Mississippi Revisited

Computing Across America, Chapter 28

by Steven K. Roberts

April 8, 1984

We ain’t got no accent, man, but ah kin shore tell yore from the noath.

— Teenager in Vancleave, Miss.

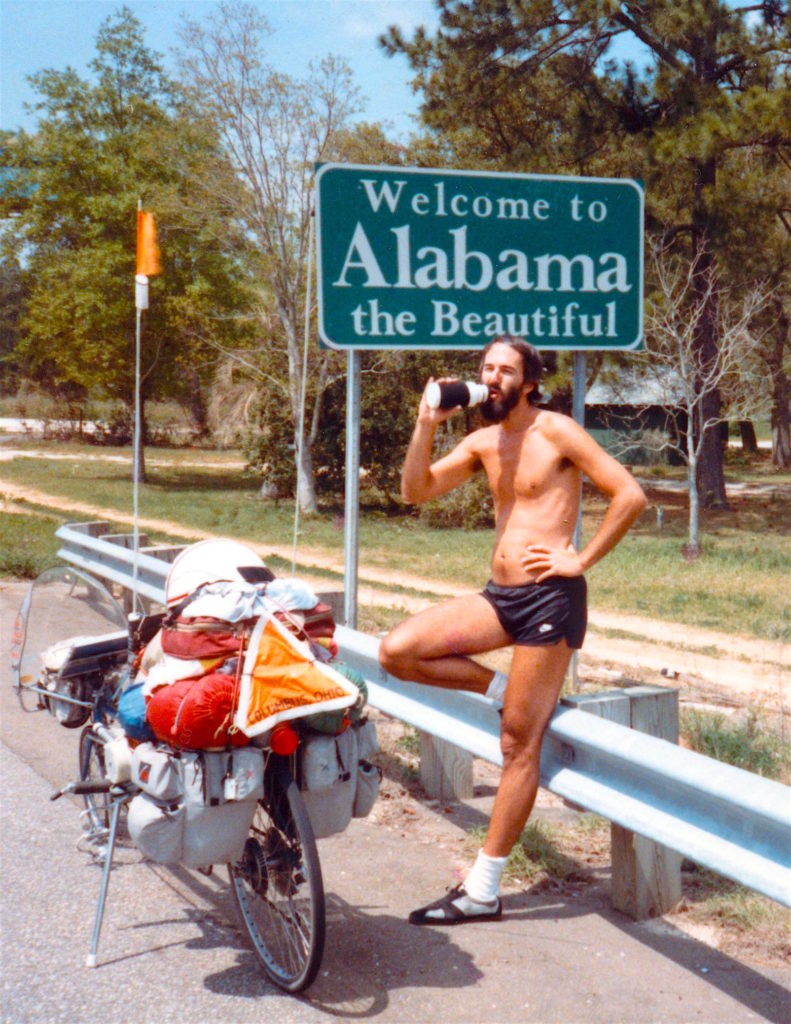

It was a land of spring green, little yellow flowers, and open, windy fields. I rode along with the sudden feeling of being really westbound, really in new territory. Alabama. The roadsigns were pocked with birdshot or tattered by 30-06 rounds, and the most popular greeting seemed to be: “Hey, dude!” The psychological effect of a “new state” was more pronounced than ever before: Alabama was Deep South.

After a short mail stop at Robertsdale to send postcards to my family, I continued west. There were thousands of cows and pigs; for at least ten miles I had the Beatles’ old “Piggies” song as an earworm until I banished it with one of my road-weary cassettes.

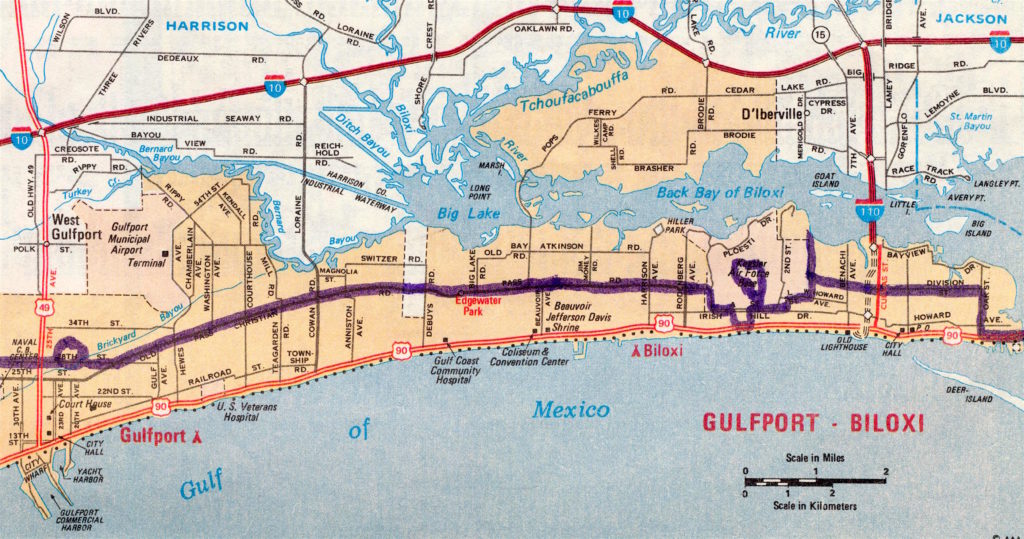

Arriving at Mobile Bay, I crossed the causeway at sunset and plunged illegally into the Bankhead Tunnel. The alternative was a detour of fifteen miles or so, and my knees and ankles were showing signs of imminent failure. Foolishly ignoring the NO PEDESTRIANS OR BICYCLES sign, I flew down into the earth over bumps and bicycle-wheel-eating storm gratings as the roar of traffic echoed from tile walls and heavy exhaust fumes caught in my throat.

I almost made it… almost. I pumped hard up the other side, struggling for fresh air with a Greyhound on my ass, hoping that the gratings wouldn’t grab a wheel and dump me under the bus. I pedaled hard, grimacing, wanting to hold my breath in the acrid fumes but desperate for oxygen. I was only about fifty feet from the exit when the blue lights struck — a cop going the other way had seen me. Damn it!

Lucky to be alive, I emerged from the tunnel and rode furiously, making it eight blocks on pure adrenalin before being stopped by cross traffic. The police car flashed to a halt, driven by a skinny version of Burt Reynolds in a southern cop costume. He peered out the window at me for a moment, said something into his microphone, then asked, “Tell me something: what are you doing in my tunnel on that thing?”

With a sheepish grin I replied, “Well, I didn’t see any signs and the traffic wasn’t too bad, so I thought I’d go for it.”

“Next time you get yourself a ride, or take alternate 90!”

“Will do — next time around the country. I’m enroute from Ohio to Europe, by way of Key West and San Francisco.”

He processed those locations a moment, then lifted himself off the seat and stretched to look at the bike. “On that?“

“Why sure!” I tooted the yacht horn and gave him a few flashes of my xenon strobe.

He shook his head in disbelief, questioning my sanity more than the miles. “Well, whatever. Just stay out of the tunnel on it.”

“No problem. So what’s the best way to get to the University of South Alabama from here? Old Shell Road?”

“You got it. Now you watch yourself, y’hear?”

An hour later, I arrived at the most sedate campus I’ve ever seen and pedaled around in search of the center of campus culture. None was to be found: no gathering place, few students. Finally, a trio of young women informed me that they were little sisters of Kappa Sigma, and that there was a party in the offing. Bingo! Kappa Sigma was the frat that had taken me in back in Washington, PA, after my first official dining hall routine.

I felt fully justified in calling to announce my arrival. Frats are like that, one of many networks of connections that lead to instant welcomes across the land. I rolled the bike into the rented suburban house (would you rent a house to a fraternity??? In southern Alabama?) and was quickly plunged into a beery party, surrounded by the accents and attitudes of the Deep South. The big event of the evening was the discovery that another frat had crashed their party for the free beer, whereupon the invaders’ van mysteriously broke down. By morning, it had been pushed deep into the weeds.

“Hey, them fuckers coulda got us in trouble,” one journalism major told me. “They got a law here — no open parties. We coulda got screwed for them drinkin’ our beer!”

Americana — April 6, 1984. Somewhere in the woods I hit Mississippi. Past a tiny town where shouting kids played in a ball field under a “Drink Coca-Cola” scoreboard, past vast stretches of open field and untouched forest, past perforated roadsigns and beer bottles in the ditch. Mississippi. Wow. I was only 24 hours from Florida, but the familiar was far, far away.

And just ahead was Louisiana: land of Easy Rider images, Cajuns, vast swamps, and more horror stories than any other state. Lots of people had warned me about lots of places, but everybody had warned me about Louisiana.

“You goin’ through Loosiana on that thing? You takin’ a thirty-ought-six with ya?” (What, so I can plink at road signs?)

But first, Mississippi. I had spent seven months of my brief flirtation with the Air Force here, twelve years before. The town names evoked images of weekends in my uniformed teens, chasing around the woods on a Honda 450 until a truck changed lanes on Highway 90 and broke my leg.

That was one of the motivations for the uncharted back-roads approach to my host’s house in Long Beach. I didn’t want to return to the scene of that accident in which a Bell helmet had prevented truck wheels from popping my skull like an underfoot June bug. I pedaled safely through rural, hilly calm, the rolling landscape refreshing after the long flat miles of Florida.

I arrived in Vancleave at about 3:30. This was a tiny town about ten miles inland from the Gulf, and at the shouted invitation of a dozen hootin’ and hollerin’ male teenagers I glided into a gravel parking lot. I had come a long way — these “rednecks-in-training” were guys I would have carefully avoided a few months earlier.

Drinking Bud and Boone’s Farm, leaning on their cars in the April sunshine, they began the interrogation. “Man, you talk funny,” one said.

“Me?” I paused thoughtfully for a moment. “I thought all you guys talked funny.”

“Shee-it. We ain’t got no accent, man, but ah kin shore tell yore from the noath! Where you comin’ from, anyhow?”

“Ohio.”

Another chimed in, his face screwed into a quizzical look as if trying to remember a distant geography lesson. “Ahia? Ain’t that up past Wiggins somewheres?” (Wiggins is about thirty miles from the Gulf.)

“I didn’t know you could get here from Ohio,” someone else observed philosophically, with more insight than he probably realized.

I bought a beer and joined ’em for a spell, careful to step over the “party line” — a cable in the parking lot — before opening the can. No drinking on liquor store property.

“You been mugged yet?” someone asked.

“No, I make friends pretty easy.”

“Well, you’re in the country for it.” The speaker, Ronnie, wrote his phone number on a piece of paper bag. “If you have any trouble, man, just give us a call.” Then he handed me the rest of the bag for my autograph.

I also autographed a Boone’s Farm label and a tattered hunting map, and stood enjoying their company, realizing that these were some of the people whom northerners had warned me about. They may have been of a different world, but they were genuine and likable.

I must have rhapsodized a bit on this theme, for one fellow said, “Well, man, if you think this is something, you oughta come back tonight! This whole parking lot fills up.” He swept his arm in a circle, then hoisted high his Budweiser. “Everybody drinkin’!”

I allowed as to how it sounded pretty exciting, and said that if Biloxi didn’t pan out, I just might come back. I crushed my beer can and lobbed it manfully into the dumpster, refastened my helmet, and headed for the water.

Before seeking the home of my Gulf Coast host, I needed to pay a pilgrimage to Keesler Air Force Base. It had been a strange time there — a time of freight-hopping, getting stoned, building music synthesizers in my barracks room, playing pranks on the humorless military, and, eventually, hobbling around on crutches. This was tech school, where I spent seven months learning how to be a black-box swapper on F-111 avionics systems. I recall pressing for details about the internal logic of a navigation computer one day, prompting the teacher to stamp her foot and cry, “Well honey, I don’ know how it do’s it, it just do’s it!”

Ah, education.

I rolled up to the gate, and the no-nonsense pistol-packing black female AP turned me away. Hey, I just want to see the ol’ place again — I used to live here.

I spent all that time trying to get out, and now they wouldn’t let me in.

I rode around to a different gate, via old Biloxi roads that are in worse repair than ever (bumpier than even the roughest parts of the C&O Canal towpath). At this gate, a bored AP waved me through when I told him I was there to demo the solar power unit at an inertial nav systems class party.

And nothing looked familiar. I couldn’t find the building I had lived in. I didn’t recognize the dining hall, the BX, or the main gate. The only familiar feature was the railroad… endless gleaming tracks just outside the perimeter that had always symbolized passage to somewhere else. I had traveled much in my mind back then: cloistered in a stark third-floor room, catching glimpses of infinity through tiny windowpanes, hopping around the globe via shortwave radio, and disappearing into the works of Huxley, Stockhausen, and Signetics.

I just didn’t have a chance to explore the base very much.

So I pedaled about, confused, stopping at a Baskin-Robbins (a Baskin-Robbins?) to eat a sundae and banter with a passel of AFC’s — all of whom seemed far too young to be in uniform. I felt old. This was a different reality, more like a college campus than that olive-drab tech school of the Vietnam era. A Baskin-Robbins?

I shook my head and rode freely away from the Air Force Base.

“People around here say that when you die and go to hell, your first stop is Atlanta.”

“Atlanta?”

“Yep. You always have to change planes in Atlanta to go north.”

It was dinner at the Hudson’s, and Bill had been keeping me laughing with his comments on places, politics, real-estate, social security, absurd liquor laws, and more.

Ex-wives: “We split 50-50—she took 50, then came back the next day for the other 50.”

Movies: “Well, I can’t watch that. It’s got Jane Fonda in it.”

Biloxi roads: “This state still uses the ‘beat’ system, which was adjudged antiquated in 1890. Everybody has his own little empire, and they don’t share equipment or funding. So you get excellent maintenance in the outlying areas and next to none in Biloxi and Gulfport.”

Bill and I met early in the trip, on the Lake Anne Plaza in Reston, Virginia. After a few minutes conversation, he had given me a business card and invited me to visit if I ever happened to ride through Gulfport, Mississippi. His name went into my hospitality database, popped up again at the Mississippi line, et voilá, here I was eating steak and enjoying his family.

My 3-day stay culminated in a windy beach party. Huddled against the blowing sand, we built a huge pile of scrap wood and pallets while the kids waited eagerly with marshmallows. The standard approach in these parts is to douse the whole affair with gasoline and toss in a match, but I made a tiny teepee-style campfire with scraps, starting it with a tissue and gradually adding dry pine. It didn’t take long in this powerful wind — within minutes sparks were sailing across the beach and dancing between the cars on Highway 90.

“Ooooh, freak-a-zoid!” cried 9-year-old Susan, somehow summarizing everything perfectly. “Freakydoodle,” added Candy, her colleague of the same approximate age. Together they did a little hand ballet, accompanied by the words, “Wah-wah, quack-quack, cockadoodle-do!”

I grinned up at them, mentioning that I had never heard those expressions before.

Susan crossed her arms in coy superiority. “There are a lot of things about me you don’t know.”

Again I felt old. I kept touching the past and finding it changed, glimpsing the future and finding it strange. I guess the only time that ever really makes sense is now.

You must be logged in to post a comment.