at conservation that succeeds only in making people take much longer showers than they normally would, trying to get their money’s worth.)

The real-estate issue is an entertaining one. For the last two days we have been prowling the island, asking questions, talking with attorneys and bureaucrats and concerned neighbors, gradually piecing together the history of my property and the legal options that lie ahead. (Hey — any auto buffs out there wanna by a third of an acre of prime wheel estate?)

Life on the Vineyard has been colorful, to say the least. (“It’s a nice place to live, but I wouldn’t want to visit there,” says Jim Mitchell, my Lake City friend who jeeped in from Colorado and drove us to Massachusetts for the pleasure of dabbling in an oddball land deal.) This overpriced campground, for example, charges $2 for daytime visitors, requiring that campers check with the office before inviting them. Rough calculations show that their 180 sites generate nearly a quarter of a million dollars in gross receipts per year. Hmmm… maybe I could open a junkyard campground…

Other Vineyard vignettes: There are toilet police on the waterfront to guard against unauthorized face-washing (and you’re supposed to tip them). The Hole-in-One donut shop gives free coffee if you can sink your first putt across their floor (be careful — it breaks hard to the left). The “On Time” ferry to Chappaquiddick is always on time, since there’s no schedule. Huge queues of blue-headed gawkers stroll Edgartown, shuffling through shops and inquiring about the Kennedys. And, of course, there’s the junkyard situation which, in any other context, would be hilarious.

Ach, it’s madness all of it. I’m back in the DC area now, renewing a 20-year friendship of techwizardry and shared madness with Steve Orr and family — and already the Vineyard seems abstract and confusing. You must realize by now, of course, that this bicycle odyssey is but the eccentric manifestation of my timeline through life, a sort of consistent promenade like the theme that unifies Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. At every stop, there’s a new crisis, a new adventure, a new friend, a new terror. Few of those have anything to do with cycling, but still I’m “Computing Across America,” pedaling furiously when not hunkered down over a keyboard trying to put out the fires of this intrinsically unstable but wildly entertaining business.

Next? By the time this is online, I’ll be in Rockville, wandering the halls of GEnie, worrying about the onset of winter while meeting the folks who keep the network alive. See you somewhere….

You must be logged in to post a comment.