Micromatics

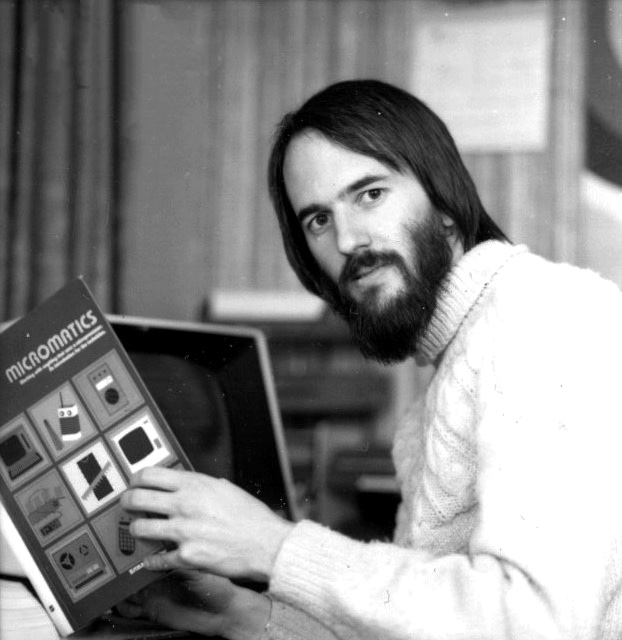

My first book, written for technicians encountering service issues with those newfangled microprocessors, was published in October 1980. This fell out of a series I wrote for Electronic Technician/Dealer magazine beginning with the August 1978 issue, and covered what was then a rather esoteric subject… driven by the recognition of this transformative technology as it rapidly spread through every domain of consumer electronics and industrial control systems. That first article was called “Micros on your bench?” and the opening blurb said: “Mr. Roberts believes it is no longer feasible for the electronic servicing community to consider computers as part of another technological reality.”

As the magazine series unfolded, it became a fairly substantial body of information (for its time), covering everything from design concepts and microprocessor innards to interfacing, programming, and service issues. Somewhere along the way, I connected with Nat Wadsworth of Scelbi in Connecticut… and got my first book contract! Micromatics was born.

This page includes the cover art, marketing literature, and a review that appeared in Microcomputing about a year later. While the book never made the best-seller lists (being aimed more at technicians and industrial applications than the eager personal-computer marketplace) it was a hugely transformative moment in my life… and was soon followed by a Prentice-Hall textbook about industrial control systems. This book included the complete schematics and assembly listings of the industrial data collection terminal I designed for Corning Glass, creating a detailed context for discussion of real-world issues. Every now and then, one appears on Amazon, but they are rare.

Micromatics

by Steven K. Roberts

Scelbi Publications

October, 1980

PUTTING IT ALL TOGETHER

You have been involved with microcomputers a few years…. or perhaps just a few months. You have been having a lot of fun, learning about the hardware, the CPU, memory and interfacing. Then there is the software — the programming, debugging, making the system work — it is a seemingly endless process. There is always something new to learn and do.

And yet, there still seems to be something missing. You can’t seem to put your finger precisely on it, but you have that vague feeling that you haven’t quite tied everything you have learned all together yet. It hasn’t “jelled” to your complete satisfaction. You have a lot of the little pieces assembled in your mind…. Now, if you could just step back and get the whole picture all at once you know that you would be the master of the subject.

You are not alone. Thousands of others have felt exactly the same way.

Finally, somebody did something about it! Who? Steven K. Roberts, that’s who. A young engineer who has spent most of his waking hours the past seven years designing and implementing microprocessor controlled systems. A degree’d engineer who has come up through the ranks, Steve learned the business through experience. He has then done what few do — he took time out to tell others what he has learned.

Steve has a rare talent. He has the ability to communicate clearly and effectively with other people. He has an easy going style that makes technical information read like a “who-dunnit” mystery. It keeps you fascinated, intrigued, eager to read on.

He puts the subject all together for you. He integrates the aspects of hardware, the chips, the peripherals, ties all this in with the software, the programs, machine instructions…. He fits it all together so sensitively and skillfully that you can almost feel your knowledge expanding moment-by-moment, until — BAM — it hits you full force: You realize that you really know and understand the subject matter. This is a special gift to receive, a special joy to be felt. And, one that you certainly owe to yourself!

Order your copy of MICROMATICS today. It is our product No. 81, just $19.95 for a beautiful hardcover volume. Enjoy!

Here is the back-cover copy:

This review appeared in Microcomputing the following year, but is here on this page to keep it all in one place:

Micromatics

by Steven K. Roberts

Scelbi Publications, Hardback, 190 pp

Review by J. C. Hassall, Blacksburg, Virginia

This book was written for the electronics technician who doesn’t need to know (or possibly care) how the various internal timing and control signals relate. It was written for the electronics technician who must use a microprocessor in an integrated system to interface to the outside world. In other words, it picks up where the others leave off—at the outside world.

While the microprocessor is not ignored, it is de-emphasized, and viewed as one component in a system, rather than as an all-important device to which the system is appended.

The author takes an excellent pedagogical approach to the subject matter by relating the reader’s experience, or “internal model of the world,” to the text. While he assumes that the reader is familiar with basic electronic terminology, he also assumes that the reader knows little or nothing about microprocessors.

The author introduces in chapter 2 a computer-controlled stereo cassette deck. By first describing the basic required functions in block diagram form, the author effectively details the system requirements without frustrating the noncomputerist reader with a lot of computer jargon.

Because it would be naive to expect any book on this subject to make an adequate presentation and not establish a basis for the reader’s comprehension of how a computer system operates, chapter 3 gives the reader a first look at the hardware. Buses are explained, along with logic states, memory types and organization, control signals and the like. At the end of the chapter, the previous information is related back to the real-world example of the cassette controller.

Chapter 4 looks at the internal design of the 8080. The 8080 was chosen, as opposed to more advanced chips, because it represents one of the major families of microprocessors, and most of the others are closely related. However, in subsequent chapters the Z-80 is used as a design example. While the transition from 8080 to Z-80 is relatively easy for the experienced reader, the author should have used one chip or the other.

While Roberts does not go into a great deal of detail on the internal design, the chapter provides a good foundation for the software discussion, which begins in chapter 5. The author alludes to machine-language instructions using binary, hexadecimal and decimal numbering systems, and then quickly moves to assembler language programs as the basis for the control network programming to be done throughout the text. Through judicious use of flowcharts and lots of written description, even the uninitiated reader can understand the examples. Only a few representative instructions are explained and used in the chapter, so the reader is not overwhelmed with details of instructions, mnemonics and the like.

Chapter 6 includes two actual programs, along with detailed explanations of what is being done by the programs and why. The real world is brought back into the picture with a program for the cassette controller. Illustrations of the controller hardware greatly aid comprehension. Since the cassette controller is basically a data collector, and since most processor-based industrial control devices are basically data collectors, an industrial data collection network is discussed in chapters 7 through 9.

The concept is discussed in chapter 7 with the aid of many sketches and block diagrams. The background (to which a majority of readers can probably relate) is developed into hardware, complete with a very detailed schematic diagram. While the schematic is impressive. I’m not quite sure why it was so detailed (including pin numbers, discrete component values, etc.). It seems very unlikely that a reader would actually undertake construction of the controller.

Having presented the hardware in chapter 8, the author presents a discussion of the software in chapter 9 (the entire assembly-language program, complete with copious comments, is presented in Appendix C). The book’s continuity stumbles a little here. All mnemonics used in previous assembly-language discussions have been based on the 8080 instruction set. Suddenly the Z-80 instruction set is introduced, along with a conversion table (from 8080 to Z-80 mnemonics) in Appendix A. There would have been less chance for reader confusion if the Z-80 had been used as the basis for all discussion.

That complaint notwithstanding, the author has done well to put the program listing out of the way in an appendix, so that the logical flow of the chapter is not interrupted. The chapter presents an excellent discussion of system software operation. The discussion is specific enough for the interested reader to be able to understand actual operation of the various program modules, but not so specific that the reader loses sight of overall system operations.

The concept of real-time operation, developed in the preceding three chapters, is elaborated on again with a different example in chapter 10. Some interesting concepts for industrial control are presented which the interested reader will probably want to pursue further.

Having discussed only industrial applications thus far in the book, the author presents his personal system in chapter 11. At first, a discussion of personal computers seems out of place, but given the intended audience, it helps to give the reader an overview of how the same microprocessor can be used outside the factory.

As any owner of a troublesome microprocessor system can attest, service seems to be an afterthought in any design. Chapters 12 through 17 are devoted exclusively to service—and how to design for it. These chapters alone make the book required reading for anyone about to design a digital system.

This book will probably have minimum appeal to the average hobbyist, but will appeal to anyone with a background in controls who needs to interface to (or design) a digital system. It is a welcome change from most digital books full of jargon and schematics.

You must be logged in to post a comment.