Life Aboard the Winnebiko – Bicycle USA

This was a fun article, though I have to wince a little at the tale on the first page in which I recounted the Great Tollbridge Caper. I actually thought this was pretty funny, but the Bicycle Advocate of the NJ Dept of Transportation wrote to the magazine to denounce my temerity in boasting about my idiotic behavior, indicating that I may have jeopardized the precarious rights of cyclists to use the bridges along the Jersey shore. Oops.

I apologized, of course, still with a bit of a chuckle… it was hard to take this too seriously, though I do sincerely hope that no rollbacks of cyclists’ rights occurred as a result of our playful antics that afternoon. It’s an ongoing battle for equality, I know. I respect those who have spent time in the trenches, and regret any negative impact that might have occurred.

Anyway, this piece was written on the road, during the delightful east-coast leg of my travels with Maggie, just before the Computing Across America book was finally published and we bought a school bus to wander the US for a year before settling in to start the BEHEMOTH project…

by Steven K. Roberts

Bicycle USA

May, 1988

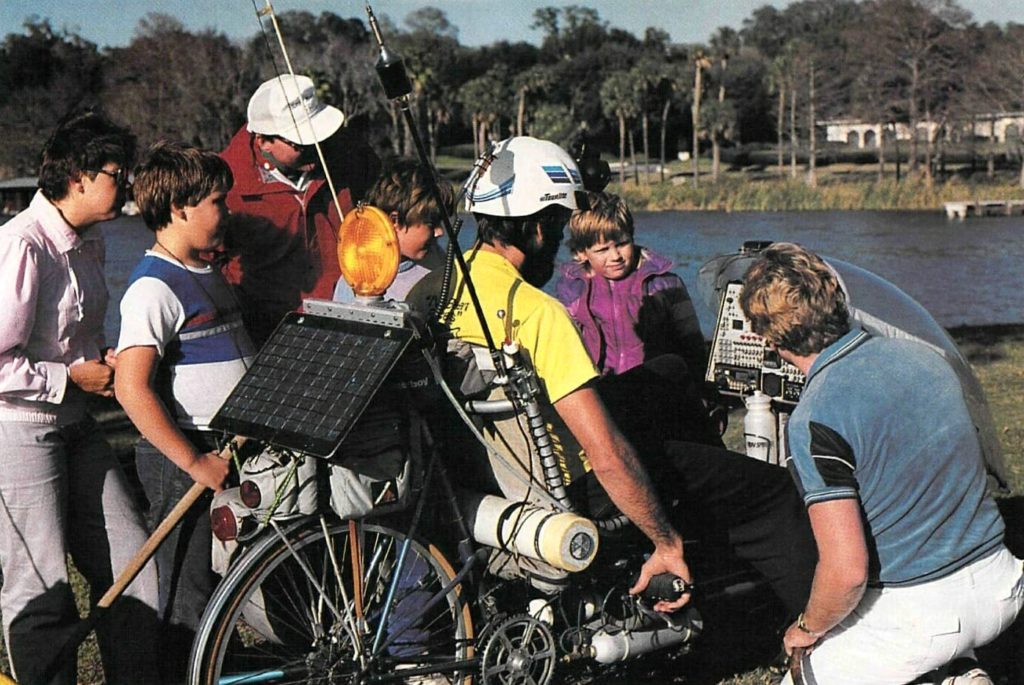

When you live full time on a 12-foot-long, 275-pound, 54-speed recumbent bicycle with two solar panels, a trailer, a ham station, and five computers, you get used to strange reactions from people on the street. I’ve been mistaken for an airplane, an alien, a theatrical prop, and a piece of highway maintenance equipment. I’ve been taken home, gawked at, laughed at, spat at, seduced, and photographed. Speculations about the Winnebiko have ranged from medical equipment to weather research, and many people ignore the pedals and insist that there has to be a motor hidden somewhere. I’ve spawned all sorts of bizarre theories, like the conclusion that I made the front wheel small so I’d always be going downhill.

Strange bicycles tend to encounter strange obstacles, as well as a constant barrage of maddening and occasionally thought-provoking comments (“Um, does all that tell you why you’re doing this?”). A full-time tour can be challenging to anyone, of course, but traveling around on a high- tech megacycle laden with an eighth of a ton of gizmology presents a whole new set of problems to overcome.

So why do I do it? What kind of mad dream has driven this journey past the four-year mark?

I’ve been living on the road since 1983, and every now and then the obstacles and irritants of travel seem overwhelming, but one thing always resurfaces: a slowly evolving version of the same passionate obsession that drove me to trash my “successful” midwest suburban lifestyle and hit the highway. Still, there are times . . .

“Forty cents each,” said the uniformed toll collector, trying not to be too obvious about gawking. He leaned from his booth high atop the Great Egg Harbor Bay Bridge and extended a weathered palm.

“But that’s the same as for cars!”

“Same for everybody.”

“You mean, if she and I were riding in a 6,000-pound Cadillac, we’d pay a grand total of 40 cents, but if we were pedaling 22-pound racing bicycles we’d pay twice as much?”

“I don’t make the rules. Hurry up, there’s people behind ya.”

With a grumble, I handed over my money, realizing that five such bridges would have to be crossed en route down the South Jersey shore. The purpose of the toll was unclear: the roads were cracked and rutted, the shoulders a ragged disaster of glass and potholes, the off-season culture torpid and senile. A four-dollar cover charge for teeth-clenching headset bottom-bearing abuse — plus twelve more for the ferry that would carry us at last out of the mess and into placid Delaware? No way.

As the Strathmere Bridge approached, I called Maggie on the two-meter ham radio. “Pull up beside me and take my right hand. Our bikes just became a four-wheeled human-powered vehicle.” Smoothly, we blended into a single 825-pound assemblage of faded ripstop and non-sequitur technology, 304 spokes flashing under a pair of sweat-glistened pilots linked fleshwise. Startled, the toll-taker took our tokens and watched us roll away. It’s a two-for-one special!

Townsends Inlet was a piece of cake, the old guy smiling and wishing us good day as he took our coins, but then came Hereford, the link between Stone Harbor and Wildwood. “Hey!” cried the uniformed representative of New Jersey. “That’s 40 cents each!”

“We’re one!” I cried as we rolled away, watching in the mirror as he ran a few ineffectual steps in our direction and shouted to his co-workers. Accelerating down the hill, I exulted in having pulled the Great Tollbridge Caper until it suddenly struck me that we could easily be outrun by motorized Jersey cops.

So into the mess of Wildwood we went, paranoid, thinking of police harassment, fines, and jail. In my head, I wrote the newspaper story: “High-tech nomads defraud Jersey Toll Authority,” complete with a jailhouse interview in which I held forth on the subject of cyclists’ rights, but few in this crotchety community would rally to our aid. We’d languish in some Wildwood holding pen until the humiliating court appearance.

Through all this, I zigzagged down back streets and alleys, acutely conscious of being the most visually distinctive thing in this squalid town of plastic palms and carbon-copy motels. The Winnebiko, I’m afraid, ain’t much of a getaway vehicle:

“What was the suspect driving?”

“Wellsir, it was like nothing I’ve ever seen — he was on this giant blue computerized lawn chair with one o’ them highway flashers on the back, pullin’ a bright yellow trailer with orange flags and a safety triangle on it. He was goin’ about 10 miles an hour… down that way…”

I sprinted behind food marts, ignoring tubby poolside interrogators, crept through intersections, and probed side streets for police cruisers. “Clear,” I would whisper to Maggie electronically, compounding my sins by using a ham radio to facilitate The Escape. When we arrived at the next tollbridge, we found traffic stopped and the span raised and were thoroughly convinced that this was a roadblock in our honor.

Ah, paranoia. I haven’t felt that way since, oh, somewhere back in the early seventies when cops were pigs and everybody who was cool was also guilty. Sort of nostalgic, now that I think about it, but by the time we were safely on the ferry and cruising Delaware waters, I was chuckling inwardly at my fantasies and looking ahead to a new life, free from government persecution, in America’s first state (and my 26th).

Well, there’s always something: Brutal wheel-eating roads and Washington, D.C., bike routes that dead-end in a set of steps. Glass shards from a subculture that respects the sound of breaking bottles. Motel doors an inch too narrow for Equinox trailers. Hosts who live on the third floor of an apartment building in a high-crime area, necessitating a major back-wrenching project for an overnighter. Kids who jeer at things they don’t understand. Cops who pull us over to see what the hail is threatenin’ their citizens (I was even interrogated for uploading an article to the GEnie network through a pay phone in Whiteville, N.C.).

Those are just moments. You have to expect a few problems when you flaut convention, ignore tradition, deny ultralight cycling style, and build a touring system designed to support a full-time free-lance writing business on the road. The good news is that the problems are trivial when compared to the pleasures: adventure, change, lifestyle sampling, health, new friends, and the pure visceral sensations of silent backroad cruising.

Perhaps the deepest pleasure in our case is the fact that home has become exquisitely portable: Maggie and I maintain no suburban fall-back position to comfort us when the road bites back. As such, “home” has become a complex three-part phenomenon consisting of America itself, the computer networks that keep us in contact with a world-wide electronic community, and, of course, the eccentric “rolling stock” that opens doors everywhere we go. After 15,000 miles, all three have become so familiar and comfortable that we never really feel disconnected from normalcy. Honest.

Closely connected to the issue of home is the business side of the Computing Across America Traveling Circuits. I write for a living, plying my key-tapping trade from beaches, backyards, hostels, motel rooms, campgrounds, and even the bike itself. There is enough information-processing and storage capacity on board to handle the entire operation, and all communication with my offices and publishers takes place through the GEnie network. The result? It never matters where we are.

This, in the context of an open-ended bicycle tour, is profoundly liberating. Occasionally we meet others on the road, pedaling furiously to reach a distant objective, acutely conscious of time, money, and miles. Circumstance has forced them to become obsessed with where they’re going, making it impossible to fully appreciate where they are no matter how pure the original motives.

Of course, those motives can differ widely. Not so long ago, we visited the RAAM racing team of Jim and Kathie Mulligan and found ourselves staring at each other in mutual awe like friendly aliens. He rides more miles in a day than I do in a week, and my bike is about ten times the weight of his. But we were drawn together nevertheless by the love of cycling.

Freedom to travel full-time is only the beginning. Without technology, this whole adventure would quickly fall apart. Before hitting the road in relative domesticity with Maggie, I did a solo 10,000-mile odyssey on a primitive version of the Winnebiko. A significant realization struck me in West Texas: Every ten thousand miles is a thousand pedaling hours, and as a struggling hand-to-mouth freelancer I could no longer afford to waste them. And so, a year later, I built a binary keyboard into the handlebars

and a word processing system into the console. Now, while pedaling along a quiet country road, I can write a magazine article (or play a video game). The system allows me to capture ideas that once drifted away in the breeze like the smells of camp cooking, leaving only a vague memory of the insights that had spawned them.

(Oh, for you techies out there, my Grand Turing Machine consists of five processors: a 1.2 Megabyte HP Portable PLUS; a heavily modified Radio Shack Model 100 built into the console with a half-meg of RAM and extensive ROM software; a custom 68HC11 “bicycle control processor” that takes care of the handlebar keys, security system, and real-time functions; a Votrax synthesizer for text-to-speech; and a Z-80-based Pac-Comm TNC for electronic mail from the bike. They all run on battery-backed-up solar power and are tied together by a high-speed serial crossbar network.)

There’s more. The bike’s networking capacity and my perennial obsession with communication keep manifesting themselves in new forms. First, I now carry a full solar-powered ham radio station (in addition to the absolutely essential two-meter FM rig for bike-to-bike chatting and local repeater access) that allows me to make international contacts from a campground or host’s backyard. Recent connections have included Germany and the Canary Islands — not to mention a variety of stateside hams who have joined my extensive “hospitality database” of over 2,500 places to stay. Second, the merger of radio magic with digital technology has generated an active subculture called packet radio that adds a whole new dimension to this adventure. Now I can not only send global electronic mail while pedaling, but also tell the bike to transmit a periodic beacon that invites packet users to sign on and leave messages in my rolling mailbox. On and on we go, adding new systems as they become available. It is tempting to view the whole affair as a sort of technological tour de force, a loony extrapolation of a life obsessed with the magic of silicon and the lure of the unknown. But there’s another level to all this — one that translates neatly into the lives, the tours, the dreams of other travelers.

It occurs to me almost daily — whenever I see the longing, the envy, the far-away look. I see it in the eyes of business people at lunch, kids on the street, fellow cyclists, and L.A.W. members who take us in for a night and sit in delighted conversation around the loony excursion module poised like a spaceship in their living room. It is the look of dreams unfulfilled, of the deep ache to taste freedom.

Not everyone wants to do exactly what we’re doing, of course: it’s sweaty, difficult, complex, slow, occasionally dangerous, and often frustrating. But there are other dreams, countless wild excursions of the human spirit ranging from mountain-biking Kilimanjaro to owning a boutique, from winning a Scrabble tournament to publishing a novel, from bench-pressing a Yamaha to juggling three running chain saws. Whatever. There are at least as many possibilities as there are people to dream them. The problem is that few dreams survive infancy. Most people deny their dreams and passions, having been convinced by parents, teachers, and bosses over the years that their energies should be focused on work. Often such advice is offered “for your own good,” since there really are a lot of things to fear Out There. Hell, you might even get robbed, run over, or hassled by customs. Growth of any kind takes courage — not only the obvious courage to risk the various Unknowns, but (more subtly) the courage to keep on stubbornly nurturing your crazy dream when everybody you know insists that it’s stupid, pointless, grandiose, or a waste of time.

Well, my point is simply this: the greatest risk of all is taking no risk. Your dreams are infinitely more interesting than your responsibilities, and nobody will ever make them come true unless you do. If there’s an ultimate tour that would combine all your passions, express all your ideas, and turn you loose to seek your destiny, then by all means, go for it! The toll booths and customs officers of the world are but a source of road stories, fodder for your next round of fireside tales with new friends.

I’ll see you on the road, somewhere out there.

You must be logged in to post a comment.