Instants of Recognition

Computing Across America, chapter 37

by Steven K. Roberts

Santa Fe, New Mexico

August 10, 1984

You came saying “show me who you are”; the tourists came saying “show us what you got.”

Steve Northup, Time Magazine

The shape of the northern horizon kept changing, the storms and mountains sparring with lightning punches as I pedaled past. This is a wild, violent land; I rode gawking like a midwestern touron even as an unfamiliar exhaustion began to grip me.

I was over a mile above sea level and climbing, growing weaker by the hour, struggling with an effort out of proportion to the tame grades of I-25. By the time I reached Pecos I was staggering, panting, and assuming the worst. Must be the goddamn flu.

Just beating the daily rain, I checked into the Wilderness Inn, one of those gracious surprises that appears when least expected and most needed. I wiped off the tires and weakly wheeled the Winnebiko into the adobe/vigas building, through a hall of polished antiques and hardwood floors, squeezing it at last into a small but tasteful room. And I came to realize after showering and relaxing that I was fine — the problem was not with microbes but hemoglobin. The air was thinning: I was in the mountains at last, and my blood had not yet adapted. (Even at this altitude, water boils at a tepid 182°.)

That was reassuring, but I was growing depressed about something else entirely. Do you have any idea how intimidating it can be to leap into a competitive genre with a book contract when you are carrying a few hundred journal pages of meat-and-potatoes notes? The task seemed impossible, especially in the creamy light of the sky show that was just beginning.

Sighing, I gazed out the window. The day’s rain had ended in a huge double rainbow, arcing from the muted bulk of the Sangre de Christo into a northeastern sky already alive with the reflected colors of sunset. I stared at it with a feeling of inadequacy, realizing that my job was to “plunder with my eyes,” as Theroux wrote. Not only did I have to see this, but I had to wrap words around it — words that could conjure images ranging from the shimmering rainbow itself to the shock I felt when it suddenly winked out and a mercury-vapor streetlight flickered on in its place.

“Hey, wait!” I wanted to shout. “I haven’t seen enough!” But time passes, and with it, sensation. I scribbled hastily in my journal during rainbows and conversations, insights and inspirations, leaving little reflections that could but dimly capture the intensity of the original. It’s a frustrating business.

And as I penetrated the massive folds of the mountains, this became a challenge at least as big as the skyward pedaling itself.

Through the kind of random happenstance that yields the best memories, I met John Wyckoff.

It was an accident, actually. Next to the Pecos Restaurant was a little gun-surplus-survivalist place; ambling away the overload of a Mexican dinner I stopped in to chat. The two guys there were combat junkies, war-lovers, boot-knife-carrying weapon fanatics in camouflage jackets. One had yearned to go to Vietnam, but was too young at the time. Somehow we ended up in a discussion of handgun stopping power, with both of them naturally urging me to carry a piece on the bike.

“But however you look at it,” one said, “you get down to the old Catch-22. If you mess somebody around to keep him from messing you around, you’ll have to answer to the law. You can take your pick.”

I observed that avoiding the issue made more sense.

“It’s not that easy — it’s a crazy world out there. I can’t believe you haven’t been attacked yet. You know, what you really oughta do is attend our two-week special action commando school.” He handed me a crudely produced flyer promising new skills in guerrilla warfare, ambushing, sniping, infiltration, knife fighting and more. Not bad for four hundred dollars. The flyer noted that “you have not lived until you have almost died, and to those who fight for it life has a flavor the protected will never know,” adding that “Communist or Marxist-prone individuals need not apply.”

I said I’d consider it, and promised them a look at my human-powered assault vehicle on my way to Santa Fe.

The next morning, following their directions, I turned onto a long rutted road west of Pecos. I stepped carefully toward the ragged house, wary of tripwires and punji stakes, holding my empty hands in clear view while listening for the metallic click of a carbine.

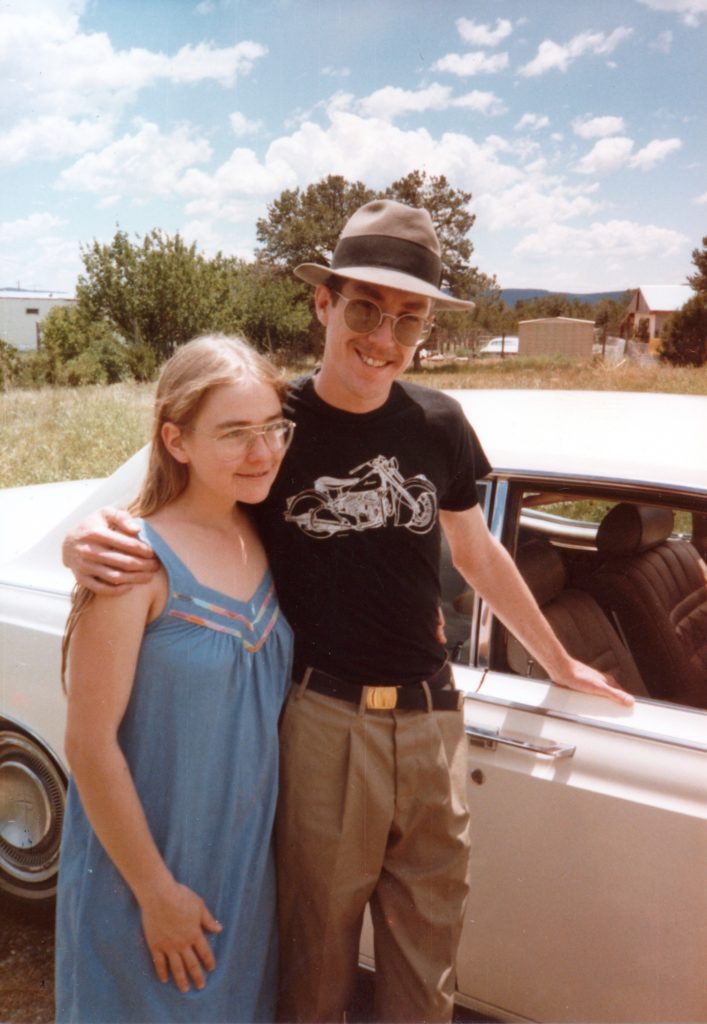

A clean white ’69 Lincoln Continental was parked next to a run-down outhouse. I stepped onto the front porch of a shuttered home standing poised and silent, took a deep breath, and knocked.

Nothing. Again, louder.

Footsteps and grumbling from inside. The latch. A hungover, unshaven skinny guy opened the door, rubbing his eyes and squinting in the daylight. Oops. Wrong house.

“Uh, I’m looking for—” I began.

“Hey, didn’t I just read about you in Popular Science?” he asked, looking past me at the bike parked in his yard.

“Er, yes, that was me. I’m trying to find—”

“Well, come on in! I didn’t think there was more than one recumbent bicycle with solar panels around! You want some coffee?”

I grinned. “Sure, why not?”

And thus began a most entertaining three-day visit with John Wyckoff and friends.

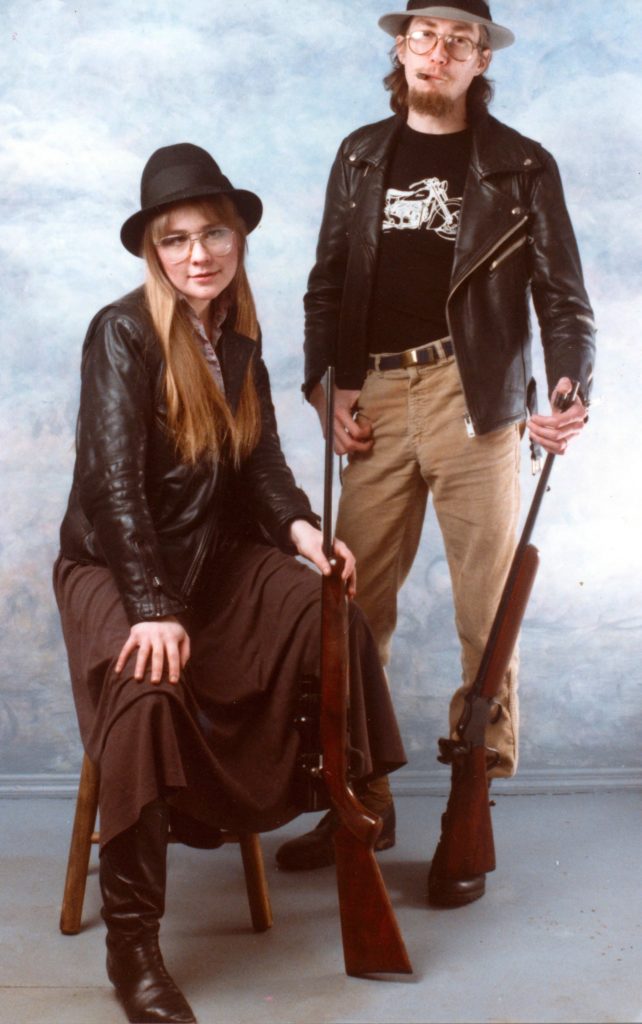

John is a quintessential generalist, a man whose experience ranges from the handcrafting of fine musical instruments to the historical development of model airplane engines; from gunsmithing to trout fishing; from the psychoacoustics of speaker design to film processing; from science-fiction esoterica to gutter humor. He plays Renaissance music with slender fingers dancing on a Moeck recorder — and manufactures devastating handgun ammunition called “Onslaught.”

I was kept busy making notes as John, always the showman, poured forth his diverse wisdom in accents various:

On politics: “We live in the era of the democratic liberal pinhead, where if you’re a victim they figure you must have done something to get yourself into that position.”

On drugs: “They told us that LSD causes chromosome damage, and now we have proof: hippies grew up and had punks.”

On Greer Garson, whose lavish ranch is nearby: “She’s not quite as cruel as Betty Davis, and not quite as aloof as Tallulah Bankhead.”

On depression: “If I had the greatest idea of my life right now, I’d probably discard it.”

His ego is potent, but it is backed up by substance; his hat, never far from his head, is a cherished Stetson Waltham Luxuro-finish Sovereign.

He is married to Beth, the quiet, amblyopic daughter of a prominent cancer researcher. She’s intelligent, artistic, pretty, and meek — overpowered in this remarkably successful relationship but radiantly happy. She’s supportive, almost worshipful, and when he hugs her, she beams. Her hat is of black felt.

Their semi-permanent houseguest was Rob, longhaired, chubby, soft, quiet, seeming slow until issuing random and unexpected gems of insight. He was to John as Ed McMahan is to Johnny, and his hat was military-surplus camouflage.

Mine was a Bell Tourlite bicycle helmet.

The four of us went trout fishing in the Pecos Canyon that afternoon, whispering down winding roads in Connie, the cherry Continental. Perched on a wooden bridge, we dropped our lures and popped our Shaefers, the fishing slow, the conversation lazy. John squatted on the bridge, tending two poles, smoking a cigarette, looking in his Stetson and blue Oxford shirt like a cross between a thin gangster and a west-coast engineer.

I leaned back, not really caring about the fish, and savored the scene. My eye was startled at every turn by land vertical, topsy-turvy. Trees made acute angles with hillsides streaked here and there by the scars of ancient rockslides, and all around was a sense of power and timelessness.

A crusty old billygoat methodically stripped the leaves from a small bush nearby, eating with caprine puckishness. Trees on the canyon walls moved enough in the wind to give the scene an acid-like sense of fluidity, a log house perched among them fitting its surroundings like a wish-book fantasy of newlyweds. The languor of the trout fishing, the haze of the beer, the caress of the sun — all conspired to make this a day of discovery and relaxation.

Publishers seemed far away.

The Pecos stay was an endless treat of image and insight, a swirl of sensation and unusual experiences so exotic that I felt more like a traveler than ever before. I actually tried to leave the next morning, lusting after the new computer only thirty miles away, but the hailstorm started the moment I got the bike packed. I ducked onto the front porch to watch: marble-size stones hopped vigorously around the fields like millions of white grasshoppers hell-bent on eastward migration. Their sound on the tin roof was loud enough to be unnerving, almost industrial in its insistence. What I could see of the sky was blue and bright, yet the air was filled with falling objects.

I rode into Santa Fe from the east as the sun shot diverging shafts of steamy pastel into the neck-cricking lands around me. One mountain ahead was dark but for its peak, a fuzzy mound of split-pea fuzz floating in the haze of afternoon clouds. Surroundings like these tend to dwarf a city and keep it in its place.

Lands of grandeur command respect.

Santa Fe begins gently from the Old Pecos Trail approach, its adobe colors rising from the ground with little garishness to irritate the sensitive eye. The city fits the body of the earth like a layer of fine clothing — instead of ravaging it like a development rapist. And the resulting character touches the people.

For three weeks I bounced about this trendy new-age town, waiting for the Hewlett-Packard computer to arrive and working my way through the layer of protection that has been constructed around the community itself. This is big-time tourist country, and the more interesting segments of local culture have long since learned to stay out of the spotlight.

I soon found out why. As a new visitor to Santa Fe, I was drawn immediately to the plaza — one of those break-dancing, cruising, street- vending areas where tourists mill by day and “youth” lurk at night. When the sun shines, it’s like Key West’s Duval Street, but instead of a T-shirt- based economy it is one of turquoise, silver, and objets d’art.

And, naturally, tourists are exploited in that age-old symbiosis of hawker and gawker — a love/hate relationship between a town overrun and a picture-taking plague of credit-card-carrying intruders.

I quickly learned to avoid the plaza, which is too expensive anyway. In tourist country, everything is a show whether it wants to be or not, and I was surrounded, deluged with questions, and forced to pose time and again — once dragged out of a camping-supply store mid-transaction by a rude Illinois woman whose husband was already sitting on the bike, bending the kickstand and sporting my helmet backwards atop a vacant grin.

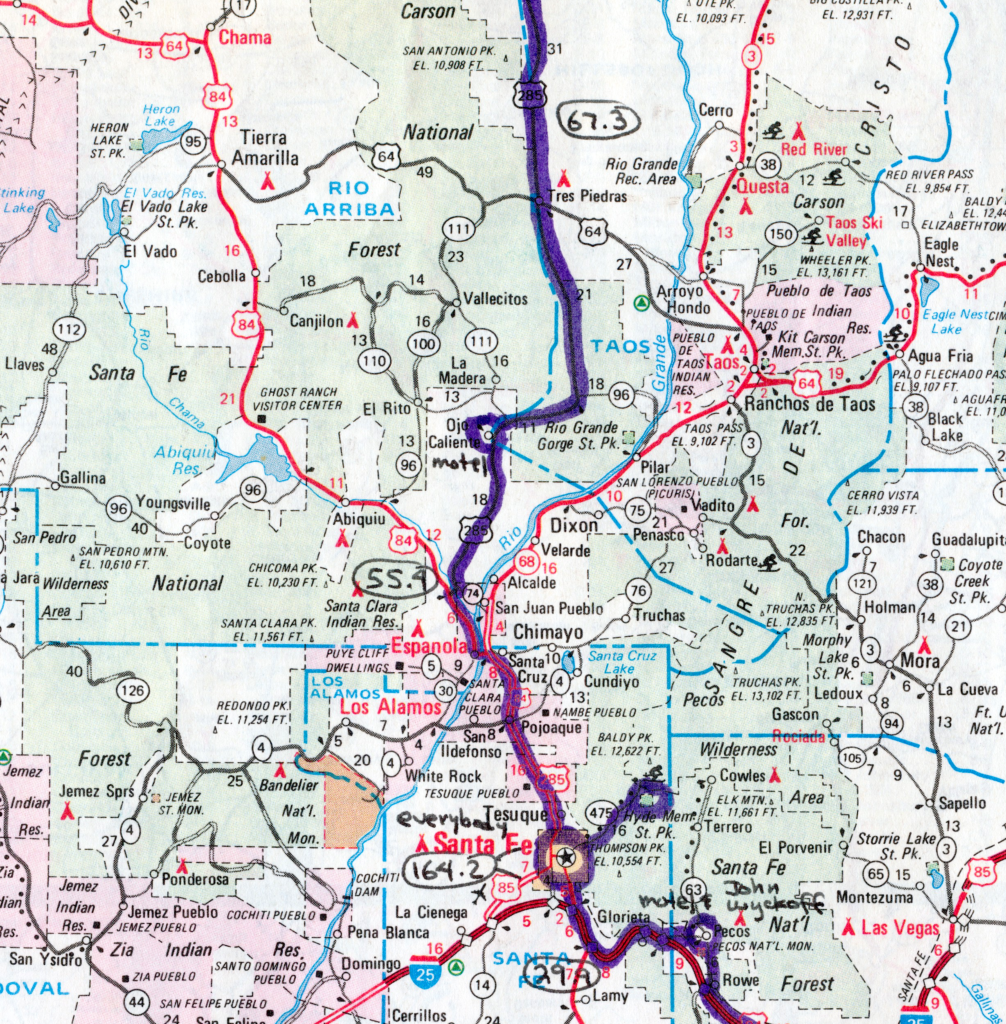

I chased him off and pulled out the map to show her the 6,400-mile red line of my journey. She peered at it through bifocals for a moment, and then cried, “Oh, that’s marvelous! So tell me, where are you now?”

I patiently pointed to the map. “Ma’am, I am right here with you, and we’re in Santa Fe, New Mexico.” She nodded in affected concentration as if listening to a tour guide. By now, we were the focus of clattering Kodak Discs and sunburned faces, mouths flapping in mutual interruption as questions filled the air. Who pays you to do this? Have you been robbed? How do you steer? I felt like merchandise on sale in a busy department store, picked over and prodded, going fast My own purchase in Base Camp was still sitting by the cash register, mid-transaction.

One self-important graying bozo with safety glasses spoke loudly above the rest, his voice dripping with disdain. “You know what some yo-yo told me after he seen your bike over there by the restaurant? He said the solar panels are for the lights. Now where you gonna get sun at night!” He bellowed a hearty laugh at his own cleverness and glanced around at the audience.

“He was right,” I said. “There’s a battery.”

“Yeah, but…” he began, then saw the pointlessness of arguing. With a scowl he grabbed his wife and moved along to the turquoise-hustling area.

A burned-out character with short hair and stubbled chin homed in on me, asking for spare change and making the tourists back off. But then he wouldn’t leave me alone, droning on like a bad fluorescent about Guatemala and gringos and police and what a hit I’d be in Latin America and why he’s on probation and what’s wrong with El Salvador — continuing even after I turned pointedly and walked back into the store. His voice followed me, ending at last with a curse and the words “…stupid bike anyway.”

I hoped I hadn’t yet found Santa Fe.

I kept probing, sensing a magical community in hiding, and then at last I started to see it — a deeply rooted new-age counterculture population, coexisting with an even deeper foundation of Mexican-American ethnic roots. There are barrios and communes, low riders and high flyers, practitioners of religions old and cults new. This is a city struggling to both exploit and retain its unique character, a task with as many casualties as victors.

A glum New Yorker at a Bed and Breakfast had just been fired from his construction job for refusing to talk to trees before cutting them down. When it was suggested that he spend some time in quiet communion with them, he fired up his chain saw and shouted at the nearest piñon pine: “Hey, Mr. Tree! I’m gonna cut your ass down!” The chips flew and he was fired on the spot.

One of my Santa Fe hosts went to a pot-luck dinner with an environmental group headed by the owner of a natural tobacco company. Health-conscious tobacco….

At a party one night, I was thrust into a time warp. This was new-age hippie culture, an echo of the 1960’s amplified by the determined specialization of the 1980’s. Talk was of acupuncture (two schools in town), shiatzu, macrobiotics, aikido, I Ching, and astrology. Tae Kwan Do is very Yang in nature, I learned.

Santa Fe is full of spiritual alternatives. I had a close-up look at a new twist in Christianity that would doubtless leave the Bible-belt folks bewildered (though not as bewildered as they would be by Southern California’s mohawked punk Christians).

It was the home of Natasha, a short and bright weaver whom I met in an entirely different context. She lived with three other people as a close, loving family: Peter, her fella, calm and into new-age martial arts; David, gentle and bright, writing a coffee-table book on spirituality in the movies; Joan, serious and religious, color-coordinated in pinks and purples. The house was a spacious vigas/adobe structure in the hills above town, the religion a strange blend of Christianity and new-age consciousness.

Everyone hugged. The teakettle played a pleasing chord. I was warmly welcomed, and dinner was excellent.

Here and there were notes taped to mirrors and walls:

I am putting SE’s (spiritual exercises) first in my life and the depth of my loving devotion increases daily.

In love, light, and service, here I come Father right into your arms.

On a desk were binders and cassettes. There were “Signs and Sounds on the Inner Journey” and “From Distraction to Divine Experience — Personal Freedom through Innerphasing.” This last one came with a sealed keyword, coupled with a physical action (a hand sign). The text noted, “The deep and powerful effect of innerphasing will become associated by your Basic Self with the keyword and will include all the feelings and body sensations and the state of mental awareness and cooperation.”

I sat in the weaving room, cranking hard on an article deadline as spiritual catharsis took place in the living room below, a cassette-tape seminar in progress. Ethereal sounds wafted into the semi-dark as a poetic voice led the family and their guests in meditation. Formless music rose and fell; mellow words suggested thoughts; somewhere a cat meowed and I gazed out at the full moon over the mountains and the twinkling lights in the valley. Ah, Santa Fe.

Canine Interlude

Down at the other end of some spiritual spectrum was a perverted American Staffordshire pit bull living with yet another pair of my Santa Fe hosts, Steve and Peter.

The dog’s name was Instant, and he was not well. I watched him and struggled to identify a level at which he and I were part of the same Taoist whole. “He’s weird now,” Steve said, “but he’s a lot better than he was. I’m gonna give him until about two and a half. You can’t have much fun with him…”

“Except as an object of derision,” I suggested. We sat on the porch and watched the animal fall in love with a flagstone, one paw holding it down, sloppy pink tongue covered with dirt lolling across the muddy surface, the rest of his wired body tensed and panting. Now and again he would abandon his oral ministrations and go into a frenzy, pawing at the slimy foot-square slab of concrete and flipping it over only to drool on it again in twisted canine passion.

Suddenly he yelped, and with digging motions scooted it across the bare dirt of the yard. His saliva rolled in vile rivulets; his mouth was foamy, the pink gums covered with mud. He looked up at me with small, wide-set eyes, hyperventilating as he made sure I was not about to interfere with his ritual.

“He’s a caricature of himself,” I said.

“I wonder more if he’s a caricature of me,” Steve mused, and then imitated himself with doglike panting: “This doesn’t make any sense, but I’ll do it anyway.”

I continued probing Santa Fe, slowly finding it while counting down the days to the HP’s arrival. It’s no surprise that this is a city of spiritualism, art, eccentric people, tourists, and distinctive culture. The surrounding lands exude mystery and invite contemplation; they may not be as awesome in terms of sheer mass as the Rockies, but they seem more passionate, more subtle.

And they drew me irresistibly into exploration. I camped in Hyde Park, a place of deep sylvan silence and thin mountain air. I traveled the Rio Grande gorge, a dramatic chasm that appears abruptly in a sagebrush plain and startles the eye at every turn. I sat with a dear network friend and gazed for hours into a canyon in the Jemez Mountains, hushed by primordial vastness and ancient depth. The prehistoric rock slowly changed hues as we watched the sun’s angle lengthen, wind roaring through the trees like an invisible waterfall. Calmed by this untrodden timeless perfection, we looked past the canyon to the sparkle of Cochiti Lake and the distant misty bulk of mountains, at peace with ourselves.

Through all this, I was beginning to find another of the things I had been seeking since the beginning of this journey: land of such beauty that it shapes the people who live upon it. Santa Fe does have its neon strip (Cerillos), its infestation of tourists, and its random jerks. But a surprising percentage of the population possesses a sensitivity that gives the place a feeling of life, of spark. From the folks at Pedal Power who went out of their way to help with a Saturday-night breakdown, to the joyous artwork on the adobe walls of an electrical-power substation, this town has energy that almost crackles the air.

It has changed the people, it changed me, and it even changed the bike.

Actually, it was the HP that started it. I fell in love the moment I unboxed my new computer, doubtless becoming a rather unsatisfying house guest in my total obsession. I was much too busy pattering keys in my host’s guest room to share road stories in the living room.

Gawd. A real computer.

I shipped the tattered Queen Anne candlestand back to Ohio and moved into my high-tech executive desk, a place of cavernous storage space and built-in tools. I could calculate, file, and communicate; word-process, schedule, and play. The flip-up screen could display a reasonable chunk of text, and I no longer bumped into walls and knocked things over with every little move. I would now be carrying some fifteen million characters of file storage with me on my bicycle — the approximate equivalent of twenty novels.

But it didn’t stop there, for adding the new system was like that old cliché of buying a new vase for the mantlepiece. The bright new pottery makes the mantle look old, so you refinish it; that shows up the shabby wall, so you re-paper that. Naturally you have to repaint the suddenly yellowed ceiling, and the new living room suite follows within weeks as a matter of course.

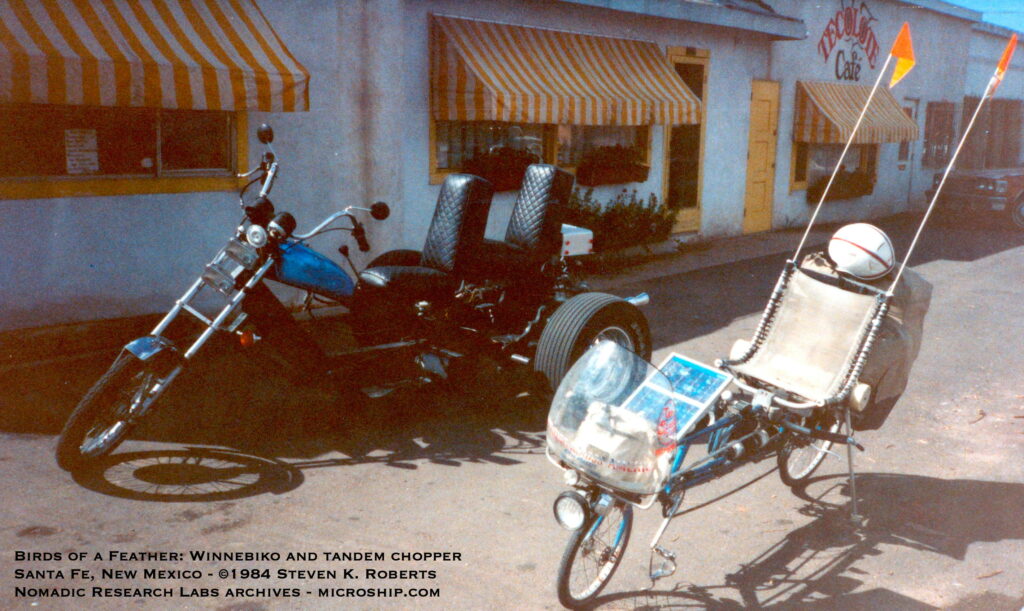

So I replaced the perpetually ailing Push with the latest and slickest in bicycle computers — a Cat-Eye Solar. I added a sexy altimeter to give me feedback on mountain roads, and mounted a compass under the solar panels. A dial-type thermometer completed the new instrument cluster, and as I rode around town I felt like I was in an open-air cockpit: Speed, distance, cadence, time, heading, temperature, and altitude data were all in easy view.

But the snazziest part of all was the new pack. With $4,000 worth of new computer equipment on the bike, garbage bags in the rain would be unspeakably crude. I dreamed of a streamlined enclosure for the baggage area, but assumed the problem was too complex.

Then I met Barbara Thomas, the owner of Suncom Systems. Her fledgling company was in the business of making waterproof computer covers, and when I half-jokingly told her what I wanted she went to work.

It was astonishing. I was reminded of Jack-the-framebuilder who somehow converted lengths of alloy tubing into a sleek recumbent bicycle frame; Barbara took a thousandth of an acre of waterproof packcloth and made it into a form-fitted enclosure. She did this with finesse, style, and a sense of quality that bordered on obsession.

The creation was one of compound curves, strange stresses, velcro, zippers, and attention to efficiency — a complex project that would boggle the average seamstress. Barbara puzzled, made templates, fiddled, fitted, mumbled, ripped out seams, frowned, smiled, stitched and trimmed; somehow, in three days, finishing the job. Phew. The Winnebiko was now a super-sport model, and I even gave it a bath.

Look out, Colorado.

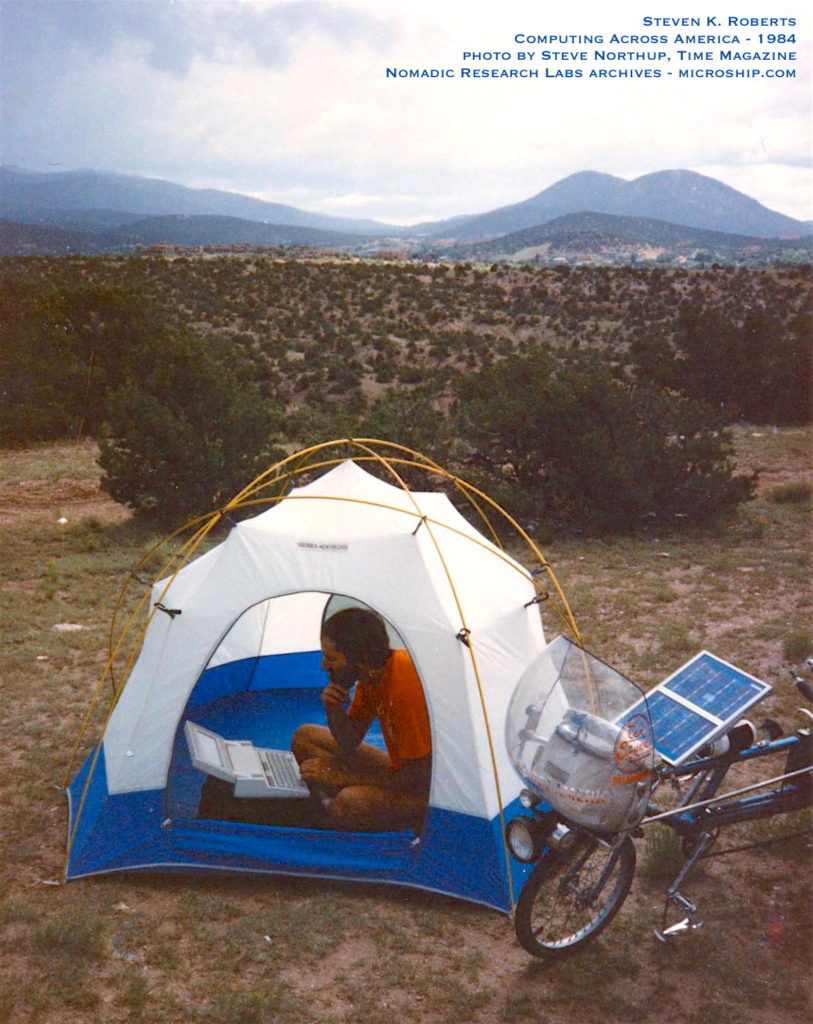

On my last day in Santa Fe, I was working with Steve Northup, a photographer from Time magazine. I described Barbara’s sense of quality, an all-too-rare phenomenon.

Steve grinned. “Hey, you gotta be good to make it in this town!”

You must be logged in to post a comment.