Trouble in Paradise

Computing Across America, Chapter 18

by Steven K. Roberts

Key West, Florida

January 3, 1984

Where are you coming from?

— Question heard all down the coast, contrasting sharply with the usual “Where are you going?”

It had been a hard day. I was southbound at the 28th parallel, searching for a place to sleep. This was a land of classy homes and private beaches, and for some stubborn reason I had been reluctant to cross over to busy US1 just for the motels. I was obsessed with being near the shore, even if there were few points of public access.

But I was tiring, and when I finally saw a small lazy motel a few miles north of Sebastian Inlet, I coasted into the parking lot with a sense of relief. There were only two cars there.

I removed my helmet, stretched, and walked into the office with a cheery hello. “Long day,” I said with exaggerated exhaustion. “I just rode from Titusville. How much for a— “

“Oh, I’m sorry sir,” interrupted an ample middle-aged woman, looking at me nervously as a wide-eyed little girl of about eight peeked around her. “I just rented the last one — in fact, I was just now getting ready to go hang up the NO VACANCY sign.” She rooted around behind the counter for a moment and held the placard up for me to see. Sure enough. It said NO VACANCY.

“Amazing how many people arrive on foot these days,” I observed, gesturing out the window to the nearly empty parking lot.

She drew herself up in a defensive huff. “Well, I certainly don’t know where they all went!”

“Right.” As the woman followed from a safe distance, I stepped outside, refastened my sweaty helmet, and climbed aboard.

“Uh, I have to ask,” she said from the safety of the doorway. “How do you steer that?”

I demonstrated without a word, then started to pull away. After I had gone about six feet, she suddenly raised her hand to her cheek and cried, “Ooooh, you pedal it! Wait… I thought it was a motorcycle!”

“That’s right,” I called back to her. “It’s a bicycle. Appearances sure can be deceiving, can’t they?” I accelerated toward the road. I had no interest in doing business with her — and it was eighteen more miles before I found an unbigoted place to stay.

The experience was sobering. I rode past Sebastian Inlet and on toward Vero Beach, strangely depressed. I had always been reasonably removed from racial matters — having had enough friends of various backgrounds over the years to defuse most of the stereotypes. I’ve laughed at my share of ethnic jokes, of course, but never with malice.

The motel encounter had nothing to do with race, but it had a lot to do with bigotry: the “stubborn and complete intolerance of any creed, belief, or opinion that differs from one’s own.” The woman thought me a biker and wanted nothing to do with me, even lying and turning down business to keep it that way. Part of me could chalk it up to ignorance; the rest fumed at being judged according to somebody’s preconceived notions. I had a sudden empathy for what non-white minorities face daily — no wonder they get angry.

But I was looking ahead to a place that could cast me into the opposite role: Miami. I had heard so much about the horrors of this troubled city that I visualized a giant crime-ridden ghetto stalked by strung-out blacks and hostile Cubans. All with Saturday night specials. Would I be like that woman in the motel, making poisonous assumptions on the basis of appearance? I had to be honest: being a vulnerable white guy on a flashy recumbent made me nervous.

I witnessed the same illness in another form over the next couple of days as I pedaled down A1A through mile after mile of ritzy oceanfront homes. Riding Florida’s “Gold Coast” was like riffling through an issue of Architectural Digest, the names on the mailboxes doubtless a Who’s Who of Success itself.

But it was surprisingly unfriendly. I would coast happily along a pretty road and smile at a retired couple; they would grab each other’s arms and watch without making eye contact until I was safely out of purse-snatching range. I would call “Good morning!” to a Mercedes driver at a stop light; he would peer at the bike as a curiosity and then self-consciously fix his gaze straight ahead. One old couple even locked their car doors as I pulled alongside, seeing my sweaty T-shirt and worn packs as evidence of lowlife tendencies.

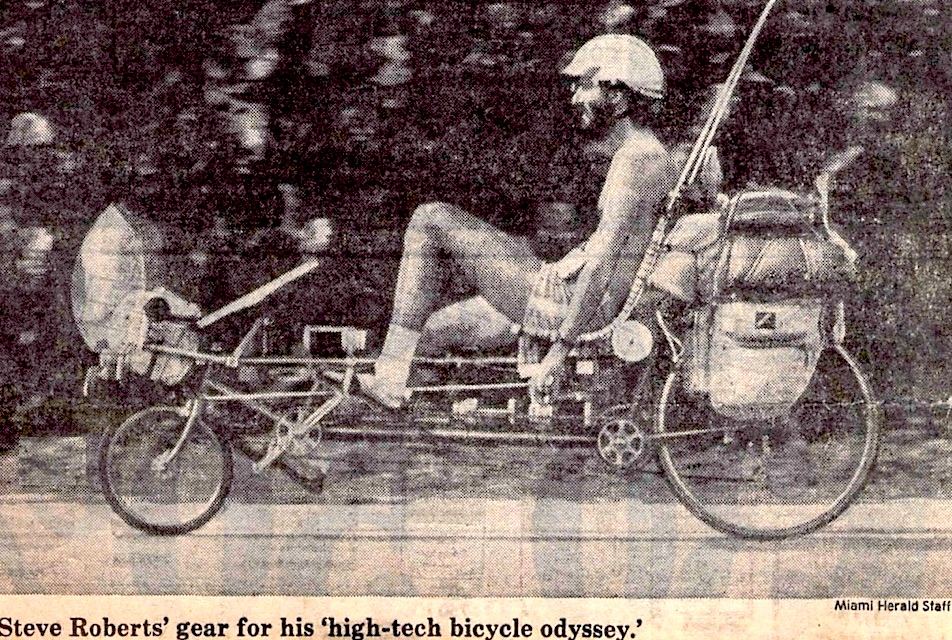

Of course: I am a drifter, a wanderer, a bum. Many of these people would draw no clues from the high-tech accoutrements of my journey, for I was obviously just pedaling around looking for a dry place to lay down my sleeping bag. I may have looked interesting, but certainly not successful.

But what is success, anyway? Bob Widlar, a legend of Silicon Valley, haunted Mexican beaches for years and lived like a “bum” while designing some of the world’s most advanced integrated circuits. Shel Silverstein, looking every bit the degenerate, sits in the murky shadows of a Key West bar and writes brilliant children’s stories. James Michener, with lifetime book royalties estimated over $100 million, lives the spartan lifestyle of a Quaker.

Yes, it’s possible to be wildly successful without a three-piece suit, a flashy car, and beachfront condominium. If any formula at all can be hung upon the notion of success, it is the ratio of all you put out (work, sweat, creative energy, suffering, time, etc.) to all you get back (pleasure, freedom, satisfaction, learning, sex, and oh yes — money).

I rode on to Boca Raton, where people finally started to become friendlier. Perhaps it was the high-tech influence of IBM and other firms — the residents drawing intriguing inferences from the bike and solar panels. Perhaps it was just a lucky change in the character of my chance encounters. Whatever the case, I cruised along the town’s excellent bike path, stopping here and there to chat, even riding for a mile or two with a trio of female bikers wearing dangerously alluring <pang> clothes and Sony Walkmans.

More <pangs>. I was enroute to Hollywood and had to hurry, like a fool, through Fort Lauderdale. Hurrying through Fort Lauderdale. This is one of the Great Regrets of my journey — zipping through a sea of tanned flesh, the very substance of my Florida fantasies, zipping along with the tireless power of adrenalin so that I could make it to Hollywood, of all places, by dark. I rode down the Fort Lickerdale strip rubbemeckin’ left and right, awestruck. If all the bikinis in town were sewn together, they might make one nice set of lightweight curtains.

The hotels were tall and parallel with one another, raising fantasies of open windows and telescopes. The women were long and brown. The bars were hopping with Almost-New-Year’s-Eve parties. And I didn’t even stop; I hit all the traffic lights on the green.

Sigh.

So what was so exciting about Hollywood, a place where more people speak Quebec French than Florida English? Hollywood, a placid place of retired snowbirds and sedate restaurants? Easy. It was a relaxed three-day New Year’s layover with Frank Feczko and his family. Yup, the same Frank — that crazy Hungarian from Pittsburgh who was trying to sell my house in Columbus, that balding friend of easy grins who had attempted to make me look at this trip logically even while urging me on. Good ol’ Frank.

The journey was on hold, in a way, even though I cruised lazily up and down the Broadwalk on the unpacked bike in a holiday promenade of people-watchers. This didn’t feel like a visit: Frank had been so much a part of my Ohio life that despite the ocean rumbling just outside the sliding doors, I seemed to be dropping in on my neighbor.

New Year’s Eve. I met Barbara online for a spirited exchange of suggestive giddiness, our Key West rendezvous only days away. I sat afterwards in the quiet condo bedroom, munching stale malted milk balls that were given to me back in Chapter 10 — prompting me to call redheaded Mary of Ohiopyle with a few verbal New Year’s kisses. My neighborhood was getting pretty big.

I made the death-defying plunge into Miami early on New Year’s Day. I figured everybody would be sleeping it off — or at least too hung-over to harass me. Such a thing is fear: from the mountain of bad press the city had received, I was prepared for the worst. I would need all available luck and skill to emerge from the city unscathed and continue down Highway 1 to paradise.

Uh-oh. Cubans. I steeled myself. I was stuck at a red light in the south end of Miami Beach, and there was too much cross traffic for me to escape. Three dark Cuban men in their early twenties stepped off the curb and headed my way.

One reached in his shoulder bag and pulled out a camera. Another just stood there, checking out the machine with a slowly broadening grin. The third pumped my hand and cried, “Haaay, muy bueno beautiful, man!”

Throughout the city, it was the same feeling. People smiled and waved; one guy stopped me and held out a copy of the Miami Herald story (“Writer Pedals His Home Computer”) with a pen clipped to it for my autograph. I spent a delightful half-hour with the jolly round black proprietor of DJ’s Cycles in South Miami — he offered to trade lifestyles right there on the spot and gave me a reflectorized leg band as a souvenir. I cruised easily through town and was out in the swamps before I knew it.

It was an old lesson learned afresh. I had been as wrong about “all Cubans” as the motel woman had been about “all people wearing helmets.” It was with relief and satisfaction that I knocked down the twenty-seven desolate miles between Homestead and Key Largo — hardly even minding the cherry bomb that some redneck in a passing camper tossed at me.

At last! The Keys! Paradise. Scuba diving, lush greenery, probably even parrots. Orchids. I was scared to death of the forty-two narrow bridges I had heard about (one of them seven miles long), but hey — what the hell? No reality could be as bad as my fears about Miami. I rode along with a smile, waving at everyone who looked my way. I was only 110 miles from the southernmost point in the US. Some guys loitering in front of a Key Largo liquor store hooted at me, and I waved at them too.

Then they came after me. “I’m gonna steal that bike!” one cried, and they piled into a noisy old GTO, peeling out of the parking lot before even getting their doors slammed. I heard them roar through the gears as they came up behind me, not moving over, not even staying on the road… aiming directly at me in a deliberate collision course.

Shit! I jerked the bike to the right, sliding for a sickening moment in the loose gravel, then bounced violently into the ditch and broke a fairing strut. The car blasted by in a cloud of dust, and I watched in disbelief as a passenger leaned out of the window as far as his waist and swung a red electric guitar at me by the neck. It could have been a real Fender-bender, but he missed by about six inches.

I was stunned. Frightened. Alone. Disillusioned. I expected them to return; I was shaking in fear of the next encounter. I pulled into the first motel I came to — $65, more than I could afford. With misgivings I returned to the highway, seriously considering the purchase of a handgun and already thinking about an easy-access waterproof holster. As lights started twinkling on in the stunning purple-orange of sunset, I stopped at the first campground and hid out for the night. The last of the spectacular sunset rippled in deep hues across the island-pocked waters of Florida Bay, and I stood, drinking my second beer, slowly calming myself with the reminder that there are jerks everywhere — isolated jerks of no particular race or region. It’s inevitable that I will encounter a few now and again.

So why let the bastards ruin my day?

A more cheerful footnote to this story is the vacationing couple from Maine I met the next morning in a nearby shopping center. They were Sandy and Betsy Alexander — the former as crusty and taciturn as an old New England sailor; the latter radiating enough warmth to melt the ice of a harsh Maine coastal winter. They had been together forever.

I told them about the red guitar incident. Sandy shook his head and frowned; Betsy grew indignant and said, “Well honey, are you carrying a St. Christopher medal?”

“Uh, well, I’m not Catholic — ” I began, wanting to change the subject.

“That doesn’t matter! Here… wait… I want you to have this.” She fished in her purse and removed from her keychain a well-worn brass medal, almost unreadable from decades of handing. “I’ve carried this for twenty-seven years,” she said.

“Oh, I couldn’t possibly — “

“Shush. I want you to have it. I can get another.”

I was moved almost to tears. Goose bumps prickled the flesh of my arms and legs. Twenty-seven years: ever since I was four, Betsy Alexander had carried this medal with fervent belief in its power. Now it was to travel with me through the unknown miles that lay ahead. It seemed to glow, not from its iconographic content but from the depth of her faith and the love that accompanied the gift.

The worn and bent St. Christopher medal has stayed with me across the land, a constant reminder that love and hope are infinitely more powerful than the occasional nastiness of bad boys. Call it superstition, God, or the power of positive thinking. Call it magic.

Call it whatever you like.

Onward I went, down one of the longest dead-end roads in the world. The sense of isolation from the mainland competed with the madness of a perpetual party. Everyone seemed to experience the “out-of-town syndrome” here — littering, shouting, and driving more wildly with each drained beer can.

The red guitar had tuned my senses, keeping my nerves taut as I fretted over the possibility of a repeat performance. I no longer trusted drivers, and the two-day ride was a mishmash of brief images held together by a nervousness that never quite abated. For 108 miles I watched every car, every truck, every boat-toting land yacht. There were bits of a bike path here and there to tempt me away from the road, but they were rocky and strewn with glass, dead-ending or veering back into the narrow highway without warning.

I was delighted to discover, however, that within the past year all forty-two bridges had been replaced. Bike lanes! The bridges were now the best part of the highway, but seeing the old ones I could understand the warnings: there wasn’t enough room for two vehicles and a bicycle to exist side by side. Many a cyclist’s ghost haunted those narrow concrete-walled deathtraps, pedaling invisibly among fishermen rich and poor as they stood along the railings in private rituals of sport or survival.

On and on. The smells of fish, sewage, tropical perfumes, dank swamp, exhaust, fast food, salty air and salty sweat all blended as I pedaled numbly, taking roadside snapshots with my brain. Scuba shops, bait places, liquor stores, key lime pie. A QUAHOG license plate. Secluded estates of understated opulence, the filthy kids and abandoned cars of poverty, motley tourists by the thousands. Hot sun, southern tans, northern burns, sparkling water. And boats, everywhere boats — from classy cruisers to rotted hulks abandoned on the shores, from car-top sailboards to racing yachts.

Little roads disappeared into the mangroves, sometimes offering a glimpse of sea at the end, sometimes receding into the distance as if there were actually somewhere to go out there. Riding into the ocean, island after island, bridge after bridge, I soon realized I was closer to Cuba than to Miami.

The miles went on, yet there were no clues about Key West itself, not in the little resorts, the houses on stilts, the billboards, the fishermen, the sky. The end of the highway was a mystery out there on the blue horizon, a place of both dark terror and the bright promise of island paradise.

I hit my 3,000-mile mark on Summerland Key, then smiled for the first time in two days as a carload of laughing young women passed. They sported a yellow bumper sticker:

You must be logged in to post a comment.