Nomadness – Technology on the Open Road – Recumbent UK

I had almost forgotten this article, tucked away in a binder with only its cover photo showing, but upon reading it I realize that the author did a masterful job of distilling my technical explanation of BEHEMOTH while it was still fresh… with clear and entertaining writing. Actually, I don’t even know the author’s name, but will add it to this page if a full issue turns up in addition to the tearsheet that I scanned for this archive post. (As always, page images are clickable for larger versions if you want a better look at the photos and their captions.) The bike version described here is the one that rolled out of the lab in 1991, though the article was written in 1998. The lead photo was from a shoot for Bicycling Magazine.

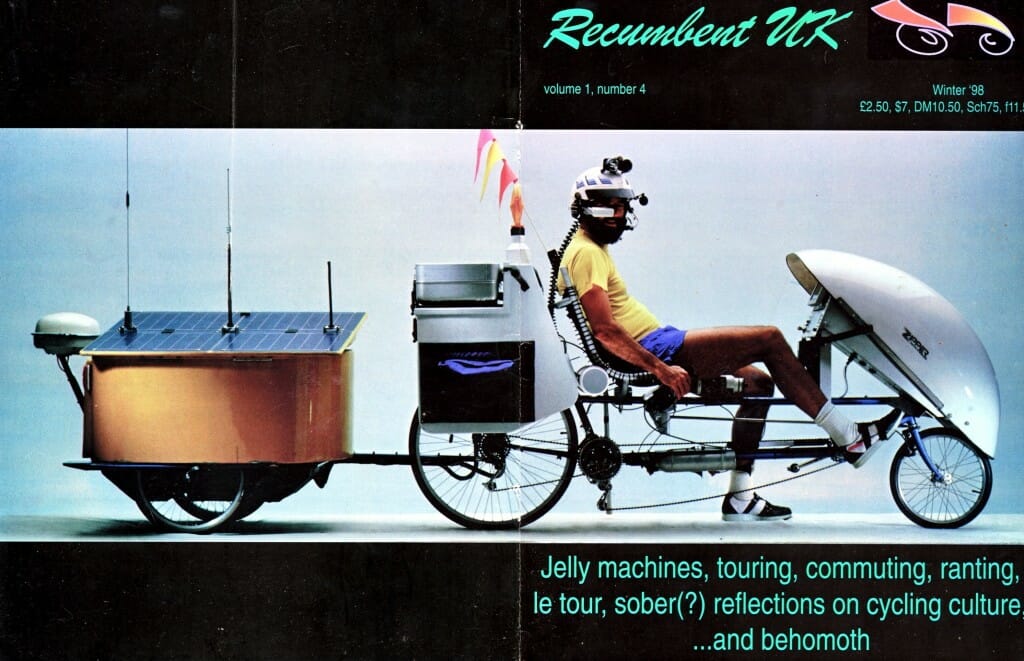

Recumbent UK

Winter, 1998

1983 – Steve Roberts wasn’t enjoying suburban life. The dawn chorus of motor mowers was just getting to him – worse, he wasn’t enjoying having to pay for it. He did the one sane thing he could in the circumstances, had a touring cycle built up for him, sold everything that wouldn’t fit onto the bike and pushed off on a 10,000 mile tour of the United States.

This did leave the slightly sticky problem of how he was going to pay his way, but again, inspiration came easily. He equipped the bicycle with a radio system and a computer, intending to carry on writing and consulting on computer systems design to earn his daily bread. The Winnebiko was born, a custom long-wheelbase recumbent equipped with a ham radio, a Radio Shack Model 100 laptop, and a small solar array for power.

Today, when you can hook up a cell-phone and a palmtop PC to provide reliable voice and data communications across most of Europe and the US (and with Iridium, now the world) this doesn’t seem terrifically new or exciting. In 1983 it was revolutionary. Offices – where you worked – were static things, buildings and desks and cubicles and secretaries, all sitting in roughly the same place. Electronic mail was in its (popular) infancy; outside academia, the thought of entrusting important, let alone confidential communications to a collections of beeps and whistles was unthinkable. Steve set off to prove that it was not necessarily important where your body was, provided you could maintain reliable network communications.

Downloading email from public pay phones and uploading his writing quickly became a way of life. For the next 10,000 miles, Steve crisscrossed the USA. He did manage to make a living, but as he rode and wrote further, the limitations of the Winnebiko became more and more frustrating. Writing was only possible when the bike was stationary, computer based communications were tied to public telephone boxes and that 5 watt power budget, well….

And so the Winnebiko II came into being. With a bundle of microprocessors, a packet radio based communications system (freeing the bike from the telephone booth), solar panels capable of generating 20 watts on a fine day and a satellite based navigation system. Steve could now write on the move (via a one handed chord keyboard), as well as communicate.

The problem with improving the bike’s on-board system was that outside world was suddenly changing, and quickly. The Winnebiko II was beginning to show its age. It was difficult to maintain, difficult to extend, and the single liquid crystal display (just one!!!) too limiting.

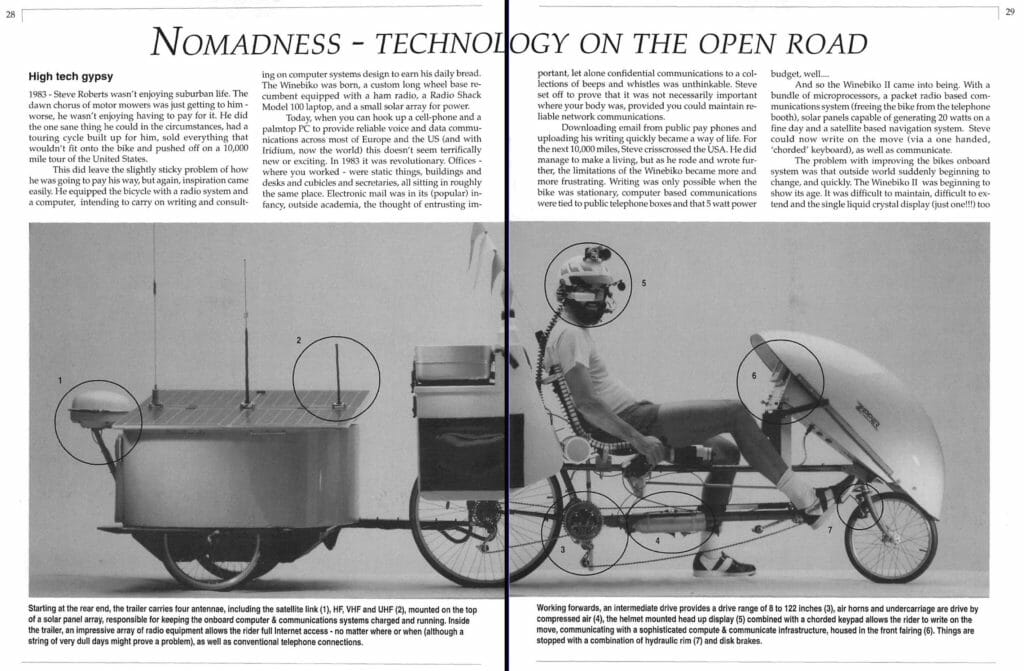

And so to BEHEMOTH (Big Electronic Human Energised Machine… Only Too Heavy). BEHEMOTH is an 8 foot recumbent (the original Winnebiko) with under seat steering, hydraulic brakes and landing gear that deploys automatically at low speeds. The bike tows a 4 foot trailer carrying the communications system, solar panels and antennas. The fairing houses three LCDs and instruments that keep Steve in touch with each part of this system all the time. On top of his head, a specially designed helmet carries an eye mounted display (for writing on the move – no need to look down), an audio system and even a heat exchanger for keeping his head cool under load (no comment).

GRATUITOUS SPECIFICATIONS

And so to the meat of the article – a tour of the whole machine, an end to end, pedal to fairing tech-fest. Gratuitous maybe, but at least 50% of the purpose of BEHEMOTH is the technology – feel free to skip to the end!

The Bike

The bike, the bike. The weight (loaded) of the complete machine – without rider – is 260 kg (570 lbs) – not surprisingly this puts certain strains on conventional components and materials.

The frame is made from custom tandem tubing and was purpose built by Jack Trumbull of Franklin Frames in Ohio. With the type of load that Behemoth carries, getting started, and stopping is an area of concern.

Starting happens via triple derailleur – not to mention a set of large legs – crossed over (not the legs – the chain set) and providing a gearing range of about 8 to 122 inches. (8 inches gives you a speed of about 1.2mph @ 60 rpm – sufficiently low for most hills.) In practice, the bike cruises at a comfortable, if not hare-like 12 mph on level ground.

Of course having introduced such a low bottom, the next problem is one of balance – BEHEMOTH is not a tricycle, and at slow speed becomes unstable. Not afraid of going for techno-overkill, Steve chose to use pneumatically deployed ‘landing gear’, a pair of small wheels on either side of the beast that can be dropped at low speeds to provide stability, and then used as parking wheels when stopped.

So, up to speed, and the next problem is losing it. 260kg at 20 mph has a lot of kinetic energy and a great deal of thought has been put into the braking system. For ‘normal’ use, a pair of Magura hydraulics driven from conventional hand levers slows the bike. A hydraulic disk on the rear wheel allows speed to be regulated on long hills without heating the rear rim, and a mechanical brake is used both as backup and to provide a parking brake.

Steering is conventional – for an under seat steered long wheelbase. A single steering rod is linked from the handlebars to the fork crown. These handlebars (and the nearby seat frame) carry much more than the normal bicycle controls, of course. There are three shift levers, the parking brake lever, hydraulic brake levers, and 7 keyboard buttons on each side. The right thumb has a button for the twin air horns; the left has push-to-talk radio.

The bike relies both on its size and on efficient lighting and sound systems to ensure everyone knows it is on its way. Air horns are fed from a dedicated pressure tank (it leaves the Air Zound well behind in the dB race). Lighting is provided by a combination of a sealed-beam quartz-halogen headlight, two Night-Sun lights (spot and flood) mounted on the helmet, a strobe on the antenna mast and high performance LED tail and turn lights on the rear end.

Loaded, wheels and bearings take a battering. The rear wheel is a 48 spoke undished unit built around a sealed hub. This has proved itself over more than 17,000 miles, never breaking a spoke and just needing occasional truing and tightening. The headset is a Chris King, an upgrade from the previous choice (which seemed to last 500 miles or less between replacements). The front fairing (with all of its delicate equipment packed inside) is shock mounted.

Computing & Control

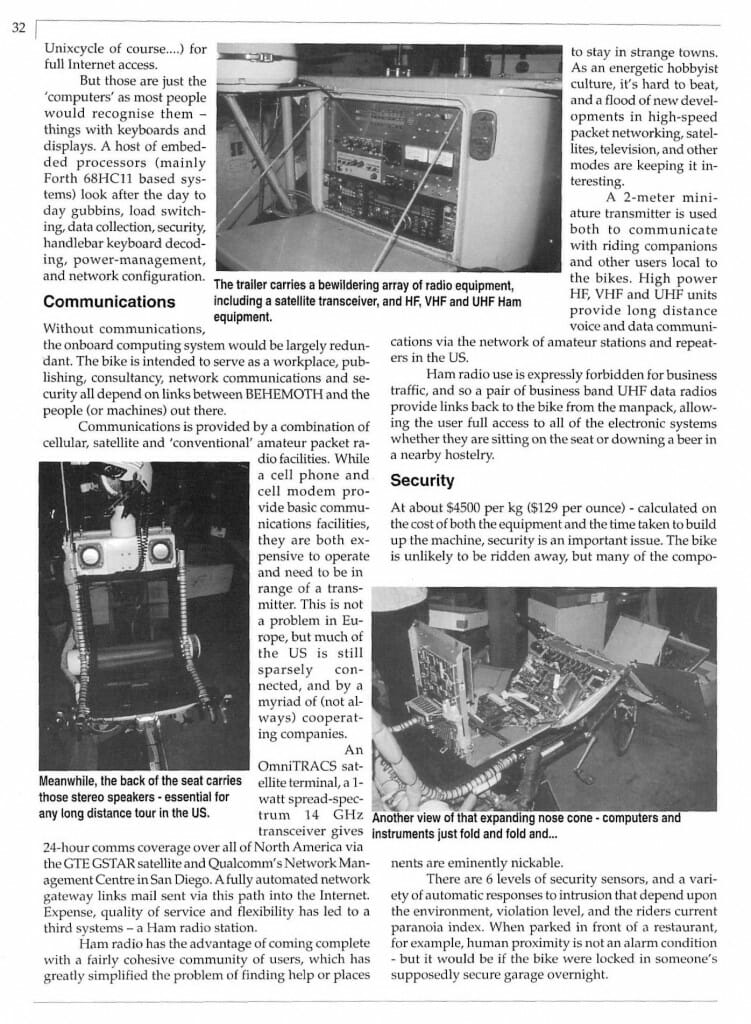

The heart of BEHEMOTH is a collection of microprocessors, responsible for running everything from the communications subsystem through the alarm and word processing platforms.

The primary user interface is based around a Macintosh portable computer, whose hinged screen is at the top of the control console. Mouse pointing is achieved by either head movements (the helmet has ultrasonic motion sensors built into it) or via a joystick on the handlebars. Data entry is via the handlebar keyboard that serves all machines, or a plug-in QWERTY keyboard for use when stationary. The handlebar keyboard is a ‘chorded’ 7 key pad – you type by forming patterns on the keyboard rather than allocating one character to each button.

The bike’s control software is heavily based around the control language ‘Forth’ and Apple’s proprietary visual scripting language/system, HyperCard. All bike control is represented through a variety of views, each bearing graphic elements that are linked through external commands to the bike’s trio of control systems. These control views are divided along application boundaries, such as security, power, network configuration, maintenance, data collection, ham radio, packet datacomms, and so on. The point of all this is complete flexibility in interface design (the precise opposite of the Winnebiko II, whose hardwired console was virtually impossible to modify.)

Other Mac applications include biketop publishing, Eudora for electronic mail, word processing, communications, MIDI system control, and a slide show of graphics and scanned ‘electronic sponsor decals’ for use when BEHEMOTH is on public display.

Flipping up the Mac screen reveals a Sharp VGA LCD driven by an Ampro Little Board 286 system, essentially a 16 MHz AT-class DOS PC packaged for industrial control and drawing about 8 watts (including a maths coprocessor, 4 megabytes of RAMdisk, 3.5-inch floppy, and a second shock-mounted Conner 40 meg hard drive). The backlit screen allows any robust DOS graphics application to execute perfectly well on the bike. This translates into easy use of OrCAD, Autocad, programmable gate array software, computer-generated maps, and much more.

A second DOS system, located behind the seat, runs a number of applications including Reference File, a pop-up database manager that allows him instant access to about 5,000 contacts around the world. Since this was in frequent use on the road, it lives in the system that drives the heads-up display on the helmet – Reflection Technology’s Private Eye. This 720X280 screen presents the illusion of a floating display just below the riders centre of vision, no matter where he happens to be looking (even in rain, darkness, or direct sunlight).

The console also carries a third DOS system, based on the innards of a Toshiba T1000. It may seem redundant, but remember the power-management problem – often all that is needed is a simple large-print text editor (Eye Relief) or communication program. This also runs the Covox speech-recognition system, enabling voice command of basic bike functions via helmet or remote radio (but not continuous text entry, not quite yet…).

A fourth machine, a Macintosh PowerBook is carried in the trailer, allowing routine text work and software development when off-bike with the manpack. It also allows full remote control of the on-board systems from up to 2 miles away via a business-band packet data link.

Finally (really and truly), a Sun Microsystems SPARCstation provides a workhorse for computer aided design and map generation. It also provides a node (a Unixcycle of course….) for full Internet access.

But those are just the ‘computers’ as most people would recognise them – things with keyboards and displays. A host of embedded processors (mainly Forth 68HC11 based systems) look after the day to day gubbins, load switching, data collection, security, handlebar keyboard decoding, power-management, and network configuration.

Communications

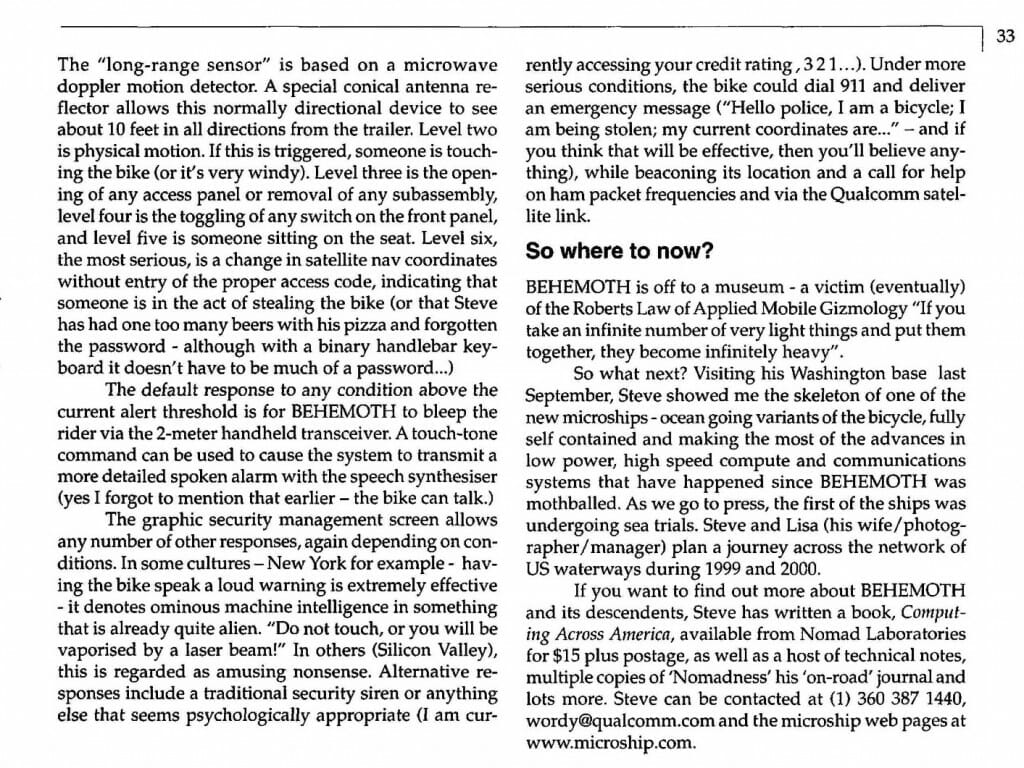

Without communications, the onboard computing system would be largely redundant. The bike is intended to serve as a workplace, publishing, consultancy, network communications and security all depend on links between BEHEMOTH and the people (or machines) out there.

Communications is provided by a combination of cellular, satellite and ‘conventional’ amateur packet radio facilities. While a cell phone and cell modem provide basic communications facilities, they are both expensive to operate and need to be in range of a transmitter. This is not a problem in Europe, but much of the US is still sparsely connected, and by a myriad of (not always) cooperating companies.

An OmniTRACS satellite terminal, a 1-watt spread-spectrum 14GHz transceiver gives 24-hour comms coverage over all of North America via the GTE GSTAR satellite and Qualcomm’s Network Management Centre in San Diego. A fully automated network gateway links mail sent via this path into the Internet. Expense, quality of service and flexibility has led to a third system – a Ham radio station.

Ham radio has the advantage of coming complete with a fairly cohesive community of users, which has greatly simplified the problem of finding help or places to stay in strange towns. As an energetic hobbyist culture, it’s hard to beat, and a flood of new developments in high-speed packet networking, satellites, television, and other modes are keeping it interesting.

A 2-meter miniature transmitter is used both to communicate with riding companions and other users local to the bikes. High power HF, VHF and UHF units provide long distance voice and data communications via the network of amateur stations and repeaters in the US.

Ham radio use is expressly forbidden for business traffic, and so a pair of business band UHF data radios provide links back to the bike from the manpack, allowing the user full access to all of the electronic systems whether they are sitting on the seat or downing a beer in a nearby hostelry.

Security

At about $4500 per kg ($129 per ounce) – calculated on the cost of both the equipment and the time taken to build up the machine, security is an important issue. The bike is unlikely to be ridden away, but many of the components are eminently nickable.

There are 6 levels of security sensors, and a variety of automatic responses to intrusion that depend upon the environment, violation level, and the rider’s current paranoia index. When parked in front of a restaurant, for example, human proximity is not an alarm condition – but it would be if the bike were locked in someone’s supposedly secure garage overnight.

The “long-range sensor” is based on a microwave Doppler motion detector. A special conical antenna reflector allows this normally directional device to see about 10 feet in all directions from the trailer. Level two is physical motion. If this is triggered, someone is touching the bike (or it is very windy). Level three is the opening of any access panel or removal of any subassembly, level four is the toggling of any switch on the front panel, and level five is someone sitting on the seat. Level six, the most serious, is a change in satellite nav coordinates without entry of the proper access code, indicating that someone is in the act of stealing the bike (or that Steve has had one too many beers with his pizza and forgotten the password – although with a binary handlebar keyboard it doesn’t have to be much of a password…)

The default response to any condition above the current alert threshold is for BEHEMOTH to bleep the rider via the 2-meter handheld transceiver. A touch-tone command can be used to cause the system to transmit a more detailed spoken alarm with the speech synthesiser (yes I forgot to mention that earlier – the bike can talk.)

The graphic security management screen allows any number of other responses, again depending on conditions. In some cultures – New York for example – having the bike speak a loud warning is extremely effective – it denotes ominous machine intelligence in something that is already quite alien. “Do not touch, or you will be vaporised by a laser beam!” In others (Silicon Valley), this is regarded as amusing nonsense. Alternative responses include a traditional security siren or anything else that seems psychologically appropriate (I am currently accessing your credit rating, 321…). Under more serious conditions, the bike could dial 911 and deliver an emergency message (“Hello police, I am a bicycle; I am being stolen; my current coordinates are…” – and if you think that will be effective, then you’ll believe anything), while beaconing its location and a call for help on ham packet frequencies and via the Qualcomm satellite link.

So where to now?

BEHEMOTH is off to a museum – a victim (eventually) of the Roberts Law of Applied Mobile Gizmology “If you take an infinite number of very light things and put them together, they become infinitely heavy”.

So what next? Visiting his Washington base last September, Steve showed me the skeleton of one of the new Microships – ocean going variants of the bicycle, fully self contained and making the most of the advances in low power, high speed compute and communications systems that have happened since BEHEMOTH was mothballed. As we go to press, the first of the ships was undergoing sea trials. Steve and Lisa (his wife/photographer/manager) plan a journey across the network of US waterways during 1999 and 2000.

If you want to find out more about BEHEMOTH and its descendents, Steve has written a book, Computing Across America, as well as a host of technical notes, back issues of Nomadness, his ‘on-road’ journal, and lots more.

You must be logged in to post a comment.