The Fulmar Adventure

There was an interlude in the Microship project that I remember fondly… a brief foray into an off-the-shelf boat, simple systems, and emphasis on adventure over geekery. After a year or more of over-engineering, I bought a Fulmar-19 to fast-track our way to the planned expedition, and this is the rollicking story of the maiden voyage. Alas, there were a few practicality issues that were deal-breakers, so I returned to the lab to sell this boat, buy a bigger one, change my mind again, spend five years building a pair of Fulmar-scale Microships that addressed the issues noted on this trip, get sidetracked by a backpack-scale project, buy another big trimaran, sell that after finding it impractical for full-timing, settle on a gorgeous steel 44′ monohull, then get stuck at the dock with back problems and move to a 50-foot Mothership with a crane-launched dinghy on the roof. What a long, strange, trip…

September 17 – October 1, 1994

by Steven K. Roberts

Inhalation

It’s all just an abstraction, really, until you actually DO it. For three years I’ve been reading, planning, designing, learning, and even getting out on a boat now and then. For Faun, it has been even more of a change: we met, found ourselves sharing the same dreams, and decided virtually overnight to go for it. Late nights in the Microship lab and a few sailing classes on placid Mission Bay comprise her background; mine, though more extensive, includes little more in the aquatic reality category but for a few day sails and a bit of kayaking here and there.

No matter: lack of experience never stopped me before. Full of grand visions of sparkling sunny days and erotic nights in cozy island campsites, we piloted the diesel truck up the coast from San Diego to Seattle, stopping to visit sponsors and friends, standing with them around the trailered Microship and explaining the dream. “Well, after this little 2-week shakedown in the San Juans and Gulf Islands,” we would say blithely, “we’ll spend a few months integrating the rest of the systems and then truck to Juneau, sail down the Canadian coast, haul them to Edmonton, traverse the North Saskatchewan River across Canada to Lake Winnipeg, hop down to Lake Superior, then cruise down the Mississippi, through the Gulf, around Florida, and up the ICW to Maine. Then Europe, of course.”

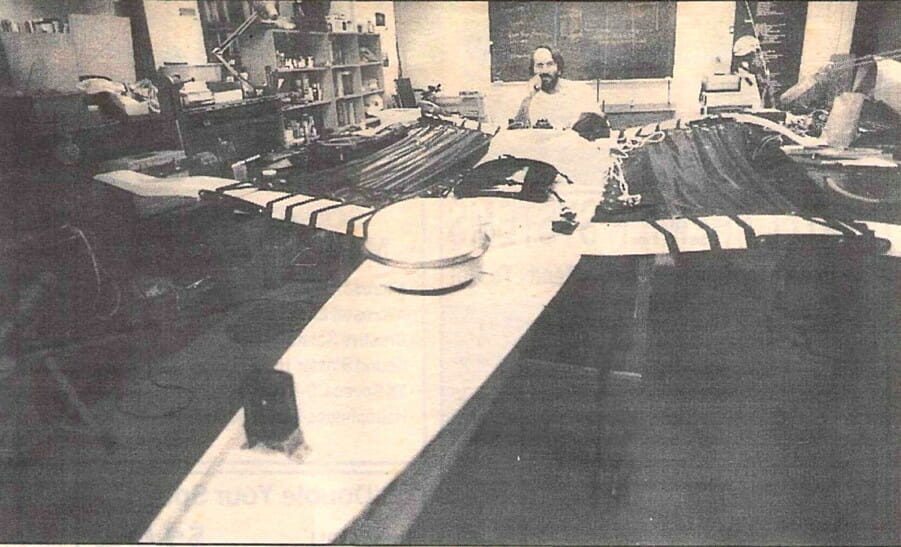

They would nod sagely and offer bits of advice, while we’d glance at each other and try to imagine actually living on a pair of tiny Fulmar-19s. These are trimarans on the scale of kayaks, with center hulls 27″ wide and a few wee hatches for gear. “Kayachts,” I call them. I’ve located a second one for Faun, thus forming the world’s largest flotilla of Fulmars (only about ten exist), and we spend much of our time puzzling over packaging, gear choices, and systems integration. Making the jump from pleasant day sails to 10,000 miles of open-ended wandering is quite the extrapolation.

First things first. We arrived in Seattle, borrowed a boat for Faun from Saint Cy, spent two days in frenzied last-minute preparation, and launched for the 2-week maiden voyage…

All-nighter: Seattle to Port Townsend

By the time we actually assembled some 300 pounds of gear and dealt with the complex logistics of two boats, two trailers, and one truck, it was 16:00 on Thursday, September 15. No problem, we’ll just sail to some quiet little town like Kingston or Port Ludlow, find a B&B, and then zip on up to Port Towsend in time for my talk at the Sea Kayak Symposium the next day at 14:30. Hey, we have 22 hours… piece o’ cake.

We set out from Shilshole Marina in the Ballard area of north Seattle with many a sparkling grin and comments along the general line of “can you believe we’re really doing this?” All our senses alive, we noted every little shore feature, ship, and scrap of flotsam. Of course, there was no wind to speak of, so it was 3 hours of pedaling before we entered Appletree Cove and approached the town of Kingston — the sun low in the sky. The plan, simply, was to dock and find food, then decide whether to spend the night or press on.

But the wind, that sly vixen, seductively rippled the water and filled our sails. Rainier’s snowy peak glowed orange in the low angle light of sunset. The Edmonds ferry blasted her horn as we sprinted across her bow <gulp>, a HANJIN freighter scudded north in the traffic lane, and distant city lights twinkled crisply atop their rippled reflections. How could we stop now? In no time we had rounded the point and were beating northward, dancing, racing across sparkling water — high on the wind, on each other, on adventure. I pushed my vague misgivings about night sailing into the background and set course for the Point No Point light.

Three hours later, in darkness, we rounded the point. It had been a long beat into the wind, but the night was yet young and hey, there was a sense of delicious madness afoot. The plan now was to scoot over to Foulweather Bluff, round that, and duck into Port Ludlow around midnight to look for a place to sleep.

For some reason, though, the going became painfully slow as soon as we rounded the rotating white light of the point. We became deeply familiar with the houses on shore, one by one. We would pedal hard to go nowhere; then try tacking out only to return to the same point. Hm. After about an hour of this death march, the growing strength of the flood current was painfully obvious: we were like insects trying to claw our way up the faucet that was filling Puget Sound. I kept staring at a point that marked the mouth of Skunk Bay (and its imagined respite) less than a quarter mile ahead, but it became clear we could never make it.

Fortunately, someone had installed a mooring buoy, and I struggled up to it, snagged it with my boathook, and tied up. From this perspective, the current was obvious — raging and bubbling past me like a fast river, bull kelp streaming along the surface, my dropped Petzl headlamp scooting rapidly back to Seattle. Faun worked her way over to me and we rafted, then congratulated ourselves and wolfed down peanut butter and jelly while enjoying the novelty of the craziest midnight we’ve seen in weeks. Little 2-inch jellyfish zipped by, flashing bright green when touched; wee organisms did likewise and turned a sweep of a hand into a mini-constellation. Despite the exhaustion of the struggle, there was magic afoot…

The attempt at sleep was unsuccessful. Slack was scheduled for 02:22, and we stretched out on the tramps to wait. But the boats were banging together in a rather distressing fashion (fenders notwithstanding), and water kept working its way between me and my Therma-rest, puddling atop the non-porous fabric of the tramp as I shivered under a wind-whipped space blanket. Another few items for the TO-DO list…

Just before slack, the current down to about a knot, we decided to cast off and continue. Faun untied her boat and drifted downcurrent… and kept drifting. A frightened voice from the darkness: “Steve? I need help. The pedal drive is jammed.” Kelp, no doubt. As I worked to free myself from the buoy, she sailed toward shore — the composition of which was unknown.

It turned out to be sand, fortunately, and I sailed over (through a kelp bed) to join her. At this point, a serious temptation presented itself: camp on the beach under the trees and deal with it in the morning! However, there was still that speaking gig 20 miles away, so after a brief respite we set off again. Faun was having a few doubts, especially when I pointed toward our ominously dark destination.

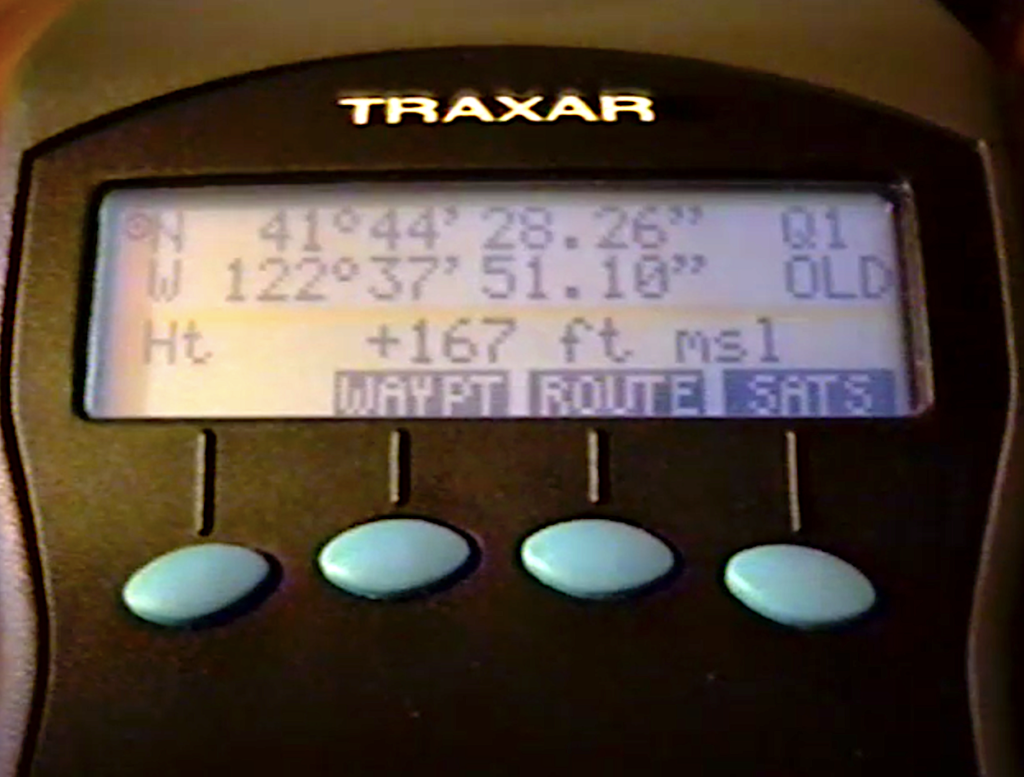

Those doubts deepened significantly when the fog rolled over us. Within the hour, at about 03:00, we were engulfed by soup, sailing by GPS alone. The blue backlight of the Motorola Traxar, red and green spray flying past the navlights on my bow, occasional bioluminescent sparkles from the deep, and the rollicking nav lights of my partner became my world — Double Bluff and Mutiny Bay somewhere ahead. I checked Faun’s status via the Motorola GMRS handheld radio: “worried” came the answer in a voice small and unfamiliar. But the fog parted for a few minutes to reveal a dramatically clear night sky, and sure enough, ahead lay the green beacon of the point and a row of lights edging the bay. We savored the luxury of visual reference points…

But stopping — even if we were lucky enough to find a place — was out of the question, for now it was nearing ebb. It would be insane to sleep through a favorable current only to wake in time for a contrary one, so the decision to press on was unquestioned. This was to be a long reach — about 9 miles up Admiralty Inlet. Again the fog… and with the moon setting there wasn’t even a hint of skylight to provide differentiation between water and sky. Just thick blackness, the microworld of a tiny boat, and the immediate waves — nothing more.

This leg became a mad dream, a wild ride of sheer exhilaration and absurd risk. Running 7-8 knots on a close reach in favorable current, we trusted our lives to the miracle of GPS. Faun’s job was to keep my lights in sight; mine was to maintain the heading that would clear Marrowstone Point while trying not to think about the fact that we were screaming northbound in a shipping lane in the fog. Indelible in my mind is the image of my friend in a sleek matching boat, flying beside me, crashing through waves, soaked and cold, completely dependent upon me and the technologies that provided our flotation, navigation, propulsion, illumination, and communication. This was deliciously mad and totally consistent with the spirit of adventure.

(“Adventure,” quoth a friend, “is the result of bad planning.” But I prefer to think of it as the whole POINT of planning.)

It seems that the spaces between waypoints are chapters, for each turn, while part of the same overall trek, adds new and unexpected twists to the evolving story. The next chapter was home stretch at last, and given the northeast wind I was eagerly anticipating a nice broad reach on the last 3.9-mile jaunt to Point Wilson, just north of our home for the weekend. At dawn we rounded the horn that had been teasing us for two miles, turned eagerly west, and… and… so did the wind. Thick white fog and a headwind. Lovely. <sigh>

Slog on. For three more hours we kept at it, cranking our throbbing legs, hallucinating land and ships, numbly alert to the horns and rumbles of freighters and ferries around us. It seems so tame now, looking out from the cliff on this clear sunny day in Port Townsend, but in the soup after an all-nighter it’s sinister and exhausting. Faun had to laugh at me: startled by the too-close chest-vibrating foghorn of a ferry, I responded with my whistle — a contrast too silly to contemplate. But they weren’t monitoring VHF channel 16 and I had to try something… moments later the monster materialized not 100 yards away, growled implacably past, and dematerialized so quickly that it seemed but another hallucination of fog demons.

I steered for the Port Townsend horn to take advantage of a close reach, then turned north for the final couple of miles, but even THAT was to be a challenge. Not only were we proving that wind always originates from one’s destination, but the currents had returned with a vengeance: it was 10:30 when land finally ghosted into focus. My exhausted brain called out to Faun, “there it is! See those big buildings up on the cliff? That’s Fort Worden!” The “buildings” were actually a line of driftwood resting on the beach at high tideline, but I was on the right track… a few minutes of drifting easily landed us in a cluster of unencumbered sea kayaks. My first thought: “What? They came here by CAR???”

Distance made good in those 16 hours: 39 nautical miles, 30 as the crow flies, about 60 if you count all the tacking. We do like to jump in with both feet, eh?

Speaking of jumping in, Faun is a remarkable partner. We’ve known each other but two months, and in that time she has quit her job and plunged into this project. She’s a great worker, an ideal companion, curious and alive… and even the sponsors adore this young 6-foot ex-model with the ready smile and Big Ideas. Our two-week maiden voyage is a test of more than boats… we’re learning more about each other than the past 6 weeks of living together could even begin to reveal. The plan to purchase a second boat seems to suggest more than casual optimism with regard to the longevity of this relationship… there’s nothing like surviving a night at sea to forge a bond deeper than any number of hot dates.

This update comes to you from the second day of the Sea Kayak Symposium. I somehow survived my somnambulatory speech and am learning from others; we’re sore-legged but recovering; the boats are presumably still at their moorings (yes, I’m paranoid about security); and we launch tomorrow for Port Angeles — our jumping-off place for the trek across the Strait of Juan de Fuca to Victoria.

The John Wayne Marina

Well, we did indeed launch for Port Angeles, but didn’t get that far in one day, or even two. Actually, we didn’t get there at all — that’s part of the reality of sailing.

By the time the currents allowed us to move significantly west from Port Townsend, it was getting late… so we gave in to temptation and made for Sequim Bay. Now, on the chart, this looked inviting — a quiet little corner between Discovery Bay and Dungeness. It was dark by the time we slogged into the mouth of the bay (oddly, both ebb and flood fought us on the same compass heading). I can’t emphasize enough just how demoralizing it is to pedal into current without the aid of sails: it’s much worse than bicycling into a headwind, where you at least have solid ground to push against. Here, you push against something that is moving the other way…

Exhausted, we poked in the dark around Washington Harbor, expecting from the name to find, well, something vaguely akin to a HARBOR. I was already soaked from the waist down from an attempted beach landing on a ragged hell of rocks and shells, and we found ourselves peering into blackness with inadequate flashlights, looking for anything to tie the boats to. On a hint from a bemused local, we pushed one more mile to the John Wayne Marina.

Now, marinas are not made for people like us. Most boats that patronize these places are yachts, and either accommodate sleeping on board or discharge arriving yachties into their cars. But we staggered onto the dock asking weird questions about tying up two baby trimarans (“that one is my dinghy, you see — can we just pay for one berth?”) and pitching a tent, and finally proceeded to camp with the warning that we had to be out by daybreak. And while this did solve the evening’s problem, it also demonstrated that marinas are not necessarily the place for tiny little boats.

Shipwrecked on Dungeness Spit

Morning. Dead air again, but in good spirits we pedaled north, making for the tip of Dungeness Spit, slowing to enjoy the shallows, taking a break on a beach, gently raising the idea that maybe we need a larger boat that can accommodate sleeping. Dungeness would be the turning point at which we would either launch across the Strait or run west for Port Angeles, but we spent most of the day getting there.

“Let’s swing around the buoy,” I casually said as we at last drew near, “there might be some rough tide rips at the point.” As it was getting dark and cold, I turned my attention from sailing to wriggling into Kokatats.

By the time I looked up, the buoy, once dead ahead, was a mile to port and receding fast. We were in a killer flood current pushing us east, and were absolutely unable to find any combination of pedaling and sailing that would yield westward progress. The range to Port Angeles was 15.0 miles, quoth the GPS — and there it stayed, unmoving for over an hour, as we tacked back and forth, trying to avoid losing ground.

At last it relented somewhat and we began clawing our way in rising wind along the outside of the spit. We would tack out into freighter-land and then zoom back into kelpville, beating toward the imagined respite of a state park noted in my DeLorme atlas. There had to be a landing, for we could see a dense fog bank closing and the sun was going down. Around here, night sailing in high wind is risky business — the sea is peppered with serious hazards in the form of floating logs and deadheads (logs floating just below the surface). Thrice in this windward beat I had to veer to avoid a collision.

The wind was growing, the seas capped with white foam. To our left, rolling waves arriving from the Pacific crashed on the driftwood-strewn spit, a profoundly inhospitable place for boats. But the darkness and fog were closing, and Faun was pulling ahead due to a recent misalignment in my two mast sections (normally we’re well-enough matched in sailing performance that we use each other for sail-trim feedback).

I watched in horror as she made straight into the surf zone. A couple of tourists on a sunset stroll stopped to stare. I thought to yell, but she was too far off and the handheld radio batteries were dead… I saw her boat start to bob, then pitch violently… then hit the beach and broach in the surf. One wave swung her broadside, and a moment later she was up to her neck in water, struggling with the boat, trying to drag it up a steep drop through dumping surf. Finally, the gawkers moved to help and within moments she was — for the moment — safe on the sand.

Great. There was no way she was going to get off that beach under these conditions, and because it was low tide, the boats would have to be hauled some 50 feet into the tangle of driftwood to survive the night. Darkness was closing rapidly, the wind was howling in my ears, and a dense wall of dark orange sunset-backlit fog was nearing. Port Angeles was still over 10 miles away, directly into the wind, and there was no other place to land. OK, here goes…

I made one final tack to approach orthogonal to the waves, and made straight for the beach, Faun watching wide-eyed. As I felt the surge of the surf, I had idealistic images of riding smoothly onto the sand and hopping out to drag the boat kayak-like up the beach, but it was not to be so simple. The boat hit the beach hard, veered, took a wave that filled the cockpit, washed out, slammed again… somehow I found myself in the surf hauling on the bow painter, aided ineffectually by the strollers who were being careful not to get their feet wet. Every wave slammed the rudder hard to port, bending the yoke; the hulls ground on the rock-strewn beach and gave up precious gelcoat with each painful scrape. I shouted directions to the locals, and somehow we dragged the boat half out of surf — giving me enough time to frantically pull drybags of gear out of flooded hatches.

We finally pumped out and, with four groaning people, hauled the Microship and her sister ship up the beach and into the tangle of bleached logs above tideline. By now it was fully dark and the tourists beat a hasty retreat, leaving us with the amusing task of pitching camp in heavy wind and wet sand. Everything was sodden and gritty, and it was nearly 23:00 by the time we shivered into our Caribou bags and tried to sleep. I set my alarm for 03:45 to monitor the boats through high tide.

Through all this, we were mildly paranoid about getting caught camping in a wildlife refuge, but hey, any port in a storm. As it happened, the ranger was a friendly fellow, somewhat amused by finding two baby trimarans and a tangle of gear on the spit. With more help from strollers, we aimed the boats at the beach in morning light, waiting for a high tide to provide a window of gentler surf that would lift us off. But two strapping lads came by, stripped down to shorts, flexed their muscles for Faun, and launched us straight out to sea — to hell with counting the sets, this looks good, HEAVE! She almost pitchpoled backwards in the next breaking wave, but we made it.

Death March Across the Strait of Wanda

It seemed surreal, all of a sudden, to be afloat, the now-sinister Dungeness Spit slowly receding. Ahead lay Canada, only 20 miles away, and we had happy images of a long skimming reach in the legendary winds of the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

But the water, within the hour, became so glassy that we could read each other’s sail numbers in the reflections.

Ah well, deploy the outdrive and pedal. And pedal. And pedal some more.

For ten hours we pedaled.

It had its moments, of course. An odd optical illusion that looked as if a giant tidal bore was bearing down on us from the entire eastern horizon. A dolphin arcing through the water before my bow. Ham radio autopatch contact with David Green in Victoria, informing him of our ETA. The rich beauty of sunset, mauve and peach blended and swirling gold-speckled through a sea muscular with ocean swell. Moonrise, full and huge behind Faun. The close encounter with a freighter. Chat with the friendly Victoria ham community, concerned for our safety and monitoring our progress. Occasional weather reports on the marine VHF, forecasting calm on the strait. The painfully slow increments of the Traxar coordinates; calling out a new mile marker every half hour as we fought our way into the current at about 2 knots. Slowly nearing lights of the city…

And suddenly, impossibly, the passing of the green light, and then the red one, and dark Victoria harbor with Dave waiting in a dinghy… pedaling that last mile to the customs dock between seaplanes and a megayacht with helicopter perched on the afterdeck. “I feel like I’m in Disneyland,” said Faun in a weak, slurred, exhausted voice, gazing past toys of the rich at the gaily lit parliament building. We had just pedaled a half-ton of stuff over 20 miles. After clearing customs by phone (this silly process now reduced even further to absurdity: “are you carrying any weapons? do you have any drugs?”), we were hauled to Dave’s house and tucked in.

But Victoria was a treat. The next day didn’t exist for Faun, who slept on into evening, but I lined up a possible staging area for Microship development and explored the town. Parts of Victoria are “behind the tweed curtain,” very British, but the whole place exudes a sense of cleanliness and culture. Intriguing… would completing a high-tech project here entail stiff trade-offs of cost and access to tools?

Realizations in the San Juans

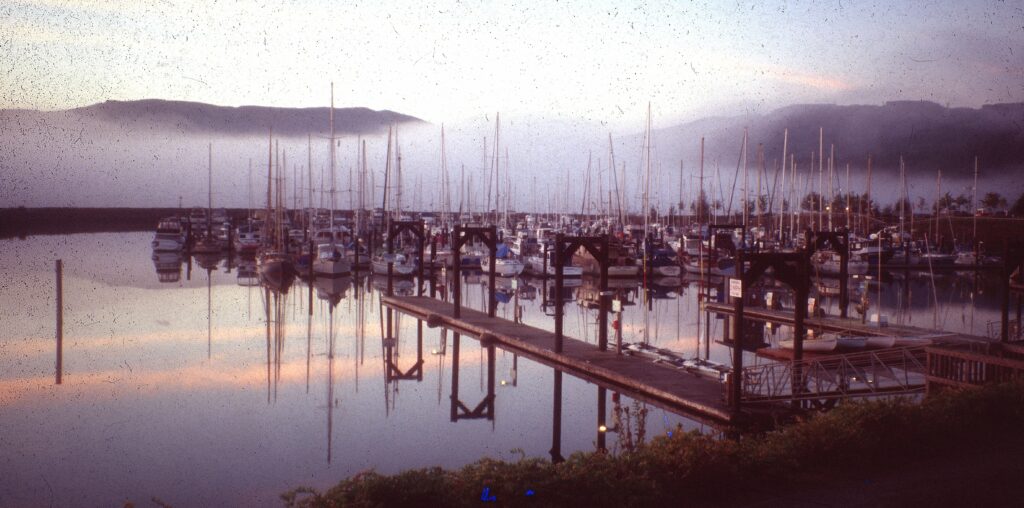

I write now from Greg Riker’s cabin on Henry Island, facing Mosquito Pass. It’s Saturday dawn, and the stinkpotter exodus is in full swing as the recreational fishermen race out into Haro Strait for the day’s kill. Our boats, tiny and frail, bob about on their shared mooring buoy as the motorists zoom past. They remind me of various breeds of dogs: big stupid galumphing ones with fenders gaily slapping the hull, squat vicious ones kicking up absurd wakes, little dainty ones puttering precisely along, lean racing ones flying across the watertop, expensive purebreds parading in coiffed statuesque splendor, scatterbreed mongrels colored primer and dirty white. But all are annoying to a sailor.

The past few days seem dreamlike… exploring Victoria, getting to know Dave and his family (world travelers fresh from an extended stay in Fiji), making a pleasant day sail from the inner harbor, through the tide rips at Trial Island, around to Oak Bay Marina (our first daytime landing, and the annoyance of paying for TWO boats at 75¢/foot even though we take up less space and volume than a typical yacht full of people). By the time we launched for the trek to the San Juans, we were feeling attached to the town, and it is a real possibility for the next phase of the project: excellent cruising grounds, active maritime culture, and 2,000 square feet of proffered ground-floor space in an old shipyard now given over to high-tech companies. Hmmm.

In the meantime, we find ourselves on the northwest end of the islands after another windless 11-mile pedal, in sudden need to move quickly in order to make it back to San Diego in time for a 10/7 Sony speaking gig, with various essential stops enroute (including Reno, to look at another possible Microship substrate). The thought of rushing through the San Juans is depressing, for we’re already getting a sense of the place — island languor mixed with the frenzy of tourism, sharp contrasts between land and sea, potential orcas, and beauty in many forms. But the trip has fulfilled its purpose.

Yes, this has been a significant learning curve. The point of this adventure was to take a reality check — to shake down the boats, camping methods, and even our relationship before committing the next year to Deep Integration of Major Systems. Almost immediately, we started discovering little things — solid tramps are horrible, plastic water bottle cages don’t work upside down, boat-to-boat radios need to be built in, an 18-watt solar panel is not enough, the original Leatherman case needs to be replaced with cordura/velcro, Faun needs her own GPS also, and so on. But the bigger realizations grew as we dealt with the daily realities of finding places to sleep and shuffling packs. The Fulmars are exquisite, high-performance little boats for island-hopping, camping trips, and day sails. But for extended travel on the order of years, I don’t think they’ll do the job. These aren’t like bicycles, which allow you to get off for almost all activities besides riding, yet they impose the same packing constraints. My Sony TR81 video camera, for example, is inside its waterproof case in a Cascade Designs dry bag in the aft hatch… where it has stayed for the whole trip because it’s simply too much trouble to raise the solar panel, haul the duffel and lumbar packs onto the tramps, pull the boat bag out of the way, drag the video pack into my lap and unroll the closure, take some footage, then repeat in reverse — especially since so many things worth capturing on video, like that insane first night, involve rough stuff that would make the whole process too risky or troublesome.

Likewise the sleeping issue. Sleeping on board could be accomplished by tenting over a tramp and the center hull with a Kelty Domolite, but that’s a fair weather, low wind option only. More to the point is the daily problem of beaching or docking — the former a pain in tidal zones since the boats are too heavy to drag above tide line, the latter twice as expensive for a couple as being in one boat. Again, I’ve been spoiled by BEHEMOTH: I just pedaled to someone’s garage or other facility, set security, and slept. We’ve spent hours trying to moor the boats safely, get our stuff to shore, and relax without fear of pilferage or other problems. (In Victoria, they spent a night in greasy water near RCMP-impounded bilge-pumping derelict vessels, easily reached by anyone who would choose to dig through them for $500 drysuits and bags of highly marketable marine gizmology. The sludge took 8 hours per boat to scrub off.)

A larger boat would let us sleep on board, take advantage of marinas on occasion, improve security over bags and cloth hatch covers, anchor out and kayak to shore, and still beach when appropriate. So now the task is to find one that is still small and light, amenable to the implementation of pedal and solar drive, and possessed of that ineffable magic loosely characterized as “high-WQ.”

But for now, onward to Seattle… we’re taking a day in the Henry Island cabin for me to write and Faun to take a first pass at amortizing $140 worth of fishing gear purchased during a last-minute parking-ticketed frenzy in Seattle (5 good salmon dinners-for-two, we figure)… then we’re eastbound through the islands and south to close the loop.

Yacht Crash on the Mighty Swinomish

The San Juans were indeed an amazement, though I’m glad we did them off-season. We actually managed to snag one of the four mooring buoys adjacent to the tiny Blind Island State Park across from Orcas, though we had to hitchhike on the dinghy of a neighboring yacht to get ourselves and our camping gear to shore. Hmmm, that problem again.

We did do some real sailing, however, a treat after endless exhausting miles of recalling the headwinds and hills of yesteryear. The Fulmars are so low to the water that an 8-knot sail is an adrenaline-pumping thrill, and we scooted through narrow channels, past yachts and ferries, out across open straits, around wooded islands — dancing together and flashing thumbs-up across sun-sparkled water. These are the moments that make the others worthwhile.

At James Island, we camped for a night on a hilltop with a view of Mt. Baker alpenglow to the east and the tiny cove to the west… and the beady eyes of raccoons all around. The first inkling of trouble was the sound of a zipper as we dined on pasta at the picnic table in candlelight — I switched on my Pelican headlamp and sprinted to the tent only to find an entire unopened bag of Fig Newtons gone. These guys play for keeps! A few moments later we heard them scrapping and fighting in the woods…

(They also invaded the boats. Faun’s, rafted to mine at the dock, was hardest hit — covered the next morning with muddy footprints, scattered garbage, and the remnants of food wrappings. Faun meets fauna.)

We didn’t know it yet, but the next day was to be our last on the water. After slowly crossing Rosario Strait and working our way down to the famed Swinomish Channel (the alternative to the entirely TOO exciting Deception Pass, whose raging currents sometimes reach 8 knots), we enjoyed a tailwind cruise in favorable current all the way to the little town of La Conner. I ducked into the guest dock and managed a smooth docking maneuver, then called Faun on the radio to tell her I had found a spot.

“I’m out of control!” she cried. “My pedal drive is broken!” Drifting with the current, with no steerageway in the tailwind, she bounced off one luxury yacht, crashed hard into another, then clung tenaciously to land and managed to tie up. This naturally triggered a rather bemused reaction from the yachties, whose first and natural response was to invite her aboard for a drink.

By nightfall, it had been decided. An inaccessible shear pin on her pedal drive had failed, and it made little sense to attempt an on-water repair. We spent the night on the yacht, borrowed the skipper’s car, recovered the truck from Seattle, and made 5 back-to-back drives to return the boats to their starting point.

Microship, Rev 3.0

And so ended the transition between two major design revisions. The trip was a grand mini-adventure, at once stimulating and sobering, a superb learning curve and reality-check. The Fulmar is now in Seattle, up for sale <sigh>, and I’m back to the drawing board. The electronics tools won’t significantly change, of course, but the substrate will be something different entirely.

Here we go again… stay tuned.

You must be logged in to post a comment.