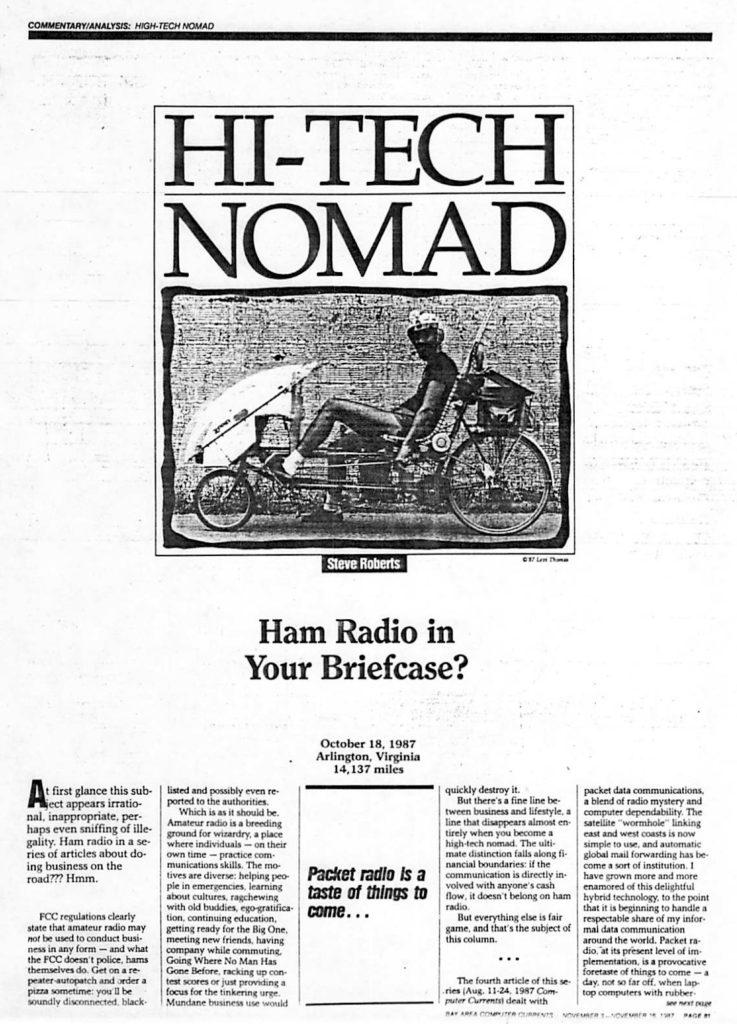

Ham Radio in Your Briefcase

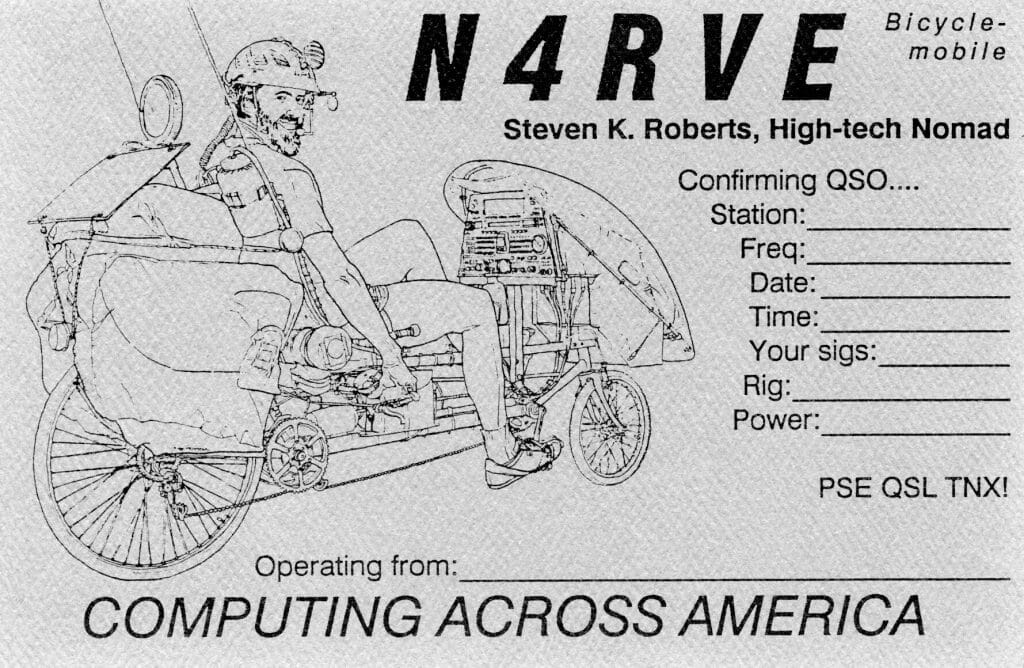

by Steven K. Roberts

Computer Currents

October 18, 1987

Arlington, VA — 14,137 miles

At first glance this subject appears irrational, inappropriate, perhaps even sniffing of illegality. Ham radio in a series of articles about doing business on the road??? Hmm.

FCC regulations clearly state that amateur radio may not be used to conduct business in any form — and what the FCC doesn’t police, hams themselves do. Get on a repeater-autopatch and order a pizza sometime: you’ll be soundly disconnected, blacklisted, and possibly even reported to the authorities.

Which is as it should be. Amateur radio is a breeding ground for wizardry, a place where individuals — on their own time — practice communications skills. The motives are diverse: helping people in emergencies, learning about cultures, ragchewing with old buddies, ego-gratification, continuing education, getting ready for the Big One, meeting new friends, having company while commuting, Going Where No Man Has Gone Before, racking up contest scores, or just providing a focus for the tinkering urge. Mundane business use would quickly destroy it.

But there’s a fine line between business and lifestyle, a line that disappears almost entirely when you become a high-tech nomad. The ultimate distinction falls along financial boundaries: if the communication is directly involved with anyone’s cash flow, it doesn’t belong on ham radio.

But everything else is fair game, and that’s the subject of this column.

The fourth article of this series (Aug. 11-24, 1987 Computer Currents) dealt with packet data communications, a blend of radio mystery and computer dependability. The satellite “wormhole” linking east and west coasts is now simple to use, and automatic global mail forwarding has be come a sort of institution. I have grown more and more enamored of this delightful hybrid technology, to the point that it is beginning to handle a respectable share of my informal data communication around the world. Packet radio, at its present level of implementation, is a provocative foretaste of things to come — a day, not so far off, when laptop computers with rubber-duckie antennas will be a common sight… an efficient way to handle business and personal electronic mail without wires.

But there’s a lot more to hamming that makes it an ideal tool for the business traveler. The most apparent is two meter FM.

I don’t know about you, but when I wander through unfamiliar lands I like to be in touch with people. It’s comforting to know that I can holler for emergency services if necessary… or just nose around the band a bit and find someone to keep me company for a few miles. From the Yaesu 290 on the bike, I have made phone calls, arranged a place to sleep long before arriving in town, called the police to report an accident, assisted stranded motorists with phone calls, learned about all sorts of tekwizardry, and been entertained. I chat with Maggie on low-power simplex while riding along, forgetting sometimes that we’re on two bicycles a half-mile apart. And always there’s the sense that, if something goes wrong — from a brutal attack to a broken connector — I can push a button and quickly find assistance.

The psychological value of this cannot be overstated.

So who’s out there, anyway? The demographics of the ham community are skewed by the screening effects of the licensing procedure — prospective amateur radio operators must pass a Morse code test (five words/minute for the lowest license class) and a written exam. This keeps the service from degenerating into CB drivel, but it also keeps out many kinds of intelligence and leads to a disproportionate number of techies. This can work to your advantage, however, if you’re wandering the country with a load of gizmology… for the local repeater may be one of the best resources around for experienced tinkerers, tools, parts, and hot tips on where to find support services.

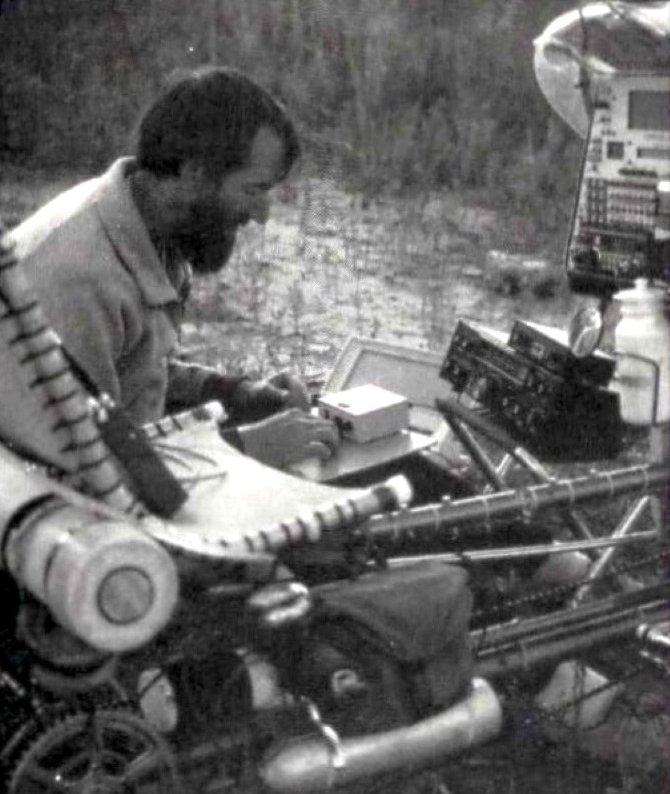

In addition to two meter FM and packet, ham radio offers a variety of intriguing modes that can help you do everything from keep in touch with folks back home to change your view of the world. I now carry a full-spectrum HF (high-frequency) station, running from solar-charged Ni-Cad batteries, that can — under the right conditions — transmit around the globe. This morning, pushing two watts into a dipole antenna tossed into my host’s oak trees, I contacted a fellow in Germany and tried unsuccesfully to get through to the Soviet Union. Last night, in one final fling before bed, I worked Michigan and South Dakota in a narrow crack between two high-power international broadcasters. Two watts — about the power of a typical miniature Christmas tree bulb — into 66 feet of wire…

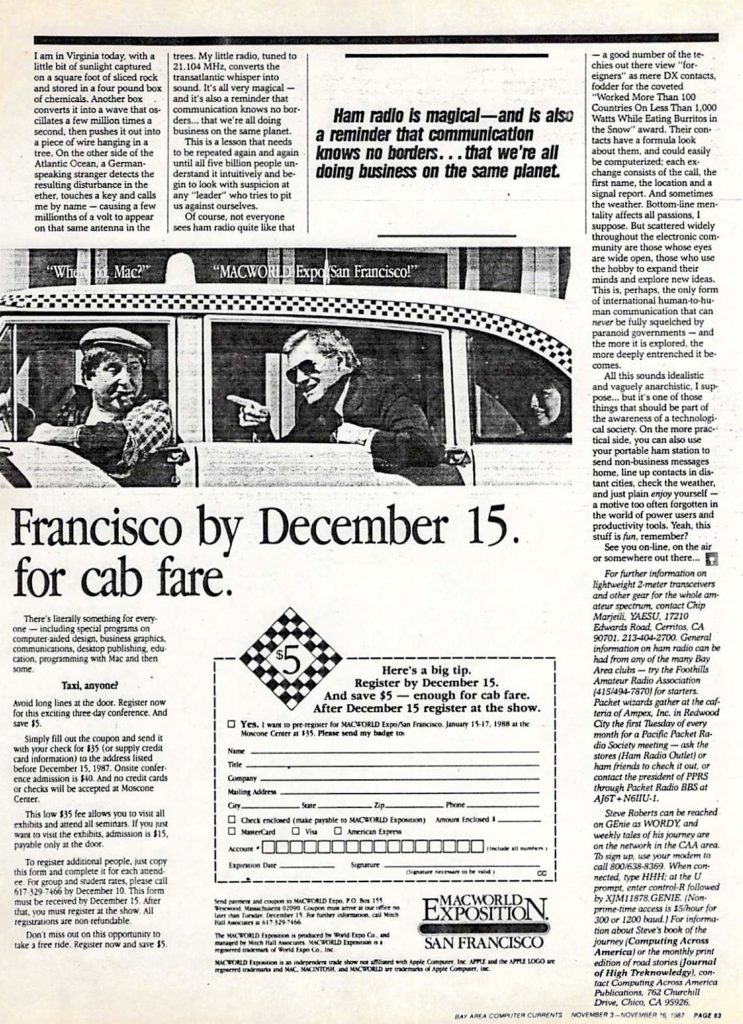

The feeling I get from all this is one of wonder, something that seems to be slipping away from our electronic society. We take electronic mail for granted now, hardly conscious of the complex infrastructure that renders simple our daily communication. A megabyte in a laptop computer no longer seems particularly unreasonable, and an overseas phone call is occasion only for the smallest of thrills. Of course it works, as do facsimile machines, laser printers, and Mac IIs. But here I am in Virginia today, with a little bit of sunlight captured on a square foot of sliced rock and stored in a four pound box of chemicals. Another box converts it into a wave that oscillates a few million times a second, then pushes it out into a piece of wire hanging in a tree. On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, a German-speaking stranger detects the resulting disturbance in the ether, touches a key and calls me by name — causing a few millionths of a volt to appear on that same antenna in the trees. My little radio, tuned to 21.104 MHz, converts the transatlantic whisper into sound. It’s all very magical — and it’s also a reminder that communication knows no borders… that we’re all doing business on the same planet.

This is a lesson that needs to be repeated again and again until all five billion people understand it intuitively and begin to look with suspicion at any “leader” who tries to pit us against ourselves.

Of course, not everyone sees ham radio quite like that — a good number of the techies out there view “foreigners” as mere DX contacts, fodder for the coveted “Worked More Than 100 Countries On Less Than 1,000 Watts While Eating Burritos in the Snow” award. Their contacts have a formula look about them, and could easily be computerized; each exchange consists of the call, the first name, the location and a signal report. And sometimes the weather. Bottom-line mentality affects all passions, I suppose. But scattered widely throughout the electronic community are those whose eyes are wide open, those who use the hobby to expand their minds and explore new ideas. This is, perhaps, the only form of international human-to-human communication that can never be fully squelched by paranoid governments — and the more it is explored, the more deeply entrenched it becomes.

All this sounds idealistic and vaguely anarchistic, I suppose… but it’s one of those things that should be part of the awareness of a technological society. On the more practical side, you can also use your portable ham station to send non-business messages home, line up contacts in distant cities, check the weather, and just plain enjoy yourself — a motive too often forgotten in the world of power users and productivity tools. Yeah, this stuff is fun. remember?

See you on-line, on the air or somewhere out there…

For further information on lightweight 2-meter transceivers and other gear for the whole amateur spectrum, contact Chip Marjeili, YAESU, 17210 Edwards Road, Cerritos, CA 90701. General information on ham radio can be had from any of the many Bay Area clubs — try the Foothills Amateur Radio Association for starters. Packet wizards gather at the cafeteria of Ampex, Inc. in Redwood City the first Tuesday of every month for a Pacific Packet Radio Society meeting — ask the stores (Ham Radio Outlet) or ham friends to check it out, or contact the president of PPRS through Packet Radio BBS at AJ6T+N6IIU-1.

Steve Roberts can be reached on GEnie as WORDY: and weekly tales of his journey are on the network in the CAA area. To sign up, use your modem to call 800-638-8369. When connected, type HHH; at the U prompt, enter control-R followed by XJM11878,GENIE. (Non-prime-time access is $5/hour for 300 or 1200 baud.) For information about Steve’s book of the journey (Computing Across America) or the monthly print edition of road stories (Journal of High Treknowledgy), contact Computing Across America Publications [obsolete address redacted].

You must be logged in to post a comment.