First Microship Launch

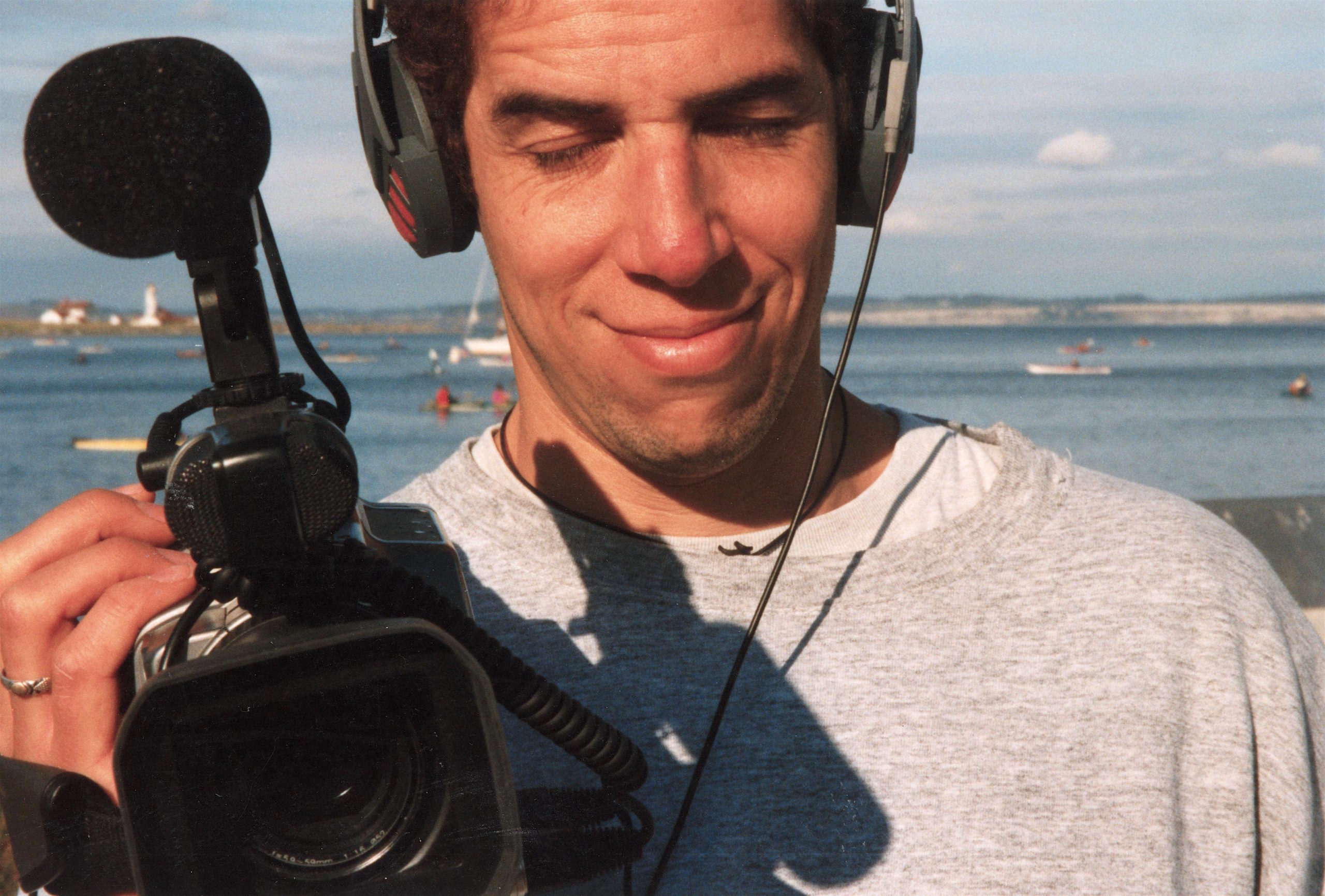

This was an insanely intense time… with a film crew from Canada, we did the last-minute push to get the Microship ready for its first-ever launch, at the Sea Kayak Symposium in Port Townsend. Like trade-show deadlines, this had a galvanizing effect, compounded by being on camera. The piece opens with a wonderful video 3.5-minute demo done by Picture This Productions… using footage gathered during their visit with us during this crazy week, produced with the idea of selling a weekly feature called TECHNOMADS.

Microship Status #126

Steven K. Roberts

Camano Island, Washington

October 2, 1998

“While engine development has fallen behind schedule, we are confident that we will have the unit delivered before the aircraft’s first flight.”

inexact recall of a real memo (passed along by Bob Stuart)

First Microship Launch!

Ah, now this is more like it. After an interminable epoch of being the Nomadic Research Labs facilities manager, it is nothing short of exhilarating to return to the Microship project… especially with the recent thrill of the first-ever test launch of the boat. We’ve been fantasizing about this for well over a year.

The mad push began about a month ago — you may recall my offhand mention in Issue #125 that I’d be speaking at the West Coast Sea Kayak Symposium and planned to sail there. As in any industry where trade-show dates drive the development process, this became such a focused deadline for nautical functionality that an acronym was born to label all things that could wait: APT (After Port Townsend).

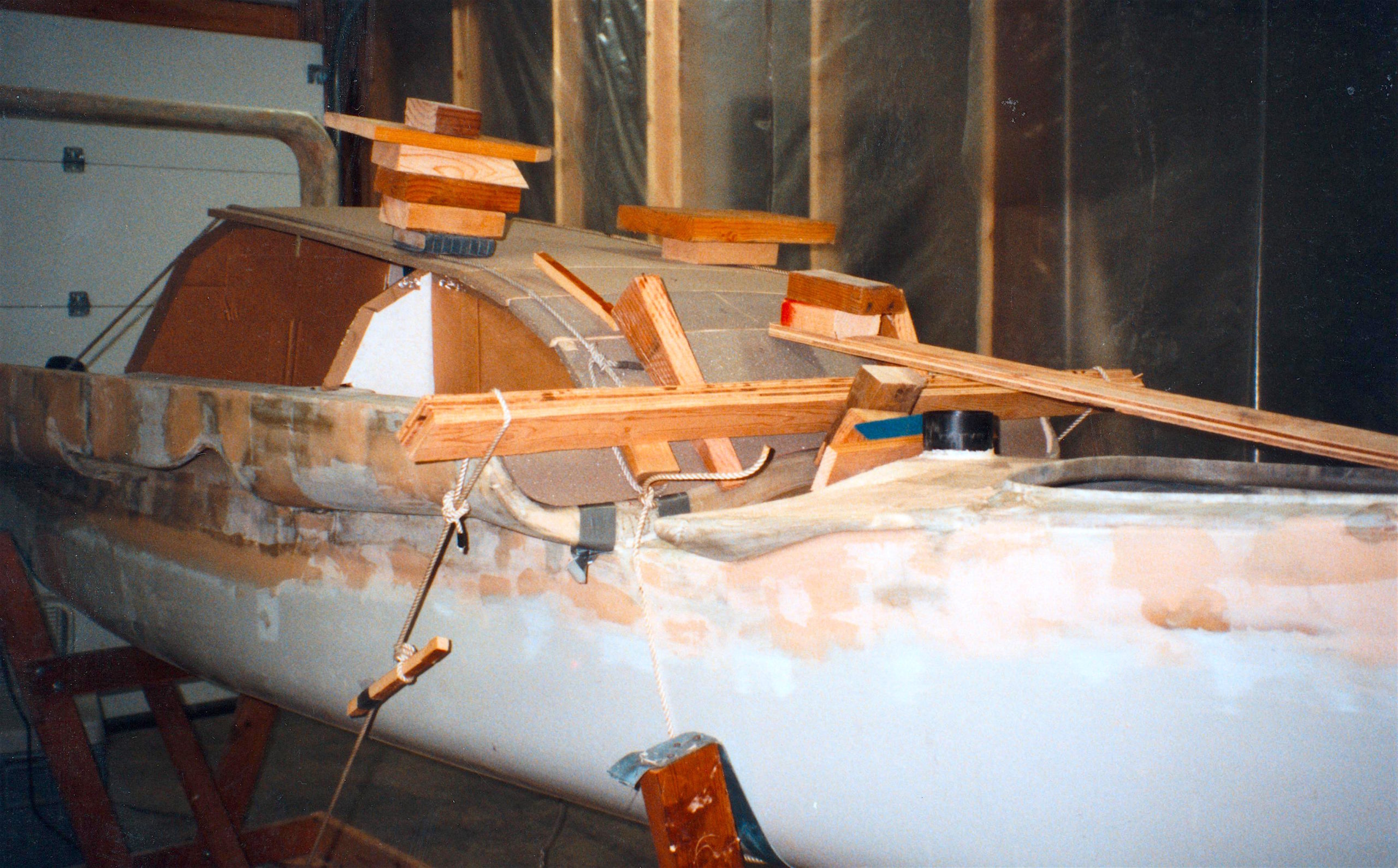

Parts were ordered; machining jobs specified; and lists written (then trimmed to reflect reality). What projects were absolutely essential to take the Microship on water for the first time, and of those, which would yield permanent fixtures and which would be test-only? With the daggerboard trunk cast in glass, for example, the only knobs left to twiddle for helm balance were board length and rudder placement; we elected to kluge a non-retractable test rudder controlled by awkward bridle-tugging rather than spend a month refining the hydraulics and kickup system for a real one that might end up in the wrong place. On the other hand, the adjustable seat, pedal drive system, rigging, furler, and console cowling would involve a huge amount of work whether we did them right or not… so we elected to go ahead and do them right. At this point, we kicked into high gear and maintained hacker’s hours for the next three weeks (with a few all-nighters thrown in for massive fiberglass layups and time-critical projects).

Tim Nolan, visiting on our Geek’s Vacation program from Wisconsin (more about him below), spent his first afternoon fashioning a temporary rudder fixture steered by a copper Tee plugged into the tiller hole, cheap cabinet hinges, and scrap plywood hot-glued to rudder and hull. I spec’d a load of Ronstan rigging components — Series 38 ball-bearing blocks, cleats, mainsheet traveler, and other nautical hardware — and got it all on order with only days to spare. Steve Goshorn, a machinist here on Camano Island, set to work fashioning a load of aluminum parts designed by Bob Stuart to allow a wide range of recumbent seat movement — with vernier adjustment of fore-aft, up-down, and angular positions. And it seemed that every other day we zoomed off to Everett or Anacortes to prowl marine-supply and hardware stores for stainless bolts, pricey line, hatch straps and buckles, shackles, and essential bits forgotten on the previous day’s trip.

Down in Silicon Valley, Andrew Letton started fabricating the pedals — a decidedly nontrivial project constrained by difficult stress problems, ability to withstand lateral grounding loads on the 5/8″ drive shaft of Bob’s “Spin Fin” drive unit, removability for on-water bivouac, and minimal operating envelope. After a few marathons and all-nighters of his own, the package was shipped — joining the Ronstan goodies and other accumulated hardware on the bench with only a week until scheduled launch.

Meanwhile, Bob was practicing his art — fiberglass and mechanical fabrication. He sculpted a beautiful cowling that defines the console shape, and drove us crazy with endless refinement of the foam-core deck in preparation for painting (seemingly premature, but for the fact that ultraviolet rays damage unprotected epoxy resin). The results of all the filling and sanding marathons were worth it: once painted, the boat bespeaks smooth grace and balance with nary a glitch in her seductive curves. I fabricated a Divinycell-and-doorskin furling drum, then Lisa glassed it to the aluminum mast after first removing a ring of black anodizing and doing an acid etch to allow epoxy adhesion… whereupon Bob and I turned it down with the angle grinder to make it pretty. Little bosses and lands of filled epoxy were integrated into cowling, akas, and deck as needed to support various turning blocks, fairleads, and clamcleats — and the boat, for so many months a piebald patchwork of glass and goo, suddenly began sprouting shiny metal parts with a decidedly nautical flavor.

Final staging. A documentary film crew (Maureen, David, and Craig of Picture This Productions) arrived from Quebec, hoping to catch frenzied last-minute lab action and the uncertain excitement of first launch, and we decided to truck the boat to Port Townsend and do the test there — she just wasn’t ready for a 50-mile sail. Bob assembled the drive unit and integrated it with the pedals using Andrew’s machined-Delrin pillow blocks and Trantorque couplers; I fiddled for hours with the critical drilling and mounting of precisely parallel seat supports on a deck with no flat surfaces, then moved on to rigging and the temporary Spin Fin deployment lashup. It’s all a sleepless blur in retrospect, but somehow we found ourselves slapping on a fast-drying Interlux primer/filler coat… even pressing David the cameraman into service on the morning of departure to help finish the painting before first public rollout amidst a thousand kayakers.

In a mental fog, I piloted the mothership over 75 indirect miles to reach the Keystone ferry, where I paid $42 to take ‘er aboard for the short hop over to Port Townsend and the Sea Kayak Symposium.

Saturday dawned way too early, and before my normal latte-time I was on stage chatting about electronics packaging methods on tiny boats. We extracted the Microship from the truck and rigged her on the workstand, perched incongruously atop tiny casters on the conference center’s lawn. The furled 21-foot rig raked the sky; the prop spun smoothly with every touch of the pedals; the overall effect looked like the mutant offspring of a Klingon battle cruiser and a snowy egret. Crowds gathered and questions flew, the fascination with a pedal drive system evident in this paddling culture.

And then it was time.

Creaking and complaining, the workstand — never intended to be used outside the smooth concrete floor of the lab — began its journey. With four of us manhandling the akas and countless others forming a sort of protective phalanx, we rumbled through the soccer field and onto the roads of Fort Worden, creating a bit of a traffic jam and pausing at one point to heel the boat 30 degrees to sneak under power lines. At a busy intersection with a curious queue behind us, a cop strode over purposefully and opened his mouth to order me off the road, but in a flash David was there with the video camera in his face, asking what he thought of the Microship. He shrugged and waved us on.

The photo above shows us walking the Microship down the road on its fragile workstand with police escort (photo by Maureen Marovitch) – click below to play one minute of video from that crazy event:

First launch of the Microship – 1998 in Port Townsend from Steven K Roberts.

After a long downhill reach to the beach, we dragged the tiny 2″ wheels sideways to turn into the ramp area, paused a bit to strategize, then backed her straight into the water. The workstand by now was a bit wobbly and trapezoidal, with cracks radiating from drywall screws, but it held together until the boat floated lightly off and unseen hands wrestled it from the sea and stashed it on the beach.

And there she was… afloat for the first time, resting on the water as gracefully as a leaf even with an empty weight of 337 pounds! The design waterline painted on the canoe hull was parallel to the water; the amas barely kissed. So far, so good.

I clambered into the webbed recumbent seat (after ducking under an aka and soaking the crew’s wireless microphone with salt water <cringe>), tightened the temporary steering bridle, deployed the thruster and locked it down with a ball-detent pin into a temporary fixture on the hull, and slowly backpedaled… she effortlessly glided along the dock and turned to face open water. With a wave to my friends and the cameras, I kicked her into gear and she flew! Mike Cichanowski, president of Wenonah, paddled vigorously alongside in a kayak as I pedaled — giving me a useful data point on speed (I neglected to bring a GPS). Maintaining 3-4 knots was comfortable, amazing when you consider that the thrust is provided by a 13-inch, 2-blade model airplane propeller… we’ll gather hard performance data next time.

Once away from the docks and stray boats, I retracted the drive unit and drifted a moment until she was still. Time for the next test…

I uncleated the furling lines, which run 2.5 times around the drum and through a couple of exit blocks in the leading edge of the cowling, and wrestled with them a bit to find the sweet spot between slipping and binding. In moments, I had the sail unfurled, and rushed to tighten the outhaul running along the boom. All so unfamiliar, yet intimate: not only have I been specifying, building, buying, and staring at this stuff since the beginning, but there was also a tangible sense that it will all become very routine someday… even though the new inputs flooding my senses were so complex that I could barely keep up. The WindRider sail snapped into a lovely shape, instantly easing my fears about the vertical battens, and I hurried to drop the daggerboard into the bizarre forward-angled trunk and lock it down with <blush> a couple of tapered wooden shims left over from hanging my office door.

And in a rush we were off! Before I knew it, I was flying the windward hull, the canoe and leeward ama slicing through the water silently but with unmistakable speed. She tacked easily… and I was instantly relieved to see that there was just the slightest hint of weather helm: when I released the rudder, she would head up gently into the wind.

Tech note: This is a Very Good Thing, for the opposite can get you into trouble in heavy airs by falling off into a high-stress condition that can cause capsize or dismasting if you don’t quickly uncleat the main. Heading up when rudder control is lost essentially depowers the boat and leaves you in irons. Accomplishing this requires that the below-water CLR (Center of Lateral Resistance) is slightly forward of the above-water CE (Center of Effort). As each is the complex resultant of many factors that can themselves vary with wind conditions and reefing, I have never felt too confident in our highly-critical daggerboard placement… which is one of the reasons we used a temporary rudder lashup for this test. We left ourselves one last adjustment before having to tweak the balance with Sawzall, grinder, and fiberglass… but it looks good.

I was vaguely aware of Lisa chasing me around in a kayak with waterproof Pentax in hand, as well as David with his video camera perched in the front seat of a double paddled by Matthew Smith of Current Designs. I was lost in another reality entirely. The fantasies and design meetings, the PERT charts and ambitious specification documents, the late nights and countless dollars, the whole lab-construction project… all snapped into focus and pointed as one to this moment. The boat actually works! Giddy with the sensations, I tacked back and forth in the waters off Point Wilson, realizing that the project had just made a quantum leap into its next phase.

Reluctantly, I refurled the sail and pedaled back to the dock — already growing comfortable with the turning radius and general feel. Bob took ‘er for a spin under pedal drive only, pushing hard to test the system… then we adjusted the seat to give Lisa a go. It was all so surreal… I stood on the shore and watched this lovely little vessel scooting amidst the kayaks as sunset pinked the sky, while my mind, like Kai software, magically rendered the details of a matching boatlet, bristling antennas, sparkling blue solar arrays, white radomes, and LCDs alive with graphic reflections of my systems, my sensors, my life…

Microship Fabrication, Phase 2

And so, we’re back in the lab with many an unknown resolved… and many a task ahead. Bob has been working all week on the real rudder, a robust and smooth contraption based on the Moore Sailboats carbon-fiber blade, a bulbous yet sleek head assembly with embedded gudgeons pivoting around a stainless pintle set into the canoe stern, a fiendishly clever retraction system that allows uphaul/downhaul/kickup/stow control with a single line and pivoting bolt, and yoke control via double-acting hydraulic cylinders coupled to sliding handgrips riding on traveler tracks. The port grip doubles as a throttle control, and the starboard contains the chord keyboard… yes, we’re actually thinking about electronics now.

We’re also running through the whole list of deck fixtures — all the widgets that require lands, bosses, hard points, or other special accommodation in the foam-core fiberglass deckage. I’m pondering the pressurized console, antennas, lights, vents, horn, deck compass, video turret (The turret! Remember the turret?), and the suite of lines, levers, and hydraulics that allow control over the Microship… even landing gear deployment. Suddenly it seems everything is on the front burner, for the boat itself actually works <swoon>.

I’m firing up the FORTH network this week, hot on the trail of a linux front-end server and links to the packet-radio-based APRS network. I just returned from the TAPR Digital Communications Conference in Chicago, where I was treated to three days of high-bandwidth input from a group that embodies the original spirit of amateur radio — passionate experimentation and the relentless pushing of technical limits. More ideas, more integration of once-complicated hardware lashups into single devices running clever code… yes, all is as it should be. Keith Sproul donated a copy of MacAPRS to get me started… much more on all this in an upcoming issue, I’m sure.

Thruster Management System

Speaking of clever design, we had a particularly successful “Geek’s Vacation” participant recently — Tim Nolan from Madison, Wisconsin. He works in automatic theater-lighting controls and was ready for a break; he arrived and dove right in, first getting acquainted with the boat by building the temporary rudder lashup noted earlier.

But his real focus was the solar/thruster management system, a key design problem that has popped up in discussion quite a bit but never really been addressed. Basically, we need a dedicated processor that does a power management survey every few seconds and then allows the thruster just enough power at maximum throttle to cruise as fast as possible without impacting the battery… unless an impending emergency forces manual override.

Tim’s first task was to make one of the New Micros 68HC11 FORTH boards control the Minn-Kota 42EX thruster by hacking the front end of the latter’s PWM (Pulse Width Modulation) controller. This turned out to be easier than we expected, requiring only closure of a forward/reverse direction switch and presentation of a 0-4 volt level to the “top” of the original throttle control pot. With this, and simple 4-bit D-A converter hanging off an output port, he was able to keyboard-command any of 16 power levels from all-stop to 42 relentless pounds of thrust (which makes quite a mess in a 16-gallon open test tank!).

The other half of the problem is data collection. To make an informed decision about how much “free” power is available at any given moment, the controller has to look at the battery manager (which runs autonomously and is responsible only to the battery), the instantaneous total of all connected loads including the thruster itself, and the power that each half of the solar array is capable of producing. This is the subtle part, and involves doing peak-power tracking calculations based on current and voltage measurements with switched dummy loads. The solar interface is not yet complete — Tim will return in November to wrap it up using a test array of Solarex modules, an E-Meter from his electric truck, and a Trace C40 battery charger — but he already has the node power-cycling and reading five Microswitch Hall-effect current sensors via the internal 8-bit, 8-channel A-D converter on Port E.

Not bad for a week’s work… and he was a relaxed and pleasant house guest as well!

News ‘n Notes

We owe thanks to another volunteer — Rich Muttkowski, whom we met while shopping at Eagle Hardware in Mt. Vernon. He’s an amazingly productive fellow who wanders by once a week to take on miscellaneous jobs around the lab; already he has hung a monstrously heavy Dutch door in my office, installed and wired an electric wall heater, and retrofitted the boatshop workstand with huge wheels to simplify outdoor maneuvering. Next up is connection of the underground waterline to an outside hydrant, and possibly even hang gutters before the rains get too much worse. Endless building details remain, but good help such as this eases the pain.

Also, I’ve been meaning to thank Mark Moorcroft, who generously donated his Wilton vise just as we were leaving Santa Clara. It has proven to be an indispensable shop tool, and lives right next to Big Red, the drill press. Other than a bench sander/grinder and a suite of handheld power tools, that’s about it on the machine-shop side… we’re still watching for a decent brake/shear as well as a bandsaw. (For now, our “bandsaw” is the Sawzall chucked upside-down in the vise!)

One wonderful new machine, however, is Miss Piggy — a huge barrel-shaped woodstove that we lucked into for only $50. It’s not installed yet, but believe me, it’s becoming a very high priority… looks like the real dollars are going to be in triple-wall stainless stovepipe.

And oh yes, I guess I better get this on record: the press release about our large-scale manufacturing facilities in Issue #125 was a JOKE, folks! I’ve had a number of serious responses…

We’ve had a bit of media recently — the Everett Herald ran a front page story in the local section on September 24 with two color photos of us working in the lab. This led to quite a few bits of email from local techies, many of whom are now on this mailing list. There’s also a story coming in Home Office Computing, another in the new magazine Telecommute, and a few burbles of fresh video activity on the horizon.

Eric Gullichsen, an endlessly interesting chap, has been hanging out in Tonga and starting up a new TLD registry… he visited us last month and kindly donated technomad.to (the .com version was snagged in 1995 by a speaker company). Dunno what I’ll do with it, if anything, but it’s fun to have domain names that correspond to my neologisms (I now hold microship.com, nomadness.com, technomadic.com, and technomad.to). For a near-infinite resource of domain names in a tiny kingdom that, in a curious reversal of history, is now colonizing Cyberspace, check out Tonic…

Now, back to it! The next Microship launch is Sunday, October 4, at the State Park on Camano Island… time to test the new rudder system and do some performance comparisons with the Fulmar-19.

You must be logged in to post a comment.