Standing in the Window

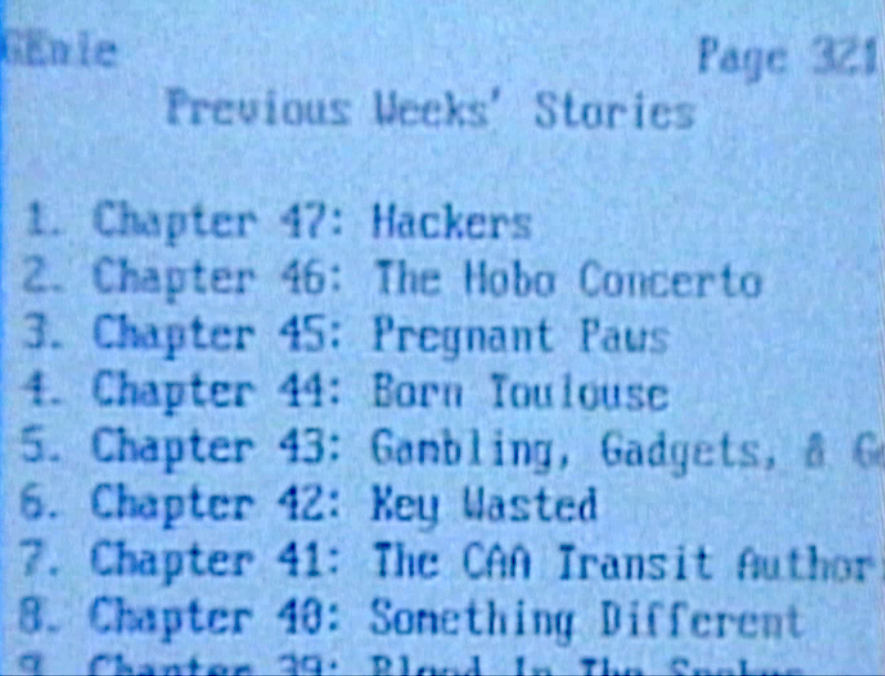

by Steven K. Roberts

Milpitas, California

May 6, 1989

Somebody on the Net recently asked me what my days are like. The popular image, I’m sure, is of a bustling Winnebiko lab with scurrying white-coated technicians fitting glittering surface-mount subassemblies onto a frame of high-tech composites and tightly laced bundles of optical fiber and coax. Surrounded by Sun workstations, I coordinate the efforts of teams worldwide, each pouring thousands of man-hours into modules of plug-compatible perfection while a software team readies the mega-code that will make it all work. The rollout date is circled on the calendar and we’re all feverish, for the eyes of the world are upon us……

Heh. I languish amid the clutter of a household, my back sore from schlepping, my gut swollen from gluttony, my butt blazing red from the Basking Raw-buns syndrome after a day visiting a nudist resort. I whimper, taking in the enormity of the tasks ahead. The Winnebiko II is a showpiece hauled to speaking gigs; the Winnebiko III is a gleam in my tired eye, an abstract vision. Sponsors ship unspeakably beautiful components, and they collect on particle-board shelves and makeshift tables in my lab… each a reminder of a trick unturned, a bit of magic undone. The TO-DO-DO document, 13 pages and swelling, mocks me: I browse it, looking for a clearly defined task. I seldom find one.

Morning, sunny, a perfect riding day in California. I stare out the window and sigh, for the road torments me like a curtainless houseful of playful young women next door to a lonely old man. They breeze about in bits of silk, model new bikinis for each other, oil perfect flesh in noonday sun, wake tousled and touch themselves, linger in the perfumed bath, fiercely love their men with cries soft and kisses wet… while he watches, dying inside, desperate moans catching in his throat, the ache as strong as ever but now an agony of frustration. He’s obsessed; he can’t turn away from the window; frozen dinners burn and telephone solicitors go unanswered when Beauty is afoot. He’s in love, in lust, in pain. He knows they’re killing him with every reminder of the perfection he touched so long ago, but he can’t pull the curtain and hide: the brain is hardwired for sex, by God, and his eyes are wide and staring.

The road is like that, damn her. For six years I have loved her, riding on wave after wave of passion, every turn the kiss of a new friend, every town a seduction, every campsite a tryst, every downhill an orgasm. The cassettes I carried all have the flavor of “our song” — I even stop what I’m doing when I hear the old road music and gaze misty-eyed into the past, my memory an overlay of a dozen scenes linked forever by one musical moment. And the things! Packs, tools, spare parts, toys, even that goddamn shampoo bottle from the Austin hotel… all carry a patina of heart-wrenching memory like the detritus of a deeply-missed marriage.

So with all this clutter in my head, I surround myself with everything I fled so long ago — house, furniture, all the complex baggage of a life fraught with too many projects and dreams. I stand in the window and watch the road wind sensuously up the mountain, loving other wheels, going on just fine without me, and I’m suddenly that lonely old man, condemned to a life of heartache.

!!NO!! I recoil, turning enraged from the window. No, no. Not yet, not yet, you bitch, there’s still some life in these old wheels. Desperate, I grab the phone and call a potential sponsor, leap onto OrCAD and draw a schematic, wipe clean a section of bench and shove a few parts together. But the energy begins to fade… the project is too big. The monitor array can’t be finished because the I/O structure is not defined; that can’t be done until the 68000 is running; that won’t happen until I build the simulator; that won’t work without the monitor array. Aggghhh, hell with it. Another circular problem. Grumbling, I fire up AutoCAD and stare at it, but can’t nail down the console layout until I’m sure to have a CMOS VGA LCD driver that can live on the bus and I’m still early in the CAD learning curve anyway… oh, to hell with that too. I furtively play a game of computer solitaire, feebly scan the TO-DO-DO list, then wander the house, avoiding the window, plopping at last on the bed to stare at the ceiling and hope the phone will ring to jar me from ennui. (The old man tried to get it up and failed; he now stares numbly at the TV with one eye alert to those damn, damn windows next door.)

Maggie wanders in, checks the mirror, then joins me, eyes full of concern. “Having a bad day, dear?” I try to explain that I am, as Dave Wright pointed out, staggered by my own imagination. But I avoid the central issue and concentrate on the critical-path problems, usually coming around to the fundamental truth that I’ve bitten off too many projects for one under-motivated tired guy with a bad back. Working on any one of them by definition means I’m ignoring the others, so I do none of them, seeking instead the quick fix, the easy lay, the Clearly Defined Task. She shakes her head, for this is an old story. She snuggles atop me, long fragrant hair flowing into all my senses, the softness a drug, the love a tonic. Time goes away; I murmur sweetness and doze, problems forgotten until later, always later… but then the house fills with housemates and it’s dinner, talk, distraction, and a few more stabs at the lab before the evening’s drinks fuzz the brain and I give up on one more day.

And as the weeks pass, I watch the calendar, moans catching in my throat. The atlas is a photograph album from an idealized past; I cling to it foolishly and feel a bit embarrassed when Maggie catches me taking it into the bathroom. “Trip planning,” I mumble, but we both know the truth: I’m just standing in the window with a sore heart, watching the road go on without me.

Uh, Fairs of the Heart

Unfamiliar sight, this screen. Or, more accurately, it’s in an unfamiliar mode: text. Normally I see outlines, online sessions, schematics, database records… everything except that which supposedly drives this whole affair. Text. Ah, I remember text…

The delicious transcendence of the well-turned phrase. The mysterious re-creation of moments through an almost automatic sequence of keystrokes: knives twisting, body parts throbbing, icons falling, concepts crystallizing, snapshots of a life snatched from the hurricane and crumpled into a pocket…

Snapshots are the most appropriate medium during this layover, for the continuum, while peppered with transient delights, is itself a numbing routine of gigs and meetings, seduction packages and deadlines, project outlines and piles of hardware. You don’t want to hear about it, believe me: running a high-tech nomad business is much like running any other business, even if the company charter IS fraught with crazy terminology like “weirdness quotient” and “prowling the global neighborhood.”

No, it’s the snapshots you want right now… the liquid, sensual flow of nonstop adventure will resume when I flee this cluttered house and return to the sweet routine of change. Until then, we live for the surprises…

“Uh-oh… I think they spotted you.” Pink-miniskirted Maggie bent prettily to peer through a crack in the bus curtains — the ones hastily installed in the dope-infested alley behind the office of a sleazy West Palm Beach chiropractor so many adventures ago. She turned to me with a worried look. “A bunch of them are headed this way.”

I straightened from the bike’s trailer hitch and looked across the street. Sure enough, from the motley encampment on the San Francisco courthouse lawn — a wasteland of forgotten humanity — came a few eager homeless guys too young to be obsessed with 24-hour scrabbling for sustenance.

“Whoa!” cried a rag-clad dirty blond. “What IS this shit, man?” He shuffled around my bike with a broad gap-toothed grin as others arrived to examine me, the bike, Maggie, and the old school bus that, given the looseness of interpretation and the contrasting character of others arriving for the same computer show, clearly labeled us one of theirs. “You guys travelin’, man? What all these switches do?”

I started to offer a quick, interest-squelching reply, but another denizen of San Francisco streets, young but badly burned out, was fingering my cellular phone beam. His voice rasped slow and slurred from decades of serious drugs and bad booze, and he kept flicking sullen eyes furtively up Maggie’s legs while mumbling… “I got me a radio, man, a fine radio, but I can’t pick up shit in this fuckin’ city, man. What if I get me one o’ these aerials and hook it up, man? Wow… I bet that sucker really pulls ‘em in… I could plug that black wire there right into my radio, man… think that’d pull waves in through all these buildings?” He kept stroking the antenna and looking at Maggie, craning his neck with mouth agape to peer into the mysterious magic bus from somewhere Out There, dreaming of freedom and food and sex and money and the myriad joys of gleaming technology symbolized by the Winnebiko.

“Well, it’s not cut for the right frequency,” I began, realizing the futility of explanation. The first guy was still waiting for a reply, and I turned to him: “Ah, the computers let me write while riding… I travel full time.”

His eyes brightened. So I was a street person too! “Right, on, brother!” He extended a filthy hand, giving me a crazed grin and staring a bit too hard with eyes bloodshot and exophthalmic. “You hangin’ out here, man?”

“Uh no, I’m in town for the West Coast Computer Faire.” I gestured vaguely at Brooks Hall. “I’ve gotta get this thing inside.”

Thus began an interlude of mad contrasts, exactly what we don’t see very often in our tame suburban layover. I maneuvered the bike through streets crowded with tattered beggars and three-piece-suited conventioneers, beautiful women and weathered colorful characters with whole books in their eyes — down a ramp in the earth past convention center personnel who hurried to accost me only to stop short at the incongruous sight. “Now what the hell am I supposed to do about that?” shouted one armed security guard as he reached for the walkie talkie on his belt and ran a few steps after me.

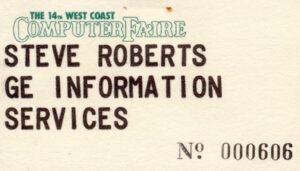

“I’m an exhibit!” I shouted back, refusing to stop. I’d answer enough questions in the next three days — for now I just wanted to lock up the machine and find the hotel. In moments I was rolling through rows of exhibits-in-the-making, computers flickering to life on all sides, the GEnie booth looming huge in the distance with a crown of flashing neon and a giant Air Warrior screen ablaze with simulated flak.

“N4RVE, this is KA8ZYW. Did you make it?” The voice in my ear was a puddle of thin static with a girl in the middle. Somewhere above, she was waiting in the locked bus, the focus of unwelcome street attention.

“I’ll be there in a few minutes… gotta find a place to park this contraption.” Sysops and GEnie-folk greeted me, and before long familiar names were turning into faces in that classic online-culture blend of introduction and reunion.

But the show itself ain’t what it used to be: the bright-eyed tinkerers who once gathered here to pass the pipe of technoid passions have, for the most part, been swallowed by corporate culture. The wizardry-intensive entrepreneurial firms are elsewhere, and the show, though a success in purely numerical terms, was more a small-town COMDEX clone than a gathering of wizards. GEnie’s booth was the largest of all, packed for three days by visitors eager to sip freely from online terminals and ask the standard suite of bike questions (the most remarkable of which was: “What are the handbrakes way back here for? So if the guy in the back don’t like what the guy up front’s doin’?”)

But what gave the visit true color, for us trade-show-jaded nomads, was the close-up and frightening look at this city. San Francisco has always been a mecca of street culture — an intense tangle of human genotypes covering the full range of every spectrum from the moral to the monetary. We would transition with an abrupt shock from hotel to street, staggering a bit through the revolving door as opulence gave way to squalor, as the sparkling spacious gracious guts of the Regency Hyatt were replaced by dirt, honks, extended palms, and a coarse melange of street language. From luxury to paranoia in an instant.

Of course, any big-city hotel gives that feeling: you can step out onto the 42nd RushMarket maelstrom from some of the ritziest places in the world. San Francisco is laced with beauty and tragedy unlike any other… from the dazzling romantic skyline, sparkling in our sunset view from the 18th floor corner suite, to the quick-stepping unease of rough street life where you grip your 2-meter handheld transceiver like a weapon, hoping they hear the crackle and think you’re a cop…

But partying and exhibiting with GEnie was, as always, a pleasure, with Grand Marnier soufflé relaxing the mind after days of booth frenzy (where one fellow extended $10 for a book only to pull it back and ask, “is General Electric going to get any of this? I’m boycotting them for their involvement in nuclear power…”) The street people had no such compunctions as, much to management’s dismay, they found the discarded plastic GE literature bags to be a stylish personal accessory…

Every show is different. WCCF, though lean by the old standards, still presented us with a population that’s reasonably literate and conscious of computers — people there were generally intelligent and there were many whose demeanor bespoke true brilliance. But J. R. “Bob” Dobbs of the Church of the SubGenius once observed: “You know how dumb the average guy is? Well, by definition, half of them are even dumber than THAT.”

Corroboration of this is easy. Just exhibit a complex and exciting machine at a show that attracts the general public, outside the mainstream of technoid metropolis.

I’m writing from a chair in the Pleasanton sun. A woman has just stopped, taken in the trailer behind my bike, and cried, “Oh, you have puppies! I love puppies!”

Another crossed this concrete patch with an unhappy kid straggling behind her, amusing himself by balancing on a fat electrical cable feeding the stage area. “Get off that!” she screamed. “You wanna get electrocuted?”

This is a weekend like the old days, in a sanitized sort of way: the general public owns my time, and thinks nothing of interrupting earnest keytapping to mouth the standard suite of level-one questions. It can be irritating, but I suppose I shouldn’t complain: every now and then they fish in their wallets to find a ten-spot for a copy of my book. Hell, that’s why I’m here at a fair instead of down in the valley trying to work.

Yep, it’s a weekend of noise, here in Pleasanton, California. There’s a home/garden/outdoor/random-junk show going on, and I’ve abandoned the complex struggles of Winnebiko III work to trade precious time for precious money. My heart’s in the lab; my brain’s in this chapter; my body and bike are on display before the general public.

And that’s part of the trade-off — the part I keep forgetting when I lay plans for future wandering. The adventure, the technology, the change, the new friends, the physical delights of cycling, the complexities of life in Dataspace… those are all deep pleasures that make every sun-drenched day as much a source of chest-tightening <pangs> as a glimpse of sweet beach flesh. The traveling urge is potent. Yet with every weekend foray from our suburban hideout into the public eye, I am reminded of the frustration that comes from trying to communicate across an infinite gulf. As the system grows ever more complex, the task of explaining it to the curious gets seriously overwhelming… especially when some guy points at the machined Lemo waterproof connector on my helmet and asks, “now what the heck ya doin’ with a dental drill up on your hat here?”

Yes, even in California. No part of America, I’m sorry to say, has the monopoly…

But there’s more to life these days than the occasional weekend ordeal. We’re in the thick of it now: we’re suburbanites. You ever wonder what nomads do for vacation? Rent houses in the ‘burbs, have friends over for barbecue, dream of the road, and try not to go mad, that’s what.

Actually, it’s not quite as normal as it sounds. Our household in the southeastern fringe of the Valley is a strange place, with noises, accessories, and usage patterns that set us apart from our commuting neighbors. At 2 A.M., you might find the Winnebiko parked in the middle of the street, a 10-foot satellite antenna array clamped to the trailer and aimed skyward at OSCAR-13, with an erstwhile nomad nearby hunkered over a pile of communications gear destined for bike installation. “You’re on a bicycle?” comes the incredulous Tasmanian voice through the static, via a 44,000-mile round trip path. “Only in America…”

Inside, the house is amalgam of R&D laboratory, bike shop, playground, art studio, and party place. What once might have been a living room is now a lab, buried under layers of technoclutter and astrewn with computers. There’s a robust H-P CAD system, four DOS laptops, two FORTH development systems, and more random micro-based circuit boards than I can count. The space is already proving to be inadequate, and we’re looking elsewhere in Silicon Valley for a laboratory sponsor.

The “family room,” shared by the five of us, is the place for video, audio, music synthesizers, books, and miscellaneous toys. The fireplace is surrounded by an eccentric array of decorations: a battered sousaphone, an antique child’s bicycle, a Bausch & Lomb stereo microscope, a bonsai tree made of machined laboratory hardware, a bright red fireplug, and an aluminum foil sculpture.

Elsewhere, the house varies in style. There’s Chip’s studio, a busy place hung with dragons and fantasy; Dave’s garage shop, filled with smelly fiberglass projects and high-speed human-powered vehicles; our bedroom, half office and half bike storage; and a few other places to sleep or hide. There are the requisite cats, of course, odd artworks, and a little blue light-activated siren that migrates from hiding place to hiding place as the denizens of this strange retreat come up with new pranks to pull on the unwary.

It helps sometimes to think of this as just another part of the lifestyle sampler.

Of course, there’s no reason why a long layover has to rob life of adventure; there’s always enough going on to keep things on the edge of madness. Take the last night of our Pleasanton excursion, for example…

“You guys want to run into town for dinner?” This from one of our fellow exhibitors at the Alameda County Fairgrounds — an ebullient Spanish gambler with fast boats for sale and a Vegas trip to raffle off. Por que no? We piled into his car and motored off into the night, only to be pulled over by a local cop after breezing through a stop sign. Oops.

Bathed in the police spotlight and intermittently illuminated by flashing blue, I waited in the front seat, squinting bemused through the passenger-side mirror at the encounter behind us. I caught words of denial, words of outrage, words of mollification — then the cop appeared at my window with the flashlight. “What’s your buddy’s name?”

I searched my memory, remembered a business card, told him.

He walked away, and in a flash our friend was up against the car, handcuffed, and frisked. The cop reappeared at my window. “I don’t like being lied to. He has some warrants out and told me he was his brother, but he couldn’t seem to get the birthdate right, so I’m arresting him. He says you can take his car and go on to dinner.”

And so there we sat by the side of the road in a strange town, watching the cop roll into the night and wondering whether to risk driving the unregistered New Mexico car. Easy decision: back we went to the familiar tan bus, which, oddly, still seems to feel more like home than the Milpitian villa.

It goes on. We did a filming last month for Japan’s NHK television (something like our PBS) — two days of simulating road life for a crew of four — only one of whom spoke English.

“Now you must camp,” said Atsuko with a smile. “And Maggie, you make the tea.” We had struggled the bikes to a hillock near the Calaveras reservoir, and spread the tent fabric in wet grass to keep our bodies dry.

Maggie dutifully fired up the camp stove while I browsed the atlas and idly tapped on the laptop. The camera recorded every moment of our simulated reverie, and when the tea was ready it smoothly followed the cup from her hand to mine. Ignoring the lens, I sipped quietly, waiting for my moment.

As soon as the cameraman panned to Maggie, I pulled the string out of its staple on the teabag, hid the bag itself under the edge of the tent, and poked the string in my mouth with the tag hanging in my beard. I munched contentedly as the camera panned back again to me, then slowly extracted the string and mimed a healthy swallow. “Ahh, tea…” Japanese viewers will be scandalized by bizarre American tastes, but if they elect to attempt the practice I do hope they use teabags without staples.

Enough. I’ve delayed this update too long to have a hope of catching up — the Silicon Valley electronic surplus culture surrounding Halted, the radiation detector, the ferret, the midnight feeding frenzies, the mountain bike forays for soft adventure, the idyllic nudist park, the countless crazy details of life here. The important stuff will emerge eventually as these asynchronous reports continue — and yes, despite the sense of despair that opened this story, work IS progressing. It’s going slowly, to be sure, but the Winnie will roll again… hopefully with me perched happily upon it, all brain-interface channels active.

In the meantime… cheers from the nomadhouse!

You must be logged in to post a comment.