The First 200 Miles

Computing Across America, Chapter 5

by Steven K. Roberts

October 1, 1983

Are yew with NASA?

— Ohio farmer

Passionately consuming a mug of iced root beer, I sat with Walt and Robby in a Mechanicsburg cafe. It was our first break. Outside, on a hot and sloping small-town main street, stood the bikes — mine the focal point of a small crowd. Back then, gawkers were still a novelty, and I watched in unconcealed fascination as they studied the machine and speculated about the solar panels. We were sweating and tired, and called for another round.

Robby stared out at my bike for a moment, then chuckled. “I’ve got three suggestions for you, Steve, if you don’t mind advice from an old codger.”

I had never thought of this energetic 65-year-old as a codger, but I grinned back at him. “OK, gramps, shoot.”

“First, take it easy out there until you warm up. I know you’re tempted to set some kind of speed record, but remember that the worst pain will come on the second or third day.”

I nodded, already feeling twinges in my right knee and pervasive muscle ache.

“Second, don’t let anybody nicknamed ‘Moose’ ride your bike. And third — never turn onto a road with ‘Mount’ or ‘Hill’ in its name.”

“Yeah, I reckon I’ll have a profound new respect for gravity before long.”

Robby nodded sagely. “You could use it. There are people who drill holes in their toothbrush handles to knock off a few grams, you know.”

I shrugged. “If it gets bad I’ll tear the tags off my teabags. But so far it seems manageable.”

Walt broke in with a laugh. “Yeah, and you’re in western Ohio, too. Ever think that it might get a little harder in the mountains?”

“I’ll have a taste of it soon enough. There should be some pretty good hills south of Bloomington, and I’ll be — “

“That’s not the Rockies,” Robby said. “You know how to pack for a bicycle trip? You make a big pile of all the stuff you absolutely need — then eliminate half of it and take the rest.”

I had to laugh.

“You’ll find out.”

“Hey, Roberts, you got any idea where we’re gonna pitch camp tonight?” Walt and I were now the only ones left, Robby having darted ahead to the Indianapolis races in a friend’s van. We had gone about sixty miles.

“Nope.” I stretched forward to study the map in its clear plastic case behind the fairing, and almost rode into the ditch — that little maneuver would take a few days to perfect. “The next real town is Troy, but it looks like about thirty miles yet.”

“We don’t have that much light left.”

“Yeah, not to mention this knee. I think we oughta start watching for a campsite. Any campsite.”

We were both exhausted. Two nights before, we had worked together until dawn on the bike electronics, his wife long since in bed, the stereo low. Walt had been hunched over his basement workbench, probing the still-erratic pulse of control circuitry; I sat tangled on the floor with a soldering iron in my hand, staring at a smudged schematic. This is the sort of thing that begins as a party and ends as agony.

And now we were westbound on farm roads: a long weekend for him, a new life for me. The country was hilly in places, and all day I had savored each novel twist in the land, whooped at every county line, and called out the odometer reading at ten-mile intervals as if it were some kind of score.

A new life. With every mile, I was a light-year further from the stagnation of the past. Counties drifted by like galaxies; the bike was a frail spaceship on a voyage of discovery.

But despite the thrill of the journey, problems were surfacing. We were tired and hungry. The sun was setting. And although I hated to acknowledge it, there was danger of engine failure: my right knee was slowly getting worse. I pushed hard with my left leg to let the other relax, but the swollen joint scraped as if filled with sand. With every stroke — some 350 to 400 per mile — my normally placid countenance hardened into a tighter grimace.

We arrived at sunset in the sleepy town of Terre Haute and walked into an understocked grocery. There were three short aisles, a fat woman loading up on Wonder bread, two kids buying candy, and a sullen teenager eyeing my bike and sucking furtively on a Marlboro. I shopped while Walt queried the locals about campgrounds.

The closest one was seventeen miles away. Two miles down the road, I knew I couldn’t make it. It was the knee: I was on the verge of crying out in pain and anger, betrayed by my own goddamn body. Biting my lip and cursing, I labored up a hill and stopped in front of a farmhouse.

Some little kids with healthy knees came bounding out of the front door, followed more slowly by two pretty women.

“Wow! Cool bike!” cried a youngster, as his sister stood shyly by the gate watching wide-eyed. “How fast does it go?”

“Not very fast at the moment,” I said with a forced laugh, “I’m wiped. We just rode from Columbus.

The kid’s face became the very image of awe. “On that?”

“Sure!” I glanced down at the display. “It’s only 69.9 miles.”

“Gawwwd! Mom! Check it out! He rode all the way from Columbus on that bike!” In Thackery, Columbus is considered an exotic and distant city. Mom smiled, guarded but friendly.

“We’re looking for a place to camp for the night,” I said with no further preliminaries. I had my eye on the back yard and was already fantasizing about a shower, perhaps an invitation to sleep on the couch. I smiled at her, and demonstrated the steering for the kid. “We were going to try for Kiser Lake tonight, but I’m having trouble with my right knee. I think it’s time to stop.”

She pointed down the hill we had just climbed. “Well now, we own that field down there ‘round the bend, on the left. I guess you can camp out there if you want. There are some stickerbushes an’ all, but it ain’t too bad.” She looked uncertain — I decided not to suggest the yard. Or the couch.

We thanked her and coasted back down to the ragged sloping field, densely overgrown with thorns and poison ivy. We thrashed around in the advancing dark with our flashlights, Walt muttering, me moaning; mosquitos whining, cattle lowing. These sounds were punctuated by the steady barking of a dog who stood on the edge of the field in the obvious conviction that he was holding us at bay.

“Jesus.” Walt was not impressed.

“Well, hey, it’s a place to camp.”

“Yeah, right.”

“How about over here?”

“Oh, man, I don’t wanna spend all night slidin’ down the goddamn hill in my sleeping bag!”

“Aw, it’s not that bad. Besides, it’s the only option other than the top of that hill — and I’m in no condition to drag my bike up there.”

“Yeah, OK, what the hell. Let’s haul our junk over here. But tomorrow night we stay in a motel.”

I agreed and started hobbling through waist-high weeds and ankle-high thorns with load after load, wrestling the bike through the ditch and over rusty barbed wire. I was tired, hungry, and whimpering with every step. It seemed that this would be it — that I’d limp to a phone the next morning and call Frank to come pick me up. It was over; I could feel it in every searing stab from the useless joint. “The knee is standalone proof of the fallibility of God,” I joked. “It’s a worthless design.”

“Yeah, it’s a lousy piece of engineering alright — probably cranked out at 4:30 on a Friday afternoon.”

But it wasn’t funny. I had just spent six months getting ready for this moment; I had frightened my parents, spent all my money, seduced the media, installed an office in the Branstetters’ home, and tied up Frank’s time. I had told all my friends and published rhapsodic magazine articles about “breaking the chains.” And now, after a mere seventy miles, my knee was failing as the world looked on with a smirk. I imagined slinking back to Columbus in the burning shame of failure, calling my parents and listening to them say “I told you so.” Elisse would express concern for my pain, hiding secret delight. And I’d ride the bike on Sunday breakfast rides with the local cycling club, telling everybody about the solar panels and how I would someday travel the world with my portable computer.

Shit.

In darkness and the confusion of unfamiliar gear, we pitched our tents. My Sierra Designs Domicile with shock-corded poles and clips rose easily; Walt cursed as he tried to keep the poles of his borrowed shelter together long enough to slide them through wrinkled fabric sleeves. I got everything more or less in order and limped up to the house to beg a bag of water.

And so it came to be dinnertime. Walt relaxed and nibbled cheese and salami from home, watching me with barely concealed disdain. “Man, I can’t believe you’re trying to cook something!”

“You don’t want any?”

“Hell, I’ll eat it, but I still think you’re crazy.” He shook his head as I shoved sticks under the stove to keep it from falling over on the hillside; he looked nervous as I squirted gasoline in the priming bowl and struck a match. With a whoosh the stove ignited.

“God damn!” he cried, recoiling in the sudden blaze. “That sucker’s a Molotov cocktail!” The trees around us danced in flickering shadows as my fire pushed back the night — then I gave the valve a twist and the wild yellow flare was replaced by a controlled blue flame that settled within seconds to a smooth roar. “You’re gonna kill yourself with that Swedish firebomb someday,” he predicted, watching warily from a safe distance.

“Dinner” was a dismal mixture of canned beans, canned chili, canned corn, and some kind of stringy cheese. Cayenne pepper didn’t help. We ate in grim silence, leaving the pan half full of the stuff — already forming a cracked brown crust on its muddy surface.

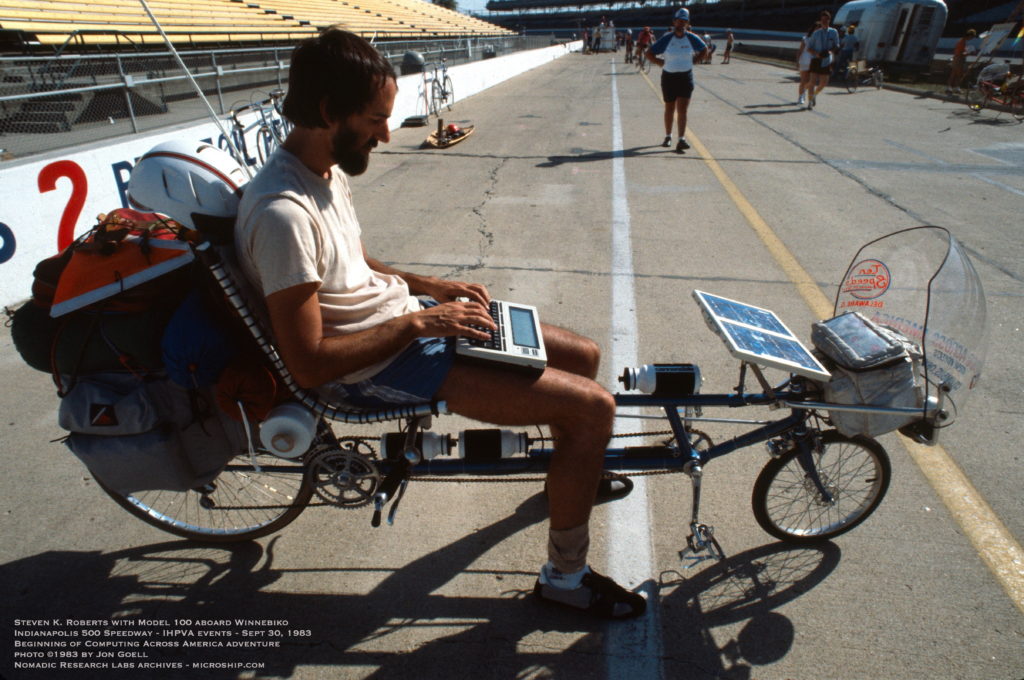

Alone in my Domicile, I typed a story by candlelight on the Model 100. I tried to write with enthusiasm — to make it all better with words. (I mentioned the knee, then lied: “Other than that, though, things are idyllic”) But despair hung in the close air of my tent like the smell of the day’s sweat; doubts nagged like the mosquitos.

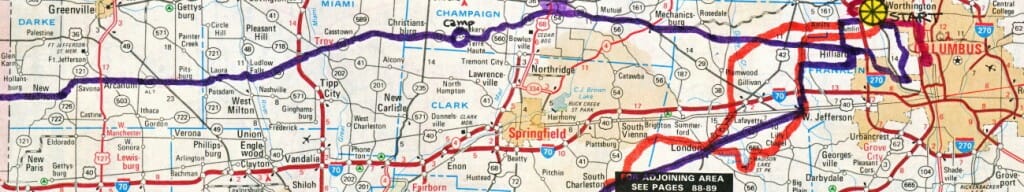

I carefully drew the day’s travel on page 76 of my atlas and put the first quarter-inch red segment on the “big picture” map of the US. I stared at it for a long time before falling into a tormented slumber.

I awoke stiff and sore, groggy from a night of fighting lumps and gravity. I tested the knee nervously, expecting agony but finding only pain, then stretched and emerged into thick morning mist. Everything was soggy with condensation, and the sun was just brightening the tops of Indian summer trees.

Walt stirred at the roar of the stove, and crawled from his tent stubbled and bleary just as the first steaming cup was ready. I handed it to him and made one for myself, brewing freshly ground Costa Rican coffee with a little infuser that should be standard equipment for every camper.

Then, with a sly grin, I withdrew the groceries from the clutter of my tent, tossed bacon into the folding-handle teflon skillet, and started grating cheese. Walt sat in his doorway trying to marshall the energy to pack, uninterested in my futile domestic putterings. But it didn’t take long for the sounds and smells of sizzling to waft across the dewy space between us.

He looked over with an expression bordering on despair.

“Aw, Jesus, you can’t be serious!” He pointed at the previous night’s pan lying forgotten in dewy weeds, encrusted with an appalling putty-like substance and dotted with mushy beans. “There’s gotta be a restaurant in the next town, man — if you start screwin’ around with breakfast, we’ll be here all day!”

I just smiled. “Relax, Walt. Breakfasts are my specialty.” While he shook his head and made disparaging comments about Swedish firebombs, goddamn pots ‘n’ pans, and the number of miles to Richmond, I started the first bacon and cheese omelette. He pointedly turned his back and busied himself with packing.

It was time to turn the eggs. I had packed a nylon spatula for just that purpose, but I was in a showy mood. (Hey, like this was my wilderness debut, OK?) I held the pan above the stove to slow the cooking process and waited for my friend to look over.

At last the moment arrived. With the air of a master chef on television, I flashed him a cocky grin and gave the omelette a toss — perfectly calculated to flip it into the air and return it, inverted, to the very center of the sizzling butter. But… I had never used a pan with a folding handle.

And sure enough, it folded — dumping breakfast across my wrist and burning my forearm.

I masked the pain and stared at the steaming mess in the weeds. What the hell is a hinge doing on a frying-pan handle? Walt shook his head sadly and continued packing while I scooped up the mess and finished cooking. Later that day, as we rode along in the burning sunshine, he made an observation.

“You know something, Roberts? I finally figured out what those goddamn pots ‘n’ pans of yours are good for.”

“What’s that?”

“A bump detector. I ain’t used to being on a bicycle this much, you know, and as I ride along behind you I just listen for a rattle from your goddamn pots ‘n’ pans. As soon as they set to clankin’, I figure I’ve got about three seconds to lift my ass up off the seat.”

“Gee, Walt, I’m glad to be helpin’ you out.”

“I tell ya, you’ve saved my sore ass more than once with those things. I don’t think they’re too useful for cooking, but they sure ain’t bad for predicting road conditions!”

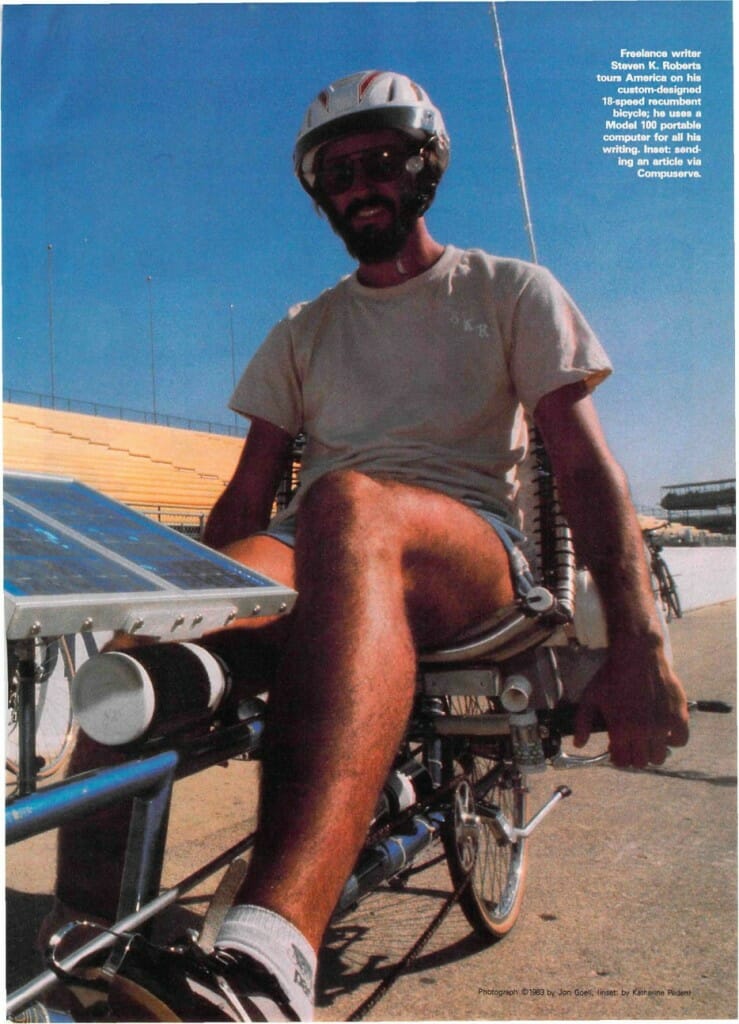

Ah, but this was it. My camping style might still be clumsy and the knee was keeping my speed down to about 12 mph, but this was my element — I found a pay phone in Christiansburg. It was time to check into CompuServe and pick up messages from Kacy, then transmit my “first night” story.

I rolled the bike onto the sidewalk and extracted the Model 100, placing it gently on the pavement next to the phone. The “acoustic coupler” was next — a pair of rubber cups that I fitted to the handset and plugged into the back of the computer. I made a credit-card call to the nearest network-access number and tapped a few keys, waiting for the indication that we were connected.

Beep. No problem.

A few keystrokes identified me to the system, and there I was, hobnobbing on the computer network via my first small-town pay phone. This would become as much of a daily routine as filling the water bottles and checking tires, but at the moment it was exciting, dramatic, and filled with promise. I plopped down on the concrete and went to work, downloading Kacy’s reports of the day’s mail and the media treatment of my departure. Then I went into transmit mode and uploaded my story for her to file.

At first I hardly noticed the old farmer — he was just part of the Christiansburg scenery, a bit of rural background like the modest white houses and mature maple trees. He parked the old Ford pickup beside me with a clank and a backfire, then squeaked open the door and stepped out. I think he was headed for the M & M Restaurant, but when he saw me he stopped, pondering the scene while slowly chawin’ a plug of tobacco.

I looked up and grinned a good morning, and he gave me a nod in taciturn greeting. He walked over in his dusty green coveralls and worn Caterpillar cap, peered at me for a second, then bent to watch the text scroll across my computer’s liquid-crystal display. He glanced at the telephone connection, then squatted by the bike to study it, frowning in sudden concentration and reaching out to touch the steering linkage with a gnarled finger. At last he loosed a stream of tobacco juice into the weeds and squinted hard at me.

“Are yew with NASA?”

It dawned on me at that moment that I had become an agent of future shock — and that this was only the beginning. My new lifestyle was based on technologies that still bordered on science fiction in most people’s eyes, and implicit in the whole affair was a strange message: Not only does this stuff work, but it’s fun.

“Why yessir, this here’s one o’ them Loony Excursion Modules…” We stared at each other for a moment like representatives of alien cultures, then both laughed.

Indiana. The state line slipped by unnoticed, with barely a change of texture to herald the boundary between Buckeye country and Hoosier land. True to our agreement, Walt and I stayed in a Richmond motel the second night, an event marked only by laundry in the sink and the bliss of real beds.

The morning was hot; the land, flat. It didn’t take long to discover that traffic on US40 was fast and rude, so we found a tiny arrow-straight road that took us quietly through the endless golden cornfields of eastern Indiana. The miles blurred together; my eyes were wide open, but I hadn’t learned to see. I passed through without touching, recording memories more of distance than land, more of blue bike and new tan than the colorful folks in the little Mays cafe.

I just cruised along thinking about my machines, my knees, and the profound implications of my new life.

By late afternoon we were nearing the capital, spoiled by three days of rural calm. The first clue appeared as we turned from Post Road onto Raymond Street: a carload of jerks passed, throwing a cup of ice at Walt and some fast-food garbage at me.

We made a few rude generalizations about Hoosiers and continued west at the start of rush hour. This was a rough area and the adrenalin kicked in — speeding us through ragged neighborhoods and depositing us exhausted at the beginning of the Airport Expressway. Some bozo at a gas station told us that this manic highway was the only way to get to the Airport Hilton, so we took a deep breath and rode up the ramp past the NO PEDESTRIANS OR BICYCLES sign.

Lives are fragile. That thought kept cycling through my mind like a futile litany as we competed with Friday afternoon traffic. It was insane, our being there: a violent maelstrom of steel whirled around us, dizzying and exhausting. My knee throbbed and muscles burned as I sprinted frantically across exit lanes, my attention divided between the confusion of the rearview mirror and that of the road ahead.

The only sound was the continuous roar of cars and trucks blasting by in a Big Hurry. A beer can flew past me and sailed over a railing; I looked back and saw Walt, another frightened creature tossed by the powerful cross-currents of this living nightmare.

Far ahead through a thicket of hydrocarbon haze was the blue logo of the Airport Hilton, where Frank waited in a third-floor room with a cooler of beer. I swerved to miss a splash of broken glass, and a horn exploded in my ear — I turned to look and a red-faced commuter sweating in a dark suit angrily gave me the finger. I mouthed a curse that was lost in the storm.

A scowling woman in caked makeup arrived in front of me at an entrance ramp, saw three lanes of traffic bearing down on her, and screeched the brakes of her rusty Falcon. Just as I drew abreast of her, she gunned it and missed me by inches — her target a small opening in front of a cabbie who had to swerve and hit his brakes, nearly causing a pile-up. I felt like a cork in whitewater rapids, with the disturbing difference that corks generally stay on top of things and emerge unscathed. My jaw ached from tension; my eyes burned from exhaust fumes.

I finally shot down the exit with my last available burst of energy and sat dazed and shaking in front of the hotel. Walt pulled alongside a minute later, looking at least as bad as I felt. We dragged our bikes inside and collapsed.

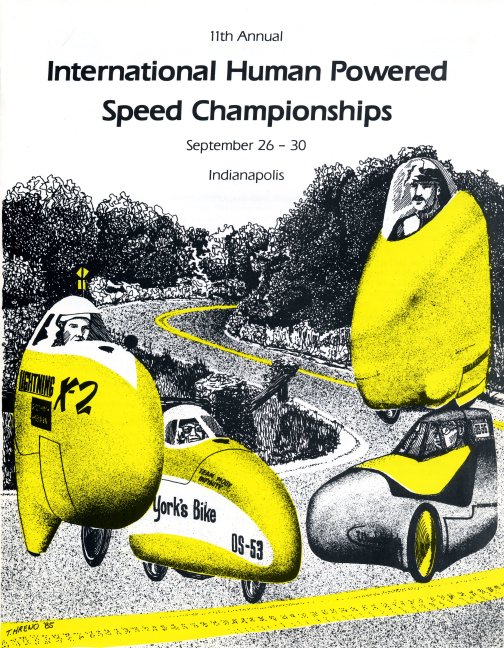

“Gentlemen, start your gentlemen!”

The International Human-Powered Vehicle Races (IHPVA) brought together what must surely have been the most bizarre collection of hardware ever to roll around the famed Indy 500 Speedway. There are a lot of strange ways to put together wheels, pedals, and a seat, and many of the machines here looked ridiculous until they wheeled onto the track and easily exceeded the 55 mile-an-hour speed limit on muscle power alone. It was a weekend of high-tech camaraderie and new world records, of serious athletes and creative tinkerers. In this outer fringe of the bicycle world, I had my first taste of crowds — and it spoiled me terribly.

“Ah yes, a TA crossover. You need to tweak your eccentric a bit.”

“Have you played with a cable linkage?”

“Whaddya end up with fer trail on yer front end there, ‘bout an inch?”

“Whoa! A sixteen by one-and-three-eighths 36-hole alloy rim? Where the hell did you get that?”

“What’s your fore-aft weight ratio?”

Questions like these were commonplace all weekend, for I was in the world of hard-core bicycle experimenters. Only a few days later, I would be hearing instead:

“Um, with that long chain, you still gotta pedal as much?”

“How many people ride that?”

“Where’s the motor?”

“Is this solar heater up here so you’ll stay warm in the winter?”

“Uh, pardon me, how many wheels that got?”

And so on. The difference was startling. I grew so accustomed to chatting with bike wizards that I quite forgot that I’m riding around on a machine that’s alien to most of the population.

It was a weekend of enthusiasm and a weekend of work: I was already facing my first on-the-road article deadline and found myself sitting alone in the Hilton while my friends went to evening races at the velodrome. I stared at the tiny screen, trying to force my mind to think about artificial intelligence research. It fought back like a balky mule, preferring to daydream over road maps rather than focus on the job at hand. But the money…

Would this work?

So far, the trip was proving to be no magical cure for bad work habits — I still reached for the phone at the slightest hesitation in the flow of words; I turned on the TV to see what was on and ended up watching some implausible Knight Rider. That naturally led to sleep, where I stayed until my roommates returned to shame me with questions about progress.

Procrastination followed by despair. It was the same old pattern in a new setting.

Sunday, the races were over. Winners and losers packed their machines into vans and trailers; handshakes and cries of “See ya next year” echoed everywhere. The crowd thinned. Somebody started picking up garbage, and the soft-drink vendor closed up shop and rumbled down the road, trailing a wake of yellow leaves. I absently did an interview with the Indianapolis Star, and then it happened:

Walt and Frank drove over to say good-bye.

Walt’s bike was packed in Frank’s car, and they were on their way back to Columbus and the start of another week. I suddenly realized that I had been depending upon them for support, and that in a sense I had not yet left.

Suddenly I was a stranger in town, on the road alone. I stood quietly and watched my friends drive away.

You must be logged in to post a comment.