The Idea is Born

Computing Across America, Chapter 1

by Steven K. Roberts

Dublin, Ohio

March 15, 1983

What’s the matter Steve? You going to be a bum all your life?

— Phyllis Roberts (my mother)

Suburbia is not a place; it is a state of mind.

It has little to do with the section of town you happen to live in; it has nothing to do with the size of your paycheck. It runs rampant in some places and lends its name to whole neighborhoods, but the meaning of the word “suburbia” has outgrown the civic jargon of which it was born.

You live in suburbia when the cycle of work and play becomes dangerously unbalanced in favor of work. You live there when your success is measured by dollars instead of happiness, when the demands of your lifestyle force you into an ongoing upward career struggle. And you are suburbanite when change, evolution, and growth start to sound more like counterculture concepts than the basic objectives of daily living.

Suburbia can happen anywhere, for it has almost become the default mode of this insane world. It can happen to anyone, and it happened to me.

I was slow to notice, of course. I spoke glibly of the deepening economic spiral of my life in terms of “cash flow” and “debt capital.” I waved at my Dublin, Ohio, neighbors, but after four years didn’t really know them. I worked on my writing, calling it “freelancing” while requiring an absurd $3,000 a month to stay afloat. I wasted time endlessly yet was unable to take a vacation, for recreation was just a time of nervous guilt over uncompleted projects.

Dissatisfaction mounted. I kept rearranging the office and drafting business plans — but the stagnation deepened, punctuated by dreams of escape and travel. I fought my way from one monthly crisis to the next while managing to look successful to the rest of the world.

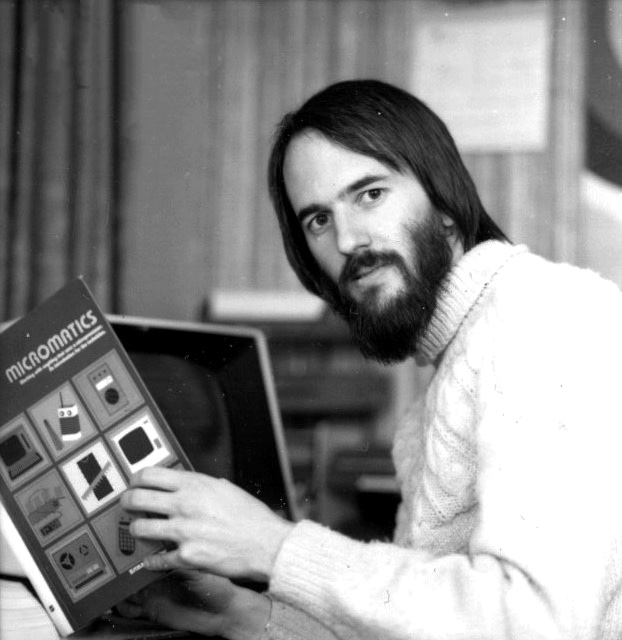

“Hey, wow, you’re a writer!” someone would say. “What kind of stuff do you write?”

“Oh, mostly high-tech — three books on computers, magazine articles about artificial intelligence and micros, stuff like that. I also do technical writing and consulting for a few corporate clients.”

“Man… what a life. I really envy you. It must give you a lot of freedom.”

“Yeah, freelancing is a license to be a generalist. There’s nothing I’d rather do for a living.”

(Except play.)

One afternoon in the spring of 1983, I went for a bicycle ride with Walt Spicker, an engineer at the Anatec division of Atlantic Richfield. For a year or more the company had been my sugar daddy, paying me a healthy hourly rate to write documentation and sales literature for their line of industrial process control systems. Walt and I had struck up an early friendship, and we crossed paths every few days to cycle the lazy farm roads, swap engineering war stories, and swill gin-and-tonics until we began stumbling into each other and talking about women.

Off we went into the flat corn country west of town, pedaling away the routine frustrations while idly discussing the latest hirings and firings. We were on Avery Road, an hour into the ride, when something strange appeared in my rearview mirror and began to gain on us.

I didn’t know yet that my life was about to change its course, that a nexus was upon me.

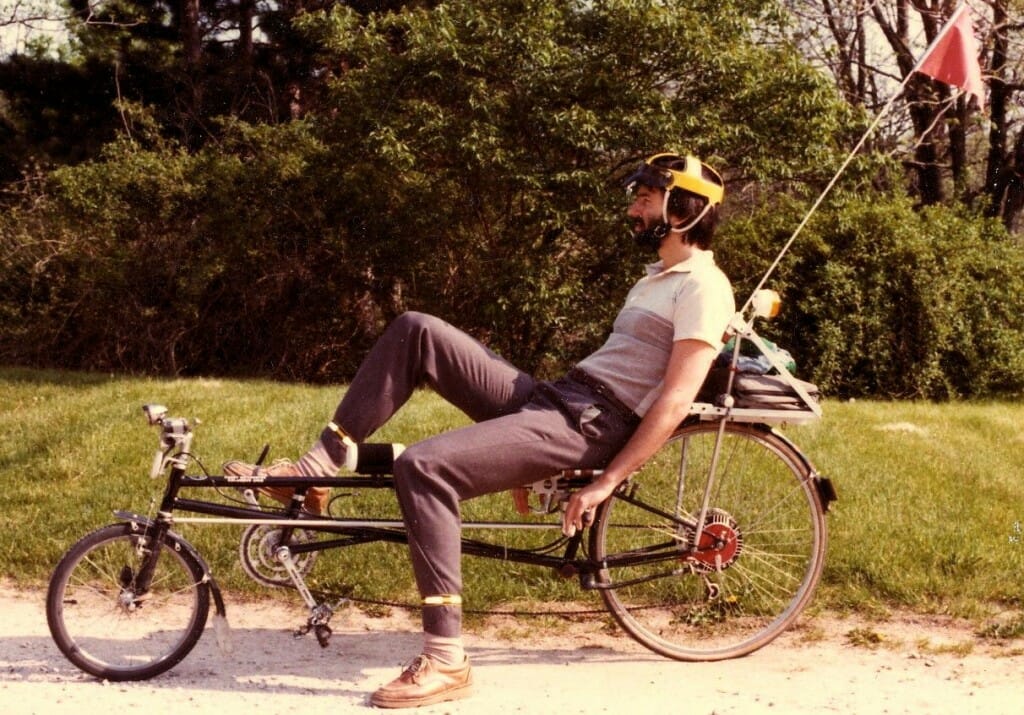

The apparition — half human, half machine — slowly grew in the mirror. “Walt,” I said at last, “I think were about to be passed by a recumbent.”

“Aw, Roberts, the election’s not till November.”

But the image kept getting larger, soon revealing itself to be a distinguished-looking graybeard on an Avatar — Robby McCormick riding a low-slung black bicycle that looked like a sleek lawn chair on wheels.

He pedaled comfortably alongside us, gnarled legs out in front of his body, weathered hands resting on grips below the sling seat. He grinned and called a greeting to us two youngsters hunched awkwardly over old-fashioned ten-speeds.

We plied him with questions. “How much faster is it? How about stability at higher speeds? How is it for touring? Is visibility a problem? How much does it cost? Are there any discomforts? Ever have trouble with dogs? Do you ever actually get anywhere, or do you spend too much time answering questions?”

Robby chatted easily as we cruised along, informing us that in the three years he had owned Avatar serial #1, he had put over 18,000 miles on it. No more back problems or strain: this energetic 65-year-old was averaging more than 500 miles a month and loving it.

I started dropping hints, and he finally asked with a laugh if I’d like to give it a try. We swapped machines.

I pushed off with my left leg and immediately realized just how alien a balancing act this was. A bicycle? With a succession of wild over-compensations, I swerved from one side of the road to the other, more than once dropping a foot to the pavement to prevent the embarrassment of crashing this enchanting $2,000 instrument.

But then it started to make sense, and the corrections became smaller — a biological closed-loop control system being brought into tune. Within moments I was exploring the gears and zipping along with a healthy tailwind, exuberant, excited, moved even to whoops of delight. Instead of perching on a tiny hard seat, I leaned back in a comfortable sling; instead of having to strain my neck to look around, I could take in the scenery as if relaxing in a rolling easy chair (a bike-a-lounger?). My hands hung at my sides, resting lightly on responsive handlebars.

It was beautiful.

Robby huffed alongside on my red antique, looking a bit absurd on the giraffe frame (I’m six feet four). His hips swiveled in a parody of the hula while I cruised in luxury.

“Like it?” he asked.

I laughed out loud. “Like it? I think I’m in love! Where do I sign?”

I climbed back on my suddenly boring Miyata and rode along in silence while Walt gave it a try. Like a tiny revolution, something was fomenting in my brain, something radical and insane and somehow exactly right. I was almost afraid to recognize it, but a great understanding was dawning; with a sudden maniacal grin I poured the power to the pedals and left my friends far behind.

It was the memory of a grand scheme, the almost violent recurrence of a fantasy I had entertained off and on for a decade. An idea was crashing the quiet gates of suburban complacency, tempting me with sweet mad images of exotic adventure. This would be my way out: I’d get rid of everything, move to a recumbent bicycle, and travel the world.

Yeah…

Actually, I had tried before. Over the years I had collected travel brochures, maps, and random bits of touring gear. At times of stress the idea would resurface — usually dying quietly after a few minutes thought; sometimes sending me on month-long dead-end projects of trip preparation. But always there had been one basic problem: no money.

Well, there was still no money — but I had a plan.

After Robby bid us farewell and turned south toward his Arlington home, Walt caught up with me. “Alright, Roberts. What the hell kinda crazy caper you cooking up over there?”

“Why, Walt, what do you mean?” (Was I that transparent?)

“I know that look in your eyes. You’re either thinking about starting a business or planning on writing a book. And they probably both have something to do with recumbents.”

I spoke through my panting with quiet conviction. “Walt, I’m never spending another winter in Columbus. I’m going to build a recumbent and take my writing business on the road.”

“Yeah, right. I can see you dragging an office around the country in a bicycle trailer.”

“It wouldn’t have to be that big. All I need is a portable computer and a base office here in Columbus. I shouldn’t even have to carry a disk drive, since I can transmit copy to my home system, whenever I get done editing it — and I can use the CompuServe network to take care of daily business communications. Walt,” I added, looking around at the beginnings of sunset coloring the sky over bare cornfields, “I really could live like this.”

“I’m sure you could. Until the money ran out.”

“I’m serious.”

“So am I. Look Steve, in the year I’ve known you I’ve heard more harebrained schemes than I can even remember. There’s only one thing that’s gonna get your ass outta debt, and that’s work.”

“I’m talking about working.”

“No, you’re talking about playing — which ain’t a bad idea at all if you can get some sucker to pay you for it. But don’t hold your breath.”

“Man, it can work. All that overpriced house in Dublin is good for is giving me a place to keep my junk, of which I have far too much. I’m a struggling single writer — why the hell do I need a three-bedroom ranch on an acre in suburbia?”

He took a swig from his water bottle and replaced it in its cage with nary a glitch in his pedal cadence. “I can’t argue that point, but I still don’t think you’re gonna pull off this crazy trip. I give you about a week to get over it.”

“I’m serious about this one, Walt.”

“I’m sure you are.”

I grinned over at him. “Well then, how do you feel about getting together on a recumbent-creation project?”

“Now that might be interesting. Wouldn’t mind having one o’ them things myself!” And with a hearty wave, he veered off for dinner, pedaling alone the last mile to his beautiful wife, devastatingly cute little girl, and comfortable home.

I rode slowly back to my cluttered house: a place of unfinished projects, overflowing office, dirty dishes, tall grass, dust, and around-the-clock computer-cooling fans. I left the bike in the yard, walked in, grabbed a beer, and slumped on the couch with the cat on my lap. In my thoughts I soared down mountain roads, sailed along in balmy ocean tailwinds, and cavorted with campus beauties all across the US of A.

My present life felt like prison.

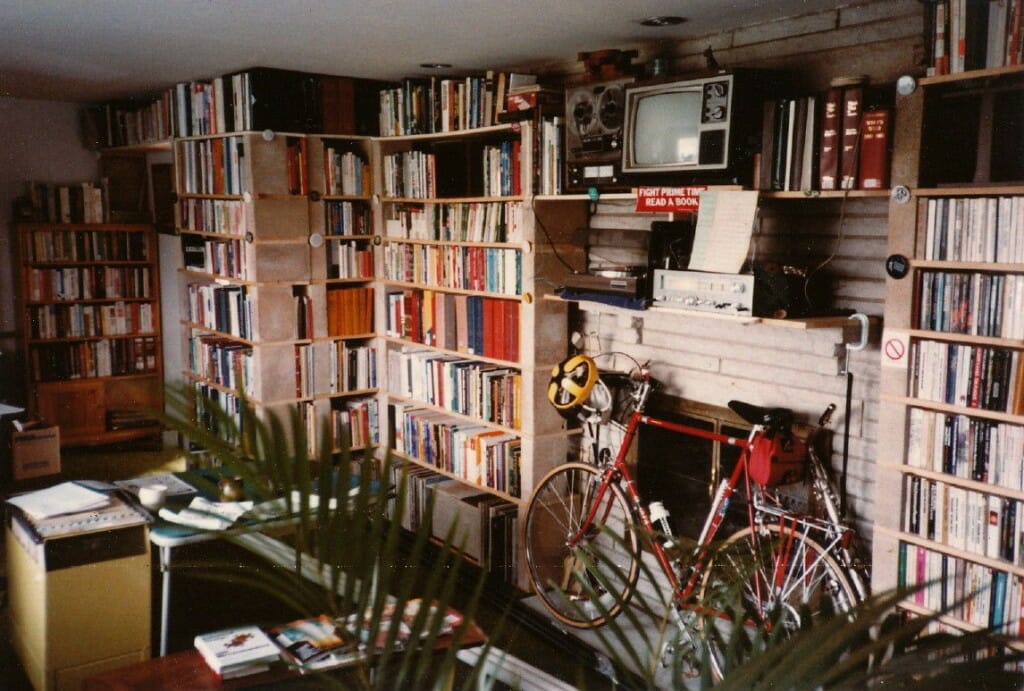

I was ready to escape. The certainty was growing so fast that it frightened me. For most of my adult life I had been a homeowner, an entrepreneur, a technophile, a collector of trappings. My living room was office and library — a place of file cabinets, thousands of books, photocopier, computer systems, steel desks, and clutter. The rest of the house was crammed to the rafters with tons of crap, none of which seemed at all important in the context of life on a bicycle.

I would have to trash my lifestyle while still living it. The Idea was only ninety minutes old and I was already cataloging the myriad tasks that lay ahead.

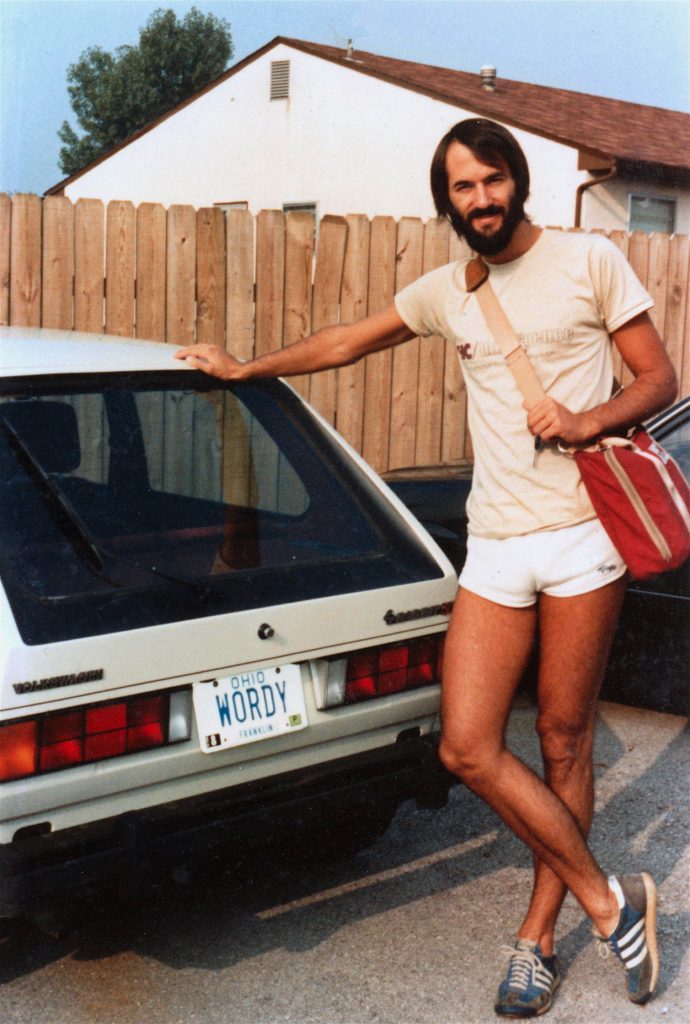

The phone rang. A willowy friend from Marysville invited me to a cookout in the country, offering that always welcome alternative to work. Without so much as a nod to the looming deadlines, I showered and dressed while fantasies of the road swirled in my head — along with the rapidly growing certainty that this could actually happen. I climbed into the leased Rabbit GTI (complete with a vanity license plate: WORDY), and drove through Dublin’s cute old-fashioned shopping district, then past the gas stations and onto the highway.

There. On the radio. I turned it up.

The voice was haunting, lonely, free. A guitar, articulate and clear, spoke with a sort of measured mournfulness yet came across as energetic, the blues of the highway, a perfect complement to The Idea. It was the birth of a theme song. I turned it up further; the song was conjuring poignant images of travel.

Robert Plant called eloquently to the traveler awakening within me, and bid him arise and flourish. I glanced up at the Escort radar detector to make sure it was on, then pushed the speedometer to eighty, high on movement, high on the dream, high on US Route 33. The miles drifted softly by… and I could have driven forever.

But here was the Marysville exit, and there was Madelaine, and before long the evening was in full swing. Small talk and big talk; barbecue and video games; a country house and strangers meeting. But as the night grew colder, action withdrew to the living room and the keg, focusing the voices and stinging cigarette smoke onto far too small an area. Impatient with the oppressive air and bored with conversation, I strolled alone to the campfire.

Perched on an upended piece of cordwood, I gazed into the dancing flames. I could have been anywhere. I fancied myself alone in the high Sierras, contemplating the ancient mysteries of fire after a hearty freeze-dried meal.

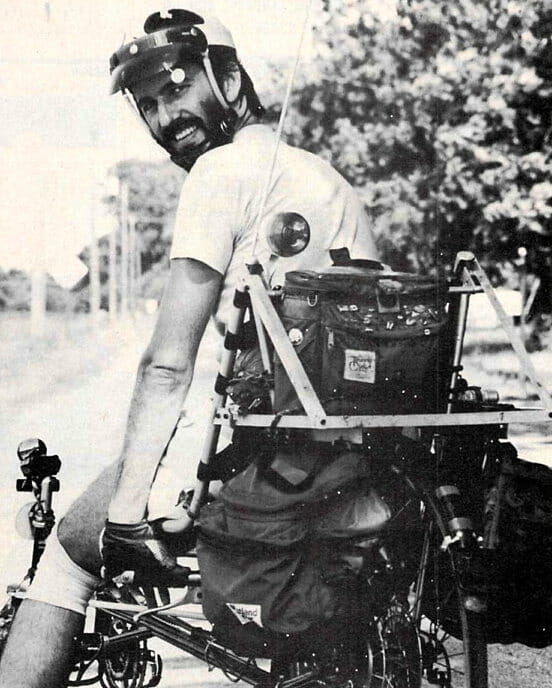

Yes, goddammit, yes! I would sell the clutter of my life. I would unload it all with a massive garage sale, then use the money to build and outfit a recumbent bicycle — including a portable computer for word processing and communications. A base office would be necessary, so I would find an assistant and a suitable workplace. I’d develop some new magazine markets, locate a New York agent to help line up a book deal, and, well, everything seemed so clear there in the flames that I was impatient to get on with it.

I wanted to escape as soon as possible: I sat in the starry night and visualized myself rolling off into the West on my tattered red swivel chair, dragging the clinking remnants of the bonds that had kept me chained to my desk for so many years. A laptop computer with a modem would be my link to the universe — inhaling and exhaling mail, articles, and maybe even a book.

Now and again people dropped by my little oasis of Deep Thought on the edge of the tame Ohio woods — perhaps bringing me another beer, perhaps just curious about the silent brooding back hunched alone by the fire out there in the dark. How could a guy stay so long away from this six-foot longhaired beauty giggling at a Space Invaders video game? Who is he anyway? He’s sure an antisocial sonofabitch…

I sipped my beer absently, thinking about bicycle lights and sources of electrical power (solar? hmm…), camping gear, file-handling, small-town cash transfers, frame geometry, and how the hell I was going to get everything ready before winter. Sometimes I just visualized a US map and dreamed; sometimes I frowned at the immediate and difficult problems. But never did I question the Idea; I just tossed another log on now and then as the hours passed.

Back home alone at 3 a.m., I blearily looked about in my garage. There it was, buried in mostly unnecessary junk and harboring a few spring spiders. There. Its legs were bent, but it would do for starters. I dusted it off and refreshed the phone number with a black felt pen. Leftover from the last attempt at escape, it was about to sway once again in the gusty breezes of passing cars.

Holding the flashlight in my teeth and shivering with more than chill, I planted the sign in my front yard:

FOR SALE BY OWNER

764-8836

Preparations had begun.

Continue to Chapter 2…

NOTE: I had great plans to do this as an audiobook, but the above text was the only chapter I managed to complete in the first pass at the project a few years ago. If you would like to hear me read it (with a few added sound effects), you can find it here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.