On the Virtual Road – Internet Underground

I love this article. The author does a wonderful job of introducing the pioneers of net-connected travel, each breaking new ground in different ways. Re-reading this 16 years after it was published, I want to throw a party for my fellow paleo-technomads… it’s been a long road, even wilder than any of us imagined! I enjoyed reading Jeff Greenwald’s observation that “What we’ll see in the near future, I think, is a kind of information backlash: Travelers will purposefully disconnect themselves and revel in the idea of sojourning without a net, so to speak.” I have often joked that I could get another spirited round of media coverage now by pedaling across the US without any technology. Instead of asking “why on earth would you want a computer on a bicycle?” as they incredulously did back in 1983, they’d ask in amazement: “but.. but… how do you get your email and keep up with Facebook?” A lot has changed in a generation…

The bike represented the outrageous notion that very soon now, it might not matter where your body happens to be… as long as you maintain a presence in the networks.

Anyway, if you’re interested in some of the foundations of technomadics, location-independent business, and the ubiquitous communication toolsets that we now carry in our pockets and take for granted, read this. It’s a good one.

The article is posted here with permission of Michael Shapiro, who has been prolifically travel-writing for decades and is the author of A Sense of Place (a goldmine of insights from travel writers) and The Creative Spark.

On the Virtual Road

by Michael Shapiro

Internet Underground – October, 1996

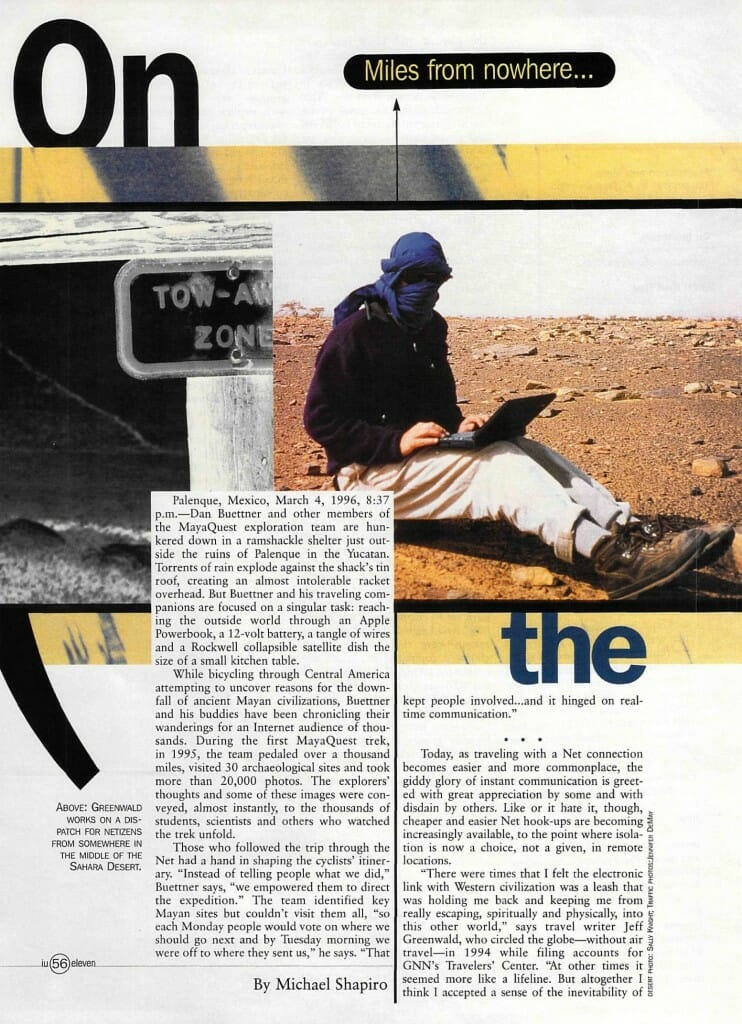

Palenque, Mexico, March 4, 1996, 8:37 p.m.—Dan Buettner and other members of the MayaQuest exploration team are hunkered down in a ramshackle shelter just outside the ruins of Palenque in the Yucatan. Torrents of rain explode against the shack’s tin roof, creating an almost intolerable racket overhead. But Buettner and his traveling companions are focused on a singular task: reaching the outside world through an Apple Powerbook, a 12-volt battery, a tangle of wires and a Rockwell collapsible satellite dish the size of a small kitchen table.

While bicycling through Central America attempting to uncover reasons for the downfall of ancient Mayan civilizations, Buettner and his buddies have been chronicling their wanderings for an Internet audience of thousands. During the first MayaQuest trek, in 1995, the team pedaled over a thousand miles, visited 30 archaeological sites and took more than 20,000 photos. The explorers’ thoughts and some of these images were conveyed, almost instantly, to the thousands of students, scientists and others who watched the trek unfold.

Those who followed the trip through the Net had a hand in shaping the cyclists’ itinerary. “Instead of telling people what we did,” Buettner says, “we empowered them to direct the expedition.” The team identified key Mayan sites but couldn’t visit them all, “so each Monday people would vote on where we should go next and by Tuesday morning we were off to where they sent us,” he says. “That kept people involved… and it hinged on real-time communication.”

Today, as traveling with a Net connection becomes easier and more commonplace, the giddy glory of instant communication is greeted with great appreciation by some and with disdain by others. Like or it hate it, though, cheaper and easier Net hook-ups are becoming increasingly available, to the point where isolation is now a choice, not a given, in remote locations.

“There were times that I felt the electronic link with Western civilization was a leash that was holding me back and keeping me from really escaping, spiritually and physically, into this other world,” says travel writer Jeff Greenwald, who circled the globe—without air travel—in 1994 while filing accounts for GNN’s Travelers’ Center. “At other times it seemed more like a lifeline. But altogether I think I accepted a sense of the inevitability of that kind of contact because we’ve entered an age where removing yourself from the world at large is an affectation, not a reality. Whereas 50 years ago you could really go to places and be genuinely cut off and isolated, nowadays it’s a choice you make.”

Whether one views those wires as a lifeline or a leash, Net communication is opening new horizons for global explorers as well as for those on the receiving end of these dispatches, who, with the click of a mouse, can travel from the frigid waters of Antarctica to the tropical rain forests of Central America to the peaks of Mt. Everest.

Serious Net travel probably began back 1983, when Steve Roberts, bored with suburban life around Columbus, Ohio, and struggling with a freelance writing career, decided to make himself a list of his passions. “Freelancing was an illusion,” he says. “I was chained to my desk and deep in debt like everyone else. Stuck.” His passion list included writing, adventuring, computer design, bicycling, networking and publishing.

After abandoning “all rational thought,” the answer to Roberts’ malaise became clear. He slapped a Radio Shack portable computer onto a recumbent bicycle, established a “home” on the nascent CompuServe network and began to travel full-time while writing and consulting for a living. This early technology soon became insufficient, and Roberts eventually built a new bike: the 580-pound BEHEMOTH (Big Electronic Human-Energized Machine… Only Too Heavy).

The 105-speed recumbent has a Mac, PC and a Sparc station (“I always wanted to ride a UNIX-cycle,” he quips). “It all runs on solar panels—I can be in the middle of the Utah desert and be just as in touch as anywhere else,” Roberts says. Yet there can be some disadvantages to traveling with such an outrageous Net connection. Roberts is peppered with endless questions. “Are you with NASA?” asked an Iowa farmer.

Overall, Roberts has relished his mobile connectivity and says it has enriched his lifestyle—which he calls “nomadness”— beyond his wildest hopes. “Nomadness is the most social lifestyle imaginable for two reasons: global networking and the timeless energy of beginnings. The traditional concept of stability, normally restricted to neighbors, associates, and the familiar things that define home, is now distributed around the world and constantly refreshed by encounters on the road. Home is everywhere, and I am constantly amazed by the intelligence and imagination lurking in the most unlikely places.”

Thirteen years and 16,000 miles later, Roberts, author of the 1988 book Computing Across America, is turning his energy toward creating the Microship, a fully-equipped boat that will allow him to continue his traveling, writing and networking from the world’s waterways.

Like Roberts, Jeff Greenwald sought an escape. While Greenwald’s routine of traveling to the far corners of the globe wouldn’t appear mundane to most, he felt he’d become more a commuter and less an adventurer. As his 40th birthday approached, Greenwald decided to make a devotional kora, a pilgrimage around the most sacred object he could think of: the planet Earth. To get away from the rut of commuting, he chose to completely avoid air travel and circumnavigate the globe with on-the-ground transport: trains, boats, cars, mules and even his own two soft-soled feet.

He acknowledged the irony of using the latest computer technology to get his dispatches to readers through Global Network Navigator, a guide to online resources created by O’Reilly & Associates. “The point of my trip was to forsake technology, so my reliance on technology and my presence on the Web became an ironic counterpoint to this journey. While my brain was telecommuting at the speed of light, my body was still compelled to travel at a snail’s pace, face down in the sand.”

There were days when Greenwald cursed the wires, couplers and laptop he dragged with him during his quest. “I spent an entire festival day in the town of Oaxaca (Mexico) trying futilely to send a dispatch to GNN: endless tries, as much technical support as they could give me, and a fortune in telephone calls amounted to absolutely nothing. It was a really good example of how I could waste half of my trip trying to deal with the logistics of the Internet, which was then, only two years ago, in a much more primitive state than it’s in now.” (Greenwald later realized that the entire fiasco may have been due to his failure to flick a switch from tone to pulse.)

At other times, however, Greenwald was ecstatic that as he traveled through Guatemala, Istanbul and Tibet, he could share his adventures—almost instantaneously—with friends, family and fascinated readers. “I had this sense of being almost on fire, that the excitement and heat of my journey was providing me with something I could broadcast in no time at all,” he says. “It was a very giddy feeling.”

Occasionally, Greenwald’s dispatches went far beyond his insightful observations to solid news reporting of events with broad human rights ramifications. He arrived in Tibet shortly after President Clinton agreed to “de-link” China’s human rights record with the country’s application for Most-Favored Nation status. “It was amazing to be able to write for immediate publication about the way the Chinese were gloating and about the way they were oppressing the Tibetans even more now that they felt America had stepped away from the fight,” he says. “I felt a real sense of responsibility and privilege to be able to convey that information.” Greenwald chronicled his entire trip in The Size of the World, published earlier this year by Globe Pequot Press.

Others have set out with a specific social agenda. Porter Gale and Donna Murphy embarked last spring on a bike ride to raise awareness about breast cancer. Dubbed “2 Chicks, 2 Bikes, 1 Cause,” their 5,000-mile bike ride sought a much larger audience than the people they met as they pedaled across the United States. The two women used the Net to target a global audience.

“Usually the Net is an anonymous vehicle, but we’ve met people and become really close friends,” Gale says during an en-route interview as the pair approached Des Moines, Iowa. Gale and Murphy altered their route to intersect with a young woman who was doing a similar ride after her mother died of breast cancer.

The pair also cite a simple benefit of the Net that appeals to many travelers in distant lands: “It’s really good for staying in touch with our families—we can let them know we’re safe.”

Diane MacEachern, an environmental journalist, joined the TerraQuest expedition to the Galapagos to help promote preservation of the islands and their inhabitants. While she used the Net to help spread this message, she was amazed by the technical advances and got a crash course in new multimedia tools. “I went into it thinking only of images and words,” she says. But MacEachern soon realized the team could include sounds, from the whisper of the winds to the roar of a sea lion: “Now it seems incomplete to just have words and pictures.”

While sending Net dispatches can be exhilarating for technomads, following these dispatches is often riveting for Net surfers. For some users, who may be old or ill, it can be as close as they’ll get to faraway lands, the next best thing to being there. For others it’s a way to get a first glimpse of a region they hope to soon visit. And for some, it’s simply the thrill of participating in a great adventure.

Last May, a Net audience of thousands joined the celebration as a team of climbers led by Seattle-based mountaineer Scott Fischer reached the summit of Mt. Everest. Yet within hours, exultation turned to despair as a fierce snowstorm blanketed the high camp where Fischer and others rested. The gripping saga played out over the Net as rescuers found Fischer and climbing companion Makalu Gao clinging to life, carabinered to one another. Only one man could be saved, and since Fischer was already comatose, rescuers chose Gao, put some blankets over Fischer and descended. Eight climbers were eventually found dead.

“As the horror started to unfold, I felt my heart sagging with despair,” wrote a Net-surfer named Jilly. “I felt so close to what had happened and felt a strange kinship with these souls.”

More typically, using the net to connect with people who are traveling is inspiring and uplifting. Just ask Greg Elin, who during the fall of 1995 embarked on a transcontinental motorcycle ride across the United States called “Silicon Alley to Silicon Valley.” Elin set out to prove that people could access the vast stores of electronic info without remaining chained to their desks. Using a Connectix camera mounted to his motorcycle helmet, Elin continually broadcast images to his Web site.

“Until now, the legacy of the information age—which has given the individual access to vast amounts of knowledge and power—has been a type of bondage,” he said. “Bondage to the terminal, to the telephone, to the fax machine.” His trip and the journeys of others have helped “demonstrate that technology has escaped its cage of wires.”

During his trip, Elin found time to visit his parents in Chicago, set up their new computer and get them on the Net. A week and a half later, he pulled his motorcycle to the side of the road, took a digital photo of a stunning sunset and quickly uploaded the image to his Web site. Within minutes his mother and his girlfriend saw an image of the sunset Greg had just witnessed.

“It has the potential to be so personal,” he says. “All I needed was a computer, the Net, a phone and a camera, and they were seeing live pictures from my motorcycle in New Mexico.”

Over and over, travelers who take the Net with them emphasize how outstanding a tool it is for making personal connections. “The Net is not this faraway vision of cyberspace, but real people you can visit,” Elin says. And keeping that connection alive leads to making more connections as one travels, helping solidify those serendipitous and sublime encounters that can be the most rewarding times of a journey.

Travel Log-In

Jeff Greenwald and Steve Roberts are pioneering world travelers who were among the first to send dispatches to an Internet audience. Roberts began “traveling wired” in 1983 after strapping a Radio Shack portable to his recumbent bike and getting an account on CompuServe. In 1994 Greenwald embarked on an around-the-world trip, without air travel, and broadcast his impressions through Global Network Navigator (GNN).

Following are some of their impressions:

Steve Roberts: In a small way, the bike represented the outrageous notion that very soon now, it might not matter where your body happens to be…as long as you maintain a presence in the networks….Home, quite literally, became an abstract electronic concept. From a business standpoint, it no longer mattered where we were, and we traveled freely, making a living through magazine publishing and occasional consulting spin-offs, seeking modular phone jacks at every stop.

Jeff Greenwald: It’s very important to realize that being in communication with people via the Internet does not mean they can do anything to help you necessarily. If a bunch of natives in some South American country had decided to put me in their stew pot, all the communication in the world wouldn’t have gotten me off the menu.

SR: People are endlessly fascinated by life on the edge, the adventures of travelers and peeks through curtains into other lives. Travel and writing are thus inextricably linked, and by carrying the most sophisticated tools available for biketop publishing, communication and information-gathering, I minimize the number of excuses for not being productive while raising reader curiosity in the process. For an author, this whole gambit is a gold mine: endless story material, superb tools and easy marketing based on a recognizable image.

JG: We’re going through a period with the Internet where people are so enamored with it that they’re painting the town red with info—they just want info to be sent from all parts of the world just to show it can be done. We know it can be done. What we’ll see in the near future, I think, is a kind of information backlash: Travelers will purposefully disconnect themselves and revel in the idea of sojourning “without a net,” so to speak. Instant co-communication will no longer seem novel but invasive. In many ways I consider the Internet to be the ultimate computer virus.

SR: The rhythms of movement beat like an undercurrent of congas in the night: heart thumping, pedal pumping, file dumping. New towns roll into view, effortlessly, each a haven of new friends and warm beds…Each a different view of the same essential home. I write, add bike systems and expand the family. And it’s so easy, this nomadic life, now that the desperation is gone and the tools are familiar.

JG: (On unplugging) It’s easier said than done—human beings are highly communicative animals, and communication becomes addictive. Ifs very difficult to be in an unfamiliar place where you can communicate and not communicate. And information seems to breed information—the more you communicate with people, the more they communicate with you. After four weeks in Kathmandu, I was answering 16-25 e-mail messages a day and spending two to three hours in my little office when I could have been outside visiting temples and day hiking in the Himalayas.

JG: (On traveling wired today) When I was doing this two years ago, the idea of sending back dispatches via the Net was pretty exotic. Nowadays, when I see people sitting around in remote corners of the world and typing away on their notebooks, I roll my eyes. Being wired has become a kind of cliche; and it can certainly distance you from the Here and Now. I get lots of e-mail from people asking how they can stay in continual real-time contact with their friends, lovers and editors. “Leave your laptop at home,” I tell them, “and enjoy your trip. You’ll have a much better time staying footloose, keeping your eyes open and writing the occasional postcard.”

You can learn more about Michael Shapiro, the author of this article, here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.