Online: A Smorgasbord of Services

In the before times, not only pre-Google but pre-Internet, our tools for online research were esoteric and expensive. In 1982-83 I was obsessed with this technology, and was not only running a small “information brokerage” business but writing articles about how to put these resources to use (along with emerging issues, like downloading). This piece came out in CompuServe’s Online Today magazine when I was a month or so into my bicycle adventure, and it was intended as an introduction to sorting through the huge range of options.

by Steven K. Roberts

Online Today

November 2, 1983

One of the first things you are likely to discover upon investigating the online field is a bewildering variety of available databases. Most are excellent — but many overlap, some are virtually useless, and others are so difficult to use effectively that they are best left alone.

A look through the 1,242 pages of the 1983 Encyclopedia of Information Systems and Services (a directory published by Gale Research Co.) reveals detailed information on over 2,500 information providers. A recent issue of Learned Information’s Online Review listed pricing updates on 276 separate databases, and in the process of researching a recent book, my coauthors and I accumulated a stack of user’s manuals and sales literature over six feet tall.

That is a lot of information. How can you possibly assess your needs and intelligently take advantage of unfamiliar resources in such a rapidly changing and dynamic industry? It is easy to be misled by an overzealous vendor of something that you don’t really want, only to suffer a rebound effect wherein you conclude that the whole technology is inappropriate to your operation. This has happened time and time again with microcomputers, and is now occurring in the online information field as well.

This article is intended to demystify the on-line business somewhat — first by explaining the three database classes, and then by noting the steps you should take to match your needs to the services that exist.

The Three Major Database Classes

If we seek distinctions that can be used to create manageable categories from this profusion of available services, we quickly discover that there are three distinct “styles” of database: full-text, bibliographic, and what we might call “just the facts.” Let’s have a look.

Full-Text Databases

The most obvious form of on-line database would seem to be that of the “full-text” variety, wherein the complete text of an article or other document exists somewhere in the system and is just available for recall. After all, that’s what you are most likely to be seeking when you sign on and start spending money — the information itself, not just references to it.

Unfortunately, however, full-text databases are relatively uncommon. There are a number of good reasons for this.

First, from a purely economic standpoint, the storage of all that text would require thousands of times the disk capacity now available to the on-line vendors. This would be unreasonably expensive in light of anticipated usage levels and thus difficult to amortize.

Second, you probably wouldn’t really want everything to come over the phone to your terminal in full-text form, not when you are paying a dollar or more a minute for transmission time. A typical 4,000-word magazine article would take roughly 13.3 minutes to arrive in full at your 300-baud terminal — which at the rate of a typical database would cost you about $18. That may be a perfectly acceptable cost for the final result of your search, but not for all the extraneous material that you are likely to pick up in the process.

Third, an abstract of an article generally includes some features that are not found in the original text itself. One of the jobs of the abstractor is the selection of key descriptor phrases from a controlled vocabulary, which then become part of the on-line record. This enables you to find an article about the consumption of hominy grits in Alabama during your search for information about grocery marketing in the southern United States. It also allows you to browse through a number of records with a fair degree of cost-effectiveness (something that would be hard to do at $18 and 13 minutes apiece).

But the fact remains that full-text is generally considered the ultimate objective of one’s research activity, and it is to this end that document delivery vendors exist in the industry. These folks will provide full-text copies of original source material — often accepting orders via the on-line services themselves and shipping the results within a day.

There are some significant full-text databases out there that you should know about. On the DIALOG system, you can search their monthly Chronolog newsletter, another journal called the Online Chronicle, and the Harvard Business Review. You can also access the full text of UPI News and the PR Newswire.

The best known of the full-text databases, however, are probably the ones offered by Dayton-based Mead Data Central: LEXIS and NEXIS. The former is a legal and accounting research service that has been available since 1973; the latter is a news service. Consisting of the full text of all articles appearing on AP, UPI, Reuters, PR Newswire, Kyodo, Jiji, and other news services, as well as various newspapers, newsletters, and magazines, NEXIS provides five or more years of background on virtually every subject that makes it into the news. Records appear on the screen in KWICK (Key Word In Context) style, with search terms that you specified highlighted in reverse video.

The value of full-text can be attributed to more than the convenience of having the whole story at your fingertips. While it is certainly pleasant to receive information immediately instead of having to wait for document delivery, there’s something even nicer about full-text databases.

There is no abstractor involved.

This translates into free access to all of the information that was in the article, whether or not a third party happened to consider it important. This allows you to search for named people with a greater chance of success, and to track events that may not have been considered very important at the time the article was indexed (but became so later). In short, you decide what you see.

Other on-line services offer full-text news as well, with items such as the following routinely available within a day of original publication:

0000720

SECTION: International news

STORY ID: Egypt

DATELINE: PARIS (UPI) January 08, 1983

TIME: 08:42PS CYCLE: bc

PRIORITY: Deferred

WORD COUNT: 0254

Senior Iraqi and Egyptian officials met in Paris Friday night, the first meeting be tween the two countries since Egypt was ostracized by the Arab world after signing a peace treaty with Israel in 1979.

Tareq Aziz, Iraqi deputy prime minister, and Boutros Ghali, Egyptian minister of state for foreign affairs, met at Ghali’s request at the home of Iraqi Ambassador Mohamad Al Maschatt, Iraqi officials confirmed today.

Ghali stopped in Paris en route to Nicaragua for a meeting of non-aligned countries.

Aziz told a news conference Friday that Iraq felt “one must take into consideration and encourage the positive attitudes adopted by (Egyptian) President Hosni Mubarak, otherwise the designs of Israel to isolate Egypt from the Arab world” will succeed.

Iraq became the fourth Arab country to officially mend fences with Egypt since Mubarak became president. Jordan, Morocco and Lebanon already have resumed ties with Cairo but have stopped short of restoring formal diplomatic relations.

All Arab states except Oman and Sudan severed diplomatic relations and recalled their ambassadors after the Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty.

Iraqi officials indicated Baghdad hopes to resume buying arms from Egypt and receiving other Egyptian aid for Iraq’s continuing war with Iran.

Using simple “free-text” searching techniques, you could retrieve this story by any combination of words you can think of, including:

“war” and “peace”

“Arab states”

“Oman” within 2 words of “Sudan”

“Mubarak” but not “Moscow”

“Egypt” and “diplomatic relations” and “news”

“fences” and “affairs”

any word beginning with “bag”

“January 8, 1983”

and so on. But let’s turn now to a more universally available class of

databases.

Bibliographic Databases

The information you are most likely to see as you begin using on-line services is not the complete text of the items that you turn up, but instead bibliographic citations to them (usually accompanied by abstracts). This is occasionally frustrating, of course, since you are probably looking for the “source” information and might thus view bibliographic citations as only an annoying intermediate step. They do, however, allow you to scan a substantial collection of articles and other documents without having to actually read each one to discover its main points.

The potential problem here is that the content of a bibliographic record in a database — with the exception of such “factual” items as the title, date, and so on — is determined by some anonymous abstractor who works for the database producer. While these abstracts are generally of high quality, their sophistication can vary widely from one file to another. Since much searching is done on the basis of terms that appear somewhere in the abstract (“find all articles that mention used computers”), you depend for your searching effectiveness upon the abstractors’ choices of wording. In the used computer case, for example, you might miss a perfectly-targeted article about the changing market for “used data-processing equipment” while spending good money to print out an abstract that reads, in part: “…BASIC is still the most commonly used computer language.” (This calls for a certain finesse in searching technique.)

Bibliographic citations vary widely in style from one database to another. The Magazine Index of over 370 popular publications only rarely includes abstracts, requiring that all subject searching be done on the basis of the title and some assigned “descriptors.” A 1981 article by this author, for example, appears in this database as:

Online information retrieval.

Roberts, Steven K.

Byte v6 p452(7) Dec 1981

CODEN: BYTEDJ

SIC CODE: 7374; 8231

DESCRIPTORS: information storage and retrieval systems-evaluation; Magazine Index (database)-usage; computer networks-usage; database management-technological innovations; Information Access Corp.-services; information services-innovations

You could only locate this by including the author name, the title, or at least one of the descriptor phrases in your search strategy. It is interesting to note that the database publisher, Information Access Corporation, saw fit to include themselves as one of the descriptors — even though they were never explicitly mentioned by name and others were! Ah, marketing.

The same article is referenced in other databases as well, and the comparison is interesting. In the Microcomputer Index, for example, it appears as follows:

Online information retrieval: promise and problems

Roberts. Steven

BYTE, Dec 1981 , v6 n12 p452-461

7 pages ISSN: 0360-5280

Languages: English

Document Type: Article

Geographic Location: United States

Describes how an information search is

done on the Dialog Information Service. Also includes some comments on the five prerequisites that were needed to develop the Dialog system and comments on future problems, in this field.

Descriptors: ‘Online Systems; “Online Information

Identifiers: Dialog Information Services Inc.

It would not be immediately obvious to a casual observer that these two database records refer to the same article. Further compounding the confusion, here’s the same thing in INSPEC:

ONLINE INFORMATION RETRIEVAL: PROMISE AND PROBLEMS

ROBERTS, S.K.

BYTE (USA) Vol.6, NO. 12 452-61

DEC. 1981

Coden: BYTEDJ

Treatment: GENERAL, REVIEW

Document Type: JOURNAL PAPER

Languages: ENGLISH

The on-line, storage capabilities described in the article seem to presage enormous changes in the library of the future. One can only assume that mass storage of all types will continue to grow cheaper as human time becomes more expensive; it follows that ever-better tools for information seekers will continue to develop.

Descriptors: INFORMATION RETRIEVAL SYSTEMS; INFORMATION SERVICES

Identifiers: INFORMATION RETRIEVAL; ONLINE; LIBRARY; FUTURE

Class Codes: C7210; C7250

A bit confusing, eh? The first is a nuts-and-bolts piece about some specific information storage and retrieval systems, the second tells how to perform a DIALOG search, and the third consists of philosophical commentary about future libraries. The authors, Steven K., Steven, and S.K. respectively, had to be quite versatile to say all that in one 7 or 9 page article (depending on which citation you believe)!

Of course, the article could be found in all three databases by searching for the term “online” — but so would hundreds of others. The point we are making is that while bibliographic references offer great flexibility, they are not guaranteed to reflect the content of the article in any predictable fashion. Since there is a level of interpretation between the original text and what appears on your terminal, you can never be absolutely certain that what you see is what you’ll get.

All that notwithstanding, however, bibliographic citations make it possible to access the masses of published information that continue to become available at a rate that has been estimated as high as 200,000,000 words per hour. We are still quite a few years away from having the full text of all material available on-line — even ignoring copyright and legal problems, the costs of data storage and transmission are prohibitive. It is therefore worthwhile to become comfortable with the form of a bibliographic citation and the kind of information it can yield.

Just the Facts” Databases

Our third major “class” of databases is the huge and diverse group commonly known as “non-bibliographic.” Since we have considered full-text databases to be a category all their own, this one consists of every kind of on line information except articles, books, conference papers, and the like.

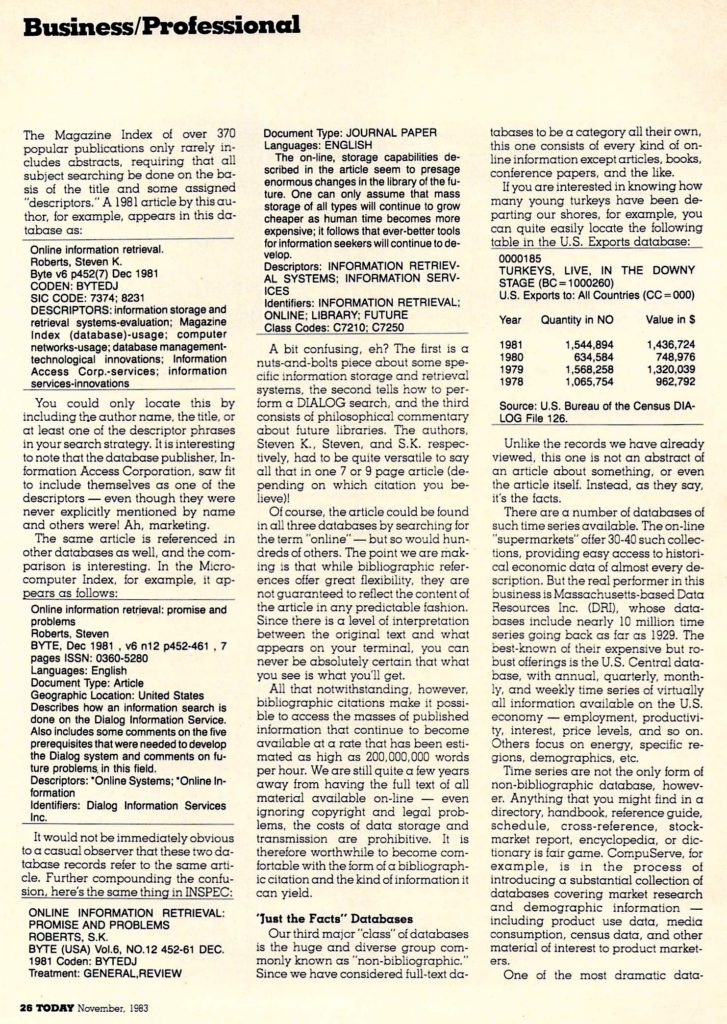

If you are interested in knowing how many young turkeys have been departing our shores, for example, you can quite easily locate the following table in the U.S. Exports database:

0000185

TURKEYS, LIVE, IN THE DOWNY STAGE (BC = 1000260)

U.S. Exports to: All Countries (CC = 000)

| Year | Quantity | Value $ |

| 1981 | 1,544,894 | 1,436,724 |

| 1980 | 634,584 | 748,976 |

| 1979 | 1,568,258 | 1,320,039 |

| 1978 | 1,065,754 | 962,792 |

Unlike the records we have already viewed, this one (table added in 2020 to be readable on the web) is not an abstract of an article about something, or even the article itself. Instead, as they say, it’s the facts.

There are a number of databases of such time series available. The on-line “supermarkets” offer 30-40 such collections, providing easy access to historical economic data of almost every description. But the real performer in this business is Massachusetts-based Data Resources Inc. (DRI), whose databases include nearly 10 million time series going back as far as 1929. The best-known of their expensive but robust offerings is the U.S. Central database, with annual, quarterly, monthly, and weekly time series of virtually all information available on the U.S. economy — employment, productivity, interest, price levels, and so on. Others focus on energy, specific regions, demographics, etc.

Time series are not the only form of non-bibliographic database, however. Anything that you might find in a directory, handbook, reference guide, schedule, cross-reference, stock-market report, encyclopedia, or dictionary is fair game. CompuServe, for example, is in the process of introducing a substantial collection of databases covering market research and demographic information — including product use data, media consumption, census data, and other material of interest to product marketers.

One of the most dramatic data-bases, in terms of overall awesomeness, is the Electronic Yellow Pages, available on DIALOG. This, in short, is a combination of all the Yellow Pages directories in the United States (some 4,800 in all), cross-indexed in a fashion that lets you find all the drywall contractors in Topeka or all the bookbinders in area code 612. You can also track individuals or companies (what ever happened to Dr. Parenteau?), produce zip-code sorted lists by SIC code, and so on. A typical record looks like this:

1396

3/a/139

D S DOG TRAINING

512 W HELM WAY

CASSELBERRY, FL 32707

TELEPHONE: 305-831-7096

COUNTY: SEMINOLE

SIC: 7393B (GUARD & PATROL SERVICES)

ADVERTISING CLASS: DISPLAY AD

CITY POPULATION: 4 (10,000-24,999)

THIS IS A(N) FIRM

Another impressive non-bibliographic database is Books in Print, corresponding to the printed directories from Bowker that occupy about two feet of shelf space. If you are trying to find a book by a given author, find the author of a given book, locate ordering information, or find all books in a given subject category during a certain range of dates, this index to the entire U.S. publishing industry’s output can be of help. If you find yourself interested in bicycle camping, for example, a quick search on the terms bicycl? and camp? yields the following:

Harsh-Weather Camping: How to Enjoy

Backpacking, Canoeing & Bicycling under Any Conditions

Curits, Sam

224p.

Arco 10/1983

Trade $14.95; pap. $7.95

ISBN: 0-668-05833-1; 0-668-05840-4 LCON: 83-007240

Status: Active entry

Illustrated

SUBJECT HEADINGS: CAMPING (00069772); CAMPING-OUTFITS, SUP PLIES, ETC.

(00571416)

PBIP SUBJECT HEADINGS: HEALTH AND PHYSICAL EDUCATION- RECREATION

(00001284)

Of course, it also yields a few others, including this one:

0235542 2280310XX

Theatre: Avec: Guernica, Le Labyrinthe,

Le Tricycle, Pique-Nique en Campagne. La Bicyclette du Condamne

Vol.2

221 p.

French & Eur 1968 Trade $9.95

ISBN: 0-686-54464-1 Status: Active entry

The use of a $65/hour database (plus another $8/hour for communications) may seem absurd in comparison to a couple hundred dollars worth of books that you could explore to your heart’s content at no additional cost. But the printed volumes are constantly being updated — and like dictionaries, you have to know what you are looking for to find what you are looking for. In the on-line version, you can search on any combination of terms and even generate an output that is sorted by title, author, publication year, Library of Congress number, or ISBN.

Another directory of interest is one known as the Encyclopedia of Associations. If you wanted to find more information about those exports of young turkeys, for example, you could log on to this database, ask for associations that have something to do with “turkey” and “market,” and be rewarded with the name of an industry association that could probably tell you more than you ever wanted to know about the subject:

NATIONAL TURKEY FEDERATION

(Poultry) (NTF)

Reston International Center, 11800 Sunrise Valley Dr., Suite 302, Reston, VA 22091

(703) 860-0120

G.L. Walts Exec. VPres.

Founded: 1939. Members: 2500. Staff: 5

State Groups: 48. Turkey growers, hatcherymen, egg producers, processors and marketers. Works to increase consumption of turkey; promotes favorable legislation; collects and distributes news material, marketing information, and other data about the turkey industry; promotes turkey research, makes information available on turkey breeding, raising and marketing. Publications; (1) Newsletter, monthly; (2) Promotional Brochure, annual. Convention/Meeting: annual – always January. 1983 Jan. 12-14, New Orleans, LA.

Section Heading Codes: Agricultural Organizations and Commodity Exchanges _1Q2J

This database can be of tremendous value (much more than the printed directory of the same name) in locating groups of almost any conceivable common interest for marketing, professional, or personal reasons. You’ll find, among others, the National Lubricating Grease Institute, the Association for Mexican Cave Studies, the Fantasy Association, and the International Association of Professional Bureaucrats (whose motto is, “when in doubt, mumble”).

If you are interested in doing business with the federal government, you already know about Commerce Business Daily, issued by the Department of Commerce to announce products and services wanted or offered by the government. If you have ever tried keeping track of everything in there with the hope of landing a government contract, you’ll probably agree that it almost calls for a full-time person— especially if you include the associated paperwork of maintaining a presence on bid lists.

The Commerce Business Daily database will help change all that. Updated — you guessed it — daily, it gives you instant access to the full content of the printed publication, with the added benefit of requiring you to look only at the portions that are directly associated with your interests. If you perform biochemical analysis of sex hormones, for example, you may be interested in this item:

0208915

CONDUCT BIOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS Sole source negotiations to be conducted with Texas A&M Research Foundation to conduct additional biochemical analysis of sex hormones from turtles captured at Cape Canaveral and Indian River, FL. See note 46.

Sponsor: U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Duval Building, 9450 Koger Blvd., St. Petersburg, FL 33702, Jean B. Martin, Contract Specialist, Tel 813-893-3788 Subfile: PSE .(U.S. GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENTS, SERVICES)

Section Heading: A Experimental, Developmental, Test and Research Work CBD Date: FEBRUARY 16, 1983

The file is divided into categories (RFPs, Solicitations, Surplus Property Sales, Contract Awards, etc.) that allow you to restrict your search as necessary to minimize the amount of extraneous information retrieved. Thiscan reduce your on-line time to a few minutes and make this approach much more cost-effective than working with the printed publication. There are other databases that are useful in the attempt to find a market. If you yearn to sell Frisbees in Australia, a quick search in the Trade Opportunities database would yield the following:

206842 DATE: 820526 AUSTRALIA EXCLUS. AGENCY/DISTRIB.

Frisbees for advertising & promotional use. AMF function primarily as marketing consultants who also import & nationally distribute range of giftwares & advertising premiums. Firm seeking exclusive agency or distributorship for promotional products called “Flippy Flyers”. These are nylon flying discs with weighted edge, similar to Frisbees, & used in advertising.

Product literature & prices requested. REPLY TO —

Mr. Garfield Wells, Mng. Dir. Australasian Market Force PTY. LTD. (AMF)

P.O. Box 4

Milsons Point, NSW 2061, Australia

CABLE: MARFORCE SYDNEY

TEL: (02)436-2188

Please send copy your response to — American Consulate General

Sydney, Australia

T&G Tower, 36 FL, Hyde Park Sq

APO San Francisco 96209

PRODUCTS (SIC): 9950018

BUSINESS CODES: A (BN = AGENT; I (BN = IMPORTER); D (BN = DISTRIBUTOR);

COUNTRY CODE: 602

TYPE OF OPPORTUNITY CODE: 114 NOTICE NUMBER: 332441

It becomes clear that this could go on and on. The economics of doing business dictate, inflexibly, that human time is the critical resource. Spending $10 to get a computer 2,000 miles away to tell you something that is printed in a directory on your desk might actually make sense — in fact, when you consider the combined effects of timeliness, scope, and searching flexibility, it sounds like a pretty good idea.

Let’s look at one final non-bibliographic example — this time from the realm of chemistry.

One of the largest database producers in the world is Chemical Abstracts Service of Columbus, Ohio. In addition to the abstracting and bibliographic service that the name implies, the firm produces databases of millions of substances indexed by molecular structure, names, registry numbers, and so on. If you were researching ergot derivatives and their synthetic cousins, for example, you might locate this typical entry in the Chemsis file of “singly indexed substances”:

CAS REGISTRY NUMBER: 81019-63-8

FORMULA: C21H29N302

CA NAME(S):

HP = Ergoline-8-carboxamide (9CI),

SB = N,N-diethyl-2-methoxy-6-methyl-,

ST = (8.beta.)-

HP = lndolo(4,3-fg)quinoline (9CI),

NM = ergoline-8-carboxamide deriv.

SYNONYMS: 2-Methoxy-9,10-dihydro- N,N-diethyllysergamide; 2-Methoxydihvdro-LSD

With that bit of light reading, we come to the end of this introduction to the three broad classes of databases. Let us now consider the problem of fitting these resources to your needs.

Your Information Requirements

No single person, with the possible exception of a professional database

intermediary, could conceivably need all of the available on-line services. They are as diverse as human knowledge itself.

One of the first decisions you must make as you begin delving into all this is which databases will be useful enough to justify the expenditure of your time and money. The answer will gradually emerge as you survey the available options, but the issue can be more than a little confusing at first. Consider the following advertising claims made by various information vendors:

Predicasts: “PTS — unequalled databank with computerized speed — is the most complete business information service available to companies involved in making or marketing a product or service.”

PAIS: “. . . the database covers just about every subject that has to do with

people interacting with other people — and with their institutions and businesses.”

Dow Jones: “It’s a convenient, easy-to-use service that can help you or your company make money and manage your investments better. What’s more, it provides just the information you want, at your fingertips.”

FIND/SVP: “We are your Total Busi ness Information Resource.”

DIALOG: “Only the DIALOG Service provides such comprehensive coverage of information on virtually any subject . . . DIALOG is the most powerful retrieval system in the industry.”

SDC: “SDC’s exclusive features on the ORBIT Information Retrieval System assure the fastest, most flexible search of the widest range of data bases…”

All of these claims have considerable justification: the information resources being advertised are indeed as valuable as their producers say. But from the standpoint of a new user, this is a bit confusing; you must somehow extract from the deluge of marketing copy a subset of the world’s databases that are relevant to your operation.

This problem has begun to receive attention in the on-line industry press. As with any new technology, there is a profusion of unfamiliar terms with meanings that have yet to be universally agreed upon; even the word “database” suffers from a surfeit of valid interpretations.

Viewing on-line information services in the light of your own needs can start with this article — I have attempted to segment the available databases into three major categories. But this is only a small beginning. Your next step should be the acquisition of literature from all the vendors of interest. Along with this, it is recommended that you sign on with one of the database “supermarkets” and get in line for their introductory seminar— typically a day and a half of intensive exposure for $100-200. This approach will give you access to a wide range of databases, even though you may ultimately settle upon only a half-dozen or so for regular use.

It is important to note at this point that you have another option. It is not at all necessary for you — the ultimate user of information — to become conversant in the details of on-line searching. As you may have already guessed, there is a fair amount of detailed technique involved in learning to search effectively, and not everybody has the time, inclination, or analytical skill to carry that off. It is comparable to any other kind of computer use: You certainly don’t have to be come a programmer in order to make effective use of a personal computer system. If you did, microcomputers would still be primarily marketed to hobbyists, as they were in the mid-1970s.

You may relegate the actual searching tasks to an intermediary — handing him or her a request for information and receiving, hours or days later, a thorough answer replete with executive summary. This is easier, although more expensive and considerably less satisfying than doing it yourself.

So let’s consider a typical applications area (assuming, now, that you are in the mood to do your own on-line work) and consider the approaches you might take to equip yourself with appropriate database resources.

Company Information

There are a number of good reasons for wanting to keep track of goings-on in other companies, and this universal desire is responsible for a significant percentage of business database use. Consider some of the motivations you might have for wanting to research details about other companies:

- Merger and acquisition research

- Credit investigations

- Investment opportunities

- Finding venture capital sources

- Market research and analysis

- Legal information for precedent or litigation

- General corporate planning

- Personnel — finding people or jobs

- Mailing list preparation

- Company investigations

and so on. No business can healthily operate in an information vacuum.

Should you decide that you need the ability to perform such searches, you will discover a surprisingly large number of sources that will be of value. Let’s look at a few . . .

Disclosure II. One of the more visible databases of company information, this file contains significant extracts of reports filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) by over 9,000 publicly-held companies. These are primarly 10K reports, and they include income statements, balance sheets, names of key personnel (with their ages and salaries), segment data, five-year summaries, accounting methods, subsidiaries, filing dates, and recent management discussion. The database is heavily cross-indexed, and can provide immediate, detailed information for $6-12 per company. It is accessible through DIALOG, Dow Jones, and Mead Data Central.

Dow Jones News/Retrieval Service. This system provides a number of company investigation tools in addition to Disclosure II. One that is of particular value is knows as Media General — updated weekly, this database includes earnings, dividends, trading volume, ratios and so on for 3,200 publicly-held companies. In addition, it provides composite information on 180 industries. A typical report costs $1.00.

Other files of interest on Dow Jones include historical and current market quotes, full-text transcripts of Wall Street Week, and a corporate earnings estimator for 2,400 companies.

CompuServe. Offering services at very low Columbus-based system provides securities information, the Value Line database, and other specific data. It also hosts “Business Wire” (a wire service of news releases) and numerous other compilations of material that can be of value in a company investigation. On-line time for most CompuServe services costs $22.50/hour, or $5/hour during evenings and weekends.

Standard & Poor’s News. More current but less complete than Disclosure II’s summaries, this database covers over 9,000 public companies and provides not only standard financial information, but interim statements as well. Searches run anywhere from $1 to $10.

Economic Information Systems files. These comprehensive files — one for industrial plants and the other for non-manufacturing establishments, provide information on firms that account for nearly 90 percent of the U.S. economy. In the industrial database, for example, companies having over 20 employees and annual sales of over .5 million are included — with information on parent companies and subsidiaries, market share, products, sales, employment level, address, and so on. This database, on DIALOG, runs $90/hour plus an incremental charge for each record displayed — yielding an average search cost of $5-8.

Dun & Bradstreet Business Information File. This database overlaps the others quite a bit, but offers reports on subsidiaries of public companies that are difficult to find elsewhere. A typical report is $10.

Spectrum. This database, the most expensive of the category, will cost you about $100 per full report. As such, it is seldom used, but it does possess the distinct advantage of providing complete ownership profiles of public companies.

Electronic Yellow Pages. Although it offers no significant financial data, EYP is still an excellent value in company investigation because of its scope. It has no cutoff for assets or number of employees and includes over 10 million listings. This is a good way to find all companies operating under a given name, or all those listed under a specified SIC code in a particular geographical area. $60 per hour on DIALOG.

PTS PROMT. There are a number of bibliographic resources that can be of considerable utility in tracking the goings-on of a particular company. Including abstracts from about 800 journals, studies, and prospecti, PROMT allows searches on the basis of company names, trade names, events, dates, product codes, and so on.

Other bibliographic databases. There is no single bibliographic database that can stand fully alone as a source of company research information. There are dozens of news databases (UPI, New York Times Information Bank, National Newspaper Index, Dow Jones News Retrieval, etc.) and even more industry-specific databases (Coffeeline, INSPEC, Pollution Abstracts, Weldasearch, Metadex, Insurance Abstracts, and so on) that should be used to track events in the field of interest. The diversity of these and the need to use more than one or two form the basis for my suggestion that you turn first to a “supermarket” vendor.

Other files. In addition to all the above — even the last “catch-all” category— there are numerous databases which, in certain circumstances, can help considerably in a company investigation project. It is possible with the Adtrack database, for example, to see who is buying ad space of 1/4 page or more in about 150 major consumer magazines, and the Career Placement Registry can reveal the names of people at a given firm who are getting restless. Commerce Business Daily lists those companies that have successfully bid on government projects, and corporate sources are listed in the U.S. Patent files and the Conference Papers Index. The Congressional Information Service database can be searched for the corporate affiliations of witnesses. The list goes on and on.

As you can see, the process of researching company information is a complex one for which there are abundant on-line resources. The same can be said of engineering, general business information, legal work, life sciences research, news, and virtually every other major endeavor. The message here is that the claims made by advertisers in the information industry should be taken with every bit as much sodium chloride as those of other disciplines: there is simply no single source that can represent a “one-stop shopping” environment for anyone with complex requirements.

Of course, not everybody’s information needs are as complex as all that. Perhaps you are an attorney specializing in patents and intellectual property in the microcomputer field — then you could probably do quite well with a few patent databases (CLAIMS, DERWENT, and PERGAMON), one on general law (LEXIS), another on patent law (PATLAW), one on trademarks (COMPU-MARK), a few on the technology itself (INSPEC, COMPENDEX, Microcomputer Index, International Software Database, etc.) the Congressional Record, Dissertation Abstracts, and a scattering of general files such as MARC, Magazine Index, Books in Print, and NTIS.

Summary

As the foregoing suggests, there is more to using on-line services than buying a terminal and signing a contract with a vendor. You must become familiar (and then stay that way) with a number of different databases and systems — few of which offer exactly the same command formats. It can be a little overwhelming.

I have already mentioned that you have the option of relegating all your online searching activity to your company librarian or other intermediary. But before concluding that this is a necessary approach, give searching a try. You may become hooked. Besides, nobody can ever know your own applications as well as you do, so why suffer through the process of explaining your needs to someone else? A truly sophisticated intermediary can “draw you out” and discover more about your requirements than you probably knew yourself — but such competence is rare and quite expensive in this young industry.

Perhaps the best way to resolve this trade-off is for us to explore, next month, the adventures of a small company coming to grips with the relentless need for information. It’s a story of tough corporate decisions, of battles between engineering and management, of mighty egos, of the “not invented here syndrome,” and of missed opportunity. It’s a story of doing business in a changing world, with traditionally successful methods leading earnest managers smugly toward disaster. But it’s a story of hope, if we can only get the company to listen to reason . . .

Steven K. Roberts is a free-lance writer from Columbus. Research for this article took place during his recent participation in a book project: INCs Databasics, Garland Publishing. 1984. Roberts’ CompuServe User ID is 70007,362.

You must be logged in to post a comment.