The Launch

Computing Across America, Chapter 4

by Steven K. Roberts

September 28, 1983

You ante’d up to play Russian Roulette.

— Tom Hoobyar

The day of departure dawned. Like every morning, the clock radio blared banalities aimed at a mixed audience of commuters and housewives. The guy in the traffic copter talked about “three-block delays on 71” and the deejay bantered goofily between fast-paced interludes of hit singles and commercials. I hid from it as long as I could, then slapped the radio into abrupt silence and stumbled to the shower with something top-fortyish looping through my brain.

It was a routine Wednesday morning. Across the street my neighbor’s automatic garage door opened, emitting the orange Corvette with its low throb that I could feel more than hear. With a Doppler-shifted roar he joined the commuting throng, and all was again silent.

I took my last shower under the familiar hardwater-encrusted Shower Massage. Everything was routine: my choreographed cleansing dance had the same steps. But the event was touched with epic significance, for a new life was beginning. I slid my hands slowly over slender soapy legs and tried to calculate the number of pedal strokes per thousand miles.

New white socks. Cycling shoes. Shorts. Sweats. A “Computing Across America” T-shirt.

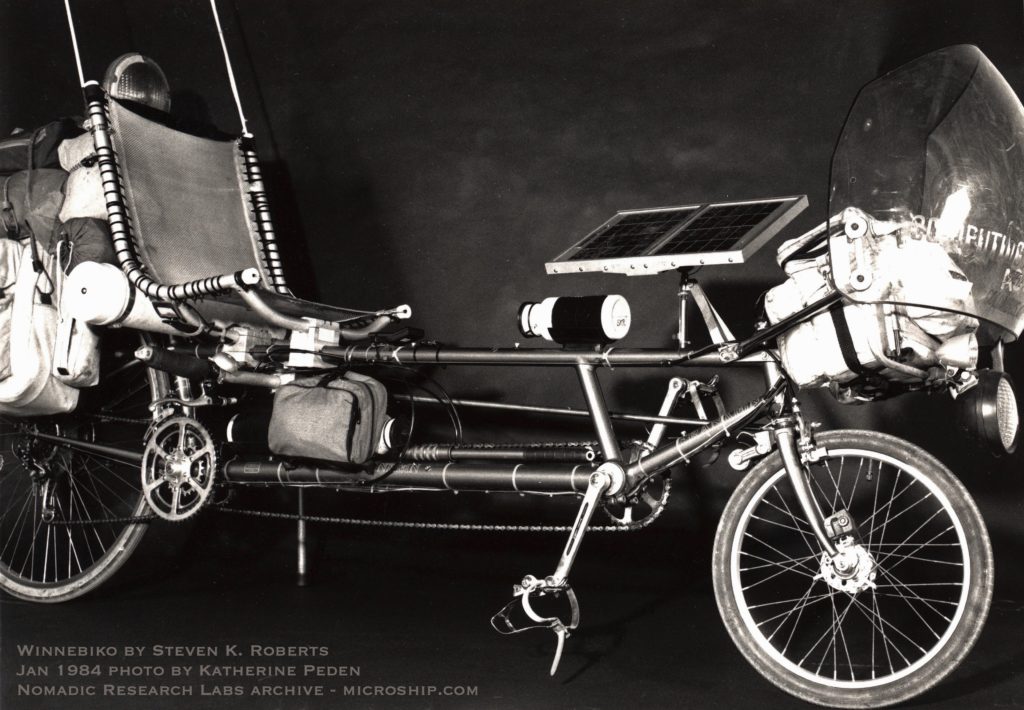

And there in the living room it stood — poised like a cruise missile, a drug, an embryo, a virgin. It was a thing of promise, laden with significance beyond its reality, and it stood in violent contrast to the familiar hearth. Sensing the beginning of a daily routine, I filled the water bottles and checked the tires, then coiled the cord to the auxiliary battery charger and crammed it into its zippered pocket. The bike was ready, unnaturally clean and blue, like a new pair of jeans. I was ready — psyched, excited, a bit nervous, craving coffee, and ready.

I squeezed the machine through the front door and eased it down the steps into the tall ragged grass of my lawn, then rode away without looking back, without regrets. Frank would take care of everything. He would empty the house, clean it, sell it, and handle the closing. Without friends, this adventure would have been nothing but a lawn-mowing daydream as I bounced around my lumpy acre in an itchy haze of grass pollen and Snapper smoke.

One mile. Dublin Road looked different: after four years of living there, I now saw it with the eye of a traveler. The stylized houses were a cultural phenomenon, the developer-staked cornfields a symbol of encroaching look-alike suburbia. I read the license plates, savored the morning chill, and even paused on the approach to the Hayden Run bridge to look at the Scioto River. Damn. Never really noticed that little wooded area before…

I made eye contact with every passing driver, conscious of my eccentricity. A blonde lady enroute to work smiled warmly; two guys in a van stared so hard while waiting at a traffic light that a chorus of angry honks was necessary to get them moving. Startled, they lurched forward and stalled in the intersection. I somehow interpreted this as my fault, so I accelerated past them in embarrassment and threw the chain while trying to shift.

With the pedals locked, I lost control. Piloting this strange contraption was yet far from intuitive, and in the attempt to pull into a gas-station driveway I fell over. The guys in the van passed, laughing, doubtless making jokes about how that yo-yo oughta get hisself a regular bike.

Like a performer flubbing a recital, I fixed the chain and struggled to recover my confidence — flushed and self-conscious as the commuter traffic whizzed by. TV cameras in an hour, eh?

Grumpy and greasy-fingered, I rang Walt’s doorbell. He was taking a few days off work to ride with me to Indianapolis on the first leg of my shakedown cruise, and I pasted a grin over my chagrin as he answered the door.

“Well, you made it! Man, you sure got that sucker loaded down, dontcha? Did you get any sleep last night?”

“Coffee,” I croaked in mock desperation. “How’s it feel?”

“Strange. Beautiful. A little heavy. And I’m having derailleur problems.” I held up a blackened hand.

“Well, there’ll be plenty o’ time to get that straightened out. You’re doing this for a living now.”

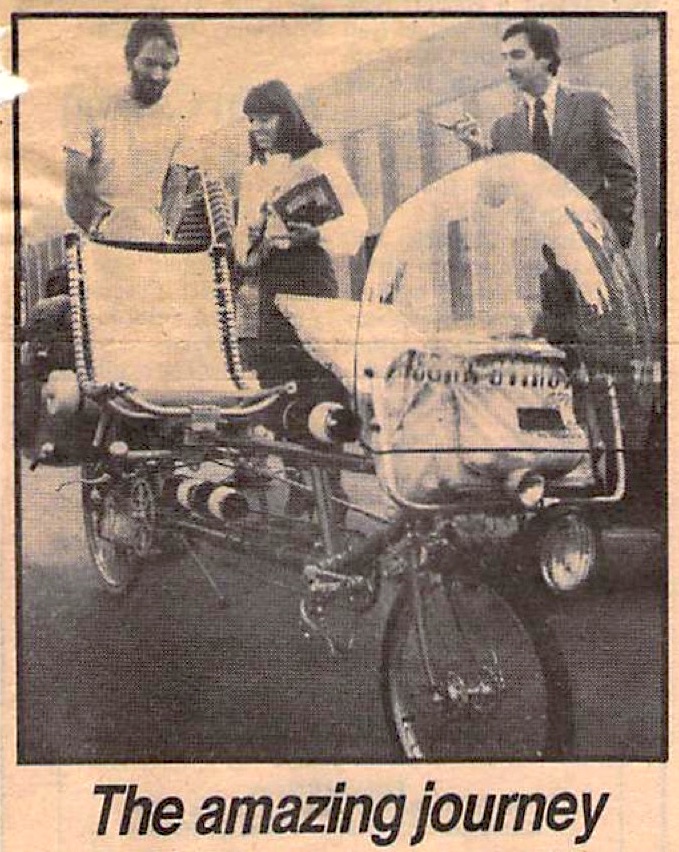

I first saw the “Eyewitness News” van from the booth at Elby’s, and managed to gulp a few last bites of carbohydrates before nervousness brought breakfast to a premature end. Across the street in the CompuServe parking lot, the media were gathering. Channel 4. Channel 6. Channel 10. Press cameras.

Curious people poured out of the building to surround the cordoned-off launching area, and they stood in the morning sun peering this way and that. Where is the high-tech nomad? He should be here by now. Then somebody noticed my bike outside the restaurant and all the faces turned.

“Shall we?” I asked drily.

“Hey, that’s your party over there. I’m having another cup of coffee.” But we paid the bill and rolled across Henderson Road to the sounds of scattered cheers, flashing toothy smiles at the waiting throng as if we were visiting dignitaries. Walt melted into the crowd and I was on my own.

The choice of CompuServe’s parking lot as the departure site was a deliberate one. This was a public-relations bonanza for them: their giant computer network would be my primary communications link with the rest of the world and, along with microelectronics, was a key technology that made the whole affair possible. The company had provided me with free system passwords and an ongoing column assignment in Online Today magazine, and in exchange they were looking forward to media exposure all over the country. It was one of those rare deals in which everybody wins.

With cameras perched like electronic parrots on their shoulders, the TV crews closed in. I was surrounded by microphones, spiral notebooks, lenses, and a flurry of questions ranging from the profound to the absurd:

“Why are you doing this?”

That was a bit heavy as an opener, and I mumbled something esoteric about beating the freedom-versus-security trade-off. The reporter frowned slightly and tried a different approach.

“Can you tell us how many states you expect to cover?”

“I don’t know… at the moment I see the trip as a sort of clockwise loop around the United States, perhaps 14,000 miles or so. I have no fixed itinerary.”

“Do you have any idea how fast the bike will go?”

“Theoretically, I should average about fifteen percent faster than a regular bike, though the heavy load might offset that. I’ll probably cruise at fifteen to twenty, given a good breakfast and no headwinds.”

The reporter, conscious of being on-camera, edged his voice with professional incredulity. “Just a moment. Do you mean to tell me that this machine is entirely pedal-powered?”

“Yes.”

He paused dramatically while his cameraman zoomed back to take in the entire bike. “Then why is it equipped with solar panels?”

“Well, I thought I’d make a little extra money selling power to the utility companies,” I joked, then realized I was being taken seriously. “Uh, the panels actually only put out about five watts — they charge a NiCad battery that powers everything except the wheels.”

“Such as?”

I grinned, starting to relax. “Oh, you know, the usual cycling gear. Lights, horn, paging/security system, CB, stereo, computer — all that.”

The reporter chuckled, assuming I was still teasing. “And the microwave too, right?”

“Not yet, but there’s probably a satellite earth station in the bike’s future.”

Another news personality broke in. “Excuse me, but could you elaborate on the computer? Why would you want a computer on your bicycle? And, uh, where is it?”

I stepped to the back of the bike, unhooked a few bungee cords, and removed a cordura pack. With a few zips it fell open to reveal the Model 100, which was, at the time, the only lightweight portable computer on the market. There were murmurs and low whistles all around.

“This,” I said, holding the machine up to my chest, “is my link with the universe. You can think of it as the control panel of my remote-control office, if you like — I have a conventional personal computer system here in Columbus along with a human assistant named Kacy. Communication between us takes place electronically through the CompuServe network.” I gestured over at the building.

“But why do you need all this on a bicycle trip? Isn’t this a rather fancy way to get the mail?”

“More than that. I’m a freelance writer, and this setup lets me edit and transmit text, stay in touch, and maintain the illusion of stability. I’m not independently wealthy, so I’ll have to work pretty hard to keep the adventure going.”

“Well, that’s amazing. Could you hold the computer up a little higher for a minute? There… OK, now point to the keyboard…” Three cameras converted the event to video.

“Uh, I might add that the network is also my link to a stable social life — as I travel, I’ll be staying in touch with friends electronically, sometimes meeting them online in real time. That should keep the traditional loneliness of the traveler from being a problem.”

This was getting a bit abstract for the evening news, though CompuServe officials looked on with a sort of subdued glee. I went on to explain the network — a growing global community of people linked not by physical proximity but by personal computers and telephones. As I spoke, I had a sense of the bike as a human-powered moving van, relocating me from my cramped quarters in physical space to a spacious new home in Dataspace. But their questions returned to specifics. “How long will you be on the road?” (Six-foot-four)

“How many gears does your bicycle have?” (Eighteen)

“How much did all this cost?” (Initially about $8,000, including accessories)

“Where will you sleep tonight?” (Who knows?)

“Do you carry a gun?” (No, and if I did I wouldn’t announce it on TV)

“What will you do when it rains?” (Get wet, probably — though I have Gore-Tex rain gear and pack covers)

And so on. With the cameras following every move, I performed the obligatory figure-eights, hugged friends, and shook hands with CompuServe management. It was time. People began drifting away, back to the Wednesday routines of the business world.

Elisse stood apart from the crowd, quiet and accepting. I walked self-consciously over and held her, sensing that there might be another, more personal level to this freedom-security issue. Ahead lay the Unknown, and breaking that last familiar kiss was like the severing of an emotional umbilicus.

Walt glided across the parking lot. Beside him was the worn black Avatar bearing the unwitting catalyst of all this, and behind Robby rolled three local cyclists, anxious to vicariously share the first few miles of adventure.

At last the journey was underway. The Robert Plant song wafted through my head in time with the motion of the pedals and the clicking of my right knee, as the traffic of Columbus gave way to the silence and smells of farm country.

You must be logged in to post a comment.