The Outer Banks

Computing Across America, Chapter 13

by Steven K. Roberts

November 22, 1983

There is no such thing as a pretty good omelet.

— French proverb

Not surprisingly, the first harbingers of the Atlantic Ocean were not fish smells and sea birds, but billboards — acres of billboards. An hour out of Norfolk and they were already promising relaxation, fine dining, great fishing, and endless happiness in the resorts of North Carolina’s outer banks.

Behind me was Virginia, and I felt freshly steeped in a rich brew of American history that no canned textbook could ever hope to match. But that hadn’t fully sunk in: far more thrilling was the ocean — the ocean! — the first of my Really Major Objectives.

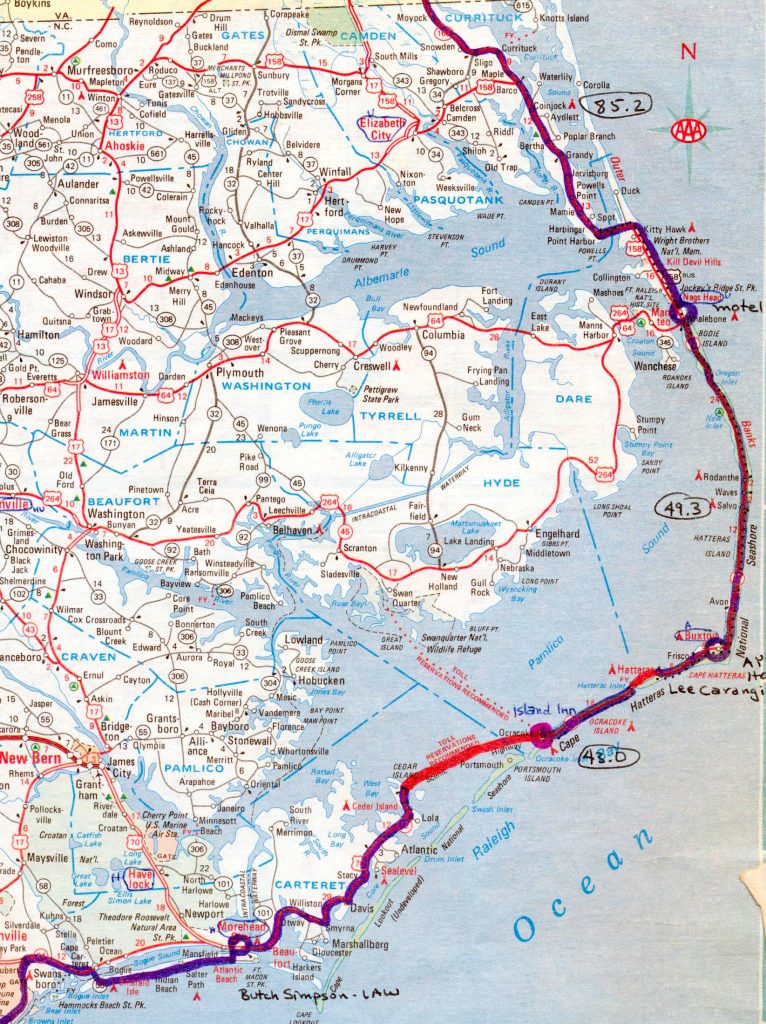

Yeah, I was now far from home (as if there was ever any doubt). Through Sligo and Currituck, Coinjock and Spot I pedaled, sniffing the air for the salty funk of low tide. Yeah… God damn. The Atlantic!

And there it was: the bridge across the sound, the welcome center, the unbroken hazy horizon of Big Water. I dismounted and staggered to the waves, feet slogging through damp sand, breath coming in puffs. An observer might have thought me a traveler returning home, so reverently did I taste the foam and gaze out to sea.

“Man, that’s a lot of water,” I was thinking. “And that’s only the top of it…”

I continued south past the sand dunes of Kitty Hawk, the Wright Brothers monument, and mile after mile of vacated condos. I was too far north to find an active November beach culture, so I pedaled along until well after dark — stopping at the Nag’s Head Mall hoping for a rerun of the events that had made Uniontown such a pleasure.

But the year-round community here is a small one. When the tourists leave, little remains, and a dozen or so people lazily wandered the quiet shops as snow flurries blew around the doors. I dined on a boring fast-food burrito (another packet of hot sauce, please) and tried unsuccessfully to find a place to stay. Within the hour I settled for a beachfront motel with off-season rates.

The room offered a fine view of ocean blackness, but the quiet was spooky: no kids, no TV from next door, no parking lot bustle of unloading baggage. There was only the ice machine to interfere with the rumble of the surf, and it sent clunks and whirrs through the walls to startle me as I gazed in self-congratulation at the atlas.

Restless, I assembled the flute and went out to walk the blustery beach. Ah yes, the ocean! Alone in the dark, intoxicated by the taste of salt air, I raised the instrument to my lips. Silvery strands of music began to frolic in the surf like minnows, darting and glittering through waves and foam, disappearing under dark water only to flash moments later in the moonlight. I walked slowly, drunkenly, playing all the Bach I knew — then suddenly cut loose with a free-form musical celebration that echoed wildly from the dark hotels. The wet basso profundo of the surf was the perfect accompanist in this impromptu duet for silver fish and bass.

There are two ways to play an instrument. You can perform a piece, like Bach’s Suite #2, constrained by the intentions of the composer to do it “right.” Or you can just relax and say whatever it is you feel like saying in the language of music — a statement less sophisticated but doubtless more sincere. After embarrassing myself by flubbing the Bach, I realized that the reason I had walked out there in the first place was not to perform but to express. There was something I needed to say, and words couldn’t quite do the job.

Imagine: I had uprooted myself, dismantled a stable existence, and pedaled fifteen hundred miles into an adventure of unknown implications. I now stood on the Atlantic shore with the power of the ocean roaring through me. Sitting in a motel tapping on the computer or scratching in my journal would have been a rather wimpy way to shout YAHOO! But music… without inhibition or thought for technique, I raised a triumphant cry of jazz? blues? impressionism? Whatever the idiom, it hit the spot, and when the chill of the night began to modulate my song with shivers I jogged back inside with a smile on my lips.

The exuberant beach music was a healthy prelude to the exertion that lay ahead. I set out refreshed under overcast morning light, immediately meeting a red-faced cyclist heading the other way. “Forget it, man, you’d be crazy to try it. That is one ass-kicking headwind out there. I decided to turn around and have a beer.”

I gave him a jaunty wave and pressed on. Within the hour, I was on the Pea Island National Wildlife Refuge, fighting brutal headwinds, peering into the endless unchanging distance for something, anything, to distract me from the relentless pain of this unexpected death march. Even the rare SOFT SHOULDER sign was occasion for a flicker of interest; even the occasional passing cars triggered waves of curiosity and speculation.

A flock of double-crested cormorants in Pamlico Sound sensed the oddness of my presence and took to the air in perfectly choreographed flight. Like a sinuous snake walking on water, they followed their leader, rising and falling in languid synchrony from twenty feet above the surface to a level so low that their wingtips brushed wind-driven ripples. At last they settled between a pair of sand bar islands, parallel necks jutting from waving thickets of marsh grass as they peered stern and one-eyed at my passage.

I stopped to stumble across short grass-tufted dunes and gaze at the gray surf, then discovered something strangely disturbing: my FM Walkman was silent. Dead. No country music, no bible-thumpers, no ads for Groll’s Furniture in Waldo, no distant rock ‘n roll. Nothing. I kept thumbing the dial like a man feeling for a lost wallet, but found only static. This was real desolation: a land owned not by developers but by skimmers, herons, cormorants, pelicans, gulls, and loons. As I stood in a whispering blend of static and surf, three pelicans cruised by, bound for who-knows-where, one of them veering off to crash beak-first into the ocean for a lunch of fresh fish.

Back on the road, I fought my way from one SOFT SHOULDER sign to the next — with visible short-term goals, there was a sense of progress. Passing them took a long time, and I thought wistfully back to the brisk tailwind of Route 5 between Richmond and Williamsburg, a force like a great silent engine that had propelled me for almost sixty miles. I even entertained the crazy notion of coasting back to Nag’s Head to join the red-faced chap in a six-pack of defeat.

But I pressed on. The passing cars offered no pleasure, their drivers dour and seldom returning my waves. A mediocre luncheon buffet place was no help — the waitress was too busy being charmed by a passing trucker to notice my needs. (“There was this traveling salesman,” the guy said, staring at her chest. “Have you heard it?”) I left a small tip and stepped out into rain, yet another obstacle tossed in my path to challenge the obsession behind this journey.

When I made the effort to look past discomfort, however, the land was rugged, wild, and actually quite a pleasure. A sort of Gandhian passivity develops when you’re miserable enough for long enough, and I found myself beginning to enjoy the cold, the struggle, the painful passage of every mile. I was riding a thin strand of land far out in the ocean, a fragile strip about three feet above sea level, an ephemeral piece of real estate that changes so much from year to year that most maps are obsolete. This was no time to complain.

Change is a way of life here. A graceful bridge that once arced over an inlet now crosses dry land. Wind, rain and surf pound everything from houses to the island itself, with the result that the local population has a rather unconventional notion of ownership. Cars turn to rust; shoes fall apart; houses rot, fall victim to carpenter ants, or disappear in hurricanes. A piece of land owned by the last generation is now a swamp, and the Environmental Protection Agency won’t let this generation touch it because it hosts a lovely crop of black-tipped spike grass.

Yes, Mother Nature always wins — sometimes with human help, sometimes in spite of it.

Pedaling in the rain yielded an unexpected treat: the freshly paved road out of Salvo was mirror-smooth from recent soaking. I rode in the October sky, looking down on heavy clouds surrounding a single patch of sunset orange, with nary a ripple of asphalt to suggest that I wasn’t floating in the air.

“Keep going,” I urged myself at the onset of dusk. “Thirty-three strokes between telephone poles — watch this truck — better turn on the blinker — damn, that lighthouse may be the tallest one in the country, but it sure ain’t gettin’ any closer — keep going, keep going…”

And finally I reached the Cape Hatteras Hostel.

Rubber-kneed, I pushed the bike down a puddly sand driveway beside a little harbor. Boats knocked against dark moorings; a dog barked a warning at my presence. The hostel — Lee Carangi’s basement — was equipped with the basic paraphernalia: bunks, central table, stove, makeshift shower. But that’s just the functional part: Lee is a dedicated hosteler and offers fishing trips and warm hospitality to visitors. The moment I felt his hearty handshake, I liked him — and quickly discovered that he is a long-distance cyclist as well. On one wall of the bunkroom there was a huge map of the eastern US with his Maine-to-Key West tour marked in red.

Lee’s trek had been a charity fund raiser, and he pedaled with a light load as his wife covered the mostly-inland route in their car. Key West’s WKWF radio gave him heavy promotion throughout the trip, offering a prize to the listener who could most nearly predict the date and time of his arrival. He traveled quickly, not stopping for exploration.

And I came to realize something as he spoke. But for two or three short layovers, I had not taken the time to relax and see since leaving Columbus. My journal was a sketchy thing of superficial road impressions; my new friendships were brief and undeveloped. What the hell was the hurry, anyway? Nobody was speculating on the date and time of my arrival — nor even the place, for that matter. There was no meaningful goal that had anything whatsoever to do with miles.

The red line in my atlas was the trophy, not the game.

Slow down and pay attention! I was beginning to understand this, but it would still take a while to fully sink in.

Lee made it to Key West on his trek, then immediately had everything stolen — bike, camping gear, camera, clothes, money, all of it. He finished telling the story of loss and depression, then leaned back, adjusted the sailor’s cap that somehow perfectly suited him, and raised a weathered finger of warning. “Be careful in Key West, Steve. The causeway from Miami is narrow and dangerous, and there are thieves all over the place.” I felt a twinge of fear — Key West was another one of my Major Objectives.

There were a lot of unknowns out there, weren’t there? I had survived the Appalachians, but I did it by sneaking quietly along the banks of the Potomac. Now I was to make a beeline for the madness of Miami, then fight my way across forty-two narrow bridges to the bicycle-thief-infested Cayo Hueso. Hmm…

On the road, back into cold wind, Winter on my ass, only the Hatteras ferry and my first palm tree to break the tedium. When I missed the four o’clock ferry to Cedar Island, I holed up for the night in Ocracoke’s Island Inn. Desperate for conversation in the off-season quiet, I shivered in the phone booth for over an hour before huddling under the covers to peer through a crack at the snowy black-and-white TV.

Ocracoke. It was not the rugged coastal charm of the place that lodged it permanently in my memory, nor was it the exceptional dinner of fresh flounder at the inn. It wasn’t the cranky heater, nor the smells and sounds of a fishing town; not the hibernating machinery of tourism nor the slowly dawning sense of south.

It was the omelet: raw oysters, wrapped in egg and served up with a lemon wedge. Ohio was suddenly far, far away.

You must be logged in to post a comment.