Rolling into Dataspace

Computing Across America, Chapter 6

by Steven K. Roberts

October 4, 1983

I would live all my life in nonchalance and insouciance

Were it not for making a living, which is rather a nouciance.

—Ogden Nash

My first sensation after the initial shock was freedom — a dizzying and unfamiliar freedom. I stood quietly as the festivities evaporated around me, realizing that I could do whatever the hell I pleased and that nobody would care.

Free! I had broken the chains that bound me to my desk, then sold the desk and torn down the walls. They were falling away even as I stood there in Eagle Creek Park; they were crumbling to rubble so fast that I experienced a sort of vertigo. My familiar walls were gone.

I struggled to grasp the boundaries of the new space I had created for myself. My world was no longer limited by the constraints of time and distance — nor even responsibility. That thought was both delicious and unsettling, and I suddenly realized, alone in this unfamiliar city, that I was as close to “home” as I would be for a long time.

I rode slowly away, thinking about the article that had to be in Boston by 9:00 the next morning. A comprehensive overview of artificial intelligence research, tailored to an engineering-management audience? Right. I shook my head, cruising slowly, a high-tech Sunday driver drifting through the park. A trade journal article? I didn’t even know where I’d spend the night, much less where I’d set up a place to work.

I stopped by the side of the road to ponder the problem, fishing a rumpled napkin out of my pocket to check the crude map someone had drawn for me. There was more than one level on which I was disoriented. I was staring at the smudged lines in growing irritation when a trim man on a racing bicycle glided to a silent stop beside me.

“Lost?” He chuckled at the napkin.

“Well, sort of…”

“You had lunch yesterday at the Bob Evans down by the airport, didn’t you?” He gestured vaguely over his shoulder.

“Uh, yes, how’d you know that?” I struggled to recall his face.

He grinned and extended his hand. “I’m Harold. My daughter Kelly works there.” I recalled the pretty blonde hostess. It’s hard to slip around incognito on an eight-foot-long recumbent.

Within a few hours I had commandeered Harold’s dining room table in the suburb of Clermont and, in the fine tradition of procrastinators everywhere, attacked the article assignment in a frenzy of last-minute passion.

After midnight. Gently, furtively, I removed my hosts’ telephone from their kitchen wall and plugged in the modular jack. I felt like someone in a Mission Impossible episode, hunched over a miniature computer system in a dark midwestern house, the family asleep and unaware of the data transmissions originating beside the Cuisinart. The article winged its way through the ether and came to rest on the spinning platters of a CompuServe disk drive in Columbus. In the morning, my editor at Mini-Micro Systems would sign on and transfer it to a Boston typesetting system, while Kacy would do likewise to make a copy for our files. Ain’t technology wonderful?

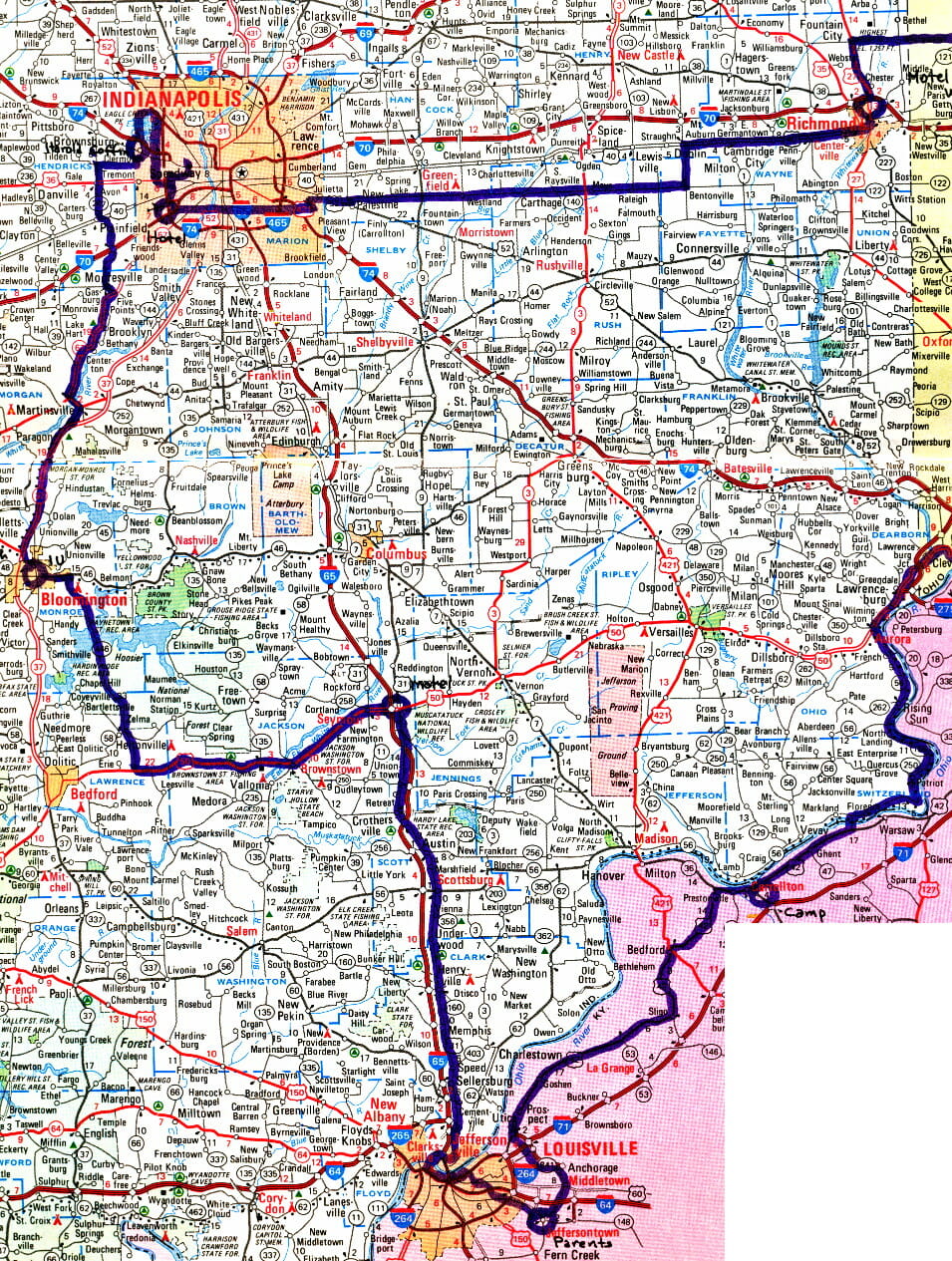

And then: the road. It felt like a beginning as I pedaled west out of Clermont and turned south to begin the headwind death march to Bloomington. The wind blew from the southwest with such force that I had to struggle in my almost-granny gear to progress on level ground. The minor hills were grueling from my out-of-shape perspective of the time, and traffic was unsympathetic. A jovial bald druggist in Plainfield sold me a knee support, and a drunk in Martinsburg told me I had to be outta my mind.

I pushed closer to Bloomington, and soon the college-town signs appeared: youth, beauty, posters, graffiti, armloads of books. That’s when the fun began…

“Oh my God!” squealed the bevy of students in a forced Midwestern dialect of Val-speak. “Look at that totally awesome bike!” I obediently stopped to allow closer examination. The usual questions were suddenly a pleasure to answer, and trying not to be too obvious, I hinted that I had not yet decided where to stay. No response, but the evening was yet young.

I explained the bike dozens of times. I glided silently along sidewalks between dark campus buildings, flashed my lights at other cyclists, and discovered the timeless appeal of the college town. At last, chilly and tired, I was taken in by two students who fixed me tea and pulled a classic all-nighter of test-cramming while I drifted into slumber.

Bloomington held me for a couple of days. The skies remained grey, and an exhausted torpor gripped me. Lazy and unmotivated, I hauled the bike to the top floor of a dingy building and crashed hard. Robby’s prediction had been true: everything hurt, and while my hostess had the rare opportunity to hear Kurt Vonnegut speak on campus, I slept. When I finally marshaled the energy to write, I spilled candle wax on the computer and gave up.

But about a hundred miles south in Louisville, my parents were nervously awaiting my visit — skeptical about their adopted child’s latest aberration. At first my mother had tried to dissuade me by sending newspaper clippings of people injured or robbed while traveling; when manipulation failed to have the desired effect, she tried reason. I called from Bloomington and they heard the weariness in my voice, evasion of their questions about the bad knee. It was time for a reassuring visit.

A poignant sense of the familiar struck as I crossed the Ohio River after a two-day ride to Louisville. This was my old home town, and the memories penetrating my exhaustion dwarfed the immediate problems of traffic and broken glass. If I would feel any lingering sense of home at all, it would be here.

I made a hesitant pilgrimage to the Crescent Hill house I had owned for three years. It was an eighty-year-old, thirteen-room Victorian with stained glass and a porch swing — I stopped in my old parking spot and gazed across my lawn at countless signs of another family. Carefully crafted micro-based industrial-control systems had been born in the second-floor laboratory… my daughter had been conceived down the hall.

With a lump in my throat and an ache in my body I continued toward my parents.

Watching irrationally for familiar faces, I fought rush-hour traffic on roads I’ve known for years: Frankfort, Cannons, Taylorsville. I eyed with resentment the new gas stations, my quaint old Louisville gradually becoming the same place as everyplace else. I had played around a streamside weeping willow where now sprawled a condo complex; I had taken “bike hikes” along shady country roads that were now four-lane strips of muffler shops and franchised fast foods. The glimpses of buried character, stubborn hold-outs who hadn’t sold, were only making it worse.

But there it was, inside the old white board fence in Jeffersontown: the trees bigger, stream flowing brown, mailbox freshly painted, the same cats or their descendants awaiting handouts. The greenhouse, the weathered barn, the ’63 Comet still well-maintained in the driveway — it was all there.

I parked the bike and stood unsteadily. The back door opened, and there was my mother — older than I remembered — regarding me with that classic maternal mixture of love, concern, and accusation. “My God! You must be starving!”

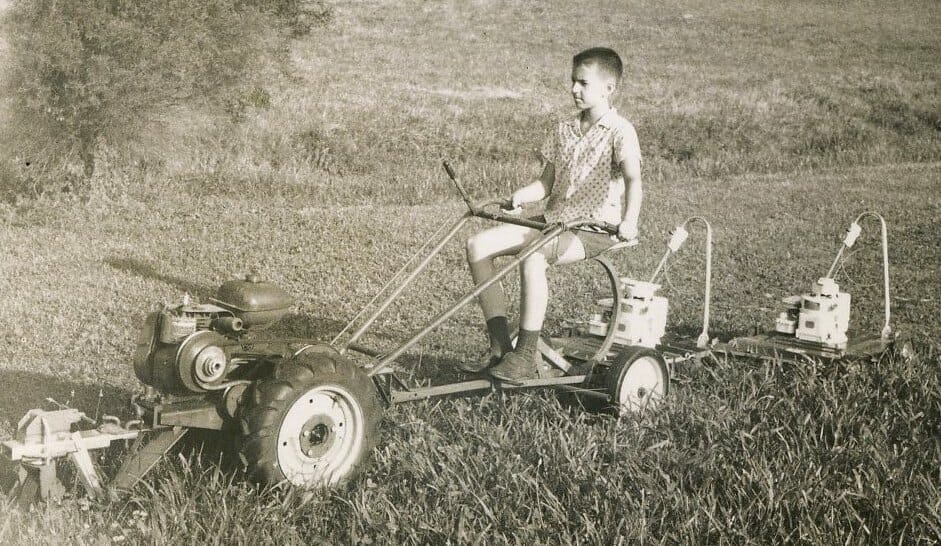

My father emerged and ran the appraising eye of a retired engineer over the bike, questioning me about spare chain links and tools. I toured the orchids and was brought up to date on barely remembered neighbors. Nothing had changed — I was still their kid at 31, and I set to work trying to reassure them about my new life.

They questioned my motives, reminded me of past aborted ventures, opened the painful subject of money, and commented on my responsibility to Amy — the offspring of my brief marriage 3 years before. I tried to explain, but they could see only a doomed rerun of my teenage wanderings. I gave up and spent the rest of the visit online with new friends somewhere out in the vapors. “What the hell’s he doing in there?” I heard my mother ask, as I was hunkered down in the den, plugged into the phone line. More emotional ties were fading — Columbus had never really felt like home, and now neither did Louisville.

In the absence of tangible roots, I was free to roll down the highway. Mom packed a lunch and Dad checked my tires; I installed a new derailleur and performed the pre-flight check. Impressed by the scope of the undertaking but convinced I’d never grow up, my parents watched with ill-concealed nervousness as I piloted the Winnebiko down their driveway and out into the vast, vast world of unknowns.

The roads leading away from Louisville boosted my spirits — like the ones that had carried me out of Columbus, they were tinged with familiarity. Knowing the old, I could better sense the new, and the scenic miles of US42 delighted me.

But after a brief hug-stop that rekindled a fond memory of the seventies, something started to worry me.

Would the romance of this journey be just a succession of fleeting encounters? As I pedaled the curvy highway I imagined them: flashes at random intervals along the convoluted red line of my atlas. How could a peripatetic life provide enough warmth to keep me from going mad with only “beginnings” to sustain me?

I would be just passing through… all the time.

I sighed at the thought as I pedaled northeast, wondering if my glib claim of “beating the freedom vs security trade-off” involved having neither instead of both.

That night, halfway between Louisville and Cincinnati, I sat in my open tent while the Sony pumped lush jazz into my head, the candle flickering perfectly with multisensory neural synchronization. One of the purposes of this shakedown was to shift my life into full-time nomadness, but feeling that actually happen was more complex than expected. I zipped up the Domicile, gazed intently at the seams, and realized that I was just getting to know my new home.

But I could no longer ignore the emotional cloud that darkened the horizon… for the next day I would see Amy.

My three-year-old’s face aglow with love and humor couldn’t darken a firefly, much less a whole horizon. But even though we had been living 100 miles apart and only rarely crossed paths, her existence symbolized the meta-level of everything I was leaving behind. That biological clock is persistent.

It was into this that I was about to pedal.

On a day bright with autumn sun and imbued with the smells of tobacco country, I rode the Indiana side of the Ohio River to Cincinnati, stopping in the town of Patriot for lunch.

Uh-oh. The hoots and guffaws began the moment I pulled into the parking lot. I glanced uneasily across the street to the source of the noise and saw two teenagers jump into a car — the jacked-up, noisy kind of car associated with “youth” of the late-fifties. They screeched across the street in a smoky flash of Cragar and leapt out, chins jutting with insouciant aggression, hard-muscled arms at the ready.

“What’s this solar shit?” asked one, with a contemptuous gesture to my gleaming Solarex panels.

“Well, as a matter of fact,” I answered with a theatrically easy grin, “that runs the computer. Also the lights, stereo, CB, and security system.” I placed subtle emphasis on the word security.

“Yeah?”

“Yep. I’m crossing the United States on this machine, writing a book and doing TV shows. Haven’t you seen me on the news?”

“Whoa, you’re on TV with this thing? Where’s the motor?”

I slapped my thighs. “I’m standin’ on it, man! And I’m outta gas — anybody serve a decent lunch in this town?”

They both laughed. “Nobody around here, man. Unless you like microwave sandwiches.” The situation was totally defused, and they gazed at my bike in awe. I explained how it works, and even let one of them sit on it.

There was a lesson here. It was never stated or brought to the surface, but I had just been tested, challenged, and invited to defend myself. It would happen again. But with eye contact, I touched the human parts below the veneer of teenage machismo; I shared something of myself and eased them into doing the same.

The scary ones are those who won’t meet my gaze. If I can’t look someone in the eye and quickly evolve from harrassable stranger to fellow human, I’m in trouble.

I would wear no sunglasses on this journey.

After a boring prefab sandwich nuked to number 3 on the dial, I pressed on into hilly Cincinnati. A high-traffic night ride landed me in Kay’s driveway.

I heard a squeal, and the curtains fell shut across the triangle of light where Amy had been watching, watching, patiently watching. The door opened and she ran down the concrete steps, hair flying, arms outstretched, the spark in her eyes very much a part of me. “You drive me nuts, Daddy!” she cried, and bounded into my arms.

A tear — mine — moistened her cheek. I blinked and looked up at Kay silhouetted in the doorway. It would not be an easy weekend.

You must be logged in to post a comment.