The 3-Mile Hill

Computing Across America, Chapter 10

by Steven K. Roberts

October 31, 1983

First Nastassja Kinski’s dog, now this?

— Loretta in Uniontown, PA

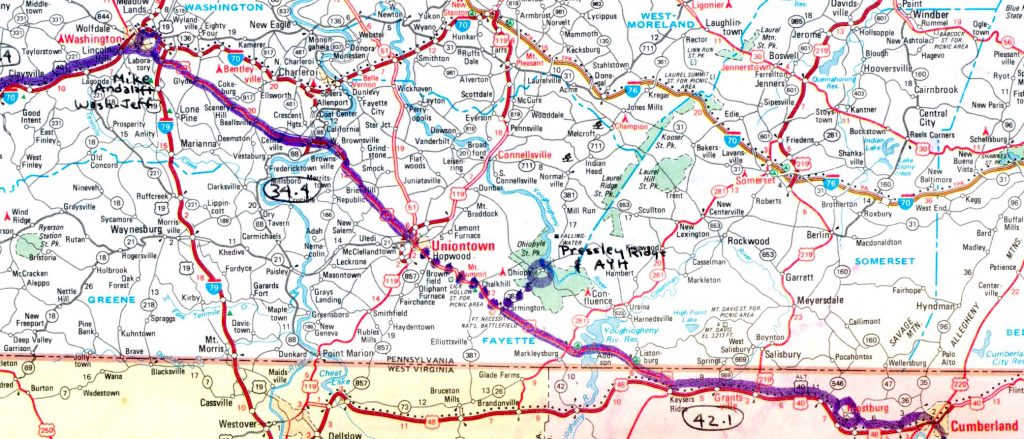

I arrived in Uniontown shaking with exhaustion after a mere thirty-four-mile ride from Washington & Jefferson college. The distance was short, but it had been a tense day of gusty crosswinds on the narrow and busy US40. Directly ahead was a wall — a three-mile hill that I had been hearing about for days. I considered briefly and decided to worry about it in the morning.

At about 4:00 in the afternoon I stopped at the Uniontown Mall to cruise the shops before seeking a motel for the night. I rolled the bike through the doors, clipped the security beeper to my sweatpants, and went for a stroll. A little window-shopping here, a scan of a magazine rack there — it was the usual mall experience with an unfamiliar constraint. I could buy nothing that wasn’t bikeable.

I returned to my high-tech steed and found three women standing around it.

Loretta, a spry and diminutive 78-year-old, was holding forth on matters of local history. Annie, an attractive woman in her fifties, was studying the bike and making notes on a scrap of paper. Mary, her striking five-foot-ten, red-haired daughter, was looking directly at me and smiling. The ladies were energetic, fascinated, and filled with compelling stories, and when we got around to the practical matters of interviews and places to stay, Mary set off to make a few calls.

Suddenly a mall rent-a-cop appeared on the scene and interrupted the rest of us. “Hey! What do you think you’re doing with that bike in here? Get it outside!”

I nodded meekly and moved to obey, but Loretta — gray, tiny, and feisty as hell — placed a strong restraining hand on my arm and turned to the cop. “What!” she hissed. “Don’t you have any idea who this is? First Nastassja Kinski’s dog, now this?

“Well, ma’am, it’s the rules.”

“Rules! Who’s your boss, young man?”

“Uh, the mall manager.”

“Where’s his office?”

Well, ma’am, it’s down that way…” The cop, taken aback by the old woman’s intensity, was behaving like a child caught pulling his pants down behind the barn.

“I’ll just have a word with him! You wait right here.” Loretta turned briskly on her heel and strode off into the Muzak-filled confusion of the Uniontown Mall. The cop shrugged and stood glumly aside to await judgement.

I was quite willing to forget the whole thing and roll the machine outside, but then Mary reappeared with deep green eyes and a smile. She stood closer than before, and I felt a tightening in my chest and a sense of lightheadedness. This was unexpected: in fascination, I held our gaze past the point that marks the onset of intimacy. Her beauty was not the kind that dazzles at first glance, but the kind that slowly grows deeper, unfolding from moment to moment like a desert sunset.

“The Herald-Standard is coming over,” she said softly.

I gave her a blank look. “What?”

She smiled again. “You have a newspaper interview. And I’ve found you a place to stay.”

“Ah, thank you!” My imagination was soaring.

“My brother is a director at the Pressley Ridge Wilderness School — if you don’t mind doing a little presentation for the kids, you can stay there.”

“Oh, that sounds interesting. Where is it?”

“In Ohiopyle.”

“Hmm. I doubt if I can make it by dark — that’s over the three-mile hill, isn’t it?”

“Yes, but I’m arranging a van ride now. We’ll get you there!” Through all this, her eyes remained locked with mine, making my heart pound as if I had just crested the hill of which we spoke. Mary was getting prettier by the minute, and I had to struggle to keep from immersing my hand in her flowing red hair.

Loretta came striding back with a look of triumph. “Young man,” she said to the cop, “your boss wants to talk to you.” She turned to me and said in a theatrical whisper: “I can’t believe these people. Do you know that last year they told Nastassja Kinski to get out of here — just because she had her dog with her? A cute little dog! One would think they could show people a little more respect.” She shook her head, indignant, and stared daggers at the retreating uniform. “Makes me ashamed sometimes, it does.”

I was pleased to discover that I have something in common with Nastassja. I filed that away for my first date with her, and thanked Loretta for standing up for me. But now I had to take the bike outside anyway, for there was a newspaper reporter eagerly looking it over and mumbling something about losing the light. We did the interview — yielding a story called “14,000-mile Trip on Bizarre Contraption” — and I turned again to Mary.

Smiles. Twinkles. We fanned the spark into a warmth that chased the evening chill as darkness blanketed Uniontown. Her features were full and well balanced; her voice melodious, almost tuneful. Every smile felt like a total-body massage with warm almond oil, and I was ready to follow her anywhere. Especially home.

But one of the Pressley Ridge counselors arrived in the school van, and we soon found ourselves packing my awkward machine in the back. With a tingling hug I bid Mary farewell (“Call me,” she whispered), and we were off — climbing the notorious three-mile hill under gasoline power. Gasoline… I felt like I was cheating. I still wince at those fifteen miles of atlas marked not by a bold red line but by wimpy little dots.

We turned onto a narrow road and coasted downhill for miles while the engine made muffled backfiring noises. Autumn was well advanced here in southwestern Pennsylvania, and the van’s passage set up a rustling wake of elm and maple leaves on this little-used road. Daniel, red-faced and red-haired, talked with a proselytizing intensity about the school and the philosophies behind it.

“Pressley Ridge isn’t the usual kind of school — did Mary tell you? Right now we have about one hundred eighty emotionally disturbed boys between the ages of eight and eighteen. They live in the woods, not in dorms; they build their own shelters and plan most of their own activities.”

“Sounds wonderful,” I said. “The last school for problem kids I saw looked like a prison.”

“Yeah, this is a radically different approach. Our environment leads to the development of a strong culture — we’re constantly amazed at how much the boys help each other, how much they care. There are problems now and then, but we seldom think in terms of punishment. Peer pressure is a powerful tool, you know, and a lot of other difficulties are solved by the law of natural consequences.”

“The what?”

Daniel glanced over at me, his bearded face eerily lit by the glow of the dashboard. “If the boys don’t cut enough firewood, they get cold. If someone won’t do his share of the work, the others put pressure on him. They meet every day to discuss activities, identify problems, help newcomers, and so on. Our job has less to do with discipline than guidance — we’re role models, friends, mentors — “

“But don’t you ever have runaways?” I asked. I was having a hard time imagining nearly two hundred youthful troublemakers living together in peace and harmony.

“Not very often. Some kids never do respond to this environment, of course — we get quite a few who have already done time in traditional schools. They’ve been labeled as failures, truants, or discipline problems, and they tend to resent everybody. But most of them come around… we’re showing an eighty-three percent success rate for smooth reintegration into society.”

Fascinating. I had always pictured schools for “problem” boys as institutional training grounds for young criminals, not idyllic communities in the woods.

“There’s a lot to be said,” Daniel continued, “for the boys’ own resources. That’s what we try to encourage: their natural desire to learn. They have to develop math skills to plan meals and build shelters; they need language skills to produce the school paper. They have a library, and they really use it. When the boys come up with an idea for a field trip, they’re the ones who take care of planning and logistics. The whole program is based on curiosity and the desire to grow. There’s no stronger motivator.” He slowed the van and pulled up in front of a small, quiet building.

“Where are they now?”

“In the dining hall — Chief Larry is doing a slide show of his vacation. You can come in on the tail end of that and tell them all about what you’re doing. If you carry a gun or drugs, I’d appreciate your not mentioning it.”

We unloaded the bike and I rolled into the darkened dining hall. The boys were there: relaxed black and white faces illuminated softly by light from the screen. One adult stood in the middle of the crowd, operating the projector and talking above its fan.

Unable to resist the opportunity for a grand entrance, I switched on all the bike lights. Brilliant one-per-second xenon strobes penetrated the darkest corners, and the wall behind me blazed yellow in the light from my barricade flasher. A small group across the room squinted in the headlight, and a rising chorus of “WOW!!!” drowned the voice of the speaker. I wailed the freon horn in greeting.

The slide show was quickly brought to a close, and I had the floor. For an hour I told tales, demonstrated the machine, and bantered with this energetic and responsive crowd; by the time it was over I was as intrigued by them as were they by me. I think it was their focused attention — and their questions, which tended toward the keen and practical. I have spoken since to groups of “normal” kids, and the response is usually on the predictable level of “Ooooh man, check it out! Can I toot the horn? How fast does it go?”

But life at Pressley Ridge is different. These boys have survival and development of their community as top daily priorities. Instead of six hours vegetating in a classroom followed by long evenings of staring passively at TV madness, they spend their time building cabins, exploring, cutting wood, working out their problems, and learning self-reliance. After the original oh-wow, their questions were right on target:

“How do you do your laundry?”

“When you’re on the road, where do you go to the bathroom?”

“Could you explain the computer again?”

“Hey, how you get yo’ money? An’ yo’ mail?”

“Do you carry spare tires?”

They understood. The solar panels weren’t gee-whiz space-age gadgets from a junior science magazine — they were a practical way to produce electricity on the road. The computer wasn’t for playing Space Invaders — it was for making a living. (“All I have to do,” I explained, holding high the Model 100 with a grin, “is push a bunch of these buttons in the right order. Then people send me money.”)

A sort of mutual fascination developed between us, growing stronger the next day as I wrote an article by their huge fireplace, strolled in the woods, and toured their elaborate homebuilt living facilities.

“We periodically have the boys tear down their cabins and start over,” Daniel told me as we walked a long path to the Quehanna tribe area.

“You what? Isn’t that frustrating?”

“Not at all. There is an ongoing turnover here, and we want everyone to have a personal investment in the place. It wouldn’t do for newcomers to live in houses built by people who were here before them, would it?”

I found myself filled with envy, wishing that my education had been so well-rounded. In an emotional farewell talk to a small group, I tried to convey this feeling.

I let one of the kids put a message on my recorder:

“Hello. Breaker breaker 1-9. Chief Larry. Kirk Russell. Robby Brenaman. Todd, Chuck, Ivan, TA, Rich, and Bill. And Michael Smith. Zigga, zigga, zigga 1-3. C’mon now…”

“I know you guys were sent here for a reason,” I said. “You had trouble at home, got busted, or kept screwing up in school somehow.” A couple of them nodded. “And I don’t know — maybe you see this place as some kind of punishment. But lemme tell ya something: You guys got it made, man. I wish I’d gone to a school like this. You know what I did when I was your age? I spent all day trying to stay awake in school, then went home and messed around alone in the basement, building electronics stuff. I went to summer camp once, but we were treated like little kids. I didn’t learn how to build cabins and help my friends through problems; I braided plastic lanyards and got an ear infection from swimming in a polluted lake. You guys are like a family, no matter what it’s like back home. I wish everybody could spend a year in a place like this.”

We shook hands all around, and the circle of small faces looking up at me wished me good luck and asked me to “send a card from out there, man.” They called me Chief, and said a solemn good-bye. One of the counselors later commented that some of the boys would probably build a model recumbent bicycle out of saplings.

You must be logged in to post a comment.