Life in the Desert

Computing Across America, chapter 46

by Steven K. Roberts

Palm Desert, California

December 31, 1984

Visits always give pleasure — if not the arrival, the departure

Portuguese proverb

It’s odd to be in a place where everything looks familiar, even though you’ve never been there before. At first, from the north, Las Vegas was just military/seedy, a sort of urban third world, the kind of place I usually try to avoid. But then the little incidents of deja vu began to occur… the buildings, the streets, the Hitching Post Wedding Chapel — Christ, even the people.

Perplexing. Sometimes my brain does that to me, when the synaptic thresholds are abnormally low. The system goes into a pattern-recognition frenzy: every face matches a friend, every gravel parking lot contains countless images embedded in accidental mosaic. Voices are familiar, even those plucked from the white noise of windblown leaves. This seemed to be happening in Vegas, an experience both welcoming and frightening.

I pushed further into the city, taking a detour down Fremont to gawk and be gawked at. At last I cruised The Strip and realized that this wasn’t a brain dance at all; it was a lifetime of detective-movie sets, countless tales of gambling exploits, and a melange of Hunter S. Thompson images — all rushing forward at once, elbowing each other aside in the attempt to occupy the strange reality around me.

Of course.

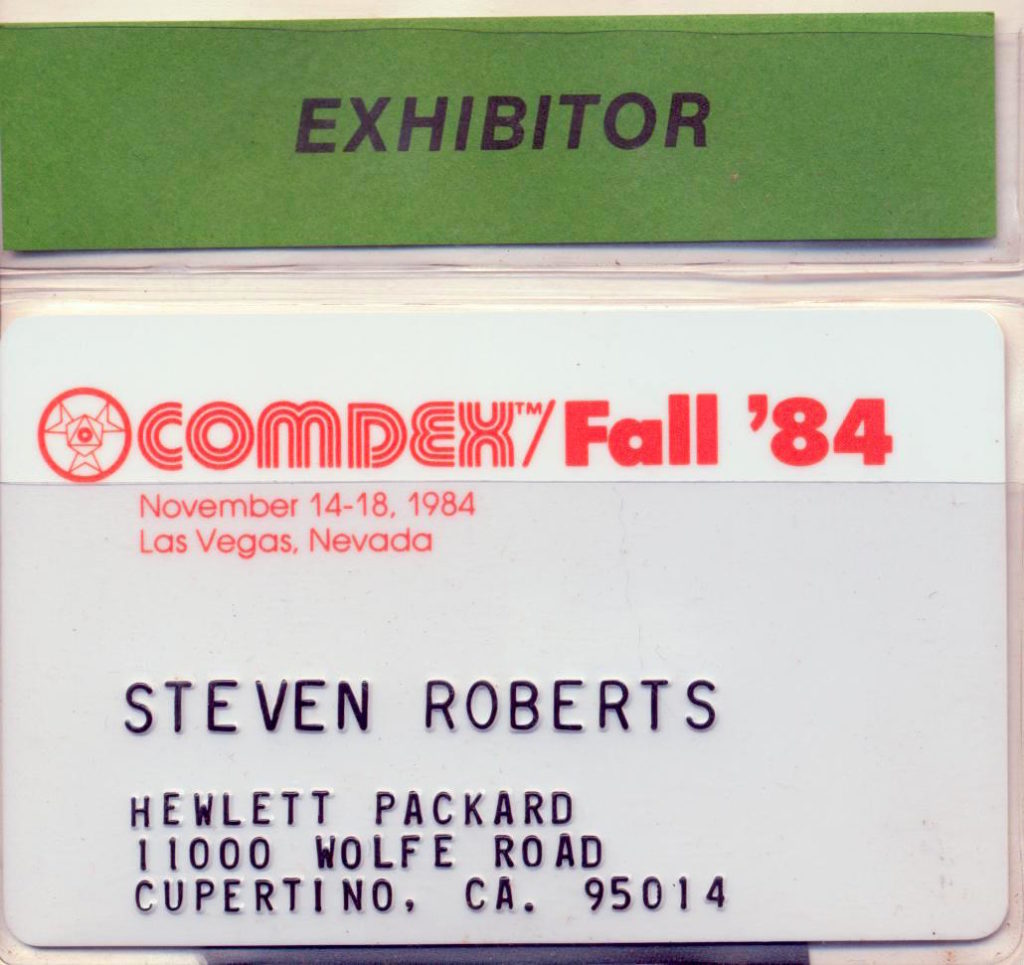

I found the Convention Center and put myself in a bovine frame of mind long enough to be processed through COMDEX registration. There were a hundred thousand people here to walk the thirteen miles of exhibit frontage — if you lined up everybody cozy in the aisles, there would be a person every eight inches, a sweating gray-suited queue of sore-footed computer people. A single nuke on Paradise that week would have given Japan an instant three-year trade advantage.

I wandered ground zero in my cycling garb, wearing a combination Exhibitor/Press badge. Heh. Attendees looked through me at first, then reacted with the startle reflex upon noticing my professional affiliations. It was a pleasant iconoclasm.

The old electricity was there, a “show excitement” that has infected me since childhood science-fair days, but my life was changing; I was technologically jaded. I looked more at faces than computer screens, more at bodies than boxes. Not so very long ago, I would have lugged around twenty pounds of brochures and methodically checked off exhibitors in the show guide until my blistered feet forced a halt.

That has changed, but I must confess that I did whoop with delight when Hewlett-Packard’s Bill Crow deftly struck a few keys on my Portable and generated a scaled sine plot on the screen. “Hey, I didn’t know it could do that!” I cried, remembering a time a decade before when a professional flutist had picked up my new instrument and sweetly sung Syrinx. I had gazed at the silver tube with a new appreciation, realizing that all sorts of potential magic lay within.

It was because of H-P that I was there. That long-ago phone call from the Llano, Texas, Dairy Queen had yielded not only an exquisite traveling computer system but also a powerful symbiosis of support and media exposure. I rode to COMDEX every day from the Alexis Park Resort Hotel, wrestled my bike onto a sort of floodlit tokonoma surrounded by potted plants and posters, did a few interviews, and then wandered the show looking for familiar faces. There weren’t many. Computer shows are now dominated by smooth marketing-types, not the brilliant weirdos and visionary tinkerers who once gathered wild-eyed to share dreams.

A big party was to happen one night atop the mighty Hilton — a catered, open-bar event for clients and friends of Hewlett-Packard’s public-relations firm. This would be a night breezy with the exchange of business cards, a night vibrating with the portentious handshakes of alcohol-lubricated deals a-making. Members of the Press would scurry about, reading name badges and eavesdropping for hints of unannounced products or corporate acquisitions. I was to be there as an invited guest, but… Red alert! All my T-shirts were dirty.

I sent them out in the morning, marked RUSH, via the hotel’s valet service. It would cost $13.50 to launder seven T-shirts and a pair of nylon shorts, but hey, this is the Big Time.

Evening. Still no shirts. This was the largest show of any type in Las Vegas history, and the unprecedented influx of three-piece uniforms had overloaded the laundry services. I fretted, fumed, and kept calling Charlie the bellhop.

“Man, I’ve got to be there in less than an hour! I’m a guest of honor.”

“Well, Mr. Roberts, our valet service is swamped by—”

“I know, I know! But when? You guys have all my clothes except for one sweaty Key West T-shirt and a Gore-tex rainsuit.”

“Well, uh, I’m six-foot-three and 165 pounds.” He paused for a moment. “How about you?”

I was thrown off balance. “Uh, six-four and 175.”

I have an Izod shirt you can borrow…”

So I found my way to the employee parking lot and changed shirts with the bellhop while my cab stood waiting. What is the customary tip for that?

And yes, naturally I had to try my hand at gambling. Feeling like a heavy hitter with my ten-dollar roll of quarters, I fed the hungry slots, a quarter here, a quarter there, fascinated by the allure. The casinos are plush, carpeted, and dazzling with lights and jackpot bells. They are places of beautiful waitresses with names like Capri, serious people in smoky gambling pits, change booths built like banks, furtive conventioneers keeping a wary eye out for co-workers, and old women with hundreds of dollars in quarters rattling around in their tupperware bowls and payoff bins.

I settled in to risk it all, picking a “Progressive Jackpot” machine that seemed to smile at me. I realize in retrospect that it was a sneer, a siren’s sly promise. There are microprocessors in these one-armed bandits now, you know, judging your psychology by the vigor of your “pull” and shifting the odds according to your eagerness. Knowing this, I had the advantage. I affected timidity, hoping to trick her into teasing me with a few payoffs.

She did. Yeah. I fell into the trap — thinking I had it figured out. I asked the white-haired lady beside me to hold “my” machine and ran for another roll of quarters.

It was time to get serious.

So that’s where they get the money for these fancy hotels.

Near the end, growing broke and discouraged, I plunked in a fifty-cent bet and got a triple-bar. My neighbor cried out in anguish, the shoebox of quarters on her lap clinking heavily as she scolded me without missing a betting beat:

“Oh, honey, don’t you ever run one of these with only two coins. Always use three! Oh my God, look what you’ve done! That’s a triple-bar — you could have had a hundred-coin payoff if you had just put in three quarters… That’s twenty-five dollars! Oh, that makes me sick, just sick. What a terrible waste.” She cluck-clucked and shook her head while continuing to feed the two machines before her, pulling the handles left, right, left, right as if milking an intermittent cow.

One last obstacle — the Mojave Desert. Without really admitting it, I had begun to look upon reaching California as something of a mission. There it was, only thirty-five miles away: a hundred million acres of lush greenery and nude beaches and beautiful women, a place where Perrier bubbles from underground springs, where executives take cocaine breaks, where all trends start and all wanderers stop.

I braced myself for the cadre of tan California Girls on recumbents, long blonde hair still wet from their latest sexual encounters in redwood hot tubs. All across the country, I had felt the mystique and the growing sense of expectation, and now it was just down the road.

“Hey, there goes one o’ them California bikes!” a guy in Texas had cried four months earlier.

“You from California?” people had asked all over. I had even met a guy from the Bay Area who seemed offended that someone on such a high-tech conveyance had originated in Ohio. The very nerve!

Of course, California is not so much a place as a four-syllable symbol of all that’s different, hip, high-tech, new-age, sexy, and weird in this country. This mystique is a necessary part of American culture — a label for the beginning of any trend. I knew this, but figured there had to be some good reasons for it.

So I checked out of the Alexis Park Hotel, calling the management’s attention to an erroneous $1,757 room-service charge. (It had been a pretty good omelette and Hewlett-Packard was paying the bill, but still…) I slipped a couple of mini-booze bottles into my packs and thanked the bellhop again for his shirt.

And with a local cyclist named Lamont, I pedaled off to the promised land.

Perhaps I should have recognized it as the harbinger that it was and turned around to spend the winter in Arizona. Starting my California visit with a high-speed wreck was not at all what I had in mind.

The groundwork was laid at a mountaintop gas station in the vast, boring Mojave Desert, where I stopped at dusk to seek a place to sleep. Lamont had turned back at the border and I was exhausted, interested only in the nearest motel. The locals peered curiously at the bike and said little; passing tourists gawked and moved on. There were no suggestions. I was about to set out on back roads for a bit of outlaw camping when a small sedan squealed into the parking lot and chirped to a stop. Two guys fairly leapt from the car.

“We’re groupies!” they cried in unison. “Computing Across America, right? Weren’t you just at COMDEX?”

“Yes—”

“Alright! You need a place to stay?”

“Well, as a matter of fact—”

“Great! We’ll get you a room in Baker. See you on the freeway!” Hardly waiting for a reply, they hopped back into their car and sped off into the night.

Phew. OK. Why not? Baker was only twenty-five or thirty miles away, so with a click of my helmet buckle I ramped back onto 1-15 and continued southwest. The fellows were friendly, and obviously into computers. Should be an interesting evening.

An hour later I was coasting down into a vast valley, the lights of Baker twinkling through clear desert air at the end of a ten-mile red/white line of vehicles. The roadside was littered with cast-off auto parts, and I took advantage of every passing pair of headlights to scan the shoulder for mufflers, oil filters, glass, tires, and other debris.

Suddenly I heard a smooth downshift and my friends were beside me, matching my 31-mph speed. “Hey!” one of them cried above the stereo, “We’re all set!” He fluttered a motel key in the wind and offered me a Coke.

“Nah, we’re almost there,” I hollered, glancing ahead at the distant town. “Let’s have dinner in Baker.”

“Yeah, they even have a restaurant called the Bun Boy!” They laughed, teeth flashing white in the night. There was a moment of pure delight, the shared laughter of a strange encounter in a strange place. I remember their dashboard lights, the tiny orange coal of a joint, the music, the wind, and a semi going the other way. Time was suspended.

And then a shredded truck tire materialized from the darkness a few feet in front of me, and I swerved to the right — too far. The pavement gave way to cactus, glass, and gravel.

There was no way to stay up… I veered further into the desert to keep myself from pitching back onto the pavement, and tried to take it down slowly in a controlled slide. But I was going much too fast for such heroics. My foot snared a cactus and threw me into a spin, and without really understanding how it all happened I ended up lying on the ground with a bloody arm and one leg twisted under the bike.

My friends skidded to a stop and were at my side in a flash, helping me to my feet, effusively apologetic and almost in tears. “No, no,” I said, “I’m OK — really, it was my fault, I wasn’t watching the road.”

“No, we were distracting you; we had no right to do that. Oh, I feel just awful… have you ever wrecked before?”

“Well, not really — a little spill in Cincinnati…”

“So you ride all the way to California and that’s the first thing that happens. And we’re the ones who did it to you! Oh God, I feel terrible, terrible. Are you OK?”

I looked at my arm and saw only shallow scratches. “I’m OK, but I don’t know about the bike.” I wrestled it to a standing position, noting the thrown chain, bent steering linkage, broken fairing, and the rattle of my coffee mug shattered in the kitchen pack. But it was all fixable, and with shaking legs I climbed back on and continued to a loony night in Baker.

Welcome to California.

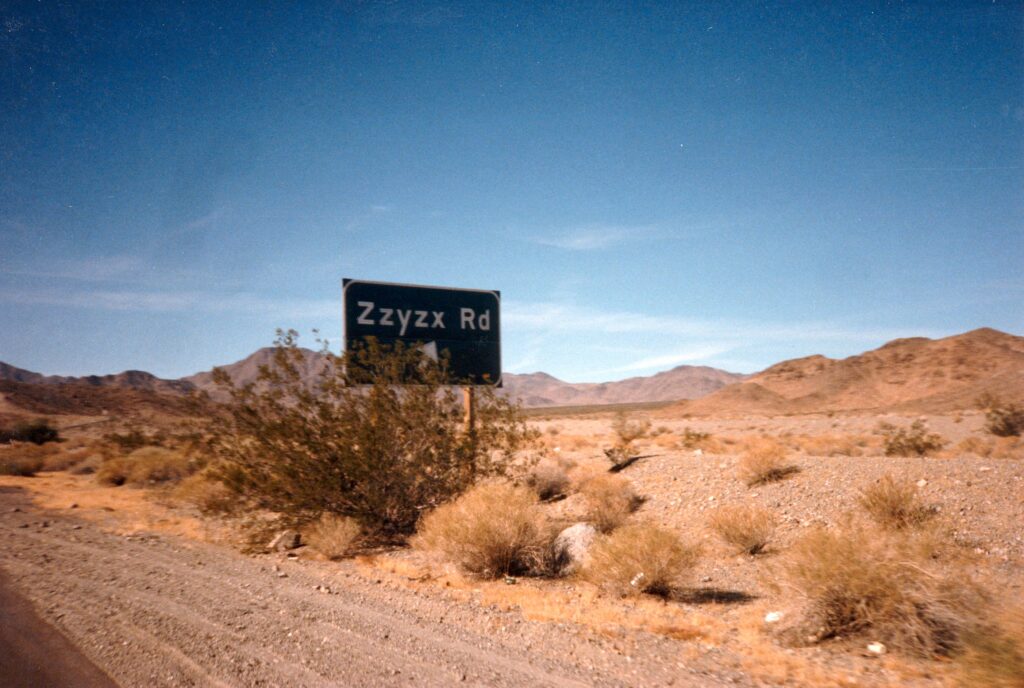

It didn’t take me long to tire of the desert. Two days after the accident I was still in it, bored, no longer smiling at the memory of Zzyzx Road or the crudely lettered SNAKE CHARMER 100 YDS sign south of Barstow. I was sick of the music on my twelve cassettes, and found myself deeply annoyed at riding east from Lucerne Valley to Yucca Valley. There were no direct routes from Las Vegas to Palm Desert.

Palm Desert? Palm Desert! Do you know how many times people have asked me why on earth I stopped in a colorless suburb of Palm Springs for five weeks? In retrospect, it seems insane, but I rode to the Land o’ Golf as if it were the mecca of passion, for there, amidst the artificial plants and expensively watered fairways, I would find a nine-year romantic fantasy. What but love could make me ignore the ocean, something equally close?

But the desert was driving me crazy. Buffeting headwinds, brutal hills, sagebrush, narrow roads, uncaring drivers, and boring, boring land. Interminable. Sand, sage, cactus, brown grass, routine mountains, dry lakes, dust, endless road, mile after identical goddamn mile.

I did manage to be astounded by one thing: people actually live out there. Little communities abound, not on the map, marked by clusters of cute name signs at the beginnings of dusty roads. The houses are spartan, the yards cluttered; here and there may even be seen the occasional brave attempt to farm a patch of meager ground. A grim life. I saw a few FOR SALE signs: one pink house on two acres was going for $24,000.

And then the journey grew fuzzy, stumbling to a temporary halt with a sudden loss of purpose. My original plan was simple enough: I would visit my old lover for a week of bliss, then continue to San Diego to rent an apartment and work on the book. I would then hit the road in the spring to begin the inevitable Computing Back Across America sequel.

But my life is not a tour bus subject to plans and schedules; it’s a hunk of errant tumbleweed that seldom even has the sense to roll downwind.

There it was: Palm Springs, an artificially green oasis in a naturally brown valley. Remi was down there somewhere… I coasted almost to sea level expecting the lawn sprinklers to squirt holy water. This had been one of the trip’s unspoken Major Objectives for over a year.

Money dripped from low buildings. I rode through opulence — past classy dress shops, rich hotels, country clubs, green lawns, and expensive cars. The profusion of sprinklers shocked me, and I remembered reading that nearly sixty percent of the fresh water used in California is sprayed onto grass. “Someday,” I thought with a sad smile, “all this will be brown.”

And suddenly there she was. We met with the exuberance of old friends long separated.

I moved in.

And within days, a perfect nine-year fantasy died. It didn’t just fade away, as most fantasies do; it struggled and screamed, lost consciousness, returned to life with wild intensity, went through stages of delirium and confusion, and finally kicked the bucket only to be replaced by anger and frustration. Ah, expectations. I think this time I learned the lesson.

Of course, I should have gone running back to the Other Woman at the first sign of trouble, but it wasn’t that simple. Remi and I needed and resented each other, loved and hated each other. Her insights helped shape the early chapters of this book; mine helped her start her own. So I remained in this mad setting, withdrawing more and more into writing and networking, trying to ignore the grim present in favor of my journey’s past and society’s electronic future.

Palm Desert is a strange place of two mutually exclusive social worlds. I fit neither. The first is the retired or transient rich — the golfers, the expatriates of everywhere who came for the weather and isolation. The second is the service sector that supports the first, a diverse crowd keenly aware of its second-class status and every bit as unwelcoming as the wealthy. The two groups interact as castes, not as members of a community.

I listened carefully for the pulse of home, for somewhere in this suburbia there had to be an infrastructure of long-time residents who run the businesses and build country clubs, unobtrusively keeping the playground of the rich running smoothly. But the city’s pulse is only a quiet whisper in the cacophony of “flitter and glash.” This is not, in general, a very friendly place. As a non-wealthy stranger in town, I saw few smiles.

Wandering around alone, I sniffed for friendly atmosphere, for the source of those occasional whiffs that suggested a scattered community in hiding. I chased it into Zelda’s, a Palm Springs disco, and quickly remembered why I don’t like discos; I pursued it willy-nilly through the mall and had to content myself with an ice-cream cone. Perhaps I was just imagining things.

The weather was delightful, though, with the typical late-December day slightly cool and sunny, perfect for golf or tennis. And, I gradually found, there are exceptional individuals, many of them, people less interested in forming a community than simply living a life of leisure away from the madness and responsibility of the real world. They are deeply fulfilled.

But I wasn’t, on any level.

A worker with a Santa Ana insulation contractor stole my Aiwa cassette deck one afternoon, plucking it from my lounge chair and spiriting it off to his car while I was indoors answering the phone. His boss promised to “make restitution,” but never did.

I breakfasted regularly at the 19th Hole, enjoying the omelettes and watching the clientele through a cigarette haze. It seemed to be the fashion among construction workers to affect a Chicano accent.

Pressure was building inside me. I was living with someone I had deeply loved for years, in a place generally considered to be a sort of paradise, and the loneliness was crushing. I started riding through dangerous traffic every afternoon, hunting for something, someone, anyone. A girlfriend. A social circle. A pal. A place to shake the loneliness — even a restaurant where I could sit and feel relaxed. No luck. There were a lot of people, even a few vague hints of potential relationships, but never a sense of welcome.

Writing about my adventures in this context seemed like writing a novel, but I threw myself into it (for one man’s playground is another man’s background). In aptly named Palm Desert, my attentions turned inward and thence to the page, and I discovered that I could learn more about the journey by writing about it than by doing it.

But real life grew hazier and hazier. Christmas passed in the bittersweet illusion of home — I joined Remi and her parents in a traditional celebration of presents and fine food. This was my second Christmas in another family, and I was so welcome that it almost hurt. I wanted to escape to the road, but southern California seemed alien. I wanted to stay, but this was not my family. I wanted my family, but I had banished them in a frenzy of restlessness. So what to do?

The road, as always, won the toss.

New Year’s Eve in a bar, the Other Woman only two days away. The waitress brightly arrives to refresh my champagne, then peers through the general haze at the machine before me. “Wow! Is that some kind of typewriter?”

I tilt the display to reflect the Tiffany lamp into her eyes, then flash a grin at her. “It’s a mirror,” I say. “I use it to examine my life.”

“Oh. I thought you were working.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.