Paper Databases

This is quaint now, 30 years later, discussing areas in which paper is still better than a computer… yet it still has a grain of truth even though “hypertext is a step in the right direction.”

by Steven K. Roberts

Computer Currents

October 5, 1987

written in Reston, VA

This is typical.

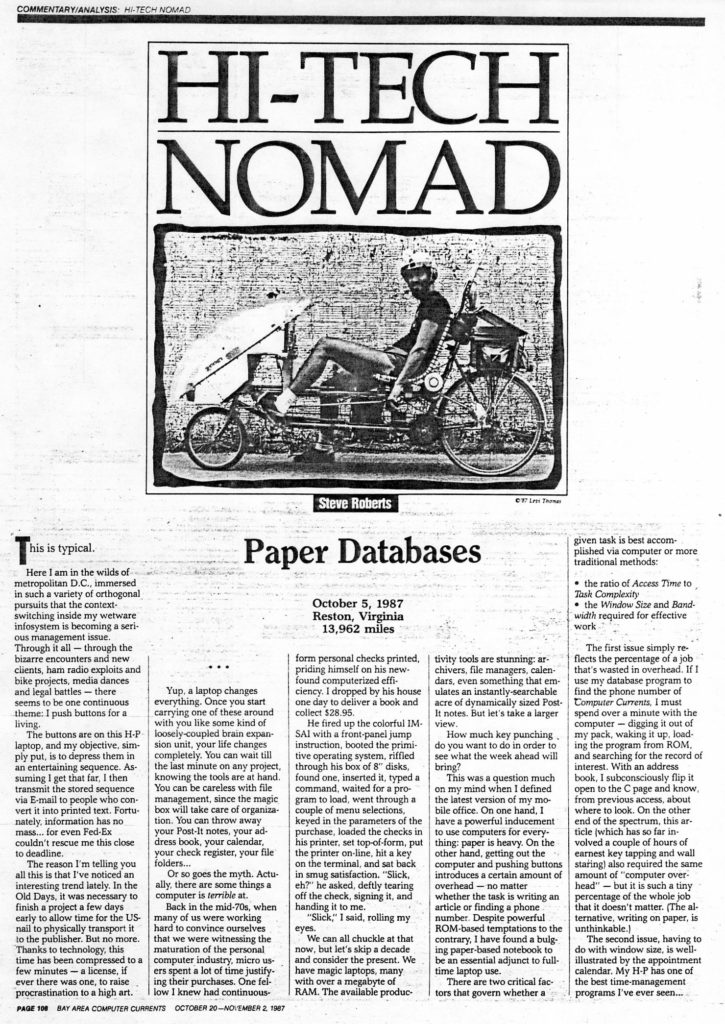

Here I am in the wilds of metropolitan D.C., immersed in such a variety of orthogonal pursuits that the context-switching inside my wetware infosystem is becoming a serious management issue. Through it all — through the bizarre encounters and new clients, ham radio exploits and bike projects, media dances and legal battles — there seems to be one continuous theme: I push buttons for a living.

The buttons are on this H-P laptop, and my objective, simply put, is to depress them in an entertaining sequence. Assuming I get that far, I then transmit the stored sequence via E-mail to people who convert it into printed text. Fortunately, information has no mass… for even Fed-Ex couldn’t rescue me this close to deadline.

The reason I’m telling you all this is that I’ve noticed an interesting trend lately. In the Old Days, it was necessary to finish a project a few days early to allow time for the USnail to physically transport it to the publisher. But no more. Thanks to technology, this time has been compressed to a few minutes — a license, if ever there was one, to raise procrastination to a high art.

Yup, a laptop changes everything. Once you start carrying one of these around with you like some kind of loosely-coupled brain expansion unit, your life changes completely. You can wait till the last minute on any project, knowing the tools are at hand. You can be careless with file management, since the magic box will take care of organization. You can throw away your Post-It notes, your address book, your calendar, your check register, your file folders…

Or so goes the myth. Actually, there are some things a computer is terrible at.

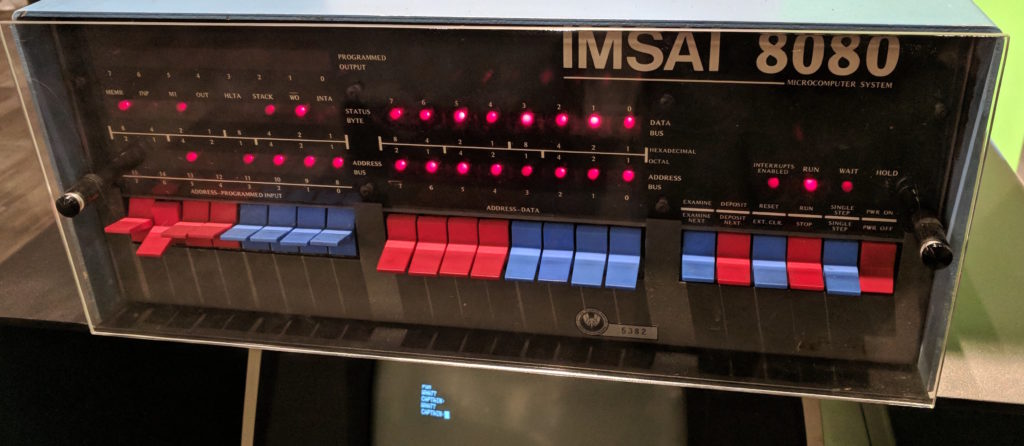

Back in the mid-70s, when many of us were working hard to convince ourselves that we were witnessing the maturation of the personal computer industry, micro users spent a lot of time justifying their purchases. One fellow I knew had continuous-form personal checks printed, priding himself on his new found computerized efficiency. I dropped by his house one day to deliver a book and collect $28.95.

He fired up the colorful IMSAI with a front-panel jump instruction, booted the primitive operating system, riffled through his box of 8″ disks, found one, inserted it, typed a command, waited for a program to load, went through a couple of menu selections, keyed in the parameters of the purchase, loaded the checks in his printer, set top-of-form, put the printer on-line, hit a key on the terminal, and sat back in smug satisfaction. “Slick, eh?” he asked, deftly tearing off the check, signing it, and handing it to me.

“Slick,” I said, rolling my eyes.

We can all chuckle at that now, but let’s skip a decade and consider the present. We have magic laptops, many with over a megabyte of RAM. The available productivity tools are stunning: archivers, file managers, calendars, even something that emulates an instantly-searchable acre of dynamically sized Post-It notes. But let’s take a larger view.

How much key punching do you want to do in order to see what the week ahead will bring?

This was a question much on my mind when I defined the latest version of my mobile office. On one hand, I have a powerful inducement to use computers for everything: paper is heavy. On the other hand, getting out the computer and pushing buttons introduces a certain amount of overhead — no matter whether the task is writing an article or finding a phone number. Despite powerful ROM-based temptations to the contrary, I have found a bulging paper-based notebook to be an essential adjunct to full-time laptop use.

There are two critical factors that govern whether a given task is best accomplished via computer or more traditional methods:

- the ratio of Access Time to Task Complexity

- the Window Size and Bandwidth required for effective work

The first issue simply reflects the percentage of a job that’s wasted in overhead. If I use my database program to find the phone number of Computer Currents, I must spend over a minute with the computer — digging it out of my pack, waking it up, loading the program from ROM, and searching for the record of interest. With an address book, I subconsciously flip it open to the C page and know, from previous access, about where to look. On the other end of the spectrum, this article (which has so far involved a couple of hours of earnest keytapping and wall staring) also required the same amount of “computer overhead” — but it is such a tiny percentage of the whole job that it doesn’t matter. (The alternative, writing on paper, is unthinkable.)

The second issue, having to do with window size, is well-illustrated by the appointment calendar. My H-P has one of the best time-management programs I’ve ever seen — with the ability to carry a prioritized task list forward, leave completed items where they were shot down, archive appointment and To Do files, and even create searchable free-text notes that remain associated with the days of their origin. Neat stuff. But what deadlines and commitments do I have coming up in the next two weeks? The only way to find out is to page through the days, one at a time, looking at each one out of context with its neighbors.

Compare this to a regular calendar. You see a week or more at a glance, recognize notes made in that red pen you used when at so-and-so’s office, and discern the difference between items marked off, crossed out, checked, superseded, and connected by arrows to others. You can even read things that have been erased, and glance into the short-term future to get a general sense of how horrible it’s going to be. “Oh no, next week’s a disaster. How about the following Monday?”

The thing that makes this work is bandwidth — for the amount of information that can be funneled through existing display technology is minimal compared with that on a page of notes. (I know, I know — hypertext is a step in the right direction.) Until computers support all the subtle flexibility of a blank page along with their natural repertoire of information handling skills, there will be a few things that work better the old way.

Just which things these are depends on who you are and what you do, but a quick look at my own system may prove useful.

At the heart of my portable office, of course, is the laptop — about which I have already written in some rhapsodic detail earlier in this series. It’s nestled in foam, supported by an external floppy drive in my trailer and a stack of 3.5″ disks… and I can’t imagine life without it.

But I also carry a small, three ring, six by nine inch binder with a calendar book stuck to the front with velcro. Every project, close friend, client, state, sponsor, bike subsystem, or topic of interest has its own page — organized alphabetically and thumb-indexed. I can find the status of anything that matters faster than I can type DIR and check for free space, with the flavor of the notes conveying information that would require a lot of extra words on the screen. The binder is heavily cross-referenced, with some pages pointing to manila folders, others linked to microfiche files, and still others referring me to .ARC files on disk. Here, taking advantage of the full information bandwidth of my visual system, is a non-volatile meta-index to the gigabytes of text and graphics that roll around the country with me.

I couldn’t live without it, either. A few years will pass, maybe decades, before laptops can fully replace paper… but logarithmic extrapolation insures that it will happen. In the meantime, don’t handicap yourself by insisting on complete computerization. We are now in the era of hybrid systems and strip-tease technology, and are just starting to glimpse the possibilities…

Cheers from the Capitol!

You must be logged in to post a comment.