The Microship Puget Sound Mini Expedition

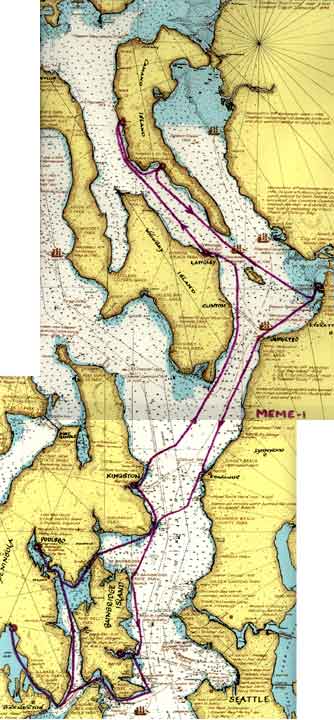

This piece was written during the 132-mile MEME — the Microship Experimental Mini-Expedition, launched a few days after 9/11/2001. It was a strange time, but the boat performed beautifully.

by Steven K. Roberts

October 14, 2001

I’m perched in Microship Wordplay, trapped in a Poulsbo marina by a small craft advisory, slowly adapting to life aboard this tiny craft as we near the end of a 2-week mini-expedition…

Suddenly my whole perception of the Microship has changed. The mercifully short TO-DO list that has fallen out of this first real test sail includes nothing fundamental… a few essential leak fixes inspired by a grim rainy layover in Everett Harbor, better gear organization, some cockpit niceties, an improved electric thruster (I can pedal faster than I can cruise with a trolling motor drawing about 30 amps!). But so far there are no “deal-breakers”: she sails dry, points high, and loves to fly. Even the dreaded on-water bivouac mode, though spartan in the extreme, became manageable once I got used to viewing cockpit clutter as a 3-D version of one of those sliding-tile puzzles and stopped expecting convenience.

The whole pace of life changes afloat. Projects are clearly defined and appear in singles or small groups, not as mutually dependent tangled threads with the collective flavor of Deadly Embrace and no sense of closure. Our days are ordered by current tables, NOAA weather broadcasts, random encounters, and the spacing of shore facilities… not by the numbing overload of life in the lab. It’s all an illusion, of course. I just got a book contract for Inside Microship, to be published next year by O’Reilly & Associates [note: the book project was aborted]. This is good, though if I understand the situation correctly, now I actually have to WRITE the thing.

But that’s all abstract at the moment, for I’m sitting in my boat with a laptop, living this 9-year-old dream for the first time, thunking my rubrail gently against a dock at the head of Liberty Bay as we catch eddies of the 25-knot winds frothing open water not so far away. We tried to leave yesterday, rising at 0600 to zoom downwind in time for a favorable current in Agate Passage. We poked our noses around Point Bolin only to get hammered… hard… driven back to the marina in a brutal upwind death march that took four times as long as the outward leg. All part of the amusement, I suppose. By the time we would normally be caffeinated and slouched in front of the day’s email, we had already tasted fear, slammed into Force 6 winds, pedal-tacked frantically off a lee shore, and flown deeply reefed across a wind-whipped watertop sparkling in the morning sunlight of a Pacific Northwest autumn day.

And so, things have become clearer. A few fixes and enhancements, solar array thermal retrofit and mounting… and then it’s time to conjure the console system that was originally (I thought) the point of all this. The good news is that we have spent enough years fiddling around with the nautical substrate that we can simply acquire much of the gizmology we thought we were going to have to invent from scratch… substantially trimming the task list and even eliminating entire computers (one of the best things to do with them, I have discovered). The biggest single project remaining appears to be software, though I won’t admit that when wrestling with console packaging.

Natasha has been remarkable through all this, and I’m not just talking about her ability to survive the toxic knuckle-busting rigors of boatbuilding and whip up fresh albacore sandwiches at the dock. I was particularly impressed this past Sunday, when we left Eagle Harbor on Bainbridge Island bound for Dyes Inlet. We bid farewell to friends new and old, cast off our lines, and sailed in tandem past yachts of all flavors, the manicured lawns of waterfront homes, and the Seattle Ferry loading up for a run. The boats flashed in the sun, hers bright red with purple Sunbrella, mine Hatteras off-white with enough Bristol gewgaws to stop old salts in their tracks and crinkle their faces with kidlike grins. A perfect day. But when we rounded the last mark and turned south in Puget Sound, the full force of the 25 knot wind hit us from the port quarter, and never have I had such a frantic broad reach. Surfing, fighting weather helm to prevent broaching, I watched constantly over my left shoulder to time my response to the waves… some tall enough to momentarily block my view of Seattle. I raced past Blakely Rock and toward Restoration Point, watching muscular seas toss me about and then break on the shoals a hundred yards to leeward… glancing every few seconds at the GPS to see how much more of this rather TOO exciting sail I would have to endure. I wanted to reef, but would have to head up to take the load off the rig enough to furl.

My real worry, however, was Natasha. She’s never done this before.

Perhaps because she didn’t know enough to be scared, she handled it beautifully, though at one point I saw her head up toward Seattle and had the mad thought that she was jumping ship, figuratively speaking. But she was just giving herself some sea room off the wicked lee shore: instead of responding to each wave as I was with her decreasingly responsive rudder (hydraulic leak), she was grabbing a load of slack in one big gulp. Good move.

Tales of the MEME

The Mini-Expedition has now ended, and it diverged considerably from the original plan (mostly due to weather this late in the season). After a blur of last-minute work that is painful to recall and would be even worse to write about, we hauled the boats a mile down the road to the local launch ramp. This was the first test: how would the landing gear perform? Mine, in particular, have consumed entirely too large a percentage of this project’s overburdened budget, and the past few months of lab work have included a complete re-rigging of the deployment system — replacing all the original line with turnbuckle-tensioned 1/8″ black-jacketed 7×19 stainless wire rope with swaged-on thimbles, as well as a geometry-shift system to accommodate reverse and a new scheme for tensioning the steering wire inspired by old 3-speed bicycle brake barrel adjusters. I sorta decided somewhere in there that this is the last chance… if the gear still have intractable problems, I’ll switch to the system on Tasha’s boat (not something I would want to do: the job itself would be a nightmare and I’d hate to give up the elegance of lever-deployment… and besides, they’re beautiful). So the good news here is that the mile to the launch was absolutely uneventful, even with a few rough spots and encounters with gravel. Gravity was intense, but we can’t blame the wheels for that; I just have too much stuff.

The basic trade-off between the two design approaches is that mine are turnkey and profoundly geeky, with aircraft-grade fabrication and massive engineering geared to convenient and efficient operation. They also took nearly two years to build, and are easily the most expensive part of my boat. Tasha’s, on the other hand, are dead-simple, rock-solid, came together quickly, and handle much heavier abuse without threatening to fail… but they are far more troublesome to use (she gets wet and takes 5-10 minutes to accomplish what I do by pulling four levers from the cockpit, along with a cocky grin and the words, “you ready?”). In a serious crash, hers would break fiberglass and mine would break hardware. But I’d much rather haul hers down a rough road, and in Dyes Inlet at Greg Jacobs’ house I left mine on a mooring buoy while she easily beached — the stones were just too big. I hate trade-offs, don’t you?

So with the invaluable muscular assistance of Tasha’s mendicant philosopher pal Nick Routledge and resident wizard Ned Konz, we made our way to the launch and pushed off. Suddenly it all became surreal, as this was not to be another little afternoon test sail like the first four launches — we were heading out into unknown conditions for two weeks. This is the first reality check of any consequence, 4.5 years since the moment of radical re-thinking that spelled the end of the Hogfish era and the move to this design. Oddly, the stress level was low, but the sense of delicious madness was profound and the whole experience unspeakably beautiful… drifting quietly down the west shore of our island, seeing it at last from the perspective that lured us here in the first place.

The last leg of this first day was a short windless crossing of Elger Bay after rounding the point at the State Park, and we decided to try our electric thrusters. In short, they were a bit disappointing… only moving the boats at about 3 knots instead of the estimated 5.5. Part of the problem may be undersized wire from the battery 8 feet away (via a temporary switch); the cable gets a bit warm, which means significant I²R loss. The round fiberglass shafts also ventilate considerably, and I question the prop pitch and speed in this application. This will call for a bit of research… a lot of work has gone into the controller end (which, like many things, was not on board for this trip), and it would be a shame to skimp on the business end.

The first stop, reached well after dark with navlights and GPS backlight aglow, was Rick Wesley’s waterfront house with its huge flight of steep steps and a tent on the bulkhead. We made the rafted boatlets fast to his mooring buoy and dinghied to shore… not a convenient mode, given the need to schlep gear, but the only choice in this environment where the tidal range includes the bulkhead itself. Again, surreal… I climbed the steps in the morning and gazed down in wonderment at the delicate sunlit boats on their shared mooring: such a different perspective from the workstand under fluorescents. Tiny little buggers…

Their diminutive scale became more apparent the next day. We headed south between Camano and Whidbey Islands, the wind gradually becoming useful, at last emerging into more open water to pass by Gedney Island on a broad reach to Everett. This was our first chance to get slapped a bit by waves and gusts, share the water with the big boys and those omnipresent wake-generating noisy powerboats, depend on the GPS to find an entrance buoy, pass a Coast Guard cutter on high alert, drift past a Navy base, and actually <gulp> enter a marina. That turned out to be a smooth process, and they were kind enough to let us share a slip and pay by aggregate length. What we didn’t know is that we’d be stuck there for the next three days.

Relentless heavy rain and high winds are profoundly demotivating when you’re in camping mode, and we hung around, dejected, making far too many long walks to the marine emporiums of West, Harbor, and Popeye’s. The goal became a vague melange of leak elimination and staying warm, and I compiled the first to-do list of the trip: places that have to be sealed to prevent rain from converting an already minimal sleeping environment into a miserable one. A friendly couple on a quirky 50-foot homebrew ketch took us in, so we did have two dry nights…

When conditions finally mellowed, we rose pre-dawn to ride the flood current south, and made Fay Bainbridge State Park at slack pretty much as planned. Unfortunately, despite the information in two of our four on-board references, the launch ramp had been removed a few years ago and the driftwood-strewn lee shore was not inviting even with a Cascadia Marine Trail campsite. Thus began the first “death march” of the adventure… a long, exhausted pedal against the ebb down the east side of Bainbridge Island to Eagle Harbor.

We parked at last in the delightful Harbour Marina (with its superb pub) and schlepped our gear to the home of Charlie Faddis. Now this was more the flavor of proper technomadics… hanging out with brilliant friends and partying with the live-aboards, not huddling in separate boats, miserable in the rain, making lists of leaks. Life improved.

Of course, the sunny morning that we left propelled us into that gonzo wave-toss’d reach down to the lee of the island… yikes! I felt the stirrings of fear, got a much better sense of the rigging stresses involved, and started worrying about solar array windage. But after this dose of adrenaline and harsh reminder of mortality, the expedition became a sweet blur — connecting the dots of friends and marinas, tweaking our plans daily as weather and random delays imposed scheduling constraints far more immediate than the normal influences of deadlines and calendar coordination. Through the locks and into the Seattle lakes to pedal with Michael Lampi and visit other waterborne pals? Up to Port Townsend for the Kinetic Sculpture Race, with a stop at Port Ludlow enroute to visit wireless data wizard Dan Withers? Looping back to Camano Island via Deception Pass, or maybe even Anacortes? None of those happened: delayed a day here, a day there, hemmed in by winds as the season turned, we soon realized that we’d do well to simply claw our way back upwind and get to work on the next phase.

We left multihull maven Greg Jacobs’ place in Silverdale, backtracked past Bremerton, than had a long pedaling slog up the west side of Bainbridge and into the trap of Poulsbo. Not realizing the implications of a northwest/southeast bay coupled with a southwest/northeast exit passage in an environment that offers a steady diet of northerlies punctuated by occasional southerlies (got all that?), we docked at the marina for what was to be a one-nighter in a cute town. Alas, this place had ludicrous pricing policies… while the other four marinas on the trip charged us by the aggregate foot, the Port of Poulsbo Marina imposed a $15 minimum per boat. This had us paying $30/night to dock two canoes, exactly the same fee for two coffins-worth of sleep space as the 60-foot Chris Craft Constellation yacht gleaming lavishly on the end tie. No attempt to point out the absurdity changed their minds.

We were stuck in the otherwise delightful Poulsbo for $90 worth of dock time, making daily visits to Prototek, hanging out with a colorful albacore fisherman, and listening every few hours to the NOAA weather broadcast. It kept prattling endlessly about small craft advisories, with wind gusts to 30 knots and other unpleasantries. As I mentioned at the beginning, we got impatient on a seductively sunny morning and took a shot at it — broad reaching 5 miles down the bay and into Agate Passage where we were slammed by a funneled northerly that, coupled with current in our favor, generated remarkably peaky little waves with their tops blown into long streamers. There wasn’t enough fetch for the seas to be a problem, but the wind stopped us in our tracks. I tried to fight it for a few minutes, pedaling hard, then a gust shoved my bow around and I went careening downwind while Tasha went bobbing off toward Bainbridge, wrestling on the foredeck with a jammed furler. It took almost four hours to battle our way back upwind to town.

We escaped eventually, of course, and made two back-to-back death marches into relentless northerlies to reach Kingston, then Langley… both pleasant villages with friendly marinas and well-stocked pubs. The final run to Camano Island, 9 easy miles scooting 4-5 knots in a rare southerly, dropped us at our local launch ramp by noon… where we wrapped the whole thing up with a grueling, gravity-defying 1-mile haul of our collective tonnage up the wheel-sucking beach, up a nasty hill, up a long road, up another killer hill… well, you get the idea. It’s due to the Roberts Law of Aquatic Gravitation: water collects in low places, so leaving is always harder than arriving.

That’s true in a metaphorical sense as well. During those 2 weeks at sea, magical at some times and brutally difficult at others, I barely thought about terrorists, geopolitics, deadlines, resource-extractors and developers raping our island, or any of the other psychic energy sinks of daily life. There’s an immediacy in sailing that captures the mind and soul, and small wonder some people never come back. Already, a few days later, I’m embroiled again in complexity… dreaming of the expedition to come and further refining the project to streamline the path from here to launch.

I’d like to devote the rest of this update to a few comments on equipment performance. But first, some data points…

Statistical Interlude

Microship Wordplay

Number of blocks: 42

Feet of line: 225 (plus 185′ of anchor webbing)

Hydraulic cylinders: 13

valves: 13

fittings: 128

tubing: 150′

Weight: about 900 pounds plus me

MEME-1 trip data

Total distance: 132 nautical miles

Longest day: 28 nm

Average day: 14.6 nm

Highest speed observed: 7.5 knots

Pedaling speed: 3.5 knots relaxed, 4+ pushing hard

Equipment Performance Observations

In general, things worked beautifully. The following commentary addresses individual subsystems and components….

The trimaran itself: Surprisingly good. The ride is drier than I expected with this low freeboard, even in rough conditions, and she points fairly high (much higher if I’m also pedaling). I can complete a tack in 90 degrees with pedal-assist, about 130 degrees without. The aka hinges creak somewhat, but it feels good — there is plenty of bow buoyancy and she’s generally “on her lines.” The wake is clean, as the sleek Wenonah Odyssey canoe hull and the two Fulmar amas slice cleanly through the water with minimal turbulence. Even at over 1,000 pounds all-up weight, the boat feels light on the water (but not on land!).

Sailing rig: Not bad at all. The WindRider rig roller-furls around the mast, and I added a double furling drum to control this reliably from the cockpit (my original single drum was terrible). I also added a decent outhaul and split vang, both of which lead back to cleats on the aft port aka. These make deployment and retrieval much easier, and the vang flattens out the sail on a run by lowering the boom. And the Ronstan traveler track on the arch, though seemingly too short to make much difference, gives me a very noticeable advantage when pinching (sailing close-hauled to windward). The only remaining problem is stepping/unstepping, and we’re working on tabernacle and hinge concepts to make this less painful.

Spinfin pedal drive unit: Spectacular. This turns out to be a key component of the boat, faster than the electric thruster. It’s always available with a quick flip of the deployment lever, and not only lets me cruise at about 3.5 knots but vastly improves windward sailing performance. For close-in maneuvering such as docking, the Spinfin is a lifesaver. Early in the trip, I had clunking problems on the port side, but they were simply the result of misalignment in the crankset, easily adjusted with the Tran-torques once I stopped and paid attention to the problem. Afterwards, the remaining miles were silky smooth. Tasha’s boat uses a Seacycle drive — it’s slower and has more static friction than the Spinfin, but was still reliable. With both of us pedaling without exertion for an hour, I tend to end up about a half mile ahead.

Electric thruster: Further refinement needed. Speeds here were lower than pedaling, which doesn’t make much sense… I suspect cable loss and ventilation problems. Still, the units were immensely helpful, allowing us to justify our monstrously heavy batteries by getting a beautiful lift upwind and against the current. Tasha used hers for at least 5-6 hours, rescuing her knees from certain demise; I put about an hour on mine.

Landing gear: Much better than expected. As I mentioned earlier, this has been a nightmarishly complex part of the system, and my confidence level was low. But there were no problems on this trip, which included about 2.5 miles of often-difficult road time. I’m seeing some corrosion in exposed bearings and stainless components of uncertain pedigree, as well as minor initial stretch of the new cables (easily adjusted out), but nothing serious as far as I can tell without disassembly. The forward units do splash on a close reach in choppy conditions, but the one time it happened I was overpowered anyway and didn’t mind the drag.

Hydraulics: Excellent. I had one leak, in a chain of adapters associated with a temporary cheap pressure-relief valve used for rudder kick-up (the stainless one I want is about $200, so I got a bronze junker for testing). The Clippard cylinders distinguished themselves with trouble-free operation and no signs of corrosion, and the new bleeder system involving 26 ports solved the air bubble problem perfectly. My working fluid is a 50-50 mix of propylene glycol and distilled water, with red food coloring added. I just elevated a solar shower and gravity fed this into the system after first purging it with tap water (hence the coloring; that told me when to quit).

Communications: Needs integration. For this trip, we depended on handhelds for boat-to-boat use, and they were way too fiddly. Every day we had to deal with battery charging, sealed bags, trying to hear each other, and avoiding the loss of expensive widgets overboard. The radios themselves are excellent (Motorola Talkabout FRS and Alinco dual-band HT), but for marine use, all essential communication tools have to be integrated and the handhelds reserved for the backpacks. My boat also has a Standard DSC-capable fixed-mount Marine VHF. In the long run, of course, all my comm gear will be built into the console and accessible via the crossbar network. The most amazing communication device that accompanied us on this trip was the Globalstar phone… reliable even without the external antenna, and my key lifeline to the outside world. This, too, will become part of the integrated system when the console is built.

Cockpit Utility and Sleep Facilities: Cramped and challenging, but possible. This is definitely “camping scale adventure,” not yachting. There are about a dozen leak points that need to be fixed, and the most fundamental lesson is that there is no room for stray gadgets, bags, and random stuff floating around the cockpit. Everything needs to be either integrated into the ship or given an unambiguous and accessible stowage spot. Sleeping is difficult for me with my 6’4″ height and lower back problems, but it works surprisingly well — the Therma-Rest mattress is highly effective, and it’s kept above the always-wet bilge by .5″ cross-tube matting we found in the McMaster-Carr catalog (more flexible and prettier than the tile system in the marine supply stores). The fabric dodger is wonderful, though the side windows need work; the polycarbonate windshield is crystal clear, though I inadvertently disabled its essential fold-down feature with the cowling solar panel mounting.

Pack System: Effective but hard to use. Almost everything is stored in Cascade Designs dry bags, which are excellent and reliable… but I only have the tiny forward and aft compartments in the canoe hull, accessed through hatches. There’s just not much space, so doing anything involves a bit of a juggling act in cramped quarters. On this trip, the Mac laptop was in a Pelican box… too heavy and bulky, though I certainly had no trouble trusting its waterproofing effectiveness. When the console is done, the iBook will live in a sealed docking bay and move to my backpack when I’m off-boat; the Pelican box, if used, will carry instruments, spares, and documentation.

Navigation Tools: Good, but more needed. Besides the Marine VHF, the one always-on unit on this trip was the Garmin GPS-12XL. Wired to system power, it worked perfectly and has an efficient user interface. What is really needed, however, is a console-mounted chartplotter… my paper charts and manual nav tools (dividers, protractor, etc.) were a nuisance to use in the cockpit. In the long run, the handheld GPS and paper charts will be backups, and all routine navigation will be via the chartplotter (not PC-based nav software as originally planned; this is one area where single-point failure potential and power budget have to be taken seriously).

Lighting: Power hungry and a pain. The navlights are good (Aqua Signal), but are about to be retrofitted with stunning red, green, and white Luxeon LEDs driven by a board designed by Ned Konz. This will lower my 15-watt navlight budget to about 3-4 watts. In the cockpit, I’ll use diffused white LEDs; the current floating headlamp, flashlight, and candle system is ridiculously clumsy. Reducing dependence on stray gadgets is essential.

Power system: Good, but getting better. On this trip, I used a single Group 27 battery, proper bussing and distribution with Blue Sea Systems products, and charging from a 30-watt Solarex module as well as a Statpower AC charger. The latter appears confused and blinks an error light at full charge, and draws 30mA from the battery when not plugged in… it will be replaced by a dedicated line-operated switcher piped through Tim Nolan’s power management system. Tasha’s boat used a 3A Guest clip-on charger, but its setpoint is halfway between flooded and gel values (though it is much more waterproof than mine). The solar panels were not given proper charge controllers for this trip, just Schottky blocking diodes. All this will be upgraded as we turn our attention to systems integration.

This should provide a look into how it felt to spend time on water in the Microship. I can’t believe it’s been over a decade!

2017 note: there is a lot more information here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.