The Micro’s Environment

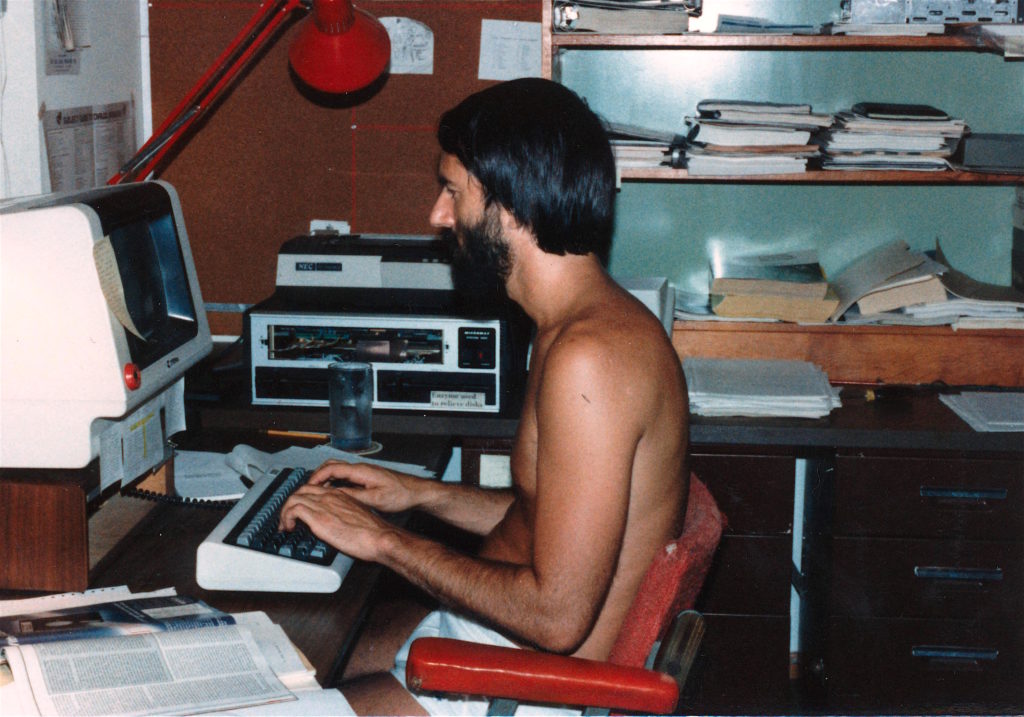

My on-the-road column about dealing with personal computers continues with a piece on reality. Photo above is the author at the Multibus base-office machine back in Ohio.

by Steven K. Roberts

Information Today

January, 1984

In this, the second part of our series on microcomputers, I think it would be appropriate to spend some time talking about the environmental requirements of the little beasts — before we become too involved in their operation. After all, the latter is quite dependent on the former. A machine treated with chronic disrespect can become so unreliable that it ends up, in a classic misplacement of blame, being viciously denounced as “garbage”’ by its users.

This is unfortunate, yet all too common. In researching a recent book on small system management, I visited many micro installations and was shocked to find the machines dirty, in static-prone environments, and sometimes even overheated from the obstruction of their ventilation slots by (of all things) floppy disks. These same machines were often the sole repositories of their owner’s critical data — which, in a shocking number of cases, were not even protected by backup files.

Most of this can be prevented through the application of some basic principles of computer care. Let’s look at a few.

Power

That innocent-looking power cord entering the back of most computer cabinets can be a veritable superhighway of noise propagation. The electricity provided by the utility company begins its trip from the plant quite cleanly, but can become profoundly corrupted in the process of making its way to your computer. Heavy equipment down the block, a photocopier on the same circuit, a squirrel dying on the power lines, lightning — all can turn that smooth, friendly sine wave into a nightmare of glitches, spikes, brownouts, drops, surges, and hash — with wild and unpredictable effects on your system. All of this is complicated by the fact that most such disturbances are random and infrequent, making it quite difficult to track them down.

Since you can’t always solve this problem at its source, the first approach to power-line noise immunity is the purchase of a good surge protector. Depending on the severity of your problems, you can go much further — up to a completely isolated uninterruptible power system if your application is critical enough.

Static

Another problem of an electrical nature can manifest itself just as brutally, and just as mysteriously. It can reduce normally staid executives to timorous folk who discharge themselves to a light switch and then tiptoe across the room to nervously touch the computer. This curious behavior results from too many devastating experiences with static.

The problem with static is that it produces disturbances of thousands of volts. When you consider that the computer’s circuitry handles signals in the 0-5 volt range, it’s easy to see how even a fraction of a static discharge can, in the wrong place, wreak havoc.

The solution? Keep the humidity above about 40%, and avoid using those synthetic carpets that make every handshake a shocking experience. There are sprays for the carpet that can marginally improve performance, but if you are having a real problem, an antistatic mat will be a much better investment.

Heat

Much ado is made by computer marketers of the fact that the machines draw very little power. “Less than a 40-watt light bulb,” you might hear, and this is quite true.

But if you put a 40-watt light bulb in a sealed box, you have a very effective oven (one popular child’s toy operates on this principle). Computers can cook themselves in short order, so to speak, if they are not allowed proper ventilation. Sometimes there’s little you can do about the problem — your machine may have been designed poorly. This was the case with a CRT terminal that I once managed to tolerate somehow. I finally cut slots in its cabinet with a saber saw to stop it from destroying itself every month or so.

But you can easily prevent the common forms of abuse. Ventilation slots must be given good clearance and a free flow of fresh air. Yes, as I noted in the introduction, some people actually keep a stack of disks on top of a terminal or system cabinet — right over the openings. This can not only kill the machine but warp the disks as well.

A number of systems come equipped with fans. These are a mixed blessing: the moving air keeps things cool, but it also deposits dirt all over the inside of the system. That problem can be solved with a filter, but that can clog and make things worse than they would have been with simple slots. (Nothing is free.) Regular maintenance is the key here.

Media care

This is the big one. All the foregoing notwithstanding, computers can take awesome abuse and keep right on chugging. (Mine lives full-time on a recumbent bicycle and thus experiences temperature extremes, rain, dirt, and daily vibration as I travel around the country. It still works.)

But computers gain much of their charming mystery through the hosting of your critical data in a form that is in no way amenable to human senses. In most installations, this takes the form of floppy disks. Sensitive to magnetic fields, heat, fingerprints, cigarette smoke, cat hair, bending, compression, spilled cola, invisible dust, and telephone bells, the floppy is one of those necessary evils that persists in the computer industry despite inspired efforts to come up with something better (but still cheap). The net effect is the need for something approaching obsessive-compulsive behavior on the part of the computer user.

Disk handling and storage procedures are simple, obvious, and usually overlooked. Simply protect them from all the evils noted above, and you’ll be fine. (Blatant book plug: my recent publication, The Complete Guide to Microsystem Management, Prentice-Hall, contains a full chapter on the subject of system and media care.)

Closing notes

In a column-length story, it is impossible to address all the considerations involved in the physical care of a computer. All I have really expected to communicate here is some suggestion of the problem’s severity, and the general kinds of steps necessary to prevent it. These are some of the things often glossed over by computer store personnel, for a full litany on the potential horrors would hardly encourage a purchase.

In actuality, of course, all this is a bit cynical. Computer systems are usually quite reliable (yes, amazingly, even the diskettes). Problems develop, more often than not, from a general lack of respect for the machine. This can become circular: humans maltreat system, system gets flaky, humans abuse system in contempt, system breaks down, humans dump system at a tragic loss and buy something more reliable. And the process begins anew.

Preventing this calls for little more than a reasonable common-sense understanding of the machine and adherence to a few basic rules of computer care. This effort will pay off many times over and make the whole experience of owning a computer more pleasant for both you and the machine.

Steven K. Roberts is the author of numerous magazine articles, as well as three books about microcomputer-related subjects. He travels full-time on a word-processor-equipped recumbent bicycle and communicates with his publishers via the CompuServe network.

Steve can be reached at CompuServe ID#70007,362 or via postage mail care of this publication.

You must be logged in to post a comment.