Computing Across America

Computing Across America, Chapter 0

by Steven K. Roberts

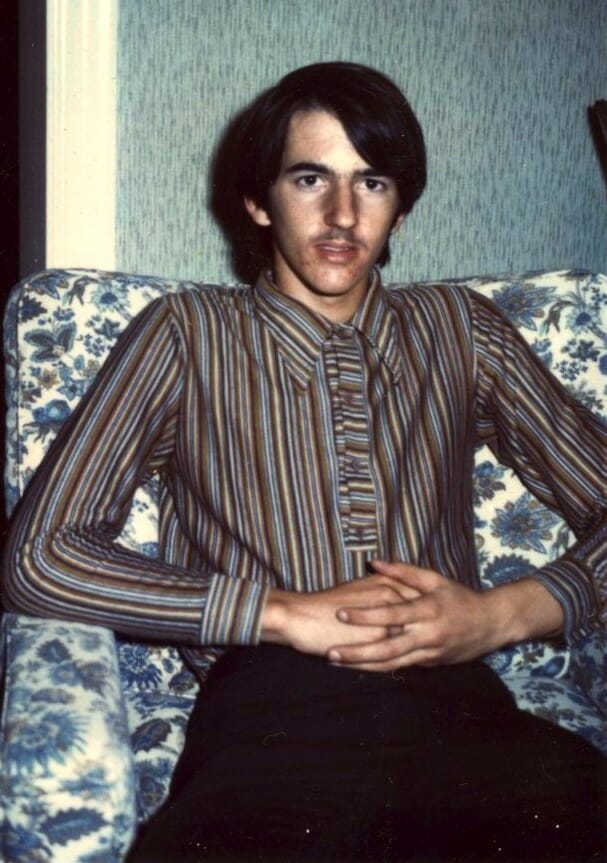

1952 to 1983

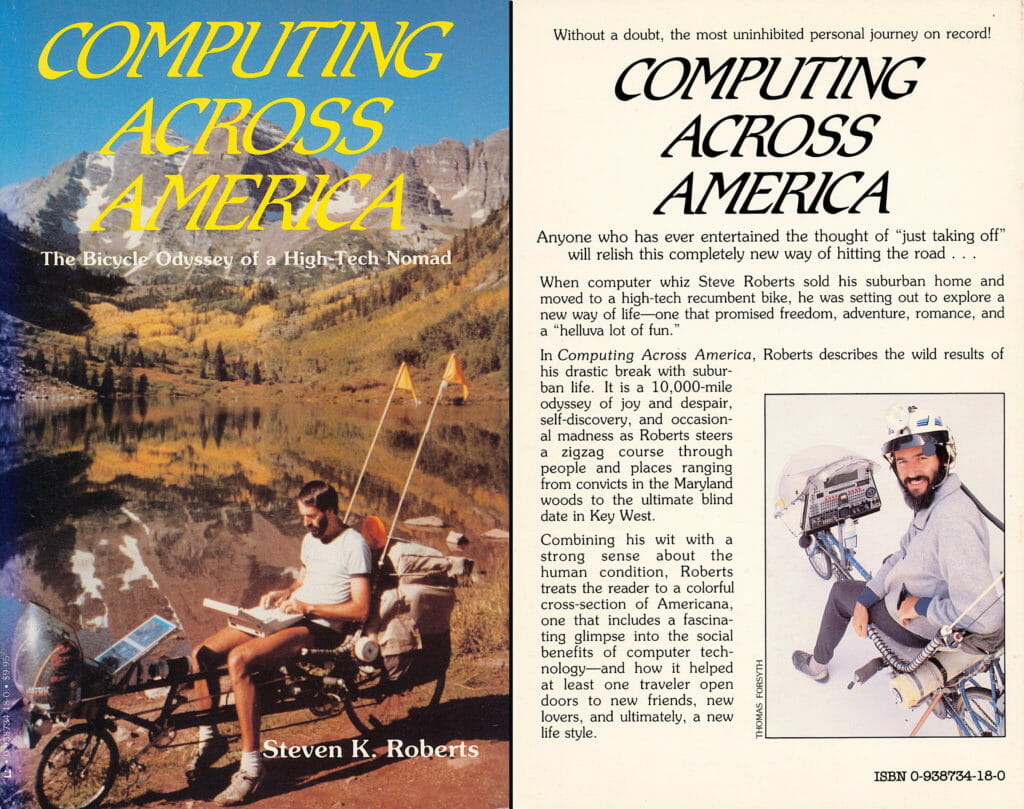

From 1983 to 1991, I pedaled around the US on a computerized recumbent bicycle while living in the emerging online networks… in the process becoming the first “digital nomad” and sparking fascination with mobile connectivity. This is the backgrounder and introduction to Computing Across America, long out of print but about to be re-issued in hardcopy and eBook versions. A concise version of this story is now a video, just under 7 minutes:

The stories are interleaved in the timeline with media coverage and other material, but at the end of every chapter there is a “CONTINUE TO…” link that will let you skip all that and read it like a proper book. But the best way to read this is to subscribe for free to the Substack serialization, which is becoming the new primary source for the hugely expanded book — scoped to include all three bike versions and the full decade of adventure.

Subscribe to Computing Across America

The Prehistory of a Technomad

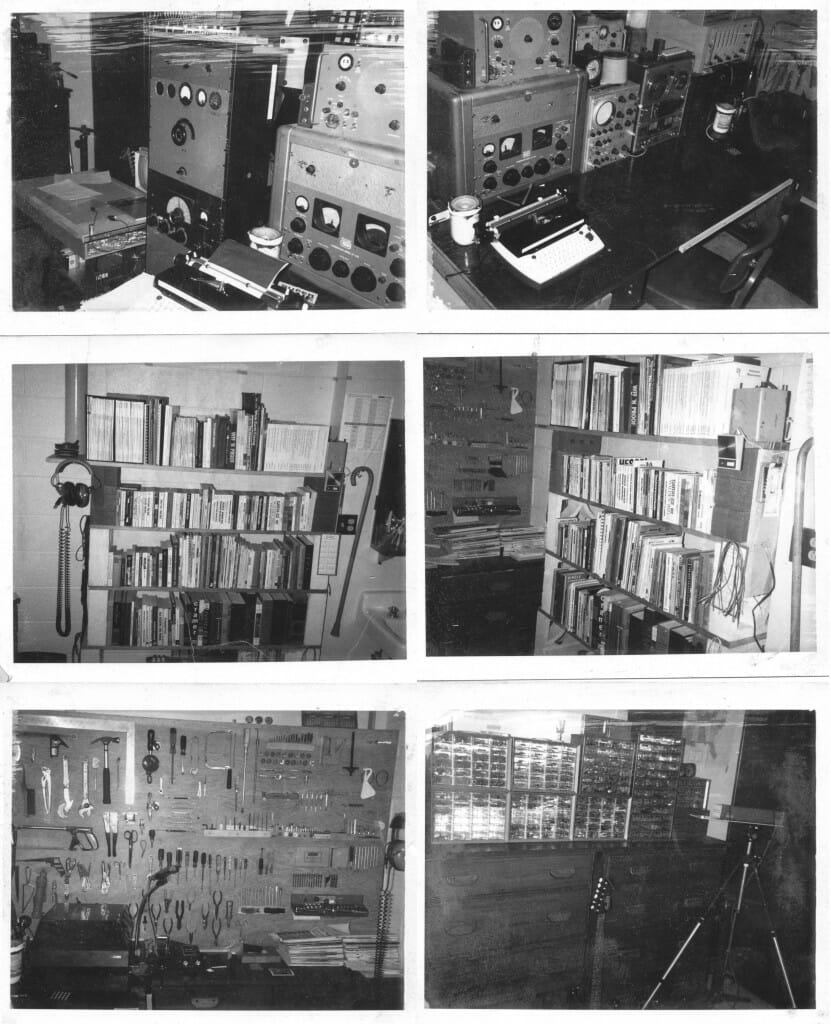

Electronics was passion, obsession, raison d’etre. My identity lay in my basement laboratory; my happiness was a function of acrid solder smoke, blinkenlights, clacking relays, and that sweet mysterious crackle of shortwave radio. When I was 9, I had a contest with my friend Rusty, a chemistry fanatic: we each had a week to write down all the words we knew (or could find) in our respective fields. Pentode. Grid-leak. Crystal. Nixie. Hollerith. Ahh, the early ’60s in Jeffersontown, Kentucky.

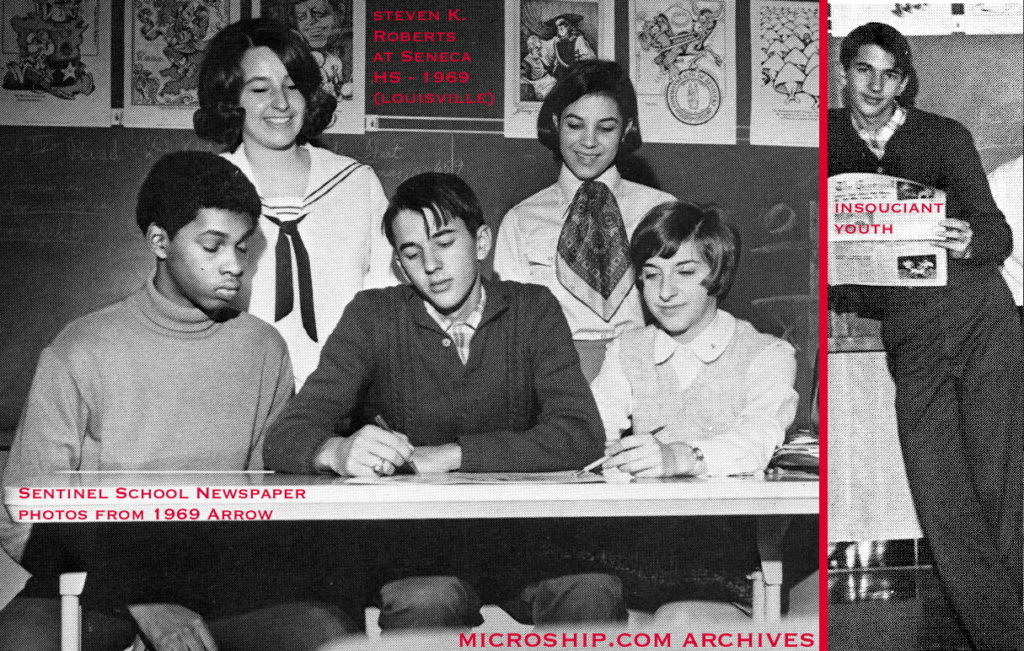

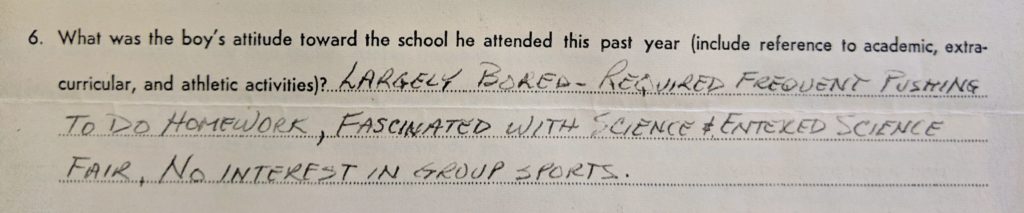

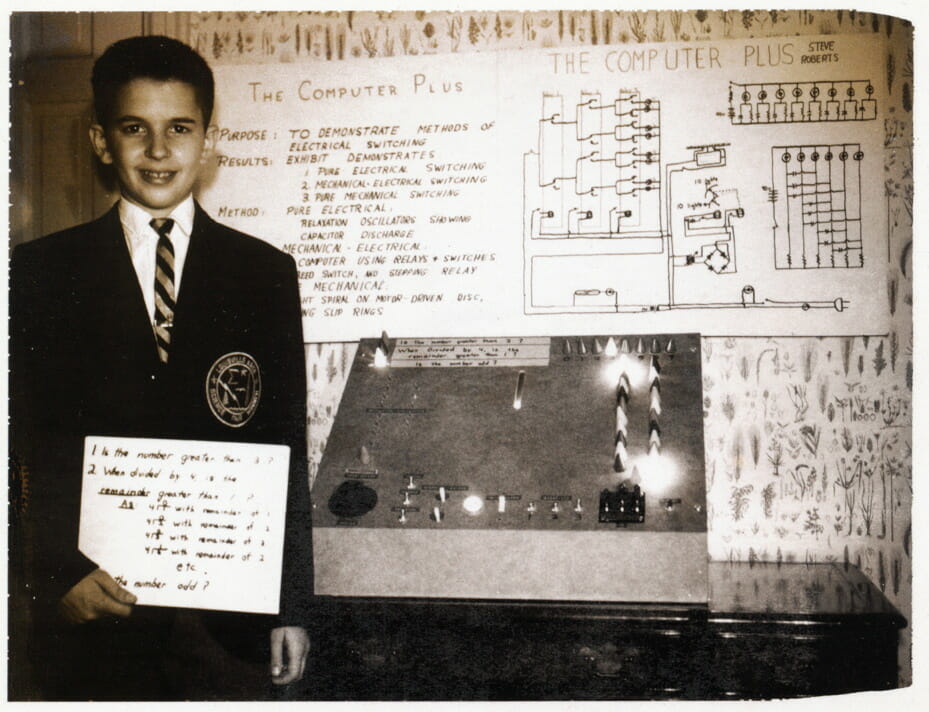

By the time I was 12, I was a ham radio operator known as WN4KSW, a skinny burr-headed prisoner of school. I was theoretically a smart little bugger, according to test scores, yet I kept hearing that I had attitude problems and wasn’t working up to my potential. With the exception of science fairs, my academic performance was apparently disappointing to authority figures.

Oh well. I didn’t care: I had a secret life.

School received the minimum attention required, which wasn’t much. My real life was too important to dilute with homework: I was obsessed with relay logic, my lab, and the vague notion that if I prowled the magical world of electronic surplus with enough finesse, I might even be able to cobble together a computer with a few thousand 12AU7 triodes and an air conditioner. I amused myself with microphones in the ductwork and a parasitic phone line routed through an old black-crackle 19-inch equipment rack, listening to domestic goings-on by way of an 8-ohm primary coiled around the lab and an amplified loopstick antenna on my headphones (a primitive wireless audio system).

Year after year I tolerated the time-waste of school, accepting patriotic brainwashing and sanitized history, superficial science and anachronistic literature selections — living not for girls, grades, and the gridiron but for electronics, science fairs, and dreams of my future laboratory. I was a social outcast, for my adventure was measured in volts, not adrenaline. When neighborhood bullies soaked my books with squirt guns one day, I ran home and attached a battery-powered 14,000-volt supply to a pair of squirt guns mounted side-by-side on a wooden stock… with salt water as the conductive ammo. As long as both streams hit someone before degenerating into droplets — WHAM!

My relationship with the neighbors subtly changed.

Empowering stuff indeed, but most seductive of all was radio… for it connected me to the outside.

It’s like a flashback now, recalling the chirpy Morse code of my unbuffered crystal oscillator built on a chunk of pine, the deeply imprinted smell of solder and flux vapors, and the magical noises emanating from the Star Roamer — as well as the Heaths and Hammarlunds that followed. Other people, other tongues, strange sideband squawks, political realities and cultural attitudes utterly unlike the Huntley-Brinkley Report that invariably accompanied dinner to the strains of Beethoven’s Ninth. I spent years gazing through this electronic window and building my tools; like the railroad tracks that passed near my house, radio became deeply symbolic of escape and movement. My physical adventures were confined to rural bike hikes; in my head, I could cruise the universe with a skyhook and a powerful collection of instruments ablaze with Nixie readouts, backlit dials, dancing meter needles, and round green CRTs.

When I was a senior, I finally made it to the International Science Fair — a holy grail — with a homemade speech synthesizer. Having hit dead ends with other approaches after three years of frustrating work (tape loops, LC tank circuits, discrete transistor filters…), I built a working acoustic model of the vocal tract based upon X-rays of my own head. It even had a voice-change problem.

Graduation, anticlimactic and vaguely embarrassing, occurred in 1969 — when I was 16. I was academically ordinary, ranked in the middle of my class after skipping the sixth long ago. There was such a gulf between learning and school that I responded with less than adequate concern to my parents’ repeated accusations that I was still not working up to my potential. It was an old story by then, though it did have its moments.

I arrived at Rose Polytechnic Institute wide-eyed, heavy-laden with gadgetry and school supplies, ready to plunge into every college cliché I had ever seen in the movies. Philosophical bull sessions, scientific investigations of beer and other interesting substances, the mysteries of girls at last unveiled, haze-crazy fraternities, brilliant and slightly mad profs, all-night test-cramming sessions, eccentric nerds, emotional moments of discovery, huge computing machines, and through it all that magical rarified air of academia, of knowledge. I got goose bumps all over my alma mater just imagining the richness and camaraderie of college life.

But engineering school turned out to be like going to art school and learning to paint by numbers. The infinitely interrelated universe was segmented into “subjects,” taught in isolation, out of context — despite the fact that humans are associative systems and generalists at heart. “Remember this, and this, and this; don’t worry, Steve, it will all fit together someday.” Nonsense! But there was something more insidious still: the motivation for learning was not curiosity, but fear of failure. That had the effect of reducing the educational process to a succession of panic-stricken study sessions. Learning was just the incidental spinoff of staying out of trouble.

Besides… it was 1970 and getting high was much more fun than studying. It even promoted that sweet illusion of wisdom, making it easy to feel good about donning a headband and quitting school halfway through freshman year. Before I knew it, I was on the road — waving my thumb from interstate shoulders and living out of a blue backpack emblazoned with the icon of peace.

As fun as that sounds, I soon tired of penniless drifting and began sampling jobs. I grew tan and strong as a deckhand on barges in Illinois and Minnesota; I briefly tried the dehumanizing factory life. I worked in a department store for a month, and installed telephone central office equipment on Army bases. I finally decided that maybe I needed that degree after all… but having cut the cord I now had to go for it on my own.

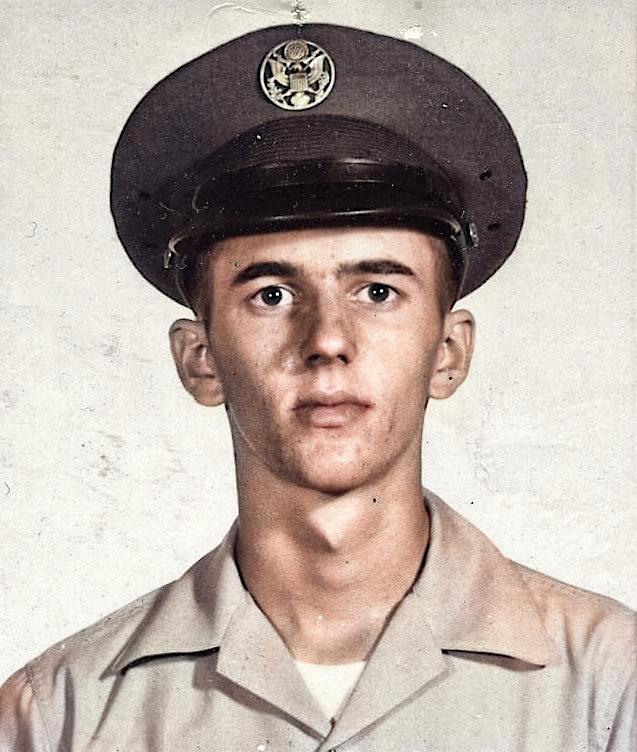

How else? I joined the Air Force during the Vietnam war.

It didn’t take long to discover that despite the idealistic picture painted by the recruiter, I was not to be in research, this was not to be a great adventure, and there would be no free education beyond specialized tech school. Charged with the task of swapping black boxes in F-111 jet fighters, I huddled on the frozen Idaho flightline in my parka and rankled… confined to an intellectual straitjacket and supervised even in the private world of my dorm room.

He was an 8-striper with power. I was a misfit, earning his respect and contempt with my confusing combination of technical knowledge and anti-war sentiments. When I heard rumors of extended inspection visits to my room filled with lab equipment and communication gear, I built an intervalometer camera system that would record, on film and tape, anything that went on for 15 minutes after my door opened. Evidence mounted quickly: he was going through my desk — commenting out loud that “one way or another I’m gonna get this sonofabitch court-martialed… damn, he’s even got his own die set.”

I made a splash that got him off my back, but satisfaction was short-lived. Pressure mounted from all sides — surprise inspections, harassment, disappearance of my cat, orders to get rid of my ham station and all the other “junk” in my room (I was designing an arbitrary signal synthesizer). Within 3 weeks I had orders to go to Guam in an unrelated career field, and I quickly understood that it was a death sentence. There were too many of ’em to fight. I saw my opening: we eventually agreed upon an honorable return to civilian life after a few months working in a precision measurement lab.

I hit RESET and tried again.

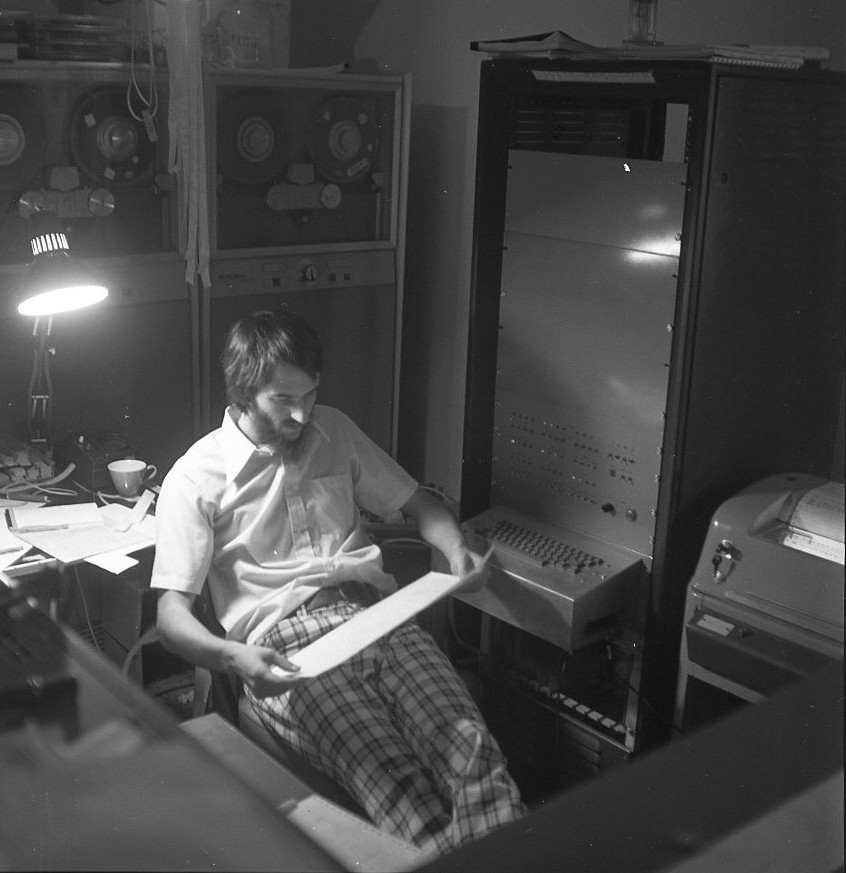

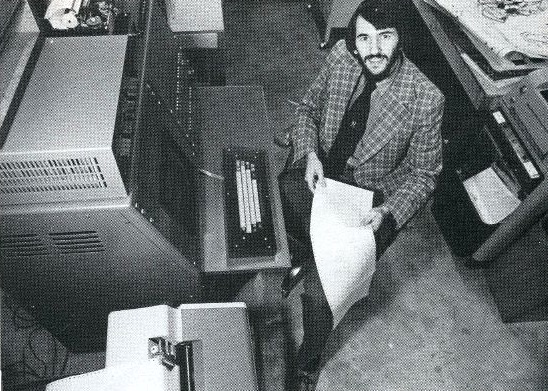

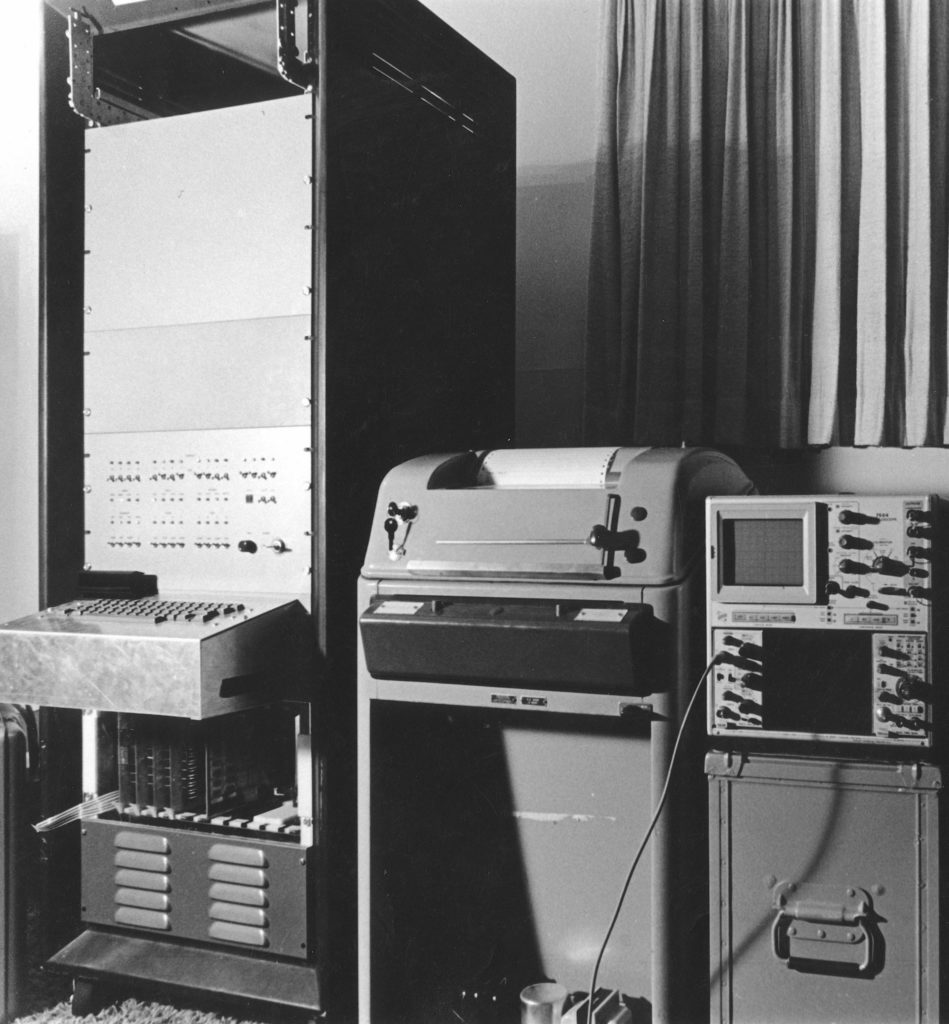

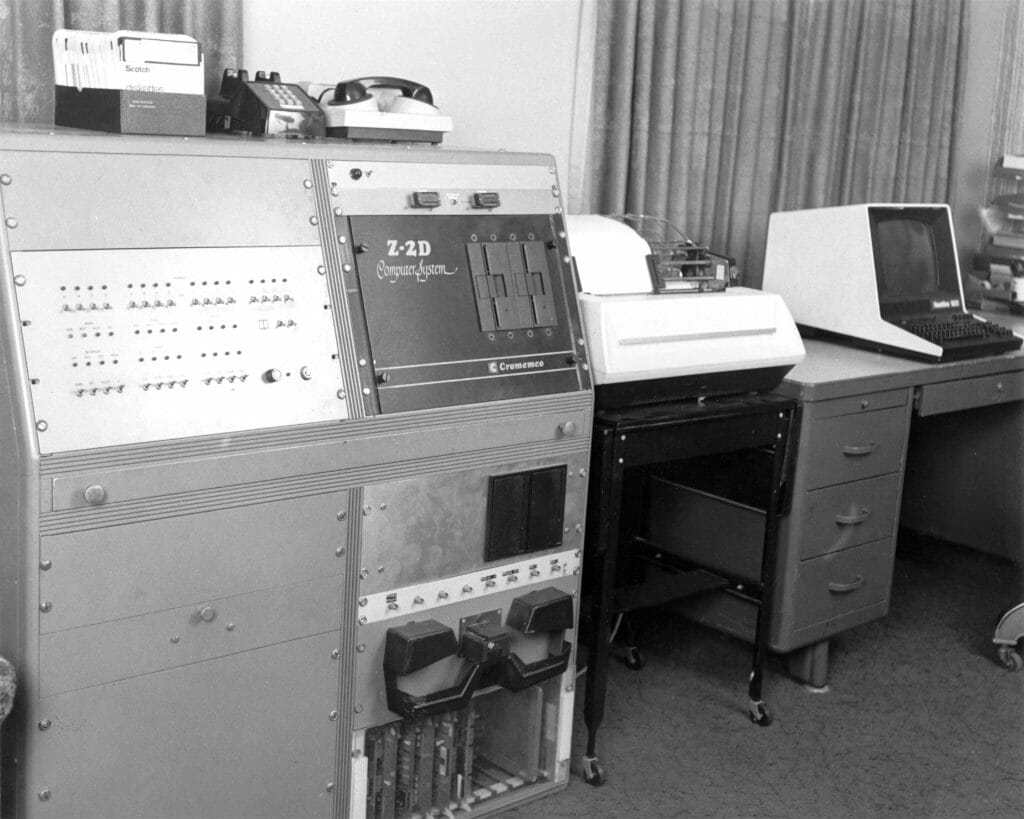

Field engineer, Singer Business Machines: a year’s education in how not to design computers. But now my real attention was much closer to home; in a Louisville apartment my techno-passions reached a new peak: by mid-1974 I had designed an 8008-based computer system jokingly named BEHEMOTH (for Badly Engineered Heap of Electrical, Mechanical, Optical, and Thermal Hardware), a historically significant early personal computer that is now on display in the Computer History Museum.

I started a moonlight parts business called Cybertronics to support my habit, hustling integrated circuits and related hardware, doling out plastic-bagged silicon goodies to the growing population of microprocessor junkies in those exciting early days of personal computers. What the machines lacked in capability they made up in class: card cages full of wirewrap boards, blinking front panels and massive power supplies, teletype machines, graphics with 8-bit DACs, hand-coded monitors and line editors…

Cybertronics became my full-time support. 1K x 1 bit static RAMs went down to $8.00 each, then to an unbelievable $3.50. The 8080 made a splash at $360 and I managed to find some I could sell for $250. The excitement was tangible; I devoured EDN and Electronics Magazine as most 22-year-olds would devour Penthouse — staying up all night when some project was too exciting to put down. Engineering schools could take a lesson from this: learning follows from passion as surely as pregnancy from fertilization.

And so was born an engineering firm. Word got out that some kid was designing with micros right there in Louisville, and within a few years I was building custom industrial control systems for Corning Glass, Seagrams Distilleries, Honeywell, and Robinson-Nugent — working out of a local industrial park and branching out… selling the new generation of IMSAI computer kits (What’s this world coming to? Any bozo can have a computer now…) and still pushing chips by mail order. All the signs bespoke imminent wealth, but something was terribly wrong.

My all-nighters, when they happened, no longer had much to do with passion. They had to do with fear — of deadlines, of customers, of disaster. One had to do with tracking the ravages of an embezzling secretary; another with an ultimatum from a client; yet another from an expensive lesson about partnership. My favorite toys were turning into business equipment, and this was getting to be way too much like work.

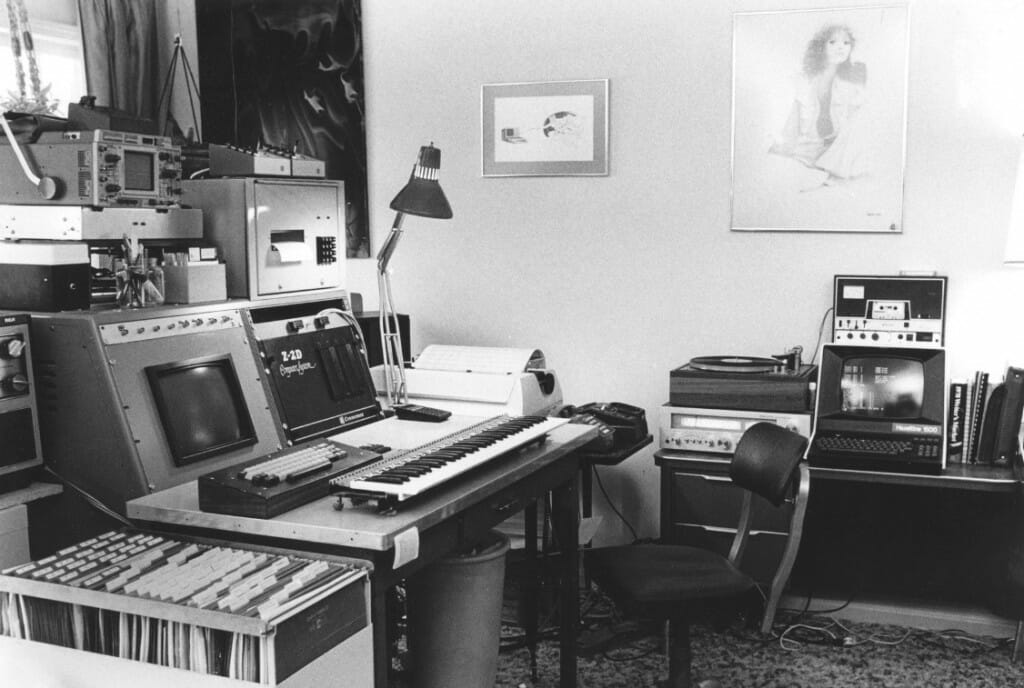

I cannibalized the company, escaped the industrial lease, and moved alone to a cavernous Victorian house where I continued tinkering, consulting, and writing magazine articles. A couple of years later, my girlfriend and I got pregnant, so we married and moved to Columbus in 1979 — where a software engineering job promised to fatten my bank account at last and buy me the space to do some real writing.

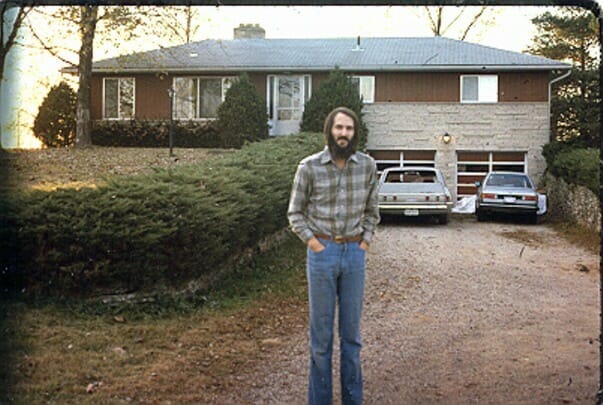

I signed a 30-year mortgage on a 3-bedroom ranch house in suburbia — an acre along the Scioto River. A beautiful girl-child was born. I commuted to work in a Honda station wagon. And in the cold, gray Ohio winter of 1980-81 I started to panic, recoiling from the routine that had settled around me. My old computers were cobweb-shrouded, lying idle, while I had been reduced to writing software for a living and arguing with my boss about design methods. Imprisoned, frightened of the scope of the next change yet even more frightened of not making it, I quit both job and marriage.

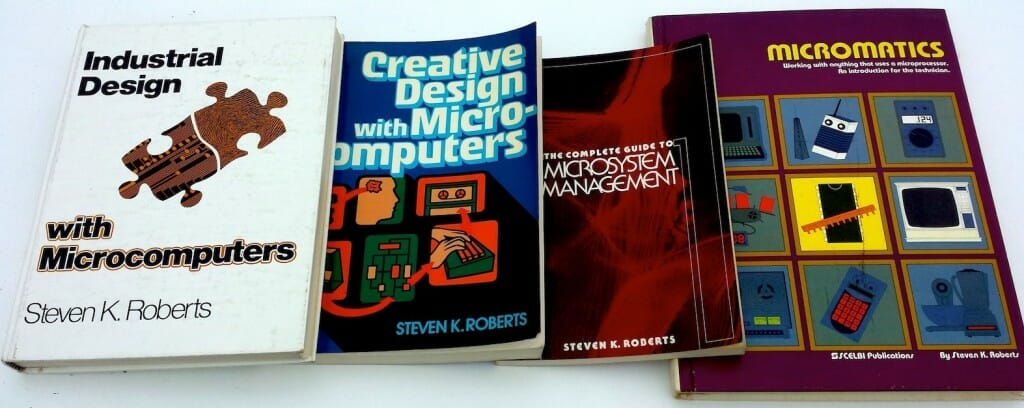

I dusted off the word processor and began. For three years I wrote a book a year and did tech-writing for local industry, filling in the gaps with articles about artificial intelligence, robotics, online information retrieval, emerging network communities, and microprocessors. My textbook, Industrial Design with Microcomputers (Prentice-Hall), was a complete distillation of the Cybertronics era, carrying the exuberant message that “art without engineering is dreaming; engineering without art is calculating.”

Freelance writing was a license to be a generalist and it had its moments, but still… something was amiss. I had turned another passion into a business. I was chained to my desk, working my ass off to pay for a house I didn’t like in a city I didn’t like, even though I looked successful.

What I really needed was a lifestyle that would combine all of my passions: computers, gizmology, ham radio, bicycling, romance, adventure, steep learning curves, the transcendence of the well-turned phrase, interesting people, the buzz of publicity, and most of all change — non-stop change — weaving through my life as naturally as breath. Hmmm… how do we pull off this caper?

The story begins in March of 1983, in that house on the outskirts of Columbus. But first, let’s leap a year and a half into the future for a quick preview of the stunning life-inversion that was about to occur:

Introduction: An Office in the Sky

Telluride, Colorado

September, 1984

It was a grueling three-hour commute to my Colorado office this morning.

I left Telluride with a yellow day pack strapped to my back, and climbed north into the mountains through the golden glow of early-October aspens. I followed a trail laid down over a century ago by miners who defied gravity, weather, reason, and each other in the quest for that alluring glitter in the very veins of the earth. They trudged these slopes lugging mining equipment; I carried a computer system, a towel, a bag of pretzels, and a Cannondale water bottle.

The trail wound higher and the air grew chilly, but I was warmed by the sun and the exertion of my 1,700-foot climb. I paused to take one last look down at the colorful town, then strode deeper into the mountains, further into the silence and smells of the forest, closer to the Colorado sky with every panting step. An exuberant brown dog emerged from the woods to join me, and we took a side trip to gasp at the view from a windy promontory and share a few pretzels.

But I couldn’t be late for work.

The dog and I clambered down a rocky slope and picked our way through the remains of the once-thriving Liberty Bell mining camp. All around lay the detritus of long-ago habitation: snow-crushed buildings, paper-thin remnants of tin cans, thick steel cables snarled and half-buried in the loamy earth. Obscure pieces of equipment deep in the arms of entropy were well on their way to oblivion, ancient mud around them stained reddish-brown with a century of rust. Boards crumbled under my step. My friend sniffed everywhere, then found a patch of snow in the deep shade of a wooded hillside and invited me to play.

But work beckoned — my business is serious. I stepped carefully through a mangled pile of corrugated steel roofing, avoiding the nails and razor-sharp edges, then swung my pack down onto a desk I built yesterday from a rusty miner’s bedframe, logs, and the remnants of fallen walls. My chair is an old dynamite crate; my computer a Hewlett-Packard Portable. I flipped open the display, fired up Microsoft WORD, and here I am at work — pattering into a mountainside text file while somebody’s affectionate dog utters happy muffled snores at my feet.

A deep wooded valley falls sharply away before me — the aspen in every shade of yellow from dazzling to gone, the pine a uniform deep green. There’s generally a randomness to their intermingling, but one entire hillside blazes in unbroken golden glory like a reunion of Big Bird’s descendants basking in the afternoon sun.

It’s not a bad office. Nice decor.

“Yeah, but you’re gonna get snowed in,” I was warned yesterday. “You’re gonna need a truck to get that crazy thing outta here.” The speaker gestured to my Winnebiko, an eight-foot-long machine bedecked with solar panels and enough state-of-the-art gizmology to start an engineering school. “Unless, of course, you can hang tire chains on that rear wheel there and stick some kinda ski up front.”

But I’ll take my chances — I rather like this town. The bike is locked to a friend’s porch, the security system set to page my pocket beeper if it detects tampering. My gear is piled against the living room wall, and I spend my days walking in the mountains, writing, and socializing via satellite with my electronic pals all across America.

(Tonight I’ll sign on to the computer network and transmit the Introduction to my editor.)

No, I’m not on vacation. I am a high-tech nomad — pedaling a recumbent bicycle around the United States with a portable computer while funding the journey with a sporadic outpouring of words. It’s a good life, for I have finally figured out how to get paid for playing.

So how did all this happen?

The tale begins not here — but a lifetime and seven thousand miles ago, way back in Ohio.

You must be logged in to post a comment.