A Day in the Life of a Technomad

by Steven K. Roberts

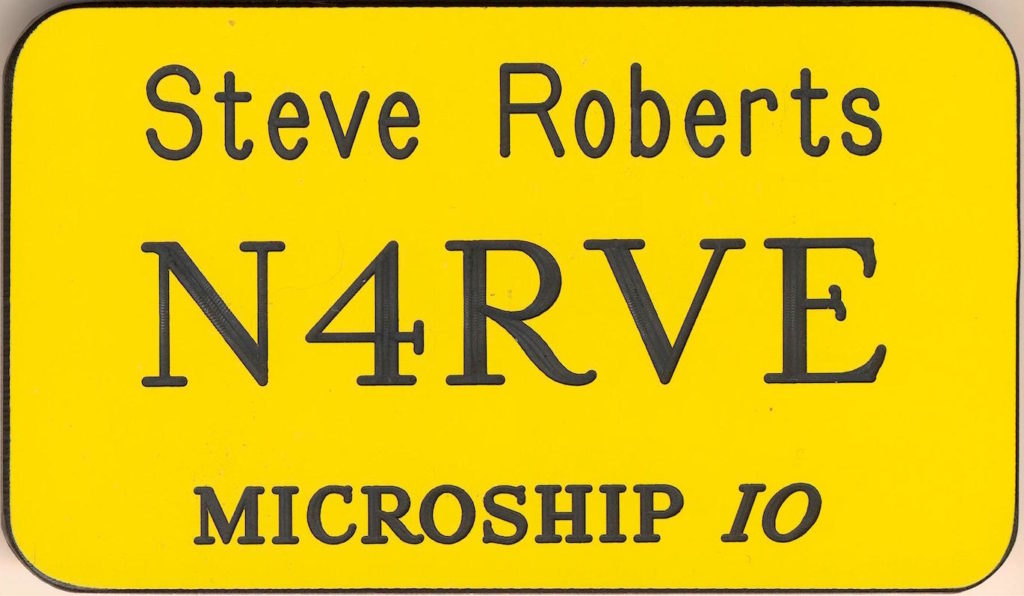

Microship Status Report #134

January 31, 2000

“Art without engineering is dreaming; engineering without art is calculating.”

— Steven K. Roberts

You know, it’s been a very long time since I wrote about the high-level specification that’s driving all this. With all the recent additions to the nomadness mailing list and our gradual refocusing on system design after years of work on the nautical substrate, I think it’s time to step back for a moment and look at the big picture. Besides, a refresher will do us good, and it might even help spot areas where long-cherished assumptions need to be questioned before we cast ancient legacy designs in concrete and irrevocably build upon them. As we move more and more into Linux, object Perl, and a wireless intranet of clients and servers frolicking behind a firewall with satellites on the other side, it becomes clear that some of our 1993 gizmology might have to be reconsidered…

A Brief Rhapsody on Art and Engineering

It is essential, when designing a complex system, to spend some relaxed time fantasizing about what it will be like when it’s done. After all, this is what drives the process of engineering: at some level between rigorous and fanciful, an image of the finished product must be held in the mind, savored, and examined from all sides. Only after this playful interlude (which, to a manager, may be disturbingly indistinguishable from unproductive wall-staring) can decomposition of the design into subsystems, tasks, and packaging make any sense.

Trying to shortcut this by starting on Day One with formal design methodologies can have the catastrophic effect of committing one to an ill-defined goal state, whereupon the end result is shaped more by design tools than the supposed objective. That’s why so many products seem malformed, patched, and otherwise inelegant… the industry loves formal tools, and generally looks askance upon such frivolous notions as approaching product design as a delicate blend of art and engineering. The exceptions, when they occur, are a joy to use. The rest simply miss the point, no matter how stylish their exterior… or how sophisticated the underlying technology. [more on this theme in my Gonzo Engineering piece]

With that in mind, let’s play with Microship system design at the highest level for a moment. What will this feel like, and what are we actually going to do with it? Perhaps a “day in the life” approach, though a bit cliché in a literary sense, will help integrate all these processors, networking layers, and distributed widgetry into some kind of a cohesive (and hopefully enchanting) whole.

A Day in the Life of a Technomad

My dreams are scattered by an Aaron Copeland trumpet fanfare that’s so absurdly grandiose in the context of a wilderness campsite in British Columbia that my partner and I simultaneously giggle awake and grin at each other. The music fades before the orchestra has a chance, then I hear a subtle click as the audio crossbar pipes the speech synthesizer to the Microship speakers.

“Good morning, campers… time to get up! Local time is 7:15, ambient light levels suggest sunlight, and the temperature is 58 degrees. Eight email messages have accumulated overnight, the main battery is at 91%, your portfolio is up .4% in morning trading, and all internal ship systems are within normal operational limits.” Somewhere in the heart of the Microship, an MP3 file starts streaming from disk, gets decompressed on the fly, and manifests itself as a delicious, spacey piece from Air entitled “All I Need.” I smile, seeing Pixel Toy graphics in my head, recalling nights in Amsterdam…

We wake and stretch, cozy in the tent nestled between Io and Europa… a pair of amphibian micro-trimarans parked parallel in the grass. Above us, a graceful custom tarp supported by retracted amas serves as rainfly and sunshade, and when we zip open the tent door it’s like looking out through a giant portico. As every morning, it takes a moment to believe where we are: gazing out at Gabriola Passage in the Gulf Islands, at last living the technomadic life that’s been the driving passion behind 8 exhausting years of development work.

While espresso hisses on the fold-down propane stove and Java the cat makes her morning rounds, we lazily do the preflight. I fire up a browser on the PowerBook and connect via wireless to the Microship on-board web server. The morning report was about right — no emergencies today (not like last week, when I woke to discover that console pressure was zero and the pneumatic controller had crashed… a potentially catastrophic situation in a saltwater environment). I quickly review strip charts of the power management system, scan the log of overnight telemetry transmissions to the hom-base server, and open Eudora to breeze through my email — fetching it from the IMAP server on the boat.

I open a new outgoing message: “Heading south today for Cowichan Bay. Just breaking camp in Drumberg Provincial Park. All systems normal. More after we launch… I’m still uncaffeinated.” This will go out during the next automatic hourly connection via Globalstar satellite, accompanied by an internally generated telemetry block that will add the latest snapshot of 50 or so time- and location-stamped sensor readings to the browsable database on our public website, along with a bucolic still image from the video turret on Natasha’s boat (currently pointed across the Passage).

Over latte and breakfast, my sweetie and I discuss the day’s run, which will be a bit critical in spots due to tidal currents. We’ve learned the lesson a few times in these waters… fighting the current is pointless and frustrating; working with it is like cycling with a tailwind. I don the wearable and bring up the chart and tidal data, emailing us both a few notes about waypoints and timing targets that can be popped up later on our on-board browsers.

But now — there’s no time to linger! We pack up the camping gear, kiss for good luck, and roll the boats down the beach on their deployable landing gear. I always like this part… smooth transition from land to water and back again was one of the key design goals, though for quite a while we had our doubts (going so far as to publish a story entitled “Why Boats Don’t Have Wheels“). We still have to struggle when we encounter goopy mud and rocky beaches, but this isn’t too bad… in a few moments the boats are bobbing in gentle lapping wavelets and we’re retracting the landing gear. A few more quick checks and we’re off.

There’s not much wind at the moment, so I keep the sail furled, deploy the SpinFin, and pedal into deeper water.

Here’s where it all kicks in, and there hasn’t been a launch yet that fails to deliver this feeling. I slip on the lightweight Xybernaut headset and bring up a zoomed-in nautical chart on the heads-up display; it’s oriented to my heading and shows my own location as a little boat icon, slowly tracking my movement. The console browser wakes up and displays the main monitor screen, with live power, network, diagnostics, comm, and sensor readings. All objects have a clickthrough that displays more detail — I crawl into the power management system and look at current measurements around the boat, check the power budget parameters, and see that we’re getting a healthy 16% gain from the set of eight peak-power trackers. I note with satisfaction that the cool weather and bright sunlight are already giving us an estimated power surplus of about 210 watts, enough to use the solar drive.

I turn around and deploy the Minn-Kota thruster, and set the console throttle to maximum free power: until I request otherwise, it will divert as much energy to propulsion as it can without impacting battery charging or internal system loads. I retract the pedal drive and kick back… watching the world silently slide by with only the subtlest humming and sussuration of water on the hull revealing that we’re cruising at 4 knots on sunlight alone.

Natasha’s voice purrs from the stereo speakers in the arch behind my head. “This is beautiful, Steve. Check out the video — I’m sending it over on the analog channel.” I click on a tool that opens the video crossbar chooser, and pipe the incoming material from Europa to the auxiliary console display. Nice shot indeed — she has the turret gazing back at herself, and I see a grinning woman peeking at me through a polycarbonate windshield that’s reflecting the low mountains behind Nanaimo… all surrounded by bright rippled sea foamed lightly by her wake. I send back a live grin from my console camera, and a few hundred feet away on her matching trimaran she snags snippets of both channels onto digital tape for later copying to the Casablanca — her onboard digital video editing system. With eight cameras between the two boats, including underwater units complete with hydrophones, there’s never a shortage of source material.

I pull a waterproof keyboard onto my lap (preferring it for speed and comfort over the chording unit embedded in the hydraulic steering levers), and work on the day’s email, then do a quick edit on a long-overdue article for Dr. Dobbs Journal. I seem to be more productive out here, for the noise level of deadline-driven life in the lab is but a memory and the writing process is intrinsically amusing. “I’m in a canoe,” I giggle to myself, tapping away as the islands drift quietly by. Suddenly thirsty, I pluck my insulated mug from its nest under the gunwale, hold it under the tap, and twist a knob: a little Shurflo pump whirrs to life and delivers a cold drink from a 7-liter tank. Ahhh, such decadence…

The morning passes lazily, punctuated by a bit of ham radio chat with folks on Vancouver Island and a discussion via Globalstar with one of our technology transfer partners about a spinoff project. We decide to stop in Chemainus for lunch, so we tie up at the public wharf, set security, grab the manpacks, and stroll into the pretty little town… enjoying the stretch. Sitting in a sidewalk cafe, I’m just starting to relax when my pack beeps insistently and the dual-band ham radio crisply utters, “Microship security alert: starboard microwave proximity sensor triggered at 1417 hours.”

I don the wearable headset and key it out of sleep mode… open Netscape, and click the HOME button to connect to the website aboard Io. It takes only a moment from the welcome screen to access a webcam tool that lets me switch among the available cameras. Natasha does the same via her laptop as I look around, scan the area with the steerable camera on the arch, and — aha! A couple of teenagers are enchanted with the solar panels and one is sitting on the dock, nudging them with his foot. Sheesh… no doubt harmless, but still… I click a button to power up the video recorder and start recording this channel, then turn on the laser adjacent to the camera, fine tune the Az-El controls to place an intimidating spot on the offender’s chest, open a channel from synthesizer to stereo, select a firm male voice via a pull-down menu, and crank up the volume. Finally, I type, “Remove your feet from my starboard solar array or I will begin reciting poetry!”

As the machine utters its ridiculous warning, he almost falls over himself in his haste to get away, looking around guiltily as other boatowners peer over to see what’s going on. The last we see of the pair, they’re sauntering off insouciantly with their hands in their pockets, followed by both my Az-El camera and Natasha’s video turret.

She wants to check out the town and I feel like being lazy, so we part company after lunch and stroll our separate ways. I’ve almost dozed off on the beach when I realize we’re pushing our luck with the currents, so I grab the handheld rig, key the mike, and intone, “Computer. Where’s Natasha?”. Back on Io, a task has been performing great circle calculations on GPS location beacons transmitted every minute via packet radio from both of our packs, and after my request is processed by the speech recognition system a soft female voice responds, “Natasha is .34 miles away on a bearing of 312 degrees.” I give her a call and remind her of the time, then return to the boat to get ready for the day’s final leg. On the nav screen, I can see her progress overlaid upon a detailed street map… pausing once as she’s drawn into an interesting shop and loses GPS coverage.

As we hoist our sails to catch the afternoon breeze and ride the current down Stuart Channel (congratulating ourselves on good timing — it’s not always this easy), I amuse myself with the telemetry system, watching tiny variations in water quality measurements and trying to correlate them with the surrounding environment. This is a lost cause in fast-moving waters, of course, but it helps the time pass… I get excited by a dip in dissolved oxygen and spike in turbidity as we pass a smoking mill and concoct a few theories, but it’s going to take more data than this. I flag it for later study and add a note to the file that will go out in the next hour.

As Seth Ceteras recently observed via email, I have become a sort of roving probe. “I imagine your boat floating serenely down a lazy river,” he wrote, “and in addition to the usual physical wake in the water, there is a data wake, a web-accessible data stream flowing back through all the time-spaces the boat had just, and indeed ever, inhabited.”

Ahhh, technology. We post our telemetry to our GIS-based Datawake server and are urging everyone else with live environmental feeds to do likewise… in time, with input from thousands of boats, bikes, trucks, planes, and people, this might yield a rich fabric with deep history that reflects the evolving health of the planet.

We end the day in Cowichan, cruising up the bay at sunset and arriving at the town dock to find Net friends waiting to spirit us off to dinner. We had given them a shout via terrestrial cellphone a few miles out, so the timing is perfect. After a brief demo, we stroll up the dock to town… but I pause and look back at Io and Europa — graceful little canoe-based trimarans resting silently on the water in the day’s dying light. Packed with computing power and linked via satellite to the Internet, they’re not at all what they seem…

News Updates from the Microship Lab

Inspired by the foregoing thoughts, much of our work these days has been focused on system development — with a parallel project getting underway to package a smart-battery powered clone of the Octagon-based Linux data collection system in a standalone waterproof box for the National Science Foundation. Tim Nolan is here from Wisconsin to spend another couple of weeks working on both that and Microship power management; custom circuit boards packed with PWM circuitry poured from his carry-on bags as he unpacked, and he’s in the software lab now, slaving away on battery-interface code.

Meanwhile, with the Perl Whirl and my solo Gulf Islands loop only four months away, I’m pushing hard to complete the essential nautical projects… that little fantasy tale is making my hull itch. The boat is now back on her workstand, and the landing gear are being disassembled, cleaned of the sometimes substantial corrosion from one brief test sail <shudder>, and bead-blasted in preparation for anodizing. The solar substrates are undergoing vacuum-bagging on Salt Spring Island, and I’m starting to design the pressurized console framework.

As you may have noticed in the story, we have a few updates in the moniker department. First, it’s really been bugging me that we haven’t come up with proper boat names — “Microship” describes the class nicely, but how to we label each object? For quite a while we were planning on Delta and Wye, which makes sense to electrical engineers; we dabbled playfully with Clewless and Lark, which makes sense to historians and punsters. But lately we’ve become rather enamored with Io and Europa… not only moons of Jupiter, but also names rich with mythological significance and considerable wordplay potential. Mine is Io (pronounced “eye-oh”) for it certainly has a lot of it; hers is Europa since she originated, after all, across the Pond.

Also, I kept referring in the preceding tale to some stranger named Natasha. No, this is not indicative of yet another shakeup in my traditionally volatile relationship milieu; Lisa is simply changing her name. Like me, she was adopted as an infant, and the Elizabeth handle never really stuck. We tried to rename her Lisa, but that didn’t quite fit either… so she’s now reverting to her lovely birth name, Natasha Clarke. Depending on conditions, we can apply interesting variations…. Nautasha when at sea, Naughtasha when she’s frisky, Nutasha when she’s silly, Netasha when she’s online, Pneutasha when she’s building up pressure, Gnawtasha when she’s eating… (OK, OK, I’ll stop now). She’s been busy on two fronts lately — continuing progress on Europa’s deck/arch structure, and complete top-down redesign of our entire website with loads of new features. She’s also looking into simpler landing gear and solar substrate alternatives than my living monuments to the Goddess of Complexity, and welcomes input from experienced welders and ‘glassers who would like to get involved in a fabrication project.

In the sponsor department, we’re grateful this month to Qualcomm for sending Eudora 4.2 to replace the comfortable old version I’ve been using for years. Yikes, what an upgrade… the search tools are spectacular, filters are improved, and it handles styled text and live links beautifully. And speaking of software updates, thanks to Capilano Computing for the latest version of Design Works… the schematic capture CAD package that we use for all Microship system documentation. We recently found out how to output the drawings as postscript to make them scalable, allowing inclusion of beautiful schematics in our PDF technical publications.

Qualcomm also sent the marine antenna for our Globalstar satellite link, and it’s now perched on the stern, just forward of the Handar ultrasonic wind sensor. It feels wonderful to be working on high-tech fixtures after all this time focusing on fiberglass and wheels (though we still have a disturbingly long nautical to-do list before launching on the northwest tour in late May… volunteers and Geek’s Vacation participants are very welcome!).

In Microship media news, we have a few updates to report: a brief piece in the “Rovings” column of Professional BoatBuilder (issue #62), a 7-page feature in the Russian Internet World magazine, a mention in the online “I, Cringely” column, a recent panel discussion about the technological future on Irish national radio, a pointer in the “Internet Waypoints” article in the next isssue of Northwest Yachting, and a forthcoming article in Wired Magazine (tentatively the May issue… including a beautiful photo of Io on her wheels in the forest).

Recent personal adventures include a resurgence in my improvisational flute playing after a lengthy hiatus, inspired by a brilliant group of local musicians and the remarkable experience of recording a jam with them last week. The stock market continues to be, well, um, amusing — causing annoying daily obsession with something I never thought I’d notice. I’m getting more involved in the fight against wanton logging of our island — it’s hard to believe there are still people who will mortgage the future of a beautiful place for a fast buck… but then, most of them don’t live here (our job, therefore, is to make the process as difficult and expensive as possible since appealing to their humanity is pointless). And along with everything else, I’m toying with the idea of putting together a technology-transfer organization to do something with Microship spinoffs… I’ll tell you more about that when and if it takes shape beyond the current exploratory discussion level.

You must be logged in to post a comment.