Thanksgiving

Computing Across America, Chapter 14

by Steven K. Roberts

Savannah, Georgia

November 26, 1983

Birth and death were easy. It was life that was hard.

— Tom Robbins, Jitterbug Perfume

Ashepoo, South Carolina — the day before Thanksgiving. I stopped to take a much-needed break from the two-lane truck route known as US 17, and parked the bike in front of a little roadside grocery. I pulled on a T-shirt clammy with the evaporation of morning sweat and started toward the door.

An ancient, yellow-eyed black man sat on a bench, watching me. I nodded in friendly greeting as I passed, but he stopped me with a deep, gravelly stream of barely comprehensible words. The sound was dark, mysterious, illiterate but somehow wise — echoing a culture I could never touch. He was as alien to me as was I to him, and we eyed each other with the guarded fascination that marks the first encounters between civilizations.

He jutted his chin toward a truck roaring past us on the narrow road. More words flowed, of which I could catch only “dat hahway ov’ deah.” He then nodded silently for a moment. I was about to speak, but he pointed a gnarled finger skyward and said something about “da mon upstaihr.” I gathered he was offering a benediction of safe passage, so I thanked him warmly and stepped inside to purchase a tasteless snack of low-grade, airy ice cream topped with a can of Hershey’s syrup.

And then I was back on dat hahway, approaching my tenth state as Thanksgiving day dawned gray, spitting, overcast, and blustery. In rainsuit and headphones I worked steadily into a headwind with the Savannah home of an old friend my objective: on this traditional family holiday I was feeling the loneliness of two thousand miles worth of motels and guest rooms. Many of the cars passing in the gloom were doubtless filled with people carrying pumpkin pies to dinner at grandma’s — an annual “pilgrimage” driven by the strength of family tradition.

Crossing the Broad River on highway 170, I hit a mist-shrouded bridge as lightning backlit the heavy clouds — with the Savannah public radio station choosing that precise moment to begin playing Richard Strauss’ music from Macbeth. There I was, somewhere in South Carolina, pedaling toward a dark storm as birds shivered in the marshes around me and dramatic music filled my head. Despite the elements, I grinned; despite the exhaustion I took ‘er up a gear and pushed hard for Georgia.

The storm neared. All around me was wild, open marsh with nothing to slow the raging wind. It came now from starboard, whipping at the Baggies rubber-banded over my instruments and the plastic shower cap covering the electronics package. Cars roared by in an opaque spray; the music, incredibly, now Handel’s Water Music. And then I hit the Savannah River bridge — one of those high graceful bridges that can pass tall ships without interrupting auto traffic.

I climbed slowly as the rain grew serious — big fat drops, whacking hard from the side. I leaned into the wind and kept plodding, looking out over dark shipping ports and the socked-in city as I slowly rose into the black clouds. Without warning, the bike started skidding out from under me.

Whoa!

Traction had disappeared. The whole summit of this mighty structure was one of those steel gratings, the kind that sings beneath passing cars. I could see through it to the gray river far below, but I had no time for that — the wind was so powerful that I crabbed across the slippery surface, sliding sideways while pushing forward, feeling more like an airplane than a bicycle. Cars passed with headlights on, their cozy occupants staring incredulously as I pedaled through the Georgia sky and fought to stay vertical.

The rain grew still heavier as I hit the down slope and accelerated toward Savannah. 15, 20, 30, 40…. the rain stung my face hard, almost blinding me, soaking through already-wet clothing. There is a fine line between serious discomfort and the insane bliss of intense sensation, and I crossed it at 41 miles per hour — changing lanes in heavy traffic to pass a Michigan camper with its brake lights aglow, lumbering timidly down the hill. The passengers must have thought me loony — laughing wildly past them on a flashing blue lawn chair in the heavy November rain.

Within the hour, I had rolled through graceful tree-lined streets and found my way to Wilmington Island and the suburban home of Tom Rouse. He and I had become friends years before in Louisville during a time of entrepreneurial fervor — a time of custom engineering and microcomputer design. That was the era of Cybertronics; Tom had been my business manager, working for next to nothing to help keep my fledgling company afloat. It was he who dealt with the IRS; it was he who accompanied me to the bank and helped seduce no-nonsense loan officers into believing that the business had a future.

It didn’t, of course, but that was my fault, not Tom’s. I just grew tired of the stress and began to see writing, not computer design, as the career of choice. I took off to get in the pants of the media; Tom moved to Savannah, where he became controller and resident data-processing wizard for a large grocery-store chain.

I arrived early — and they were off having turkey dinner with parents on Hilton Head Island. I let myself into the garage, changed into dry clothes, and conjured a Thanksgiving feast on their ping-pong table of chicken glopola, GORP, and coffee. Feeling just a little sorry for myself, I dusted off a lawn chair, crawled into my sleeping bag, and fell asleep beside the lawnmower.

But headlights and slapping wipers woke me, and before long we were cozily chatting in the living room. It was a good feeling, a close one: my old friends Tom and Bunny, the kids Tina and Tony, basketball on TV. Beer, chips, and the swapping of tales. A clean body, and laundry churning in a New Improved surfactant stew. The show ‘n tell of my journey. Sitting in the warm holiday nest of this nuclear family, I suddenly thought of my own family — and the strange twist that had recently come into it. “Tom,” I said, “I made an interesting discovery since we last talked.”

“Yeah? What’s that?”

“Well, you knew I was adopted, right?”

“I remember your saying something about that. It happened when you were a baby, didn’t it?”

“Yes, I was three months old when the deal closed. Well, curiosity finally got the better of me. A couple of years ago I started searching for my biological parents, and finally managed to track ’em down.”

“Wow! That must have been an experience. Have you met them in person?”

“Sure have — as well as some of my newfound siblings. It’s a bit of a shock after being raised an only child: I suddenly have seven brothers and sisters, four parents, a new grandmother, and various aunts, uncles, and cousins. That’s one of my projects on this bicycle trip — there are a lot of new relatives out there to meet. A whole passel of ’em are down the road in Gainesville.”

Bunny spoke up. “But how did you find them? Did you have to get a court order?”

“Oh, not at all. I had a few clues to start with — my mother had the foresight to make some furtive notes when she and my dad adopted me.” I briefly outlined the contents of that document, then went on to tell my friends the story…

It took about three months of casual research, guesswork, and cross-correlation to find them. I browsed old telephone directories and called the adoption agency, the hospital, and even the judge who had handled the case. I snooped and sleuthed, probed and pondered. Before long, I received my pre-adoptive birth certificate from the state of Pennsylvania and found my original name — and that of my biological mother.

After that, things moved quickly. Within two weeks, I had my bio-mom’s address and phone number. Too impatient to use discretion, I picked up the phone and called her.

“Sylvia? This is Steve Roberts.”

Naturally, she had no idea who Steve Roberts was, so she just said, “Yes?”

“Tell me, Sylvia: What were you doing on the evening of September 25, 1952 — at about 6:35 p.m.?” I trembled as I spoke.

There was a long silence on the line; for a few seconds I heard only static. Then, in a quavering voice, she answered, “I was having a baby.”

“Ah! Well, I’ve changed a lot since you last saw me, Mom. I’m a lot taller now, and I have a beard.” I was almost afraid to breathe — I couldn’t believe I had just said that.

I waited, almost faint, for a sound. Say something!

The distant voice broke in a barely audible whimper. I tried hard to picture her: a woman in her early fifties, puttering around her northwest-Pennsylvania home on a routine weekday afternoon, the child of her youth far from her thoughts as she ran for the phone. Now I could hear her trying to mouth the words, choking on every attempt. Twenty-eight years had passed since she handed my tiny body over to strangers.

It took a while, but she finally spoke. “Hi, honey,” she said. “I missed you.”

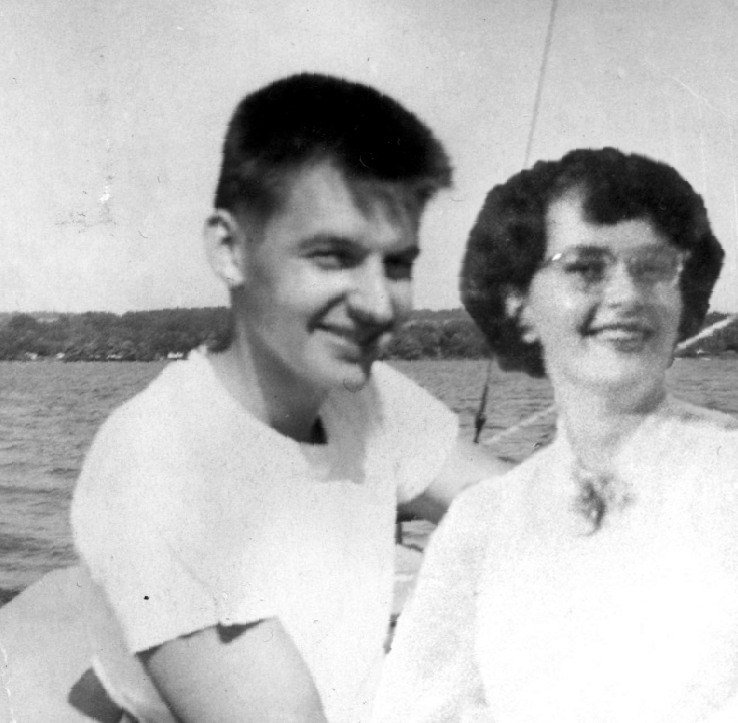

We had quite a conversation. I discovered that I was the unexpected product of a tasty New Year’s Eve tryst between a jeweler and his twenty-two-year-old sweetie. But the year 1952 was not the ideal social climate for a “bastard child,” so when I innocently appeared in utero as the result of their carefree exuberance it was Big Trouble for all concerned. (Sylvia’s address at the time of my birth was the Florence Crittenton home for unwed mothers.)

She told me about the big cover-up — the neighbors convinced she had gone off quite properly to a private school.

I hung up the phone with a new sense of personal history — and the name of my bio-dad. The last Sylvia had heard (1954), he was a jeweler in Rochester. This one didn’t take long. Within less than an hour, I had followed his illustrious tracks to an island off the coast of Maine, where he has become a well-known sculptor. The final clue came from the curator of the Renwick gallery in the Smithsonian.

“Hi, Ron,” I said on the phone. “This is Steve Roberts. What were you doing on the evening of December 31, 1951?”

I couldn’t resist.

Ron’s career has been one of art and expression, and his father had been even more like me: turning away from a promising future in aircraft design to seek his fortune in the arts. My bio-granddad lived a life eerily parallel with mine, not only publishing seven art books but making his own long-distance odyssey while writing articles and receiving heavy news coverage. His had been a 1909 circumnavigation of the eastern US in a homemade boat.

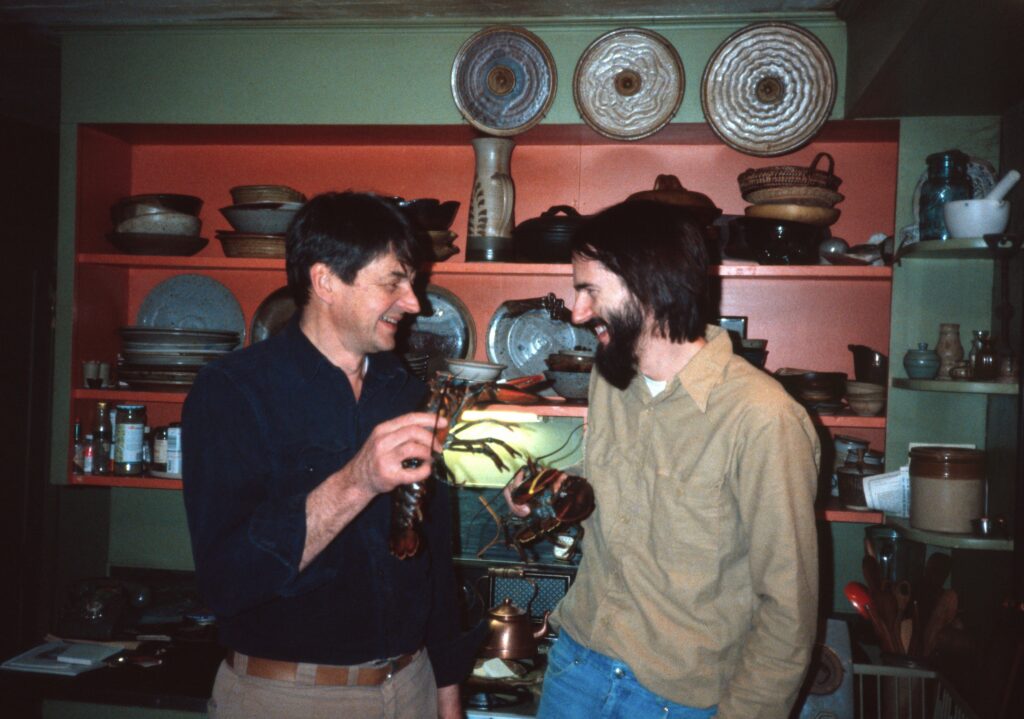

In the months that followed those phone calls, deep friendships grew in this link between families. I flew to Maine to meet Ron, liking him immediately and discovering the genetic origin of my characteristic nose and lanky frame. “This is the way to have a son, isn’t it?” he said with a twinkle, introducing me around his studio. “He comes into your life at age twenty-eight — no diapers, no adolescent crisis…”

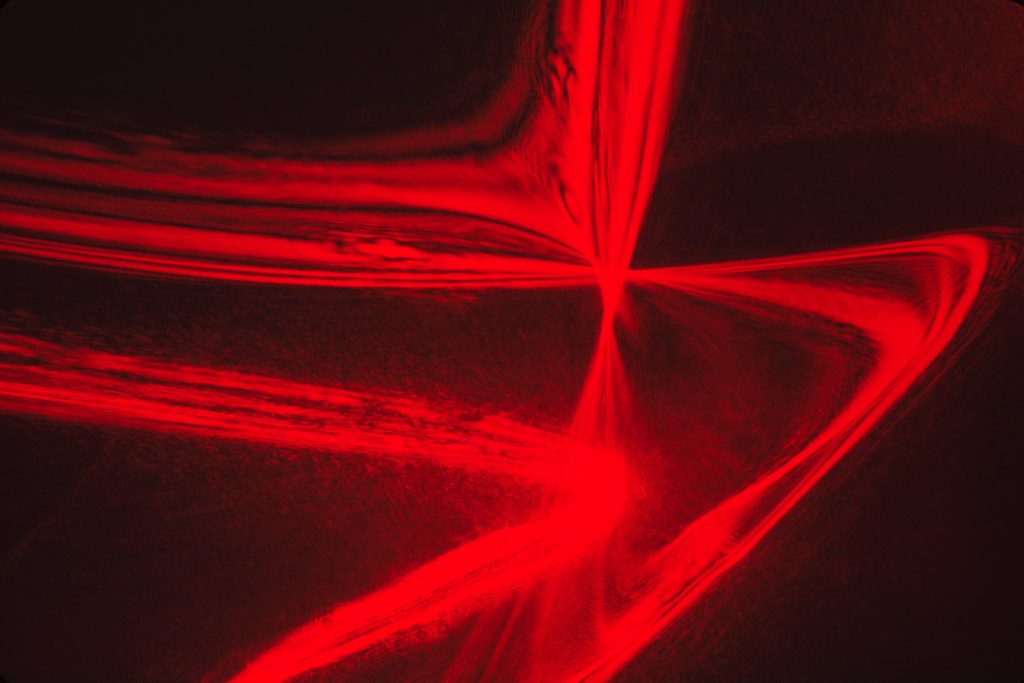

Sylvia visited me in Columbus a few weeks later. We spent the afternoon swapping tales and photos, and then darkness fell. I decided to present a laser light show for her pleasure.

I set up my helium-neon laser and the tripod-mounted piece of pressed glassware — an optical combination that yields a compelling visual ballet of diffraction patterns when operated with appropriate finesse. The choice of music was critical, so I selected Ravel’s delicious Pavane Pour Une Enfante Defunte.

I switched off the lights and began. The walls and ceiling of my living room came alive with red magic, the flaws of the glass converted into complex images that flowed from one to the next with the fluid continuity of Dance. It was a sight that never failed to transfix visitors, and it had become such a standard part of my social repertoire that I turned to Sylvia beside me on the couch and joked, “I always laser on the first date.”

But she wasn’t watching. Her face was contorting into a pitched battle between emotional breakdown and forced composure; her body was shaking with suppressed sobs. By the end of the first statement in this poignant impressionistic melody, she could take it no longer and fell against me with a cry of anguish.

I felt helpless, suddenly realizing that I looked a lot like my bio-dad during that fleeting romantic highlight of her life. I put my arm gently around her shoulder. “Sylvia? Shall we lighten up a little here? Do you want me to turn on the lights? Should I change the music? Are you OK?”

She turned to me and shook her head. “No, no, I’m fine. I just don’t know how you knew to choose this piece of music, that’s all.”

“Well, it’s been going through my head all day… really, I can change it — “

“Steve. I’ve played this every year on your birthday for the last twenty-eight years… while burning a candle. It’s the Pavane for a Dead Child.” She looked at me, her tears sparkling in the pure red light. Covered with goose bumps, I held her and felt the biological connection, a mysterious link new to me. And while Phyllis and Ed were fully secure in their position as my parents, I was opening a new and different place in my heart for Sylvia and Ron.

From them had come the spark.

The whole experience confirmed a long-held belief: my life is a blend of hereditary intuition and environmental reason. I was raised in a world of logic and engineering, developing an early passion for technology, tools, and quality workmanship… coached at the workbench from early childhood by my dad. Engineering school was a natural choice for one with such interests, but it didn’t take me long to make the depressing discovery that it was like going to an art school and learning to paint by numbers — I wanted tools, not habits.

Only a week before the initial contact with my bio-parents, in fact, I had written a line in my textbook that summed it up neatly: “Art without engineering is dreaming; engineering without art is calculating.” It was intriguing to see this so sharply reflected in the four parents, and although one example hardly allows sweeping conclusions about heredity and environment, it’s convincing enough for me.

“Well,” said Tom after I finished telling the story, “it sounds like you’ve found quite a set of roots.”

Bunny had been watching and listening in fascination. “Steve… happy Thanksgiving.”

I smiled at the two of them, appreciating their friendship and the link to the past. Thankful? Why, hell yes! I was living a dream, wasn’t I? For that matter, I thought with a sudden chill, I was living. I had shared an abortion once, and I felt a wave of deep gratitude to Sylvia for not making the same painful choice.

Thankful? Yeah. Very. This was probably the first Thanksgiving on which I took the time to think about how much there is to be thankful for — to friends, circumstances, and whatever deities populate our private universes.

“By the way,” I said, “there’s a nice little twist that adds a touch of mystical spice to this journey. Did you ever read that book called A Walk Across America by Peter Jenkins?”

“The guy whose dog died? Yeah, I’ve heard of it.”

“I just discovered something interesting last week: the house where Peter lived in Alfred, New York, before starting out on his walk was the house in which I was conceived 32 years ago.”

Who knows? Maybe some of those deities in our private universes get together now and then for a bit of fun.

NOTE: The story of my reconnection with my bio-mom is told in more detail as chapter 7 in this book.

You must be logged in to post a comment.