The Hacker’s Shack

Transceiver from a spectrum analyzer and tracking generator? Here’s a glimpse of a hacker’s shack before SDR.

by Steven K. Roberts N4RVE

73 Magazine

January, 1989

This is an interim of sorts — a time of misleading stability between bouts of nomadness. It’s a respite from tire itch, a chance to develop a pot belly with unspent kilocalories, and a time to collect new equipment to further burden the already overloaded bicycle. Maggie and I are in a Silicon Valley layover, dedicated full-time to the creation of the Winnebiko III.

In the coming months, there will be plenty of space in these pages to discuss in satisfying detail the components of the new bicycle-mobile supershack. I’ve just started surgery on the multimode Ranger 3500 (for the 10 meter season is upon us), and many other strange projects are beginning as well. But I want to take a different approach this month, one inspired by the Hacker’s Conference, rooms full of state-of-the-art test equipment, and a mad vision of future radio.

Bizarre and Colorful

A hacker, contrary to the recent slanderous allegations of CBS News, is not a computer criminal or some kind of evil-minded revolutionary. Those do exist, of course, but not in the subculture of creative genius that lies behind every new technology. A hacker, quite simply, is one who derives the greatest possible pleasure from circumventing limitations; a designer who leaps the boundaries of convention, pushes new ideas past the skeptical mainstream of an industry, and stays up all night in the wild-eyed fervor of creative insanity. Hackers are a bizarre and colorful bunch, and when I attended a whole conference of them in the Santa Cruz mountains this month, I witnessed an unrestrained intellectual energy that was almost frightening. It certainly seemed to frighten CBS… which showed images of my bike while speaking ominously of a band of revolutionaries gathered in the hills, plotting their next attack on the valley below.

The hacking phenomenon is generally associated with computers, for it has spawned such phenomena as the Mac, Hypermedia, and all manner of whiz-bang software and graphics magic. But any technology with a future is, by definition, eminently hackable… so let’s consider the “radio hacker” and what his or her station might look like.

The Ultimate Rig?

First of all, let’s agree on something. This rig has to be realistic, something you could assemble today. We’re talking real technology here, not dreams of future offerings from the Big Three. The fantasy is that these tools will someday be available for less than the hundred grand that they would cost right now…

One of our general requirements is total agility in the electromagnetic spectrum, along with the ability to generate and demodulate any communication mode. We should be able to track mysterious signals, even if they’re drifting, and determine their spectral content. We need to freeze events in time, pretriggering if necessary. All types of signal encoding, analog or digital, should be emulated in software. There should be plenty of clean power to the legal limit, robust antennas, and convenience features such as total remote control and automated operation. And, to satisfy the hacker within, there must be endless reserve capability for trying out new ideas and probing the limits of existing systems.

In a sense, any radio receiver is a spectrum analyzer, but one with a narrow window that moves with the cursor. What if we opened up the view of the spectrum, covering the famed “DC to daylight” range at any level of magnification? It turns out we don’t have to invent this at all; they’re available off the shelf from Tektronix and Hewlett-Packard.

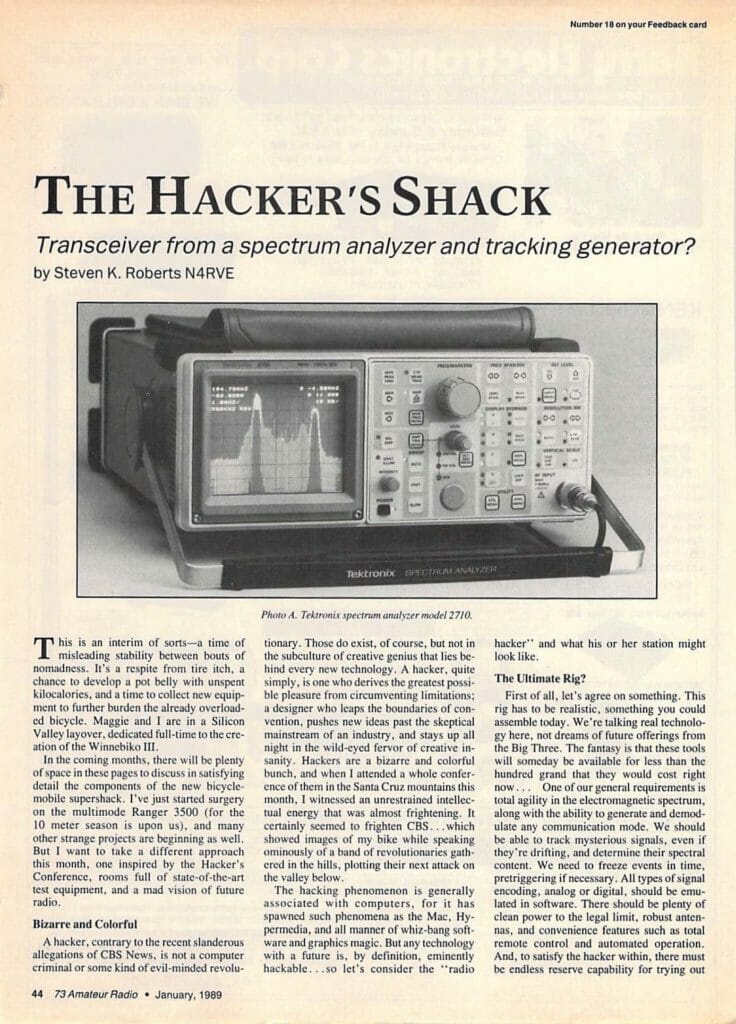

One of the least expensive spectrum analyzers in this class also has some of the most interesting features. The Tektronix 2710 (see Photo A), covering the fairly modest range of 10 kHz to 1.8 GHz (most of their models go to 325 GHz), offers the interesting feature of demodulating any signal highlighted by the cursor, with AM, FM, and rasterized video the basic options. What if we take one of these analyzers and give it a high-gain tunable front end, a product detector, and a GPIB interface cable to a host computer? Do we have a passable receiver?

To find out, I spoke with a few Tek engineers, and sure enough, it’s not a mad idea at all. In fact, Stan W7NI and Ken N6RO have dreams of making an all-Tektronix QSO between Portland and San Francisco using only off-the-shelf test equipment. The transmitter? How about a tracking generator that follows the spectrum analyzer’s sweep, locked on frequency by setting the instrument to zero span during a QSO? I’ve watched the machine handle video, 2 meter FM, and AM broadcast with equal felicity. You just set the cursor to an interesting peak or a specific frequency and tell it to demodulate to a built-in speaker or the screen. All bands, all modes, any bandwidth, computer control, graphic user interface… not bad for $10,000!

Once a true hacker starts thinking like this and ignoring price, things rapidly get out of hand. By the time we add a broadband kilowatt linear, a full-size log periodic along with other appropriate antennas, and full remote control of the whole system via laptop computer and 9600-baud TNC… we have a pretty hard-core ham station.

A License to Tinker

In reality, of course, commercial spectrum analyzers are not optimized to perform as receivers. There are many features we have come to expect in communications gear, including IF passband tuning, and so on. But I suggest this not-entirely absurd concept to make a point: we’ve grown so accustomed to buying special-purpose boxes to handle the essence of our hobby that the original spirit of ham radio has become almost vestigial, present only in the hard-core cadre of wizards and inventors who keep bringing us new toys.

It’s a dangerous pattern. I’ve met a number of packeteers, for example, who really don’t know what’s going through those wires between computer, TNC, and HT, other than something vaguely defined as “data.” While there’s a lot to be said for a turnkey radio data communications technology available to the masses (I’m all for it), we hams carry a license to tinker. Even though this hardly constitutes an obligation, it sure as hell is a pleasure… and as the average intelligence and education of the American human slowly falls, we find ourselves in the position of being the only ones outside the engineering labs who can actually make electronics work. That the designers among us are on the decline, I find disturbing.

The energy at the Hackers’ conference typified the spirit that should appear in the top 1-2% of ham radio operators: a mad, almost obsessive desire to build new systems (or make the old ones perform beyond the dreams of their creators). If this touches something within you, by all means… go for it!

Radical Oscilloscopes

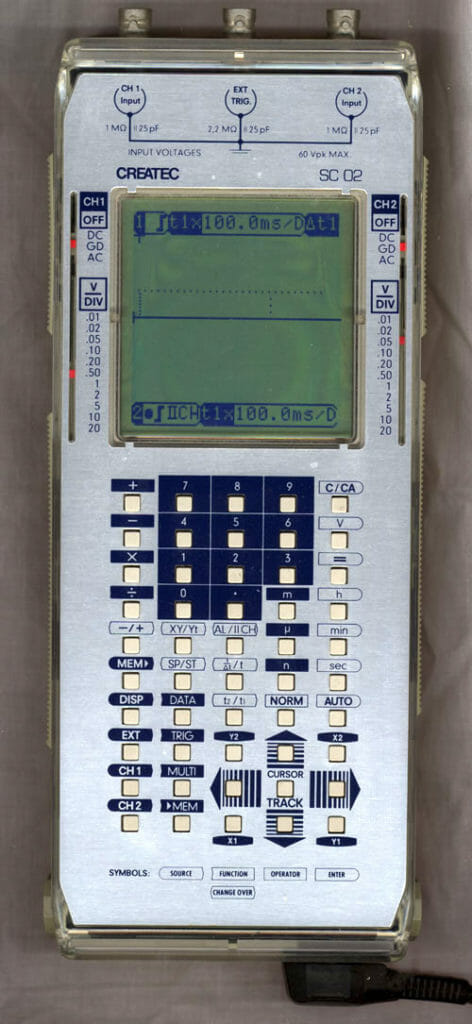

All this talk of test equipment reminds me: a few months back in these pages, I lamented that I carry no oscilloscope on the bike. That has finally changed. There are too many situations where the complexities of the system demand something a little more capable than a logic probe and multimeter.

The Createc SC02, shown in Photo B, is a West German marvel that packages, in less than 2 pounds, a complete dual-channel 20 MHz storage scope with 46 waveform memories. It can perform calculations between the incoming channels, or between either of them and any stored waveform. It has four cursors per channel, with digital read-out of their relative time and amplitude values. Ten “setup memories” allow you to recover weird configurations, and the 50-key keyboard lets you define every conceivable scope parameter with a structured command language. There is even a multimeter mode, which is more exciting than it sounds: a replica of the waveform is displayed in the lower right corner while the bulk of the screen presents a constantly updated table of peak-to-peak, zero-to-peak, average, RMS, period, and frequency… complete with calculated maximum error percentages based on the position of attenuators and various internal factors!

This unit is quite a departure from traditional oscilloscope designs, and the company is introducing a model early in 1989 that carries the concept to its logical conclusion: an optically-isolated RS-232 link will allow the SC04 to serve as a data-acquisition front end for digital signal processing, QC, or any other “smart instrumentation” application.

Power for the scope is provided through an external cable that carries +5 and +/-12, power easily derived from the existing switching supplies on the bike. I also carry a small AC supply for extended sieges at a bench, such as the one that’s going on now. Interestingly, this little unit is so comfortable to operate and so easy on the eyes that I’m finding it preferable to traditional lab scopes, except in those rare cases when 20 MHz simply isn’t enough bandwidth.

In next month’s installment, we should have a look at an important part of the new bicycle-mobile ham shack, the Ranger 3500 10 meter rig. Until then, cheers from somewhere in the electromagnetic spectrum!

You must be logged in to post a comment.