Departure from the Norm

Computing Across America, Chapter 9

by Steven K. Roberts

October 28, 1983

The whole object of travel is not to set foot on foreign land; it is at last to set foot on one’s own country as foreign land.

— Gilbert Keith Chesterton

I left Columbus, alone, on the eighth dreary day in a row. There were no TV cameras this time, no crowds, no friends to ride with me to the next state. I ate a quiet breakfast, put on my rain suit, and rode off into the murk.

The first feeling was simple relief, for the week in Columbus had been an exhausting one of modifying the bike and being a transient in what had recently been home. I watched the mileage increment on the digital display and relished every county line. (“Goodbye Delaware; hello Licking!” I cried as a green sign drifted past, chortling at the memory of a newspaper headline: Man Shot. Licking Woman Charged.)

I stopped atop a small bridge near Alexandria and ate an apple that seemed inordinately delicious. I laughed on, making jokes and sign-puns in the post-rain gloom, then stopped in the civilized little town of Granville to chat with professorial types and German grandmothers. I even enjoyed battling my way through Newark, where every traffic light turned red at my approach.

Yes, I was happy alright: this time I had left Columbus for good. This was no little jaunt in neighboring states, with friends and family standing by to take care of me. I was now facing unknown territory rippled with serious hills, and I had the distinct feeling that survival would be as much of an issue as comfort.

I was officially On The Road.

But the shakedown cruise had served an essential purpose. I was waterproofed and coldproofed from head to toe (making the miserable rain fun, in a twisted way). My camping equipment was refined all the way down to a new Dreizackwerk cooking knife. I had a stable kickstand that wouldn’t break every few hundred miles, a shiny stainless-steel steering linkage, improved packs, and a seat-side leather sheath for my dagger. The moisture-sensitive Push had been replaced by the manufacturer (although the new one already had its own problems), and I was armed with a sheaf of detailed county maps. My legs were even in shape — the shakedown had been my training ride.

And at last I was diving into the Whitman’s Sampler of lifestyles that had been one of my most alluring motives. Every day would be different, and I was growing addicted to change.

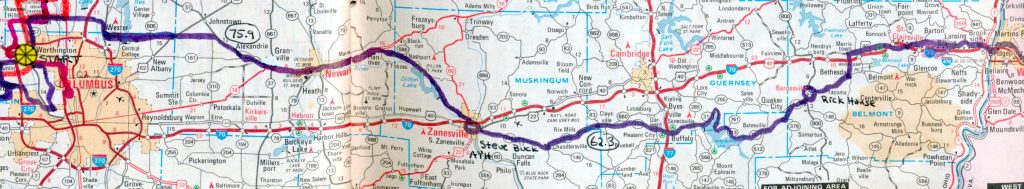

At the dark Halloween end of a 75.9-mile day, I arrived at the Zanesville, Ohio, AYH hostel — home of Steve Buck, judge candidate. Unlike the hostel in Caesar Creek with its rooms of functional bunks, this was a private residence, and I rolled in at a time of sick baby and family confusion. But the traveler’s bond prevailed: Steve took time away from speech-writing to swap stories and offer the welcome advice of a fellow cyclist. (“You’ll have to climb a three-mile hill right here,” he warned, pointing to Uniontown, Pennsylvania.)

After four years in Genericsville, USA, little hilly towns of clapboard houses and unselfconsciously quaint shops seemed relics of another time — a time of black & white TV and finned Buicks. I was less than a hundred miles from “home,” but unfamiliarity was already prying open my eyes and moving every detail from background to foreground.

On the way out of Zanesville, I stopped at a general store, a friendly little place of curled flypaper and slamming screen doors. While loading up on junk food, I told the lady that I had just been stood up by a local newspaper reporter.

“Well now, honey, it’s always like that around here. People in Zanesville — they’re a little slow to get around to things, that’s all. You know, a friend of mine went into the hospital for surgery just last week, and she was back home before they admitted her!”

It started with an adrenalin rush. I sweated and growled to the crest of a wooded hill in eastern Ohio’s Muskingum County, then looked ahead to see a long welcome downgrade. Ahh. Shifting to the smallest of the six rear cogs, I pushed hard with the intent of breaking my previous speed record of about 38 mph.

As gravity took me, I upshifted the front derailleur and threw the chain — abruptly locking the pedals. I had been cranking furiously and was just passing the 30 mph mark when this happened, and the sudden jam nearly yanked me out of my seat. I wavered across the road with my feet flailing against the ground, watching passing cars in terror while trying to bring the machine under control.

Somehow I stayed up and braked to a shaking stop on the side of the road. Loudly, crudely, I cursed not only this derailleur but all others as well, slandering the names SunTour, Campy, Huret, and Shimano like so many child molesters. I finally calmed enough to climb off and anoint my hands with their daily grease, wondering if this strange contraption would ever be fine-tuned.

But as the afternoon wore on, I sensed the exhilaration of travel. I thought of Walt and wished he could share this new frontier in cycling, so different from the flat roads we had come to know back in another life, another epoch.

He would be at Anatec now, tweaking his analog input circuitry for the CRISP process-control system. He’d be drinking black coffee from a glass mug, perhaps pausing occasionally to stare out the window at the eastern sky and wonder about his crazy traveling friend.

The roots were starting to rip.

On tiny route 313 near the boundary of Muskingum and Guernsey counties, I stopped to gaze over a long valley. Patches of sunshine drifted through the scene, highlighting distant herds of sheep and the occasional farmhouse. The fall colors were almost poetic, and only the rare passing car broke the pastoral silence.

But a dark, angry sky behind me dramatized the brightness to the north, and birds, big black ones, circled lazily overhead — one hovering above me with wingtips like splayed fingers fluttering precisely in the breeze. I watched in silence, and felt far from home at last. The roots were ripping further.

I stopped again, troubled and uneasy, to contemplate the Lake Seneca Resort. The black clouds I had seen earlier were closing fast, and I stood shivering at the locked entrance to a hillside community of mobile homes.

Something was wrong… there was no sign of life. The place was dark, motionless — the vegetation in the grip of autumn decay and the trailers as lifeless as the few abandoned automobiles forgotten in the weeds. I was spooked by off-season emptiness, imagining the lazy ghosts of summers past making daily commutes to the fishin’ lake. A kind of death hung in the air, and the roots tore free completely, leaving me dizzy and vulnerable.

I pressed on, chilled, the grades worsening. Was the bike geared low enough? I strained against gravity with a growl in my throat and a grimace on my lips, thinking only of the brief downward slope ahead — that sweet, violent reward that lies behind every hill. Within minutes, I would fly along at speeds touching 40 mph as the wind ripped tears from my eyes and spread them cold across my temples.

The visceral life! Could I ever go back to the mustiness of a cluttered house in Yuppiedom, to a life so tame that one hour of racquetball ranks as a major thrill? In one routine day on the road I had already sensed the rhythm of deepening hills, squinted through the gritty blast of air from passing trucks, jounced over potholes and railroad tracks that rattled the very bones of my machine, slid a greasy hand across sweat-slicked skin, relaxed to the chatterings of gears and birds, marveled at the image of my body as an engine, blinked away eyefuls of salty perspiration, smelled the farmlands of Ohio, and cried out in a moment or two of pure terror. Yeah, this was different, alright — even through the growing exhaustion of hill country there was a constant awareness of the joy of discovery and my own curiously variable scale relative to this planet. When I pondered the pedals, the earth seemed unimaginably vast; when I thought of the computer behind me and the networks filling the air, it seemed but a curious neighborhood.

This was not to be a normal bicycle trip.

On the road, on the road. I jogged over to US40 at Bethesda after a night in Barnesville, realizing that pretty little country roads also happen to be the steepest. Within two hours, I crossed the Ohio River into West Virginia.

Now, this was an experience not without intensity: there I was, face to face with the symbol of my fears. It seemed that everyone I talked to before leaving had either heard a West Virginia horror story or could relate one of their own — Jack the framebuilder had even whistled his machete through the air while telling a tale of his cycling encounter with hostile hillbillies.

The city of Wheeling was pretty, but I was on guard. The people at the Baskin-Robbins were friendly, but I stayed alert while eating my hot-fudge sundae. West Virginia. Oooh. I kept my face in a forbidding “Dirty Harry” squint, frisking passers-by with my eyes and refusing to notice their friendliness.

Back on the highway for the short trek to Pennsylvania, I studied every approaching car for signs of evil intent. Strangely, there seemed to be no shotguns, snaggle-toothed grins of deep malice, thrown bottles, or tattered pickup trucks running me off the road. Hmm.

Of course, this wasn’t the hard-core part of the state, but fear of the unknown is not always a product of rational thought. A Stroh’s beer truck making deliveries along US40 leapfrogged me time and again, and I finally relaxed enough to give the driver a hearty wave. And then I was in Pennsylvania. Just like that: two new states in the same day.

Boogie!

Pennsylvania. My, my. I pedaled along, marveling (“Man, I can’t believe I’m in Pennsylvania!“), enjoying a strong sense of getting away with something. In this early stage, the simple fact of being on the road and cranking out the miles still outweighed the more thoughtful considerations — a few minutes after this state line I was already eager for the next, and I watched the approach of my first thousand-mile mark with a kind of macho glee. The attitude is reflected in my journal, which contains only the most useless and superficial accounts of these first few weeks.

I was still too hungry for the meat to appreciate the spices. Or vice versa, depending on how you look at it.

Oh yes, hunger. It was that, on another level, that drove me to seek out Washington & Jefferson College when I arrived in Washington, PA. I had already sensed that colleges would be reliable sources of bed, food, and the kind of attention that could perk me up after a hard day’s ride, so I rolled up to the cafeteria and began what I soon came to call my dining hall routine.

It’s easy, really. I sat for a moment to cool off, then attached the kickstand/dog-whacker and dismounted.

With a long stretch, I took in my surroundings. Students enroute to dinner walked toward the door but stared at me, some stumbling to a stop as they intellectually grappled with the startling presence of the bike. I unstrapped the helmet and placed it over the yellow flasher, then removed my wallet, extracted a key, flipped open the electronics package, and armed the security system. I checked the Push to note the day’s mileage (in case curious fingers would happen upon the all-too-accessible RESET button during dinner), and tapped the day’s data into the computer.

I took my time at this, letting audience curiosity grow, then looked up with a sudden grin at a couple of the closer book-toting students. “Hey — how ya doin’?”

“Man, that is quite a bike. How far’d you come on it?”

I glanced at the display. “Coming up on the thousand-mile mark — 62.4 today. I’m just starting.” In what had already become a single smooth motion, I whipped out the atlas and presented the US map with my route highlighted in red.

“Wow! What are the solar panels for?”

And so on. Within minutes, the crowd grew to thirty or more, the questions coming rapid-fire. It didn’t take long; it never does in a crowd: someone different always emerges, someone who asks the good questions and seems to understand. He or she doesn’t have to be into computers or bicycle writing — all it takes is mutual recognition of that energy underlying every mad, sweet departure from dull acceptance of the ordinary.

In this crowd it happened with a senior named Mike, and we fell immediately into a spirited conversation that continued unabated through a food-service dinner. He offered me a place to sleep in the Kappa Sigma frat house.

Beer. Lugging packs to the third floor. Laundry and pizza. Foosball and studying. Questions, questions, and TV room camaraderie. A leisurely stroll of the campus, with longing gazes at the fresh beskirted bloom of feminine youth. More beer. More questions. The bike locked in a storage room. And through it all a swirl of fraternity life, a glimpse into another social world, and the first striking realization that my daily routine was becoming one of abrupt cultural readjustments.

Yes… every day was different, and every life I touched was magically opened to my curious eye. I could sample anything I wanted, for I was now living the stranger-on-a-train syndrome. Everyone I met wanted to talk to me, and the possibilities were endless. I was riding the ultimate door-opener, an eight-foot-long key to the exploration of realities that I could hardly begin to imagine. There were still all those basic original motives of adventure, lust, fun, escape, public adulation, and living a fantasy, but it was now dramatically clear that I would actually learn something.

And the best part was that I had no idea what.

You must be logged in to post a comment.